[Harkening back to the “perfect season” of the 1972-73 world-champion Los Angeles Lakers usually means revisiting Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West, and Gail Goodrich. But three stars don’t a championship team make. Often overlooked is the glitter of Jim McMillian, then a second-year pro who took over like an old pro for the badly ailing-turned-retired Elgin Baylor.

What follows is a classy profile of McMillian early in his rookie campaign. The story, penned by the award-winning Peter Bonventre, is a time-machine piece the brings the early 1970s back to life. The profile ran in the Los Angeles Times Magazine on November 15, 1970. Once Bonventre finishes with the rookie, we’ll jump to a profile of McMillian as an NBA sophomore that recaps the Lakers’ “perfect season.” Enjoy!]

****

His long, bony fingers choked the handle of his red-plaid suitcase, and he eased his thick-ribbed body out of the cab. Just then, a cool June breeze whipped through Los Angeles International Airport. A warm smile played on Jim McMillian’s lips and his eyes sparkled as he surveyed the cloudless morning sky. “This is a beautiful town,” he said softly. “Who needs New York? I’ll be back here soon, and I intend to stay awhile.”

Jim McMillian was going home. He had just spent a week at the Los Angeles Lakers’ rookie camp, where coach Joe Mullaney drilled his bright-eyed recruits in the business of professional basketball. But there was still much to learn. McMillian was the Lakers’ top draft choice last spring out of Columbia University, and first round draft picks aren’t supposed to make themselves scarce. Their coaches get lonely.

So, a little less than two weeks later, McMillian flew back to the coast, and Mullaney supervised his workouts more intensely during the Lakers’ development program at Pepperdine College, along with other Laker hopefuls. A number of established professionals, including Laker Rick Roberson, also participated in the daily two-hour scrimmage, loosening up off-season muscles and honing competitive skills.

McMillian has had to scramble and hustle throughout his 22 years. Life in a New York City ghetto presented precious few options to a fatherless Black emigre from the South. When it did, the choices were pitifully limited. Basketball was frequently the clearest alternative to oppressive boredom, drugs, or crime. It was, he says, the soul of his turbulent, often frustrating existence. McMillian mused, “If I didn’t have basketball, I don’t know what I would’ve done.”

Baseball is fundamentally bucolic for kids who live near rambling pastures a million miles away; football is a violent, elaborate spectacle played by clumsy, oversized oafs, who have little appreciation of the hours of toil needed to perfect the ”moves” that give modern basketball its special grace and style.

So it’s been that many of the greatest players have often been the hungry products of inner-city living and playground battling. And perhaps no city has a more valid claim to adopt “hoops” as its own game than does New York. “Just riding a subway takes more moves than I could ever teach a kid,” says South Carolina coach Frank McGuire, whose nationally ranked Gamecocks boasted four starting New Yorkers last season. “A boy’s got to be quick just to survive crossing a New York street. A New York cabdriver isn’t happy unless he tags at least one pedestrian a day.”

No cabdriver ever got a clear shot at McMillian, who says he can sidestep a moving cab while looking the other way. Moreover, he dodged the pitfalls of ghetto life long enough and well enough to put it all together at Columbia. A hefty, rabbit-quick forward at 6-feet-5 and 225 pounds, he impressed the Lakers with his superb body control, keen eyesight from the corners, and durability. In the inner-city vernacular, McMillian has the good “moves.” He commands a startling variety of feinting, twisting body movements that, in an instant, can leave a defender flat-footed—and McMillian free to score an easy, three-step layup.

Not too many Columbia men spent their first eight grades in a segregated grammar school in North Carolina. Reared in the dusty, backwater town of Raeford, McMillian relishes some pleasant memories, pastoral flashes of green, unsullied fields. But there are also the painful, bitter memories of a racially quarantined existence. “The Blacks lived in what you might call the outskirts of town,” said the soft-spoken McMillian. “The sign between where we lived and town said ‘Welcome to Raeford.’ I didn’t know any white kids until I came North.”

