[Point guard Mark Jackson played his first five NBA seasons (1987-1992) with the New York Knicks. The following article chronicles Jackson’s career during seasons one through three. As the headline suggests, what goes up must come down, and Jackson was falling fast in New York. “Let’s make one thing perfectly clear,” wrote one commentator in 1991, “Mark Jackson has to be a starter—a 30-35-minute-a-game kind of guy—to be effective. If not, the ‘man’ is bound to be an unhappy camper, as the Knicks found out.”

The Rise and Fall of Mark Jackson appeared originally on March 25, 1990 in the New York Daily News. I found it republished the next season in the January 1991 issue of Basketball Digest. The byline belongs to Fred Kerber, who would later write become a staple at the New York Post.]

****

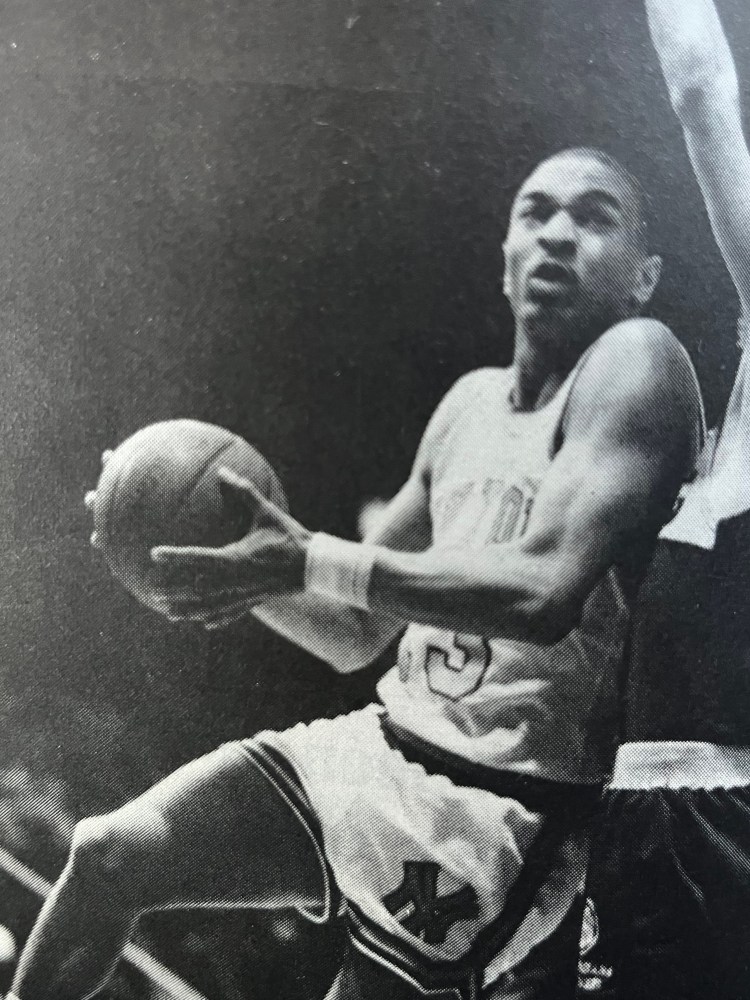

For one glory-filled season, Mark Jackson was a god with the New York Knicks. He beat the odds and overcame physical shortcomings the experts claimed would limit his pro career. The Knicks, selecting 18th in the 1987 draft, took a chance on the kid from St. John’s via St. Albans, Queens. No one could have foreseen the dividends that Jackson would return. He became Gotham’s gift to itself, one of New York’s most-popular athletes.

The Knicks, under rookie coach Rick Pitino, opened the 1987-88 season with a hard-fought loss at Detroit, then an embarrassing blowout in Indiana. The Knicks had been soundly booed at Madison Square Garden in the preseason, so Pitino struck upon an idea to win the crowd for the home opener. He wanted Jackson introduced first among the players. “No one in New York would ever boo Mark Jackson,” Pitino rationalized.

