[The Los Angeles Lakers, after many failed attempts, won their first NBA title in 1972. For the Lakers, it was a magical season that would live on in NBA lore mainly for the team’s 33-game regular-season winning streak, but also, on a more personal note, Jerry West (“The Logo”) finally got the championship that he’d obsessed over since entering the league in 1960.

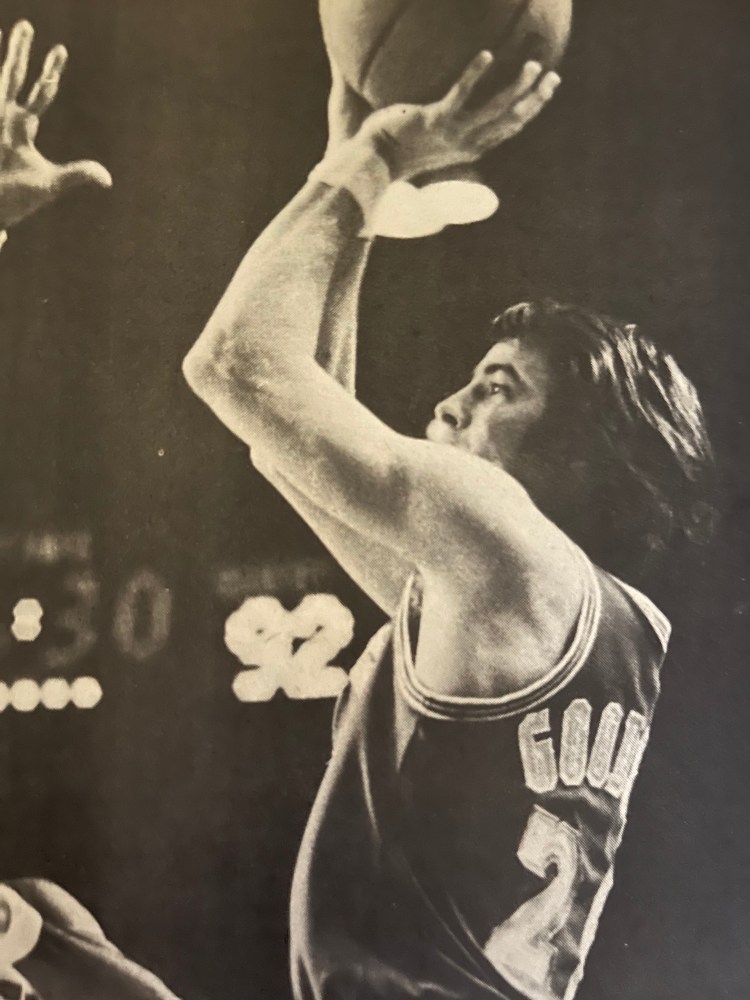

Sometimes overlooked are the personal notes of West’s teammates. A good example is Gail Goodrich, West’s 6-1 backcourt mate, who had a phenomenal season. Goodrich not only outscored West that season by a decimal point, he came up huge in the championship series against the New York Knicks. In fact, it’s impossible for me to recall the 1972 Lakers without pulling up a mental image of the southpaw Goodrich either dropping in a soft, mid-range jumper or busting full steam to the basket.

If you want to recall or learn more about how good Goodrich, a.k.a., Stumpy, was during that magical Laker season, then read on. I’ve strung together three stories from three of the era’s better informed NBA writers. The first comes from the typewriter of Phil Elderkin, who wrote for the Christian Science Monitor and, then more noticeably, The Sporting News. Elderkin offers a nice overview of the arch of Goodrich’s NBA career and the reasons for his second chance in Lakerland. Elderkin’s story appeared in the Christian Science Monitor in April 1972.]

****

The race to make it big in pro basketball is always for the swift, the talented, and the tall. If you don’t have two of the three, forget it.

When the Los Angeles Lakers drafted guard Gail Goodrich from UCLA in 1965, rival scouts figured he qualified for only one count—speed. His future dismissed as casually as a .220 hitter being worked on by a Cy Young Award-winning pitcher. One day in training camp and Goodrich would be packing his socks as well as his lunch. Oh, he had talent all right, but it was what the pros like to call college-oriented talent.