Separated from her husband, Jim’s mother moved to New York City to grab whatever opportunities she could working in a dress factory. Two years later, when Jim was 13, she sent for her three children. They had no choice but to settle in the slum section of Brooklyn’s East New York, a decaying neighborhood that spawned dope pushers, hustlers, and gangs.

Though pockmarked with pool rooms, musty bars, and seedy luncheonettes, Jim’s neighborhood did have strips of asphalt schoolyards and playgrounds where a kid could run up and down a basketball court rather than with a gang. But it wasn’t easy. “I had grown inward,” McMillian said. “The city was a strange land. I was unsure in terms of my ability to relate to anyone. I played football and baseball all my life, but in the city, there just weren’t the facilities. I had never played basketball before.”

But Jim was the tallest student in his junior high class and, after his second day in school, his history teacher introduced him to the basketball coach, Artie Epstein. “Artie did all the talking,” cracked McMillian. “I was too shy to say a word. He introduced me to the players. They lived in the neighborhood, and we walked home together. A week later, I worked out with the team. I didn’t have any sneakers. Artie spent endless hours helping me. I began to trust him. He is one of the few whites I’ve ever been open with.

“I began to use basketball, as a means of communicating, of expressing myself. I was terribly self-conscious of my Southern drawl and my clothes. And kids will let you know if you differ from them.”

But even making it in basketball, the guts of his neighborhoods culture, could not soothe all his fears. McMillian soon learned that the gray, steel jungle of the ghetto frames a perverse and muddled tintype of pure acceptance. “Other kids got their kicks showing how much man they were,” he recalled. “Mine was basketball, but in a way it alienated me from the rest of the fellows. They smoked grass and drank cheap gin. They spent their days and nights playing craps or cards. I didn’t, and they hated me for it.”

McMillian survived by playing basketball each day until his arms and legs went limp. It depressed and disgusted him to spend much time at home, where four people shared three rooms with the rats and roaches that feed on cankered tenement buildings with the tacit approval of the slum landlords. So we played ball before breakfast and after school.

He hated the humid, sticky nights, but his misery was tempered by the bright lights that shone above the tattered playground near his home. He would sleep until midnight and then flee to his lonely half acre of concrete to practice his moves and sharpen his eye from the corners. After a few hours, he would be so tired that the heat and roaches didn’t bother him.

“Once,” recalled McMillian, smiling distantly, “when I was jumping rope to build up my legs, a cop came over and talked to me. I guess I looked kind of strange. A kid jumping rope in the playground at one in the morning. That was the only time I remember anybody coming around.”

The lonely nights soon faded in a whir of national recognition as more than 150 colleges bartered for the star from Thomas Jefferson High School. But McMillian promised himself and his mother that he would seek the best education possible. He almost enrolled at UCLA, but the comely trappings of the campus were too exotic for him, and he thought they might be too distracting. “I had seen too many guys come and go, some of them with busted knees. They played somewhere for four years and never got that little piece of paper. I didn’t want to be stereotyped. Columbia offered me the best scholastic program.”

During those four years at Columbia, McMillian majored in sociology and put his classroom experience to constructive use. The summer months found him working as a coordinator for Operation Sports Rescue, an agency of the city’s anti-poverty program. Together with such athletes as Lew Alcindor and Walt Frazier, he traveled through the playgrounds of his youth, and beyond, listening to kids and offering advice and encouragement.

He said: “I could relate to them because I had grown up in neighborhoods just like theirs. It wasn’t a clinic. We didn’t speak in terms of playing ball. They didn’t need that. We wanted to dialogue. We talked in terms of college, what to expect when you’re being recruited, college board scores. It was part of a rap session.”

McMillian also brought his program to Riker’s Island prison in New York. He was struck by the number of inmates he knew from the playgrounds; he had played pick-up games with some only weeks before they were interned. “It caught me off guard,” he said haltingly. “What could I say to them? I knew one guy there who was in for three years for armed robbery. Man, he beat up an old man for 64 cents. It made me wonder if I had let anyone down somewhere along the way.”

