[The chances of a small-college player hearing his name called in this year’s NBA Draft are right up there with Donald Trump nominating a Green Party member to run the Environmental Protection Agency. But in 1971, several NBA general managers were high on seven-foot Elmore Smith, billed as a natural-born rebounding machine and defensive stopper from Kentucky State, a NAIA school. Smith, having played organized basketball for only a few years, was also billed as raw but with a HUGE upside once the right coach polished his skills and let loose his extreme quickness and mobility.

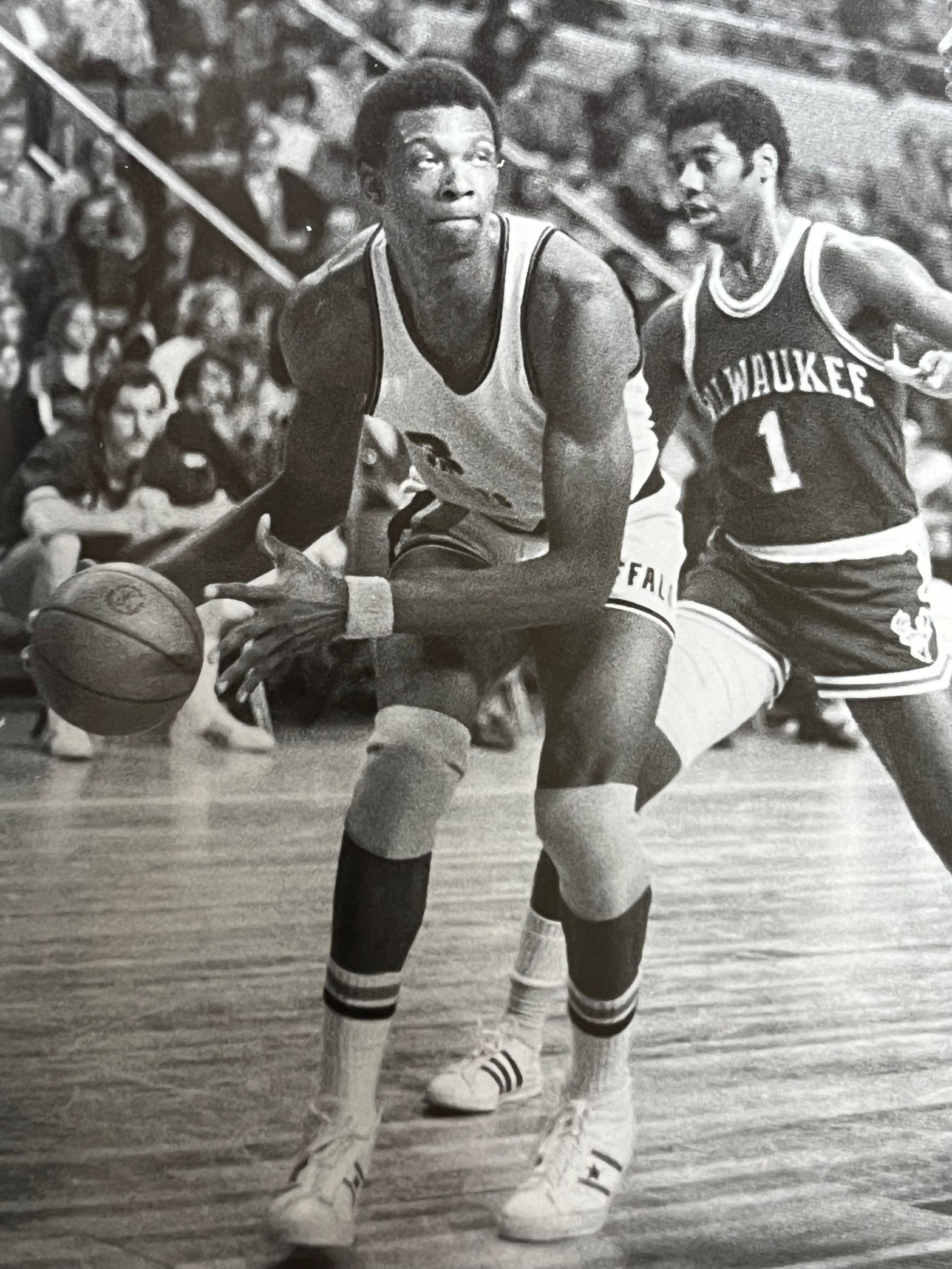

Buffalo GM Eddie Donovan, known for his keen eye for NBA talent, snatched Smith with the third pick of the first round, right after Austin Carr (Cleveland) and Sidney Wicks (Portland). “The biggest thing about Elmore is his lack of experience—but that’s a disguised asset,” Donovan said. “He has no bad habits to unlearn. He’ll conform quickly to our system. But he’s a seven-footer, and that’s something that you can’t teach.”

In Buffalo, Smith would earn the labels “inexperienced” and “Inconsistent,” which would stick like glue to him during his unlucky eight-year NBA career. Unlucky, that is, because the “inconsistent” Smith and his “inexperienced” play never really found the right coach and brand of polish to enhance his game. But Smith’s potential remained for all to see, and it was passed around the league like a pumped-up stock with unrealistic expectations of its yield. Smith, after all, was traded in his young career to replace two of the NBA’s all-time greats: Wilt Chamberlain in Los Angeles and then Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in Milwaukee. It was a standard of greatness that he could never attain or pacify fans bummed by the trades.

By the 1977-78 season, Smith the Project had become Smith the Enigma. Wrote one publication: “Coaches have stopped hoping he’ll be a star and would now just appreciate consistency. Still shows flashes of brilliance when the mood strikes.”

In the first story to follow, Smith is still Buffalo’s rising seven-foot stud, the kid whom Donovan called the “best player” in the 1971 NBA Draft. The story, written by writer Kent Hannon, appeared in the 1972 kid’s book titled Basketball: The New Champions. I rarely pull from kids books, but this one is nicely done, and 50-plus years later, fit for adults to parse.