Elgin Baylor took one look at Gail’s 6-feet-1 frame and called him Stumpy. This kid may have been an All-American shooter in college, everybody said, but those pro defenses would never let him get his shot off. Besides, how often was he going to see the ball anyway with Jerry West playing next to him and Baylor in front of him?

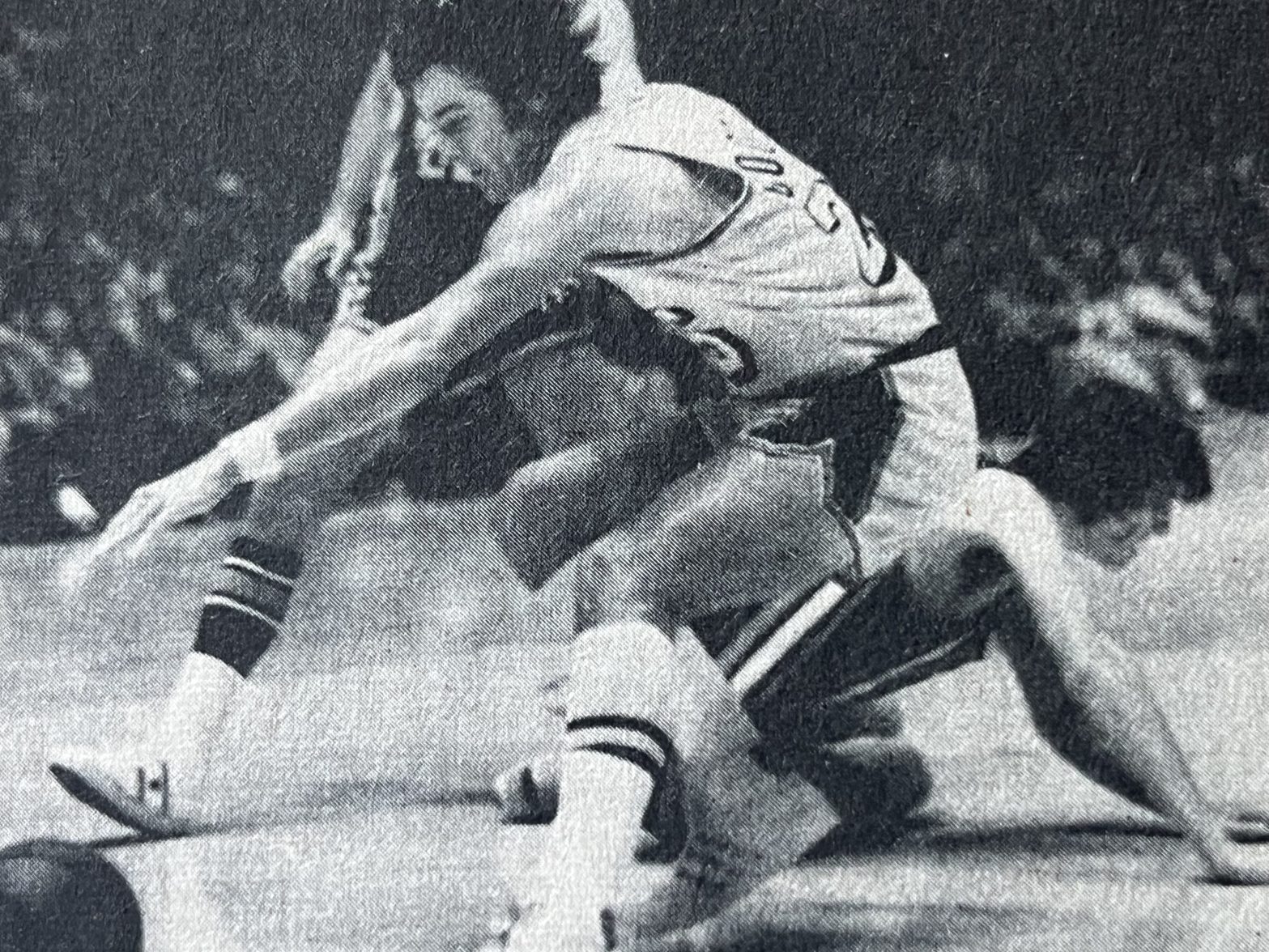

As it turned out, not much. But on the few occasions when Goodrich did get to play, he scored. Nobody was quite sure at first how he was getting his points, because he seemed to be scoring as often on layups as jump shots.