But the self-effacing McMillian has remained aloof from any ideological confrontations and rarely offers an opinion on the swirling, heated racial issues of the day. Much of this can be traced to what one might consider his painfully shy, often insecure, personality. He believes that the Black man’s civil rights guarantees were coming too slowly, but he was hung up on what organization to favor, which path to take.

At the moment, McMillian is keenly absorbed in exploring the political and social philosophy of the Black Panther Party. He was impressed with Bobby Seale’s Seize the Time, and he says the book helped crystalize some of his own racial feelings.

“I think the Panthers are vastly misunderstood,” he says now. “You never hear about their breakfast programs or their fight against the dope pushers in the ghetto. Unfortunately, too many people are influenced by the media; they are never really aware of what has happened. During the Columbia riots, I was shocked to read some of the inaccuracies in the papers. So, when Seale writes that the media is misinformed, I tend to believe him.

“I’m also familiar with police tactics. Everybody in my neighborhood knew the cops used to plant stuff in pushers’ cars to make a pinch. Now, I’m not saying those guys didn’t deserve to be put away, but the method is questionable. The Panthers have much to contribute. If I were politically oriented,” he says thoughtfully, “I’d align myself with the Panthers.”

Socially and financially insecure for most of his life, he doesn’t want to jeopardize his chances to see what it’s like on the other side. McMillian is well on his way to achieving some of that financial security. He was the first-round draft pick of the American Basketball Association’s New York Nets, as well as that of the Lakers. Accompanied by his lawyer, McMillian first talked with the Nets’ owner Roy Boe.

He never expected the Laker owner to top the Nets’ offer, but he did, and McMillian signed a lucrative three-year contract with the Lakers. “It’s not that we’re in competition with the ABA,” Jack Kent Cooke told him. “We picked you first, and we’re willing to pay for you.”

McMillian immediately phoned Boe from Los Angeles to tell the Net owner he had signed with the Lakers before the story broke in the papers. “I guess I could’ve got a higher price. But I didn’t want to play a game of ping-pong with the owners. That’s not me. I wanted to conduct myself with some dignity in the negotiations. Man, I never thought I’d turn down more money. Well,” he shrugged, “I guess that’s growing up.”

Considering today’s burgeoning crop of basketball talent at the college level and the growing sophistication of professional scouting, first-round draft choices aren’t likely to have any glaring weaknesses. McMillian is no exception. But that isn’t to say that there aren’t facets of his game that will have to be polished in order for him to endure the rigors of the National Basketball Association. Significantly, McMillian was generally regarded as an inadequate ballhandler. He was often frustrated in his attempts to dribble the ball for any length of time.

But if McMillian is not really outstanding in any aspect of basketball, he can do everything well, according to Mullaney. McMillian’s most potent offensive weapon is his floating jump shot from the corners. He prefers to drive hard to his left, within a range of 15 feet from the basket, stop suddenly and jump. “That’s my money shot,” he says. “I can make it happen.”

McMillian made it happen often enough to score more points than any other performer in Columbia’s history, averaging more than 20 points per game in each of his three varsity campaigns.

Voted the New York City area’s outstanding player for three consecutive seasons, McMillian dazzled the opposition with his uncanny accuracy; in his senior year, for example, he averaged less than 20 shots per game. In contrast, the Calvin Murphys, Pete Maraviches, and Austin Carrs often took from 35 to 40 shots per game to climb the record lists. “Jim is completely unselfish,” said Columbia coach Jack Rohan. “He never rattles. He takes only good shots.”

But, more importantly, McMillian cared about his defensive play. The droopy-eyed Rohan, a man not given to cheap superlatives, excitedly described him as one of the best one-on-one defenders in college last year, the man who drew the toughest assignments in the big games. And it wasn’t simply because he harassed the man with the ball; he clung to his man like a wet rag, blocking his route to the basket and, at times, effectively denying his opponent the ball. His quick hands, facile court sense, and dogged persistence enabled him to hold stars such as Davidson’s Mike Maloy, Purdue’s Herm Gilliam, and Villanova’s Howard Porter far below their season’s averages.