After the first story, we’ll end with a few newspaper clips on Smith, known as “E” to his teammates, riding the bench in Cleveland near the end of his NBA career.]

****

It should be common knowledge by now that the center is the most-important player in basketball and the single-most critical factor in determining the eventual success or failure of his team. By position and by dimension, he is the closest man to the basket and regardless of what might happen out front between an Oscar Robertson and a Jerry West or in the corner between a Dave DeBusschere and a Rick Barry, all that one-on-one action usually resolves itself somewhere around the metal rim just above the heads of a Nate Thurmond and a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Consequently, smart coaches like Jack Ramsay of the Buffalo Braves try to fill the center position with a man who is the tall enough to enjoy an initial height advantage over nearly all the opposition and leaper enough to maintain the differential when everybody’s bodies go up in the air. The ideal big man should also be agile enough to use his size to score points, and yet rugged enough to take the punishment the job entails and still control the backboards. If a coach is fortunate enough to find this kind of athlete, he is said to possess “the nucleus of a winning team.”

That description certainly fits 7-1, 251-pound Elmore Smith, who paid big dividends on his $2-million contract by averaging 17 points and 15 rebounds for Buffalo. He finished second to Portland’s Sidney Wicks in the NBA’s Rookie of the Year balloting and polled the most votes on the league’s All-Rookie team. Unfortunately, the rest of the quotation does not yet apply to the Braves, who have had to work with three coaches, two owners, two trainers, two controllers, and a couple of publicity men in less than three years. The team has identical 22-60 records and two last-place finishes in the NBA Atlantic Division to show for the resulting confusion, and now it’s up to Ramsay, a fine group of young talent, and the big guy they simply call “E” to change the past in a hurry.

The 1972-73 season is actually only Smith’s fourth year as a regular in basketball. He didn’t play on his high school team in Macon, Georgia, until late in his senior year, and he was anything but a finished product when he enrolled at Kentucky State College in Frankfort. He wasn’t even finished growing.