But if you watched him closely enough, you could see him fake the big man to one side as he came down the lane, shift the ball from one hand to the other on inside moves, and score. In fact, he even embarrassed Boston’s Bill Russell a couple of times.

Still, the Lakers never quite appreciated him. They thought other teams exploited his height a little too often on defense, and they were also suspect about a man who never had more than 210 assists in one year.

Goodrich was getting a trifle anxious, too. He not only wanted to play more, he wanted to start. Finally, he asked the Lakers to trade him. They didn’t exactly rush to deal him away, but they did expose him to the NBA’s 1968 expansion draft.

The Phoenix Suns, badly in need of established names and proven shooters, grabbed him. It was an ideal situation for Gail—he ran the Suns’ offense, mixed in a little playmaking with his scoring, and averaged about 24 points a game.

Meanwhile, back in Los Angeles, the man who was pretty much acknowledged as the best of the game’s top shooting guards (Jerry West) averaged only one point higher. There were not only second thoughts in the Lakers’ front office now about letting Goodrich go to Phoenix, but also third and fourth thoughts.

Released from the situation which forced him to caddy for Baylor and West, Gail began to establish an all-star reputation of his own. They still called him Stumpy, only people now smiled when they said it.

The fact is Goodrich should have been set for years in Phoenix, but two things happened which pointed him back in the direction of the West Coast. First, the Suns signed Connie Hawkins, the best player in the rival American Basketball Association, but a gentleman who needed the ball as much as Baylor. And the price Phoenix paid to get Hawkins also included possession of the basketball. Gail was back to his caddy role again.

The Suns also drafted a center that year—Neal Walk—who proved to be a huge disappointment. When Walk couldn’t run, Phoenix decided to go into the marketplace at the end of the season and get a pivot man who could. On May 20, 1970, two years after he became a member of the Suns, the Stump was traded back to the Los Angeles Lakers for Mel Counts, a seven-foot redwood.

Gail wasn’t any taller than when the Lakers first drafted him, but he was smarter. West averaged 24.8 points for the Lakers this year, and Goodrich (fourth best in the league) did 25.9. Okay, so he only beat Jerry by a decimal point But anytime anybody beats Mr. West at anything, it comes under the heading of a major achievement.

[Up next is Laker beat reporter Doug Ives. He may have written for smaller circulation newspapers in Long Beach, but his prose were just as fine and polished as his competitors at the high-profile L.A.Times. Here is Ives’ piece on Goodrich playing third fiddle to West and Wilt Chamberlain during the 1972 championship series. The story ran in the Long Beach Independent on May 5, 1972. Take it away, Doug.]

There were so few people around his dressing stall that it looked as if attendance was by invitation only. Or maybe someone detected an outbreak of measles.

The scene was the Lakers’ locker room after the third game of the NBA playoffs, and the man getting the cold shoulder was Gail Goodrich, whose contribution to the victory was 25 points, including nine in the decisive third quarter.