Despite his size, McMillian can break in at forward because, with the menace of Wilt Chamberlain at center, the Lakers really don’t need strong rebounding cornermen. “I am satisfied with Jim at forward,” said Mullaney, who can recall being impressed with McMillian’s play in high school. “You don’t have to be a giant to play forward in the NBA. Jim’s an intelligent player. Physically, he’s much quicker than defenders anticipate. And on defense, he maintains good position and blocks out well.”

McMillian has settled in Inglewood and says he is “grooving on the new scene” in the Los Angeles area. “I just may bring my whole family out here and leave New York for good,” he said, rubbing his stylish bushy sideburns. “Just going downtown in New York is a hassle. You have to regulate your whole life according to traffic patterns. It’s more relaxed out here. People aren’t as cynical. And I’m certainly not going to miss the snow and the strikes.”

But there are some features of city living that will never change, especially for basketball players. During the summer, McMillian helped other Lakers give basketball clinics each Saturday at Sears & Roebuck stores. It was here he met Jerry West and Elgin Baylor. “You know,” he said, “what really impressed me about West and Baylor was their love for the game. They’re down-to-earth men, always willing to help.”

Recently, McMillian returned to his old neighborhood. Many recognized him; some pumped his hand and wished him well. But there were those, the hungry playground battlers, hunched and tense in shredded sneakers, who refused to be impressed. “See those kids,” said McMillian, pointing to a cluster of bare-chested kids poised beneath a crooked hoop. “They couldn’t care less about my press clippings. I understand their attitude. Man, I lived it. They’re burning for the chance to play against me. They’re not looking to show me up; they just want to prove to themselves that they can hold their own against me, so they know what to expect if they get to college.

“Some of those kids look like they’ve lived a couple of lifetimes.” Then, slowly, Jim McMillian walked across the playground to where the players were waiting, and explained softly: “I was one of the lucky ones.”

[Let’s finish up with a chapter on McMillian from the teen-oriented book titled Basketball: The New Champions. I believe that this tall, thin book was published in 1973, though a date isn’t listed. The author is Kent Hannon, who was staff with Sports Illustrated. He later moved to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Georgia Magazine.]

****

On November 5—10 games into the 1971-72 season—the Los Angeles Lakers beat Baltimore 116-110 for their seventh victory of the year. They didn’t lose another game in 1971, and their winning streak rolled on to an incredible 33 games before they were defeated on January 9, 1972 in Milwaukee. This was just one of eight NBA marks Los Angeles set during this, the greatest season in league history, including most games won in the regular season (69).

