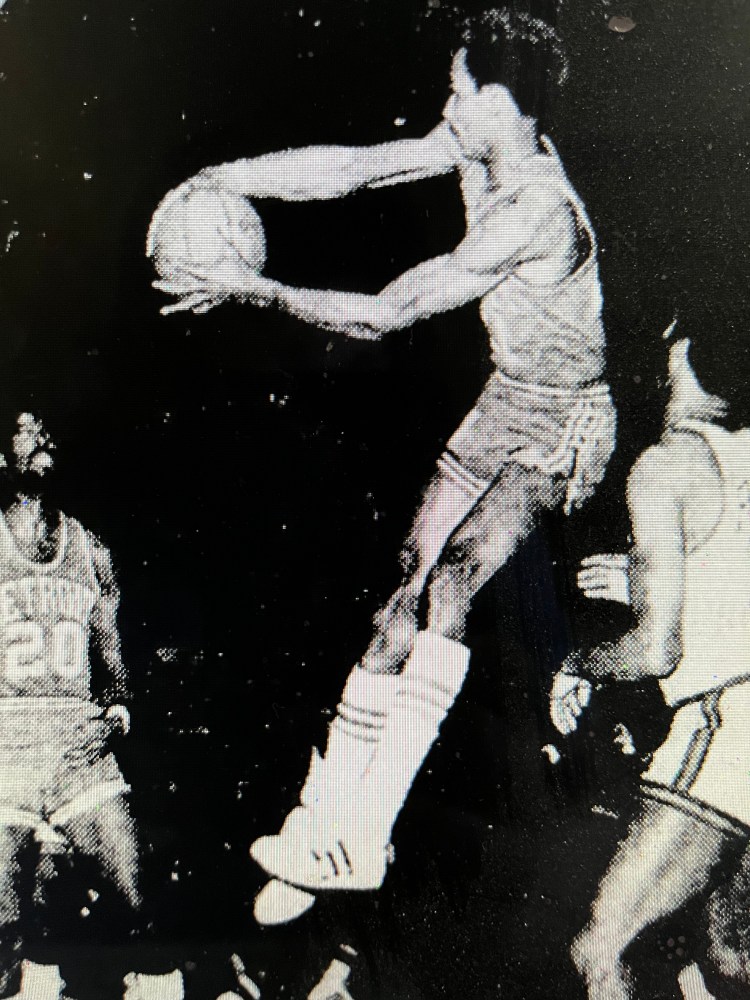

[In 1968, if you mentioned “the Big O,” most people would think of Oscar Robertson. But for many pro scouts, the nickname also elicited the extra-long, extra-lean image of Otto Moore, the nation’s other Big O and mostly quietly so. The celebrated 6-foot-11 center at tiny Pan-American College amounted to a hidden gem. In fact, some pro scouts insisted that this other “Big O” would be the next Bill Russell, an elite defender and a natural shot-blocker.

At the tryouts for the 1968 American men’s Olympic basketball team, Moore didn’t look too Russell-esque against some of the bigger college names. And so, he slipped to the Detroit Pistons as the sixth overall pick in the 1968 draft. Detroit fans soon grumbled through his mistake-filled rookie and sophomore campaigns. But by his third season, Moore started to find his rhythm in Detroit. That, of course, didn’t stop the Pistons from drafting big Bob Lanier first overall in the 1970 draft, making the rail-thin Moore expendable in Motown. It also was clear by Lanier’s arrival that Moore wasn’t the next Russell—or even the next Big O.

Still, Moore got in nine NBA seasons on five teams (1968-1977), finishing with career averages of 8.2 points, 8.2 rebounds, and 1.2 blocks per game. It’s unlikely that Moore ever sat for a magazine-length profile. But this article, published on March 17, 1970 in the Detroit Free-Press, is almost as good. The veteran Detroit sportswriter Jack Saylor provides the words.]

****

From their resting place in the NBA cellar, the Detroit Pistons obviously have only one direction to go. But the dawn of a new decade has fostered hope that the climb may be swift, principally because Otto Moore’s playing statistics are approaching the size of his appetite.

When the Pistons picked the lean Pan-American center as their No. 1 draft choice two springs ago, fans said: “Otto who?” Then, after his freshman NBA season, the cries turned to “Otto, boo-hoo.”

“Last year, my confidence was gone. I had lost it all,” the 6-foot-11 Moore recalled. “It didn’t seem like I could run or shoot or jump or do anything right. Some guys step in from college in their first year and go real strong. Other guys take two, three, four years—I guess I was one of those. I was real disappointed.”

Former Detroit coach Paul Seymour made the Dave DeBusschere-Walt Bellamy trade and was committed to the Big Bell as his center. But Seymour yielded to Bill van Breda Kolff this winter and, after a couple of months of juggling, VBK turned the pivot job over to Moore, the gangling, 23-year-old Floridian.