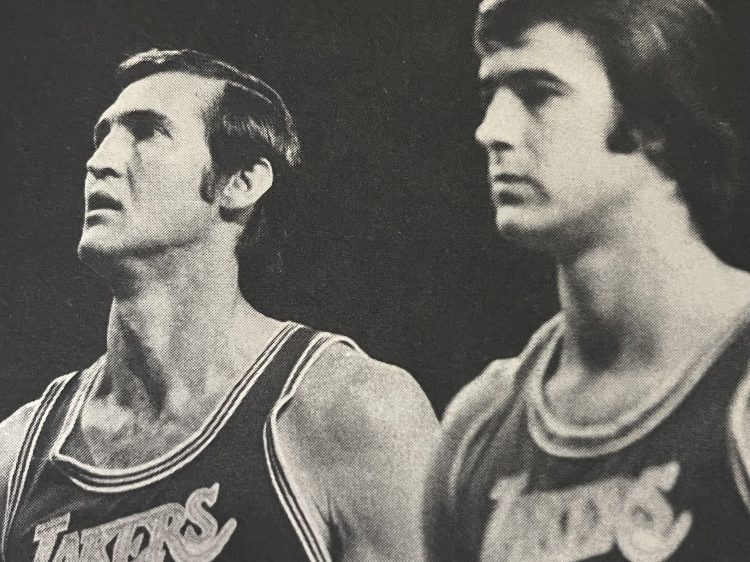

Writers were stacked five deep trying to hear pearls of wisdom from Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain. Ten feet away was Goodrich, alone except for a mound of tape that he had ripped from his tender ankles.

Is Goodrich the most ignored superstar in basketball? Doesn’t the fact that he led the team in scoring (25.9) during the regular season and is doing the same in the playoffs, count for something? And how about the first-team all-star berth that he earned?

It’s enough to cause any self-respecting athlete to kick the water cooler, all this unfair lack of notoriety. Except Goodrich, that is. He doesn’t care—really he doesn’t. “Heck, I don’t have anything to say,” the littlest Laker maintains. “And besides, I don’t want to get into all this analyzing stuff and this talk of matchups. That’s a bunch of nonsense, mostly. I just want to go out and play ball.”

But doesn’t your ego call for a fair share of the glory?

“I get my share,” he asserts, “but it comes from the players, not the press. I don’t talk a lot because I don’t want to be misinterpreted or misquoted . . . I don’t want anything I say taken out of context.”

If you think that is a rap on the press, Goodrich maintains, it isn’t. He feels it’s quite natural to be interpreted many ways if you answer hundreds of questions. Just ask West or Chamberlain. They say they have read things they haven’t said, then wonder perhaps if they did make those remarks somewhere along the way.

Goodrich knows he lacks color, but he doesn’t think it will affect him financially. He earns more than $100,000 a year, and he has the respect of his teammates. What else does he need?

Phoniness is not Gail’s bag. He doesn’t play the “put on” game, he doesn’t seek sympathy for a nagging groin injury, and he doesn’t criticize his teammates. The former UCLA All-America, who just turned 29, is even embarrassed by acquiring “fame” he didn’t earn.

For example, Esquire Magazine has chosen him as one of the top 10 best-dressed athletes in sport. But he knows very well that Pat Riley is far more suave. “I had to go out and buy some clothes so they could take the proper picture,” Gail says. “It’s ridiculous.”

For a man who isn’t talkative, Goodrich was turned on now. But he was trapped in a whirlpool bath at Bishop Ford High in Brooklyn, where the Lakers practiced Thursday, and idle conversation seemed in order.

The soon-to-be papa (in October) was saying how this season was his best ever and how it all started when he underwent a running program with UCLA track coach Jim Bush. “[Coach] Joe Mullaney used to ride me all the time about my lack of speed,” Gail recalls. “Then I met Nick Skorich, the Cleveland Browns’ coach while I was on a fishing trip, and he told me some interesting things about getting in shape.

“I started running 10 minutes a day, then 15, then up to 25. My stamina increased, and, all of a sudden, I wasn’t nearly as slow as everyone thought I was.”

If you ask an opponent, he would probably say Gail is as quick as a tiger and twice as deadly. He has more moves than a belly dancer, the confidence of a card shark.

K.C. Jones, the Lakers’ assistant coach who once was rated as the best defender in the NBA, said he would hate to guard the little southpaw. “His moves are fantastic, and he knows how to set you up, get you out of position.”

Defense is supposed to be Gail’s shortcoming, but Jones says, “He’s getting better all the time. He’s thinking more about what to do . . . he’s learning tendencies of other players . . . and he knows he has to play well or let his teammates down.”