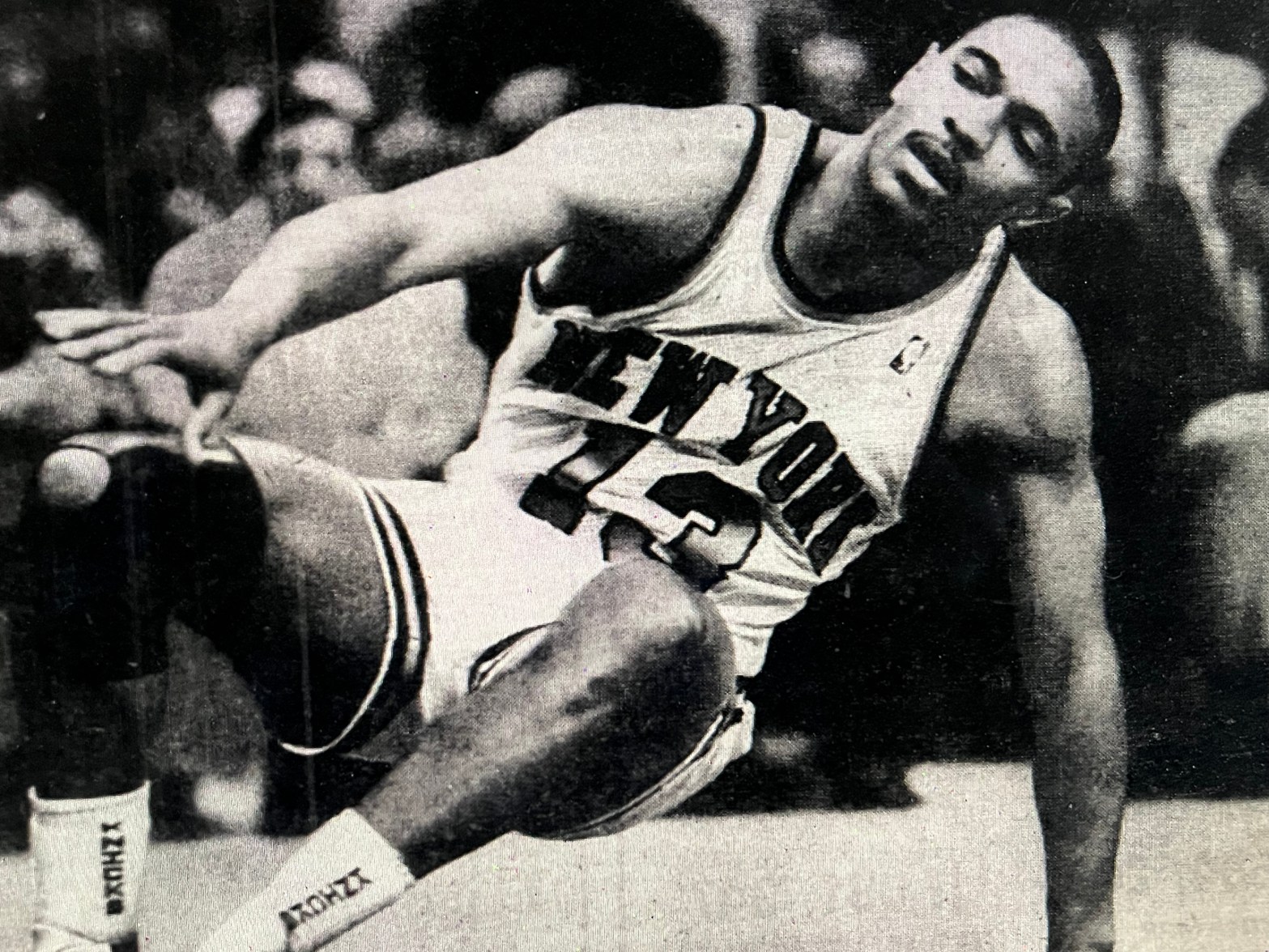

Oh, how times changed. When? Where? How? Why did a young player who so captivated a city fall from favor so quickly and thoroughly? In every Garden game last season, Jackson’s first missed shot or turnover was treated like a criminal offense. Jackson was shell-shocked, hurting inside, playing tentatively outside. He said it was “unfortunate.” He looks back and honestly can’t figure out how something so sweet went so sour.

The Viewpoints

“He lost the city when Rick Pitino left for Kentucky,” says former teammate Sidney Green. “Rick Pitino had the city on the edge for him. Rick Pitino told Mark Jackson he was the next best point guard to Magic Johnson, and Mark believed it. Rick Pitino lied to Mark Jackson.”

Some offer sympathy. “I love the kid,” says St. John’s coach Lou Carnesecca. “It bothers me. If you’re cheering for the Knicks, you should be cheering for Mark Jackson.”

Others offer smug smiles. “Hey, he brought it all on himself,” says one of Jackson’s current teammates. “It went to his head, and he thought he was better than everybody.”