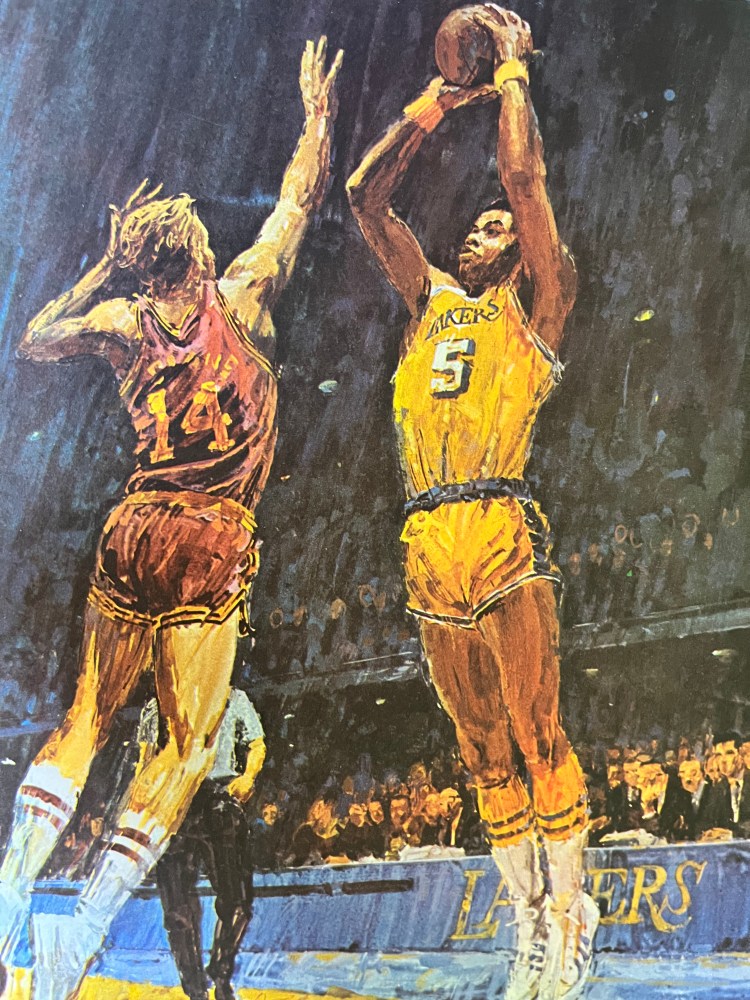

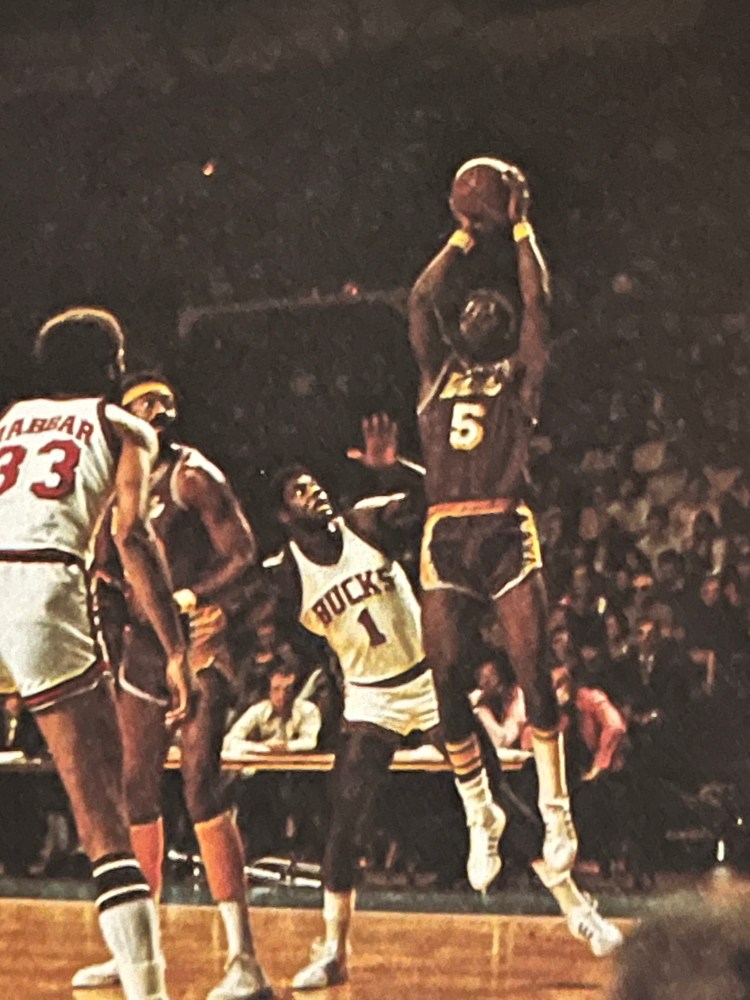

The extra added ingredient in the Lakers’ “impossible dream” year was young Jim McMillian. He played more minutes than anybody else on the team but Wilt Chamberlain, more than doubled his scoring average from his rookie year, and shot opposing defenses to shreds from his home on the left baseline 15-18 feet away. In addition, he was usually given the responsibility for stopping the other team’s best offensive forward. At 6-5, this assignment required a great deal of strength, hustle, and experience he didn’t yet have.

