[There’s a lot that I like about today’s NBA, and a lot that leaves me scratching my head. One of the pettier head-scratches is that nearly all players today drive to the hoop with a high center of gravity. All they want to do is dance. Gone are the low-center-of-gravity greats who were quick, strong, leaned into their defenders, and couldn’t be stopped from point A to point B. They were like bowling balls rolling down a lane.

One of the best low-center-of-gravity greats was guard Kevin Johnson, best remembered for his years in Phoenix. Here for your reading pleasure is a brief profile of K.J. in his prime. It’s another Fran Blinebury profile, which ran in the 1994-95 Street & Smith’s Pro Basketball annual. Also of note, Blinebury spends most of his wordcount praising KJ’s good deeds off the court. Says a lot about this special kid from Sacramento.]

****

There are plenty of assists in the NBA. The kind that show up every day in the box scores. There are the no-look bounce passes, which produce a fastbreak dunk that Magic Johnson turned into an art form. There are the drive-to-the-hoop, wrap-around-the-defender, and get-it-to-Karl-Malone passes that have put John Stockton on course to become the league’s all-time statistical leader.

Kevin Johnson produces the last type of assist. He can whip a laser beam through traffic and produce an easy layup with the best of them, and he can get the ball to a wide-open teammate for a jump shot. But what Johnson excels at most is a completely different kind of assist. There was the time one of the security guards at his apartment complex was having financial difficulties. So Johnson gave the man $5,000.

There was the time a buddy asked to borrow his car. So he gave him the sporty-looking Mazda to keep. There are the people Johnson meets during his daily life: the sack boys who work at the grocery store, for example, or maybe the clerk behind the counter at the dry cleaners. He buys about a dozen tickets to every Phoenix Suns home game and simply hands them out to the people he comes in contact with every day.

And, there was the old couple—she in a wheelchair, and he always pushing her around downtown Berkeley—whom Johnson used to see when he went to college at Cal. He was constantly stuffing money into their pockets.

Why?

“Because they looked so much and love,” he said.

That’s K.J., an assassin on the basketball court and a Samaritan in the truest sense of the word every place else he walks. After seven years in the NBA, Johnson is as tough on the court as he is kind and generous off it—and that is saying a lot. He is one of only five players in the history of the league to average 20 points and 10 assists in the same season. (The others are Magic, Oscar Robertson, Isiah Thomas, and Nate Archibald.)