The public definitely turned. What once was seen as confidence on Jackson’s part became perceived as unforgivable arrogance. “It’s probably a combination of a lot of things,” says Knicks legend Walt Frazier. “His flamboyance on the court, what he said about wanting to be the hero. It’s something that steamrolled coming into the season. I never thought it would get to this magnitude.”

November 22, 1989 vs. the Lakers

Mark Jackson hears Garden boos for the first time. In the stretch of a 110-98 Lakers victory, he commits heresy: He tried to out-magic Magic Johnson. He is woefully overmatched in a 6-for-22 shooting night that included seven turnovers. His shots are poor. After the game, he claims he didn’t play badly.

“New York wants a sign of weakness in its heroes,” theorizes Pitino. “New York doesn’t want perfection. Deep down, he is a very emotional, very sensitive kid. Mark doesn’t show that publicly. But he did behind closed doors. He would admit, ‘Coach, I screwed up.’”

The Competition

The Knicks draft point guard Rod Strickland in June 1988 and immediate questions arise. Why do the Knicks want another point guard? And for the first time, Jackson has a real threat to his job. In his rookie year, after veterans Rory Sparrow and Gerald Henderson are cast adrift, Jackson has little competition. As the 1988-89 season progresses, there is a distinct division among the crowd, as many want more minutes for the vastly talented Strickland.

“The thing there,” says GM Al Bianchi, “was that even though Rodney had talent, we said, ‘Hey, this guy [Jackson] did it for us.’

“I don’t understand a lot of it. They tell me they once trashed Patrick Ewing’s posters, and we saw what they did to Kenny Walker. Thank God for the Slam Dunk [Championship won by Walker in 1989]. But I’ve never seen it before where the home fans boo one of their own. This may be New York, but that doesn’t make it right.”

The Contract

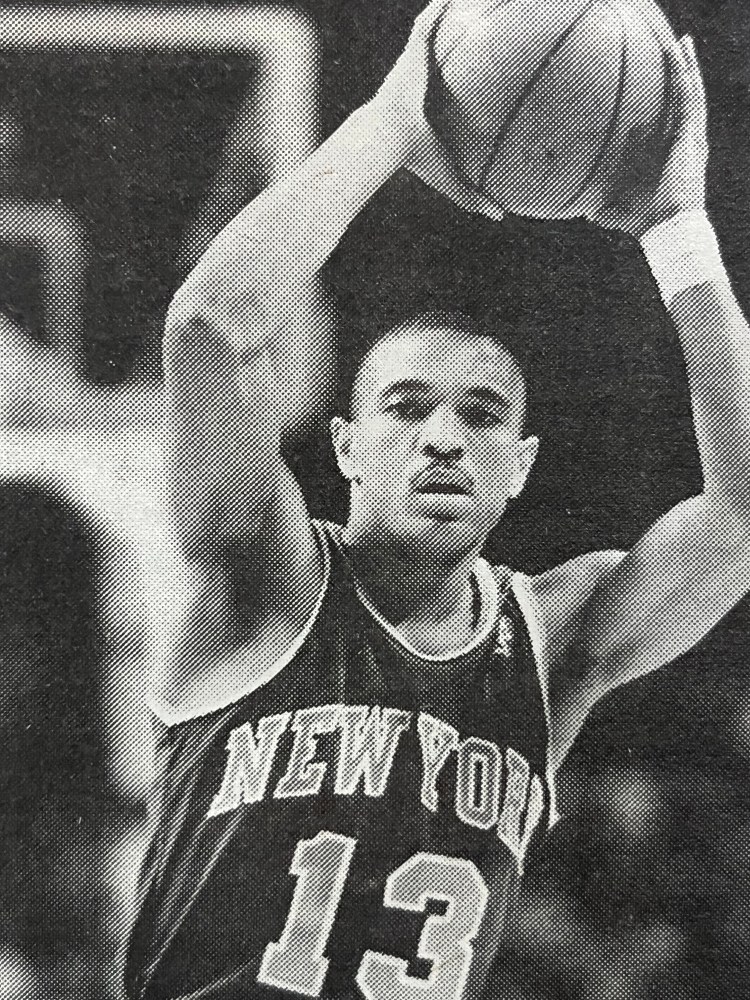

For a season plus, Jackson has been underpaid by league standards. He is Rookie of the Year and earns a spot on the 1989 all-star roster—but without financial reward. Contract negotiations have been long and messy. Agreement comes January 27, 1989, while the Knicks are on the road. More than two months shy of his 24th birthday, Jackson is a millionaire.