McMillian got his chance to start for the Lakers when Elgin Baylor retired. Baylor, the greatest forward in NBA history—the man of 1,000 moves and 3,000 head fakes—had thrived on the Lakers’ traditional slow-down, set-it-up offense. But even with Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain as teammates, he had never been able to give Los Angeles an NBA title.

As the frustrating years went by, Baylor’s knees got worse, and in 1970-71 he was able to play in only two games. When he came back the following year for a final fling, having just turned 37, it was not merely to sit on the Lakers’ bench and help out when needed—his pride would have never allowed that. But he couldn’t take the pace and, after the ninth game of the season, Baylor let youth have its way.

Enter McMillian—a strong, sharp-shooting forward with a New Yorker’s court savvy. Bill Sharman, the ex-Boston Celtic star who was the Lakers’ new coach, had committed the team to an all-out running game and put them through a grinding conditioning program in training camp. McMillian fit right into the new offense.

Typically Chamberlain, who led the NBA in rebounding for the ninth time, would start the Laker fastbreak by getting the ball off the defensive board and pitching it down to either McMillian or Gail Goodrich, who frequently headed downcourt as soon as the opponents shot. So confident was Sharman of their shooting abilities that he gave McMillian and Goodrich carte-blanche to fire away whenever they felt comfortably within range—regardless of whether rugged Happy Hairston (1,045 rebounds and 1,047 points) had gotten downcourt and into position for a rebound. Jerry West, who won an assists title to go with his 25.8 points per game, was the quarterback of the fastbreak when Wilt couldn’t reach McMillian or Goodrich with a pass.

McMillian thus gave the Lakers a dangerous scoring threat up front and took some of the heat off West and Goodrich. His 18.8 points per game gave the Lakers a fifth starter in double figures, and Hairston was freer to help Chamberlain on the boards.

Jim McMillian’s facial appearance—droopy eyes and sheepish look—conveys exactly the wrong impression of him. He is not about to walk off the court and catch a few zzz’s on the scorer’s table. He is sharp-witted, intelligent, and a destroyer on the basketball floor. Yet, because he tends to put on weight and sometimes looks like a Bill Cosby character who just got caught with his hand stuck in the cookie jar, McMillian has been a constant subject of jokes by his teammates and friends.

Jim was the Lakers’ first draft choice in 1970, and he came to them by way of Columbia University in New York. Three times before that, he had been the Haggerty Award winner as the best high school player in the city. His play in Ivy League basketball measured up to his high school notices.

His first triumph came in the 1967 New York Holiday Festival held in the old Madison Square Garden—the last holiday event to be played in the soon-to-be demolished building. Columbia drew highly regarded West Virginia in the opening round of the tournament. McMillian poured in 40 points, and Columbia won the dubious privilege of playing Louisville, a team led by All-Americans Wes Unseld and Butch Beard. But the Lions upset the Cardinals, as Rhodes Scholar Heywood Dotson and Dave Newmark took care of Unseld and Beard, and McMillian hit for 24 points. He topped himself by one in the championship game against St. John’s to give Columbia a 60-55 victory, and he was named the tournament’s Most Valuable Player. Columbia went on to win the Ivy League title and an NCAA berth in March.

McMillian’s desire to achieve the maximum from his natural ability is a motivation he developed as a youngster in Raeford, N.C., and during his high school days in Brooklyn’s East New York section. He chose to accept the tougher academic challenge of an Ivy League school and a good education. McMillian already knew he could play basketball and, as time would tell, he was right. Over his 77-game Columbia career, McMillian averaged 22.4 points per game and tallied 1,758 points.