“I’m from a family of sprouters,” he said. “My father is 6-5, my mother is 5-11, I’ve got two brothers 6-11 and 6-9, and I must have grown from 5-11 to 6-6 after my junior year in high school. I was 6-10 when I graduated.”

As a freshman at Kentucky State, Smith thought all blocked shots constituted goaltending. When he learned differently, he went a little wild to the opposite extreme: “In one game, I blocked 24 shots,” he remembers. “Twelve of them legally and the other 12 goaltending.”

But as a sophomore, “Big E, Bad as You Wanna Be” Smith and Travis “Don’t Be So Mean, Machine” Grant, a 6-8 freshman, teamed up to dominate NAIA basketball.

At first, it was Travis Grant who drew most of the country’s attention. After all, he seldom missed an outside jumper, shooting 62 percent and averaging 27 points per game right out of high school. Smith, meanwhile, made up for Grant’s lapses on defense and averaged 22 points and 23 rebounds, as the Thoroughbreds raced to a 29-3 record, averaged 108 points per game, and defeated Central Washington in the 1970 NAIA championship finals.

Both grew an inch in the next year, and Grant’s totals soared to 69 percent from the field and 35 points per game, including a 75-point evening on which he sank 35 of 50 from the floor. Kentucky State again ran away with the NAIA title, beating Grambling, Elizabeth City, and Eastern Michigan—three very tough teams—the last three days of the tournament. Grant put on a superb scoring performance, as usual, pouring in 82 points in the final two games.

But the strength of Smith, his defense, and the thought of what his general court presence could mean to a young pro franchise with the time to improve, as he improved, had long since tantalized pro scouts. Smith had averaged 27 points and 26 rebounds, shot 62 percent from the field, and scored 44 points in one game, so it was obvious he was no stiff on offense. Nevertheless, it would be his natural affinity for defense that would carry him at first in the pros.

Kentucky State coach Lucias Mitchell seemed to take special pleasure in extolling those virtues, even though he knew Smith would be signing a contract with either the ABA Carolina Cougars or the NBA Braves. “Elmore’s greatest assets are his quickness and defensive timing,” Mitchell said. “He is so mobile that he even goes to the corner to block shots, and Bill Russell was the last man I saw who did that. Russell came to see us last year and said he thought Smith was good enough to play in the pros right then.”

Bill Russell isn’t a man who exaggerates. In Smith’s first six pro games, facing the likes of Jabbar, Dave Cowens, and Wilt Chamberlain, he averaged 14 points, 14 rebounds, and showed the rest of the league he was a body they couldn’t push around long.

After Smith scored 20 points and fouled out guarding Chamberlain in a 123-106 introduction to the game of basketball, NBA and L.A. style, teammate John Hummer said: “The E is cool. He’s got such grace. I have never seen a guy so mature at 22. He just wants to win. First, Wilt grabs the ball, shoves E out of bounds off the edge of the court, and stuffs it. Then E calmly goes down to the other end, gets the ball, runs right at Wilt, slams it in, and calmly and quietly walks away.”

Smith expressed similar feelings, but without a great deal of self-praise. “It’s very hard to psyche me out,” he said, his face as impassive off the court as it is on. “I’ll accept it if you come out and do your thing against me, but I’m not gonna get excited about it.”