Goodrich says his blossoming into a superstar is due to many things, not the least of which is the confidence that coach Bill Sharman has instilled in him. “He tells me to shoot when I feel like it,” Gail states. “He knows what I can do and what I can’t.”

If the Lakers win the championship, Goodrich says most of the credit should go to the coach. “I liked Mullaney last year, but Sharman is better able to communicate with the players. He has better discipline and is able to get us to do what he wants.”

In one way, Sharman, and Goodrich have a lot in common. When Sharman played for the Celtics, he led them in scoring for four-consecutive years, was the top percentage shooter, and always guarded the best player on the other team.

“But do you know who got all the notoriety?” Sharman laughs. “It was Cousy and Russell. They were the colorful ones. Me, I got some attention from my relatives, but that was about all.”

Yes, coach, Goodrich knows exactly how it is.

[Last but not least is this longer magazine article from Al Goldfarb, who got his start in sports journalism at Newsday. Here, Goldfarb decided to quit ignoring Goodrich. Goldfarb looks back on Stumpy’s big year and closes the loop on the Lakers’ historic season in Pro Basketball Illustrated, 1972-73. Goldfarb, by the way, moved in 1973 to the San Francisco Bay Area to write for the Hearst newspaper chain. Once there, Goldfarb discovered fine wine and fine dining. It wasn’t long before he quit jump shots to report on California wines. So, here’s a toast to Goldfarb and his former career covering sports.]

His teammates call him, “Stumpy.” Laker fans go wild over their little southpaw backcourt ace. And Gail Goodrich even made believers out of the most ardent New York fans after what he did to the Knicks in the NBA championship series.

Coach Bill Sharman says Goodrich played like a superstar for the Lakers last year. “He’s a big reason we got off to such a great start,” says Sharman.

The 1971-72 season is one Laker fans will long remember as the year their team won its first NBA championship since it moved to Los Angeles in 1960. It was an incredible year. Not only did the Lakers capture that elusive crown, they also won a record 69 games and compiled a 33-game win streak—the longest in major-league sports history.

The littlest Laker of them all played a mighty big role in all of this. At 29, the 6-1 former UCLA star enjoyed his best pro season, finishing as the fifth-leading scorer in the NBA. Gail averaged 25.9 points a game, a mark surpassed by only Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Nate Archibald, John Havlicek, and Spencer Haywood. He also finished third among free-throw shooters in the league with an 85 percent average.

It’s a mistake to think Goodrich has suddenly emerged on the scene as a top NBA guard. Before the Lakers traded Mel Counts to Phoenix for Goodrich in 1970. Gail made the all-star team while a member of the Suns. Goodrich was drafted by the Lakers on the first round in 1965, playing three seasons with Los Angeles before he went to Phoenix in the expansion draft.

But last year was a very special one for the boyish-looking Laker ace. Together with Jerry West, they formed their own gang that could shoot straight and averaged 50 points a night between them. When Jerry’s shooting was off, the Lakers could count on Gail to carry the attack with his accurate left-handed jumper or twisting, driving layups.