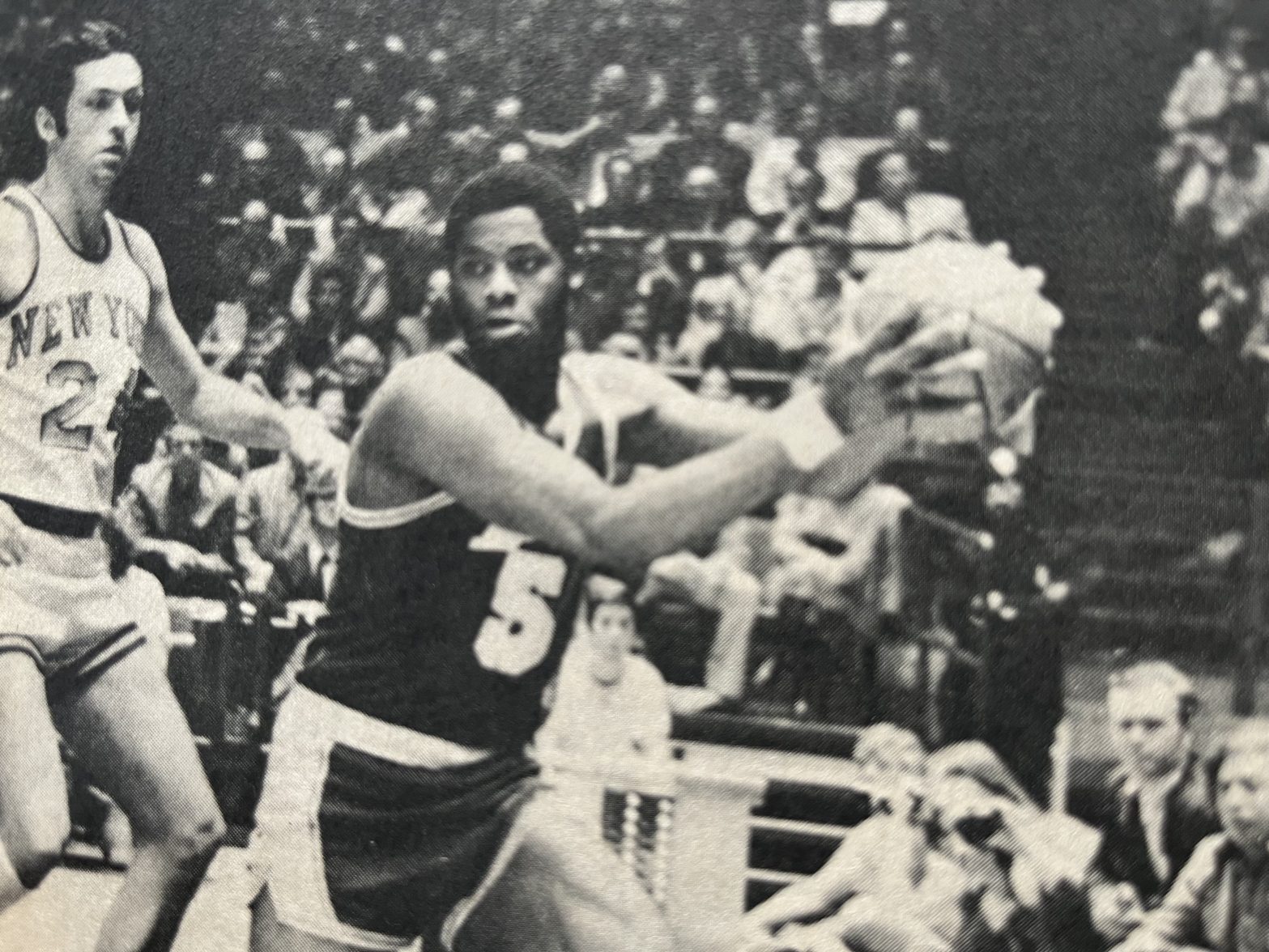

McMillian started his rookie year with the Lakers as a reserve forward splitting time with Keith Erickson. He would have started on other teams in the league with less depth than Los Angeles. A knee injury to Jerry West forced coach Joe Mullaney to move Erickson to guard, and Jim was inserted as a starting forward.

He missed playing in only one game all season and averaged 8.4 points per game. But he wasn’t yet in the lineup to shoot the ball, and he fouled out of only one game. After defeating Chicago, the Lakers were crushed by the Bucks in the 1971 Western Conference finals. McMillan, whose shooting always seems to improve under pressure, climbed to a 15-point average in a dozen playoff games.