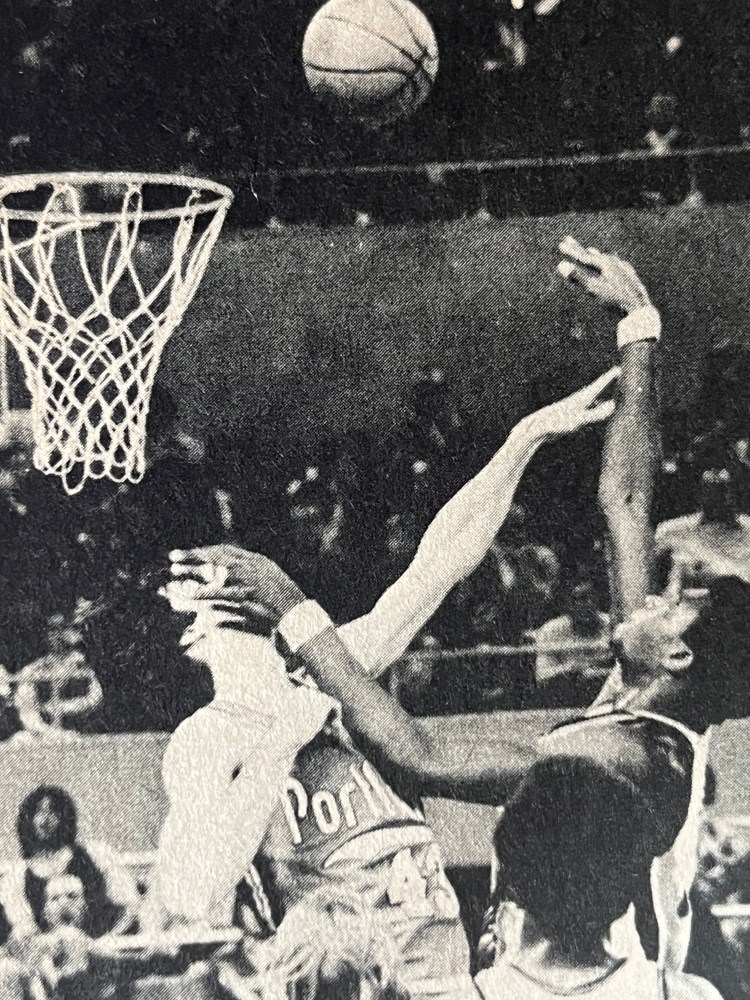

In terms of their record, the Braves were nothing to get excited about in Smith’s first season, 1971-72. But they did move into third place ahead of Philadelphia briefly, and it was Smith who made the event possible. The pivotal game was a 109-100 victory over Portland in which he grabbed 17 rebounds and swatted away 14 shots, four on successive plays when the Trail Blazers started to rally in the third quarter and six more in the fourth quarter as Buffalo pulled away.

Smith’s best effort came late in the season in a 117-115 loss to Boston. Working head-to-head against Cowens, he hit 17 of 27 shots, scored 40 points, and hauled in 15 rebounds. His season average of 15.2 rebounds per game placed Smith in a virtual tie for fifth place in the NBA with Cowens and ahead of the “Big E,” Elvin Hayes of Houston, Bob Lanier of Detroit, and Walt Bellamy of Atlanta, among the league’s good centers.

“If we are going to be a winning team, Elmore has got to be a dominant force on defense.” Ramsay says. “He’s not going to be the primary factor in our offense. We’ll use him more as a relay man, like Wilt at Los Angeles.”

“We’ve got a system now,” Smith replies. “My job is to play defense, hand the ball off better, and help other people score.”

Lest his opponents expect scoring help from the big shot rejecter, it should be emphasized that Elmore Smith was referring only to his Buffalo Braves teammates and excluding all others. It sounds like a good way to begin, and, as Buffalo teammate John Hummer says: “I think we’re gonna win a championship in Buffalo some day.”

[Just over five years after Buffalo’s Eddie Donovan called him “the best player” in the draft, Smith was traded to Cleveland, penciled in as a third-string center and penned in as a big bust. In the next article from January 25, 1977, headlined “The Enigma,” the Cleveland Press’ Burt Graeff lays out how Smith slipped through the NBA system without finding the right team and fit.