“Everyone in the city said, ‘Give him the money,’” Green recalls. “Now everyone says, ‘What did they give him the money for?’”

It was Jackson’s multimillion, five-year contract that helped keep him in New York. Sources confirmed the Knicks tried to deal both Strickland and Jackson before the trading deadline last spring. But with Jackson’s contract, nobody wanted him—or could afford him.

The Quote

Throughout his rookie season, Jackson wins game after game for the Knicks. He is the team’s best money player as last-second heroics become commonplace. “I refuse to be the second-best player on the court,” he says. His bravado and courage are applauded. Later, when the shots miss, he is considered a selfish, glory-seeking twit with an inflated opinion of his ability.

“I remember after one game,” Green says, “Rod Strickland was ticked. He had played poorly, and Mark played well. So me, Rod, and Mark were in the shower. Mark looked at me and said, ‘Who’s the best point guard in the league?’

“I couldn’t believe he’d say that with Rod right there. Rod just turned away. I looked at Mark and said, ‘Magic Johnson.’ Mark stared and said, ‘OK, who’s next?’ I wanted it to end, so I did with a lot of people did—I kissed his butt. I said, ‘You are.’ He nodded and said, ‘Thank you.”

The Showboating

Jackson, a firebrand of emotion, delights the Garden crowd with his dazzling plays. He is praised for exuberance. He is later cursed for hot-dogging. “He’s the biggest [bleep] in the league,” says one major NBA star. “He had one good year, and he acts like that?”

Don Cronson, Jackson’s agent, doesn’t understand the crowd’s disdain for Jackson. “What has the guy done?” Cronson says. “All he did was help excite a franchise that was a dead-letter office on Sunday and help it to the playoffs. People don’t like the finger-waving, but the thing is Mark plays his best from that element.”

The Shot

After his three-pointer with 16 seconds left to help bring victory in Game 1 of the 1989 playoffs against the Sixers, Jackson tries his hand again—from longer distance—in Game 1 against Chicago. He throws up a huge brick. The Knicks lose the game, the homecourt edge, the series. There is no praise, only scorn.

“Mark saw the zenith, now he is seeing the nadir,” Pitino said. “All I did with Mark was say, ‘You’re my leader,’ like I did with Patrick. I wanted to give them full confidence—confidence to take the big shot. He missed that one. Just like he may have gotten too much credit when things went right, he is taking the brunt of too much blame when things went wrong.”

The Quote II

Jackson is booed lustily in Game 5 of the 1989 Bulls series. The city he once owned has turned on him. Afterwards, in a false display of macho, he claims the fans “are like rats leaving a sinking ship.”

“It was a statement that never should have been made,” Pitino says. “But over one statement, don’t lose sight that he is still a young man. And young men make mistakes.”

The 1989 Training Camp

Jackson, having undergone knee surgery in March 1989, is told to take a summer off. He does, but he reports to camp grossly out of shape. Still, new coach Stu Jackson flatly states, “Mark Jackson is my starter.” Jackson pulls a muscle in preseason and winds up far behind teammates in conditioning.

“He was told to take off because of the knee,” Cronson says. “He had never been out of shape in his life and didn’t even realize he was. He figures, ‘I’ll go through three or four two-a-day sessions, and I’ll be fine.’ Yeah, he should have cranked it up a few weeks before camp.”

The Media

Jackson is the darling of the press for a season. He contemplates answers, replies concisely, says all the right things, speaks of team. As “I” filters in more and more and his play dips, the criticisms mount. “Make no mistake,” says Detroit assistant Brendan Malone, a former Knicks aide. “Fans in New York are influenced by what they read.”

Jackson, once a confident performer with all-star status, became a tentative, almost passive player. He played “not to make mistakes,” Stu Jackson says. The boos came when he entered the game. They swelled with each miss, with each errant pass. It was unrelenting, unforgiving.

“I know it affected his play,” says Frazier. “In certain situations, he was passing the ball sooner, not penetrating as far as he did.”

Can Jackson reclaim the city he once held in his grip? Or is the damage beyond repair?

“I think he can,” says teammate Trent Tucker. “He has to continue to be himself—that’s the most important thing. He has to know the things he can do and just do them.”

Says Carnesecca: “He wasn’t always top dog, not in high school, not elsewhere. Look at his career. Always, he rose to the top. He has done it before. I honestly believe he can do it again.”