One year can make a big difference, and to show that their 69-13 season mark in 1972 was an indication of even greater things to come, the Lakers drilled a fine Chicago Bulls team in four straight games in the first round of the playoffs. Then they were humiliated by the Bucks, 93-72, in the opening game of the conference championship, and it looked as though Los Angeles was again falling apart in the clutch. Not so.

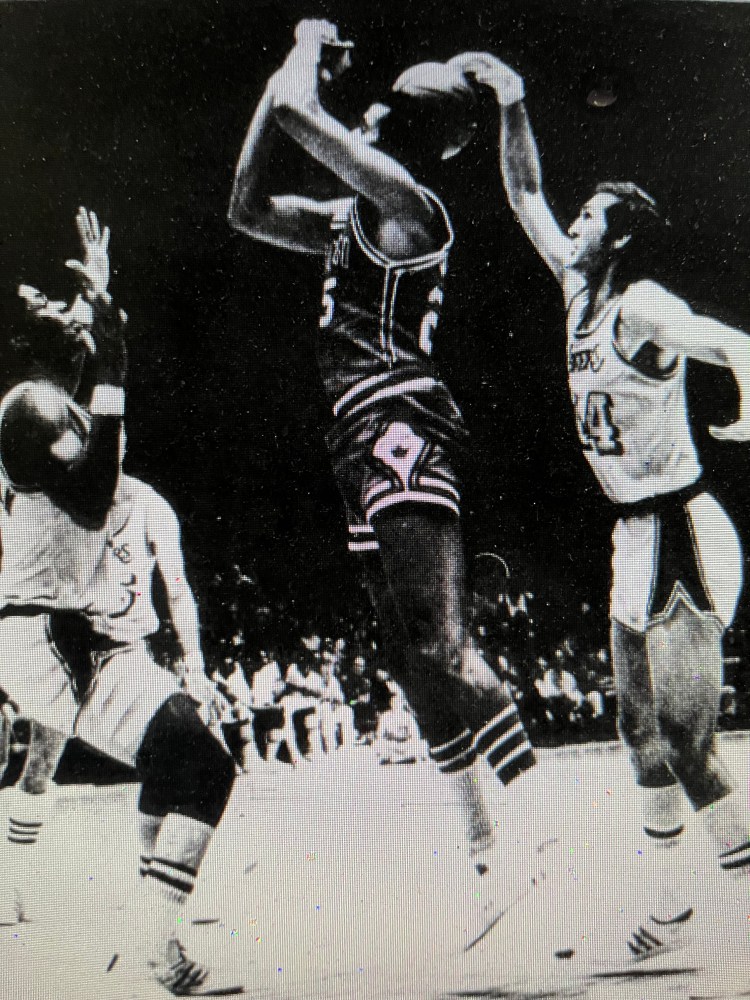

McMillian, who had just played the worst game of his career (3 of 20 from the field), nailed 16 of 25 shots in the second game against Milwaukee and led the Lakers to a victory they could hardly have expected. The Bucks, after all, shot an extraordinary 61 percent from the field. McMillian outscored Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, 42-40.

Though they beat Milwaukee in six games, the Lakers still didn’t exactly look like winners. The Bucks had outscored and outshot them, and here was the Eastern Confernce-champion New York ready to do the same. In the first half of the game in Los Angeles, the Knicks hit the Lakers with 72 percent shooting and won going away, 92-84. McMillian again had a bad game offensively, and his man—Bill Bradley—went wild with 11 of 12 from the floor and a game-high 29 points.

Despite the Knicks’ initial outburst, the rest of the series was no contest. So much so that Jim McMillian scheduled a tennis match in Los Angeles on a day when a less-confident man might have expected he would be in New York for the sixth game of the series. The Lakers won in five, and McMillian averaged 20 points per game.

McMillian sipped a glass of victory champagne as Jerry West delivered a short toast. “When we went to training camp last fall,” West said, “I thought we’d win our division but never get past Chicago or Milwaukee into the finals.

“We were a team with a lot of lacks,” he smiled at McMillian, “but Coach Sharman fit us together perfectly.”