A quick point. Smith broke in with two Hall-of-Fame coaches: Jack Ramsay (Buffalo) and Bill Sharman (Los Angeles). The argument could be made that Smith was just a bad student. But I don’t think that’s right. Dr. Jack, in his eyes, was the great stage director who needed finished parts to fit into his winning show. Smith wasn’t finished, and Ramsay, to his credit, recognized that the high-scoring Bob McAdoo was a tantalizing option for him at center. That made Smith expendable. In Los Angeles, Sharman was consumed with a personal crisis: His wife (and soulmate) was dying of cancer. In addition to coaching a declining Lakers team, Sharman was caring for his wife. He had nothing left emotionally for Smith.]

There’s something about being peddled around from one basketball team to four basketball teams in five-and-a-half years that turns a vibrant youngster of 22 into a very skeptical adult of 27.

Elmore Smith was a vibrant youngster of 22 in 1971 when he left Kentucky State following his junior year to join the NBA’s Buffalo Braves. Today, at age 27, Elmore Smith’s voice rings with skepticism. The 7-foot, 250-pounder is now playing for the Cleveland Cavaliers, his fourth team in five-and-a-half years.

“Everything is fine when you first come into a new situation,” he says, his voice trailing off.

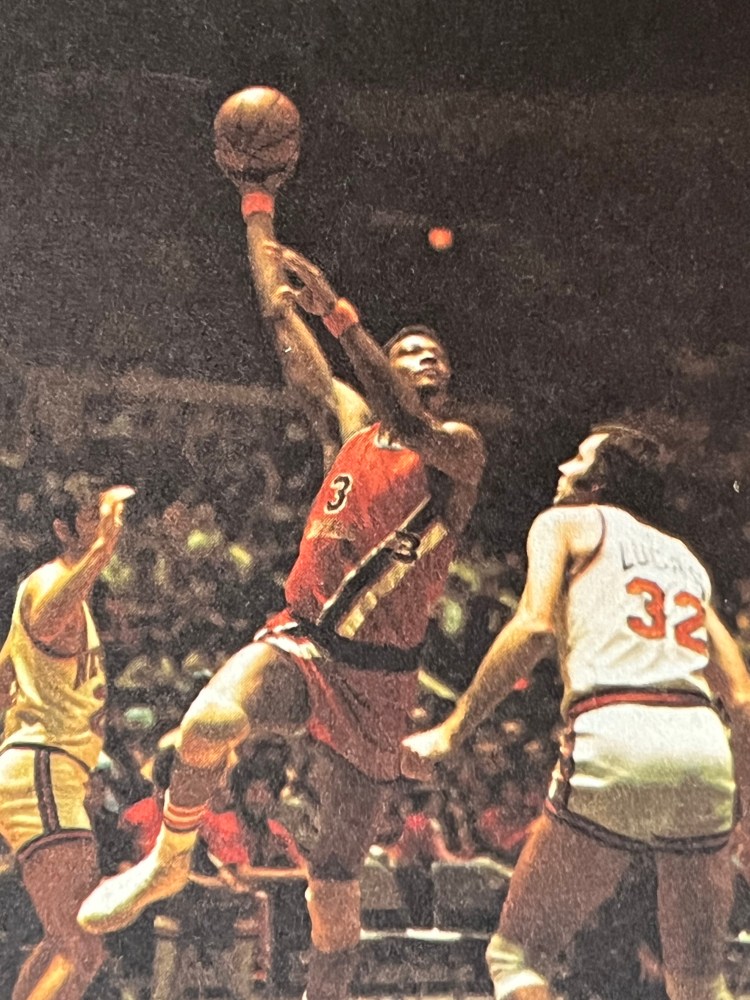

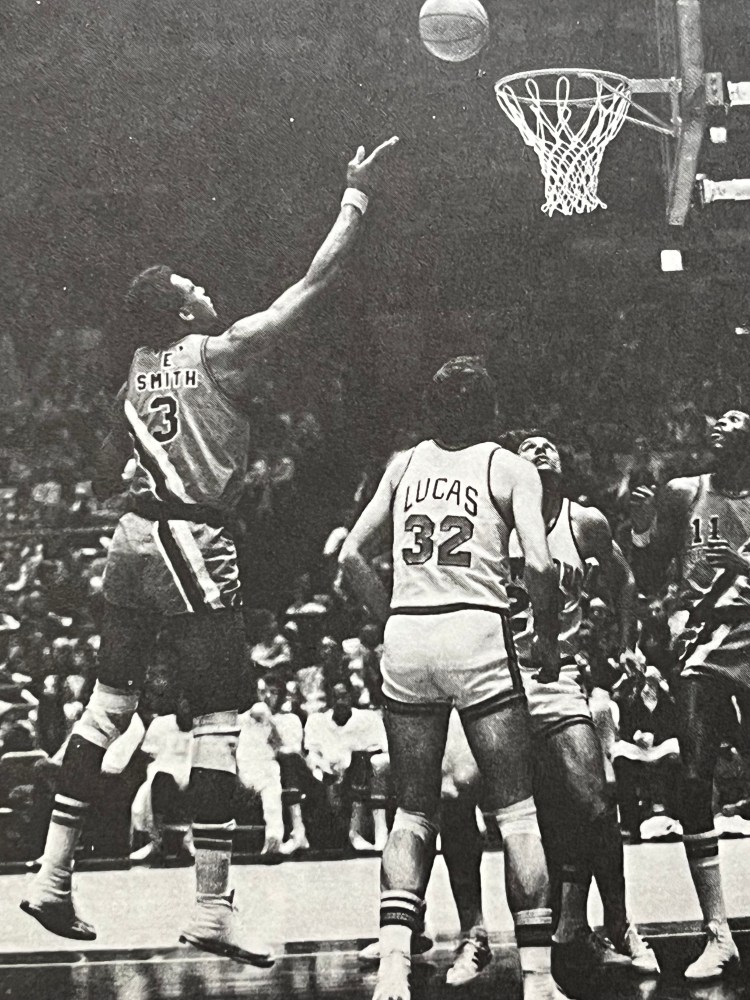

Everything seemed to be fine at first for Elmore Smith in Buffalo. Then it was Los Angeles. Then it was Milwaukee. Now it is Cleveland. Elmore Smith has been an enigma no matter what the team. At Buffalo, he was to turn a young franchise into an instant contender. At Los Angeles, he was to follow Wilt Chamberlain. At Milwaukee it was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