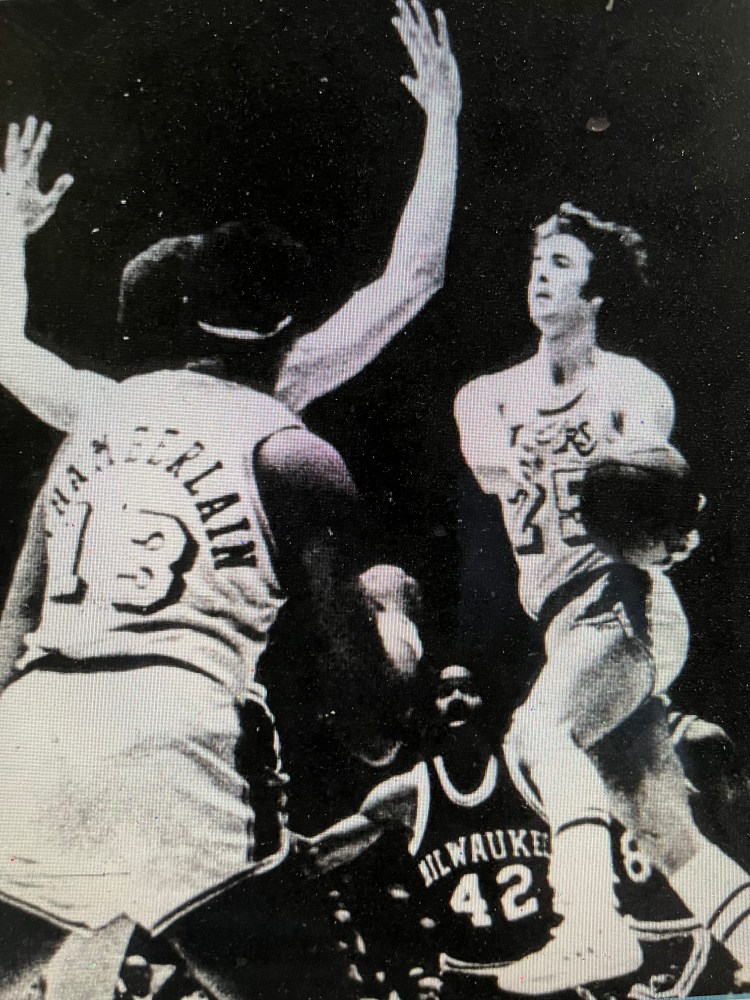

“Stumpy” demonstrated this ability in the second playoff game with the Knicks at the Forum. New York stunned the Lakers by taking the opening game of the final series on the hot shooting of Jerry Lucas, 114-92. It was obvious the Lakers had suffered a mental letdown in the opener after they had disposed of the defending titlist Milwaukee in six games. As Gail says, the defeat “woke us up.”

The second game, then, was a “must” win for L.A. West, in a shooting slump from the outside, could hit only 6 of 21 for 15 points, so Goodrich stepped in to provide the needed firepower. He connected on 14 of 18 shots and 3 of 4 at the line for 31 points to lead the Laker win (along with Wilt Chamberlain who was devastating with 23 points and 24 rebounds).

The Lakers ripped the Knicks, 106-92, and went on to wrap it up in five games. In the first period, Gail matched Walt Frazier’s 6-for-6 shooting and 14 points with 7-for-9. During one stretch, the hustling Laker guard hit a jumper, fed Chamberlain for a stuff shot, stole the ball from Earl Monroe for a layup, and then dropped a 20-footer—all this inside of two minutes.

When the Knicks closed to 10 points with four minutes left, reserve LeRoy Ellis and Goodrich blunted the rally with clutch baskets. Typical of Goodrich, he shrugged off his 31-point performance and his driving, slashing game that bothered the taller Monroe. “Individual matchups don’t really mean that much in a game like this,” said Gail. “It’s a team game—not a game of individuals. I really don’t think the matchups are that important.”

The Lakers were really pleased with Gail’s improvement last year at both ends of the court. “I knew that Gail was a great scorer, but I’m most pleased with his improvements on defense,” said Sharman. “I think the fact that a player tries to improve himself is one sign of a superstar, and Gail is always working hard to improve.”

Goodrich credits Sharman and assistant coach K.C. Jones, who has since left the post, with being important factors in his play last season. “Sharman’s running offense is really the type of game like best,” says Gail. “I like to move without the ball, and when you run it, it is easier to get open for a shot.”

Gail also says that K.C. had helped him on defense. “Jones has helped me in pointing out on defense you have to pick up the opposing guards further out, even in the backcourt. This way they can’t get inside against me.

“Defense was the weakest part of my game,” continued Gail. “He talked to me stressing the importance of it, and I got to thinking defense is my mental approach.

“Defense is a team game, and a guy my size has to have some help. Wilt is a great player for me to play with because I can play some guys a little tighter, knowing he’s there to help me out. He takes away the driving ability of a lot of players.”