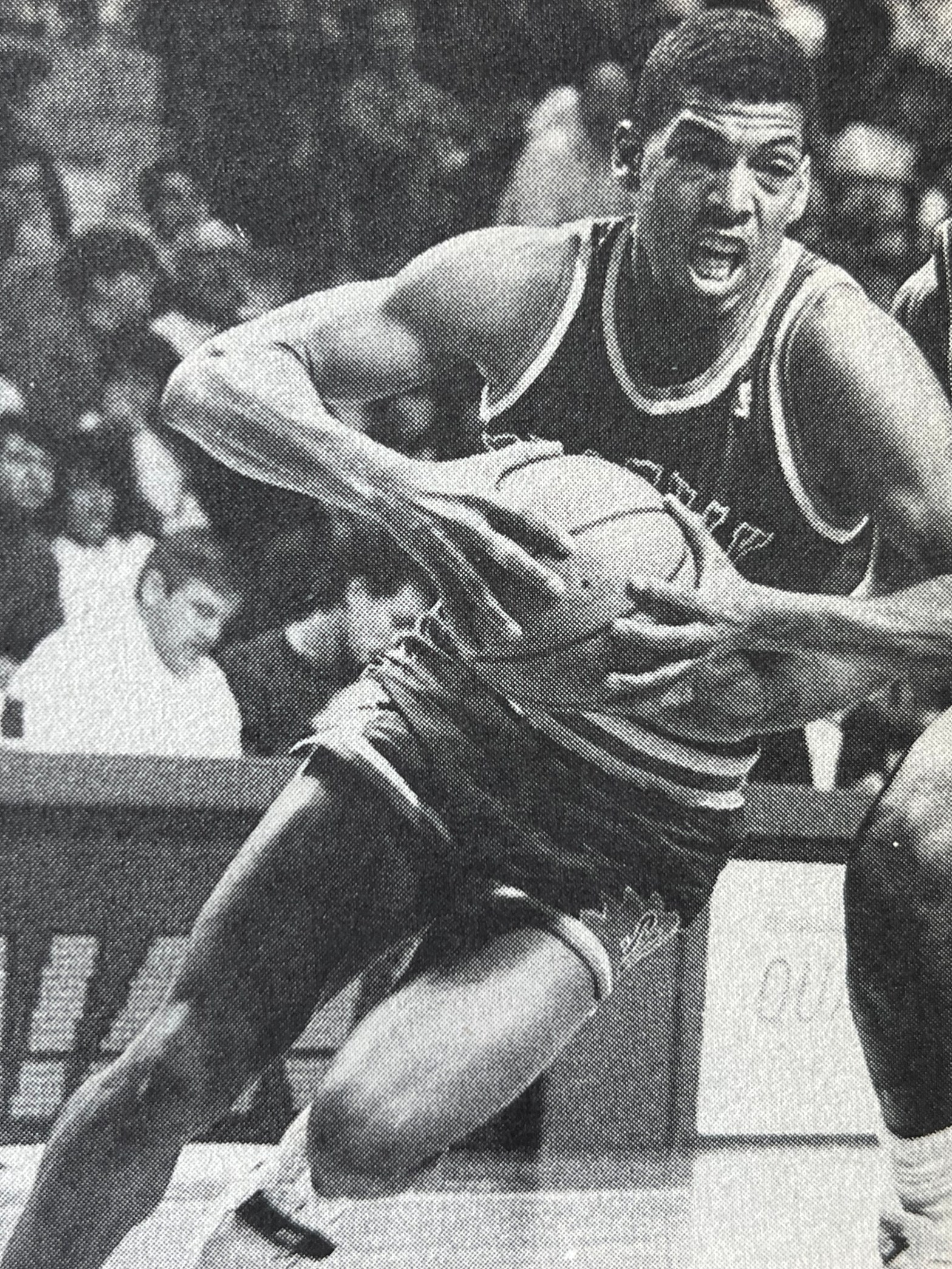

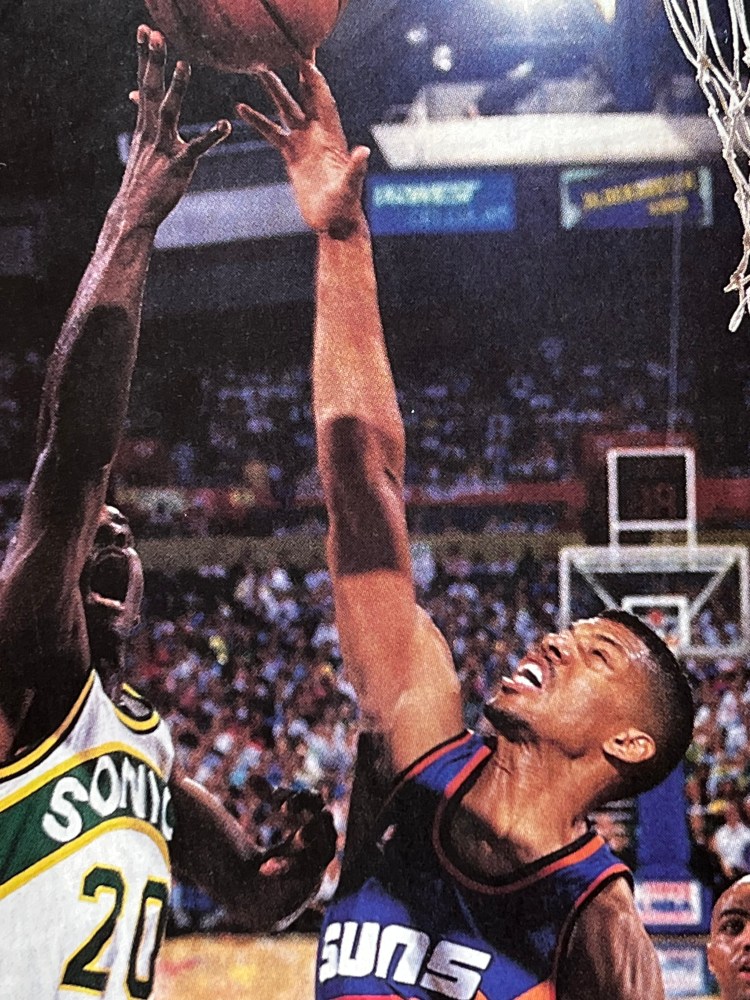

If for the past two seasons Charles Barkley has been the soul of the Phoenix Suns, leading the way with his bombast and his kick-down-the-door style of play, then Johnson has been the heart of the team. He will drive relentlessly to the basket, get hammered to the floor by the giants who patrol the middle on defense. Then he will get right back up and drive to the inside again and again and again. He is as fast as any guard in the league and more stubborn than a mule with an attitude.

During last spring’s Western Conference playoff series with the Houston Rockets, Johnson got up a full head of steam and went up and over Hakeem Olajuwon, the 1994 MVP, and stuffed the ball hard on him. “That was one of the best I’ve ever seen,” Olajuwon said. “I just wish I hadn’t seen it from up so close.”

While Barkley struggled all through the season and labored in the playoff loss to Houston with a bad back, Johnson kept his team afloat for as long as he could simply by bailing water with his perseverance. That would, of course, surprise none of his friends, who know that work is something that Johnson truly enjoys.

Drop by his place for a visit, and you are likely to find him answering the door carrying a bucket and a sponge in his hands. K.J. is an NBA millionaire, but he enjoys doing his own house-cleaning because he wants it done right. He takes pride in the effort.

What Johnson also takes pride in is the realization of his dream to build a center for underprivileged kids in his hometown of Sacramento. St. Hope Academy, located on Martin Luther King Blvd., was opened on King’s birthday in 1992 in the very Oak Park neighborhood that produced Johnson.

“It didn’t take a dream to realize there are many youths who grew up with broken promises,” Johnson said in dedicating the 7,000-square-foot facility that offers young people a home-like environment for study and recreation. “Someone needed to disrupt the vicious cycle. I had a dream that on this lot, once a haven for drug users and transients, would be a place like this. But it took more than a dream to make that possible.”

It took three long years of work and fundraising efforts by Johnson to bring the project to fruition. He paid $40,000 for the land on which St. Hope sits and then went out and raised the $750,000 that was necessary for materials and construction.

“What I hope more than anything else is that people around the country see what takes place at St. Hope,” he said. “I hope people will realize that we have common goals, that regardless of our backgrounds or color or religious beliefs, we can build so many positive things together.”

That’s K.J., always looking to make another assist.