There was something else that followed everywhere. “Throughout my career,” he said after a workout yesterday at the Cleveland Coliseum. “I have always been told I had a lot of talent. I have never been taught how to use it, though. Bill Fitch has promised that he would teach me how to use all of it.”

There is a simple explanation why Elmore Smith has not progressed as rapidly as perhaps people feel he should have. He did not begin playing the game seriously until his senior year at Ballard-Hudson High School in Macon, Georgia.

Smith’s initial taste of college basketball was not good. He played four games for a small Texas school, Wiley College. “They told me all I could do was play defense,” he says. “I was not to get involved in the offense at all. We won all four of those games. I couldn’t stand it, though. I left.” The team didn’t win a game the rest of the year.

Smith followed that by enrolling at Kentucky State. His career blossomed there under the tutelage of Lucias Mitchell. “He was the one who taught me the fundamentals,” says Smith.

With Elmore Smith in the pivot, Kentucky State won two-straight NAIA championships. Then, following his junior year came the offers to sign with the NBA as a hardship case. “I didn’t want to go to the pros,” says Smith. “I was playing for a great team at Kentucky State, the guys were close and the environment was nice.”

Money, like financial security for the rest of his life, forced Smith to leave Kentucky State for the Buffalo Braves. “I’ve never had the fun in the pros that I did in college,” Smith now admits. “Oh yeah, everybody says we’ve got it locked up with the big money we make. Believe me, though, I wonder sometimes if it is all worth it.”

Perhaps the biggest rap against Smith, who is a Bible student, has been that he is not aggressive enough on the court. “I think I am as rough as anyone,” he counters. “I can do whatever people want me to do without going wild out there.”