One of Gail’s best defensive games came during the playoff series with Milwaukee. Gail was tenacious on defense and frustrated the Bucks’ Lucius Allen, who didn’t get his first field goal until the second half.

After the Lakers defeated the Bucks, 115-90, to take a 3-2 edge in the playoffs, Sharman lauded his backcourt star, who finished with 22 points. “That’s the best defensive game I’ve ever seen. Gail play,” he said.

In the Lakers’ 107-96 win over the Knicks in New York, Goodrich hit 25 points and also had Monroe talking to himself by shutting him off at the other end of the court.

Conditioning played a major role in his success last year, although it started out somewhat as a joke. After a conversation with Cleveland Browns football coach Nick Skorich. Gail was convinced there was no reason why basketball players shouldn’t prepare for the season, as do football players.

“I went to UCLA track coach Jim Bush,” says Goodrich, “ and he mapped out a training program for me consisting of distance running. I realized I’d be cheating myself if I didn’t get myself in the best possible shape before the season. Most athletes fail to realize that the first thing to go are the legs,” he continued.

“I was in excellent shape the entire year. I never tired, and the long season never bothered me. I also had no injuries, which was unusual, since in the past, I had sprained ankles or pulled hamstrings. Running barefooted must have strengthened my ankles.”

While the preseason training proved beneficial, Goodrich admits he hated every minute of the running. “It was boring, but it helped me prepare physically and mentally for the season.

****

As a professional, Gail believes he must get better every year. “We get better by experience, and this plays a part in development as a pro. Super confidence is important. It borders on being cocky, but you must believe in yourself and have confidence in yourself as a player. Sharman gave me great confidence in my style of play. He told me I could shoot whenever I had a good shot. All of these things, I think, helped me have the kind of year I had.”

Goodrich dismisses any talk of his being a superstar with the Lakers. “Sure, I always want to be the best,” he says. “I don’t know what super status points up, because basketball is a team game. The important thing is to play your best and to win the game.

“Too much importance is placed on superstars. I guess the league grew up promoting its stars to attract fans. Now I think the team aspect of defense has forced it to change. There are so many good players today.”

Winning the title won’t change things for the Lakers this season, explains Goodrich. “Sure, the championship was the greatest moment in our lives and our careers,” he says. “Except for Wilt, nobody on the club had ever played on a pro championship team. But you can’t live off past performances. You’re no better than your next game. It’s a whole new season this year.”

Gail believes the Lakers will be a hungry team this year, even if it has won that long-sought championship. “Sharman has a lot to do with it. He won’t let us get complacent,” says Gail. “Besides, if you don’t get better, you get beat. As I look back at our 69-13 record last year, there are a half-dozen games we could have won and, by the same token, there were some we were lucky to win.

“It’s hard to say if anybody will break our 33-game win streak. That’s a fantastic sports record. It may stand for some time; then again, it might not. We’ll be tough this year again, especially with Keith Erickson back.”

The Laker star enjoyed every minute of the championship season, especially during the win streak. “The pressure of winning didn’t bother me,” he says, “because I don’t think about pressure. Basketball is a game of habits and reaction, and concentration is important.

“It’s fun to win. Before each game, we knew what we’d have to do to win and to adjust to each team. The win streak really built our confidence. We all knew that sooner or later we’d explode. Psychologically, we knew it, and so did our opponents. We all played with confidence.”

Confidence in his own shooting ability was a factor in Gail’s teaming with Wilt to blow down the Knicks in the fifth and final playoff game at the Forum. In the 114-100 victory, Gail broke out of a third period slump in which he was 0-8 at one time and wound up with 25 points, his season average.

With the Lakers protecting an 85-83 lead with 10 minutes to play, Goodrich started the championship run with a drive-in shot, then Wilt hit, Happy Hairston scored a layup, and Jim McMillan got a pair of free throws. The Knicks’ outside shooting deserted them, and they were scoreless in seven attempts while the Lakers pulled away to the title.

Now that the Lakers have found the formula for success they don’t intend to sit back and rest on their laurels. “We’ve got a new goal this year,” Gail says, “to repeat as NBA champions.”