Smith admits he has been stung by what coaches have said about him after he has been traded away. “In several cases,” he says, “I had good relationships until I left. Then a lot of bad things seem to come out. I’ve tried not to let it bother me, though. I’m getting paid to play basketball, and I just don’t have time to worry about those things anymore.”

[As the 1976-77 season wore on with its low expectations of him, Smith went high. This article, headlined “Intimidator” and written (like the one above) by Burt Graeff, explains why Smith wasn’t a bust in Cleveland. The story ran on April 5, 1977 in the Cleveland Press.]

Ten weeks ago, Elmore Smith joined the Cleveland Cavaliers, and coach Bill Fitch figured he had a real piece of work on his hands. Elmore Smith’s name was synonymous with all sorts of labels. It was said he couldn’t take criticism, that he wouldn’t play hurt, that he lacked competitiveness, that he wasn’t smart, and that he was a loner.

Other than the above, Elmore Smith was deemed a bona fide NBA center.

Ten weeks hence, Bill Fitch is forced to pinch himself on occasion and wonder just who the guy is backing up Jim Chones at the center spot. Elmore Smith, maligned for two seasons in Buffalo, maligned for two seasons in Los Angeles, and maligned for a season-and-a-half in Milwaukee, is anything but maligned in Cleveland.

The 7-foot, 250-pounder has, in fact, done a remarkable job of conducting a Nate Thurmond imitation of intimidation, and one has to wonder just whether or not the Cavaliers would be playoff-bound today were it not for this former Kentucky State star.

Smith, along with Gary Brokaw, was obtained from Milwaukee for Rowland Garrett and two first-round draft picks on January 14, 1977. Three weeks later, on February 8, Nate Thurmond went down with an injury that eventually led to knee surgery.

The trade made Fitch look like something of a combined genius and soothsayer. He explains why he made the trade for Smith this way . . . “I’m a belt-and-suspenders type person, and this is the kind of business where you have to keep looking for the hazards that might come up. I hate, however, to think what we would have had to do without Elmore and with the trading deadline passed.”

Smith, 27, has played three different roles in his 10 weeks here. He was the third-string center when Thurmond was healthy, he was the first-string center when Chones was slumping, and now he is the second-string center. Says Fitch: “He has been highly instrumental in a lot of our victories.

Like in Sunday night’s 113-107 playoff clincher over the Kansas City Kings for instance. Smith, in that one, took over in the final period when he continually pulled down rebound after rebound and served as The Intimidator, as the Cavaliers caught and passed the feisty Kings. “Elmore has got a lot of work to do yet,” says Fitch, “but it’s the type of work that can only be done in a training camp situation. I don’t feel he’s anywhere as good as he can be, but I do think he’s actually improved in the time he’s been here.”

Smith has averaged 19 minutes a game for the Cavaliers, scoring 9 points, pulling down 6.7 rebounds, and shooting 52 percent from the field. That’s made Fitch genuinely surprised at the Elmore Smith he’s got versus the Elmore Smith he was reputedly getting.

“First of all,” said Fitch, “I was told you couldn’t holler at Elmore . . . that he wouldn’t take to that sort of criticism. Well, I have hollered at him, but I think he knows me good enough to realize I am criticizing him as a basketball player.

“Elmore was also pegged as being an introvert . . . a loner. From what I’ve seen, he’s got a tremendous personality, he gets along great with the other players, and he is one of the most congenial people we have. Fitch likens Smith’s career to that of Chones, who left Marquette to join the New York Nets of the ABA for big money.

Fitch continued: “Too much was expected of Elmore, and he was moved around like a stick of furniture. He started reading all sorts of things about himself that simply weren’t true, and I think this caused him to withdraw at times. He is not a sit-in-the-corner type.”

“The big thing with him is that he was never anywhere long enough to know what people expected of him,” said Fitch.

It is beginning to sound is though Elmore Smith won’t be having that problem in Cleveland.