“One night, he played me and just let me go,” Otto said. “He didn’t pull me out if I threw the ball away or if someone beat me and made a basket. So, the whole thing was mostly a matter of the coach having confidence in me.“

****

The night in question was January 2 against the Boston Celtics. Moore had been averaging merely 15-16 minutes a game, but VBK used him 39 minutes that night. The Pistons lost that night, but the meshing process was started. Suddenly, Detroit wasn’t losing badly, then . . . viola! Soon the Pistons were winning as often as they lost. It was a start. Moore began to toll 40-44 minutes a game as Bellamy went first to the bench, then to Atlanta.

Since that pivotal night of January 2, Otto has averaged 17.4 points and 15 rebounds a game. If the latter number were projected over the whole season, it would be the same as the NBA’s third-ranked board man, a fellow named Lew Alcindor.

It hasn’t come easily for the likable young giant, who didn’t get the early basketball education that most of his contemporaries did. “I had never even played on the playground,” Otto remarked of his childhood in Miami. “My mother wouldn’t let us go too far from home, and the playgrounds were about 15 blocks from where I lived.

“I was pretty tall in the ninth grade, and the coach stopped me one day and said, ‘Come on down to the gym, practice is at three o’clock.’ I didn’t go, and he asked me why. I told him I didn’t know anything about basketball, and he said, ‘That’s what I’m here for.’ I went the next day, but it didn’t last. I quit in about a week.”

“He’s sensitive,” observed Dave Bing, who along with Jimmy Walker, is Otto’s closest friend on the Pistons: “He gets down on himself. People yell at him, and his feelings get hurt.”

Otto really took an interest in basketball as a 10th grader, but his sensitive nature held him back. “I really wanted to play, but the coach didn’t let me—he was concerned about grades, and mine weren’t too good,” Moore remembered. “I finally got them up, then in practice we scrimmaged one day, and we were throwing the ball away. One guy tried to go behind his back with the ball. Another guy stole it, and I laughed. The coach told me to go hide, so I gave it up that year.”

The next year, Booker T. Washington High got a new coach in Walter Caldwell. “He talked to me and told me they could build a team around me and this could be a good year, so I stayed out.”

Moore did fairly well, then became consistent as a senior, made all-city, and was directed to Pan-American by Caldwell. “I wanted to go to Syracuse when Bing was there,” Otto said. “I didn’t know him then. But they had a couple of 6-foot-10 guys that weren’t doing anything—Dave was the leading rebounder, and I just knew I could go up there and be the leading rebounder anyway.

“Then they showed me a picture of all the ice and snow, and I changed my mind and said, ‘Noooooo.’”

****

Weight, rather the lack of it, has been a handicap for Moore, who looks like he’s never been bothered by pulled muscles for lack of muscles to pull. Otto, who has a 33-inch waist, has only 214 pounds stretched tautly over his 6-foot-11 frame. But he’s deceivingly strong. Still, he could use extra poundage against the Willis Reeds and Wes Unselds—and it isn’t that he doesn’t try.

Moore offered a sample menu as evidence. “There’s this soul place I go in, I might order pork chops,” he said for openers. “I love rice, so I might get three side dishes of rice, two side dishes of corn, or a side dish of peas, corn muffins, two glasses of lemonade, candy sweets, and dessert.”

“And he always drinks pop (soda) for breakfast,” added Bing, who often watches with amazement at Otto’s calisthenics in the knife-and-fork league. “I’ve told him I’d support him any other way, except cooking his meals,” Bing chuckled.

“We got into a town late one night, and five or six of us sat down. Otto started ordering, and the waitress thought he was ordering for all of us. He had enough for three people—she couldn’t believe it, she said she wanted to sit down and watch him.

“It’s nothing for him to sit down for breakfast and have six eggs, a double order of either sausage or bacon, then order pancakes.”

“I got up to 220 in the offseason,” Moore sighed, “but with all this traveling and running night after night, it dropped back down. Moore, who is single, doesn’t smoke and isn’t much of a drinker (maybe a frozen daiquiri or two at a party), so he spends most of his time eating, sleeping, and fretting about his game.

“I’m still not playing as well as I did in college,” he says. “Like blocked shots . . . I used to get seven, eight a game, now I’m almost not getting two a game—that’s a big fall-off.

“And I haven’t really learned how to pace myself. [Teammate] Butch Komives watches and tells me I get tired and tend to get sloppy . . . like commit a foul when I shouldn’t have to or not get back on defense. But I think I’m learning. My teammates are a big help. Dave [Bing] is always talking to me, and Walker is, too . . . also Eddie Miles before he left.

“I wasn’t hitting my jump shots at all, and Eddie would show me what I was doing wrong and what I could do to help myself. He really helped me.”

In return for their help, Moore repays by providing laughs, unwittingly, over his low pain tolerance. Bing laughed, as he recalled one instance. “We were playing Phoenix one night, and Neal Johnston undercut Otto, and he took kind of a bad fall. He was screaming, and we really thought he’d been hurt this time.

“We all ran out to him, and he was laying there screaming and yelling,” Bing recalled, complete with gestures. “When we finally got him to tell us what was wrong, he held up a finger—all this for hurt finger.

“He can’t stand pain. He doesn’t even like to take the tetanus and flu shots that we get at the start of the season. Doc Wright had to chase him all around to give him his shots.” This was a considerable feat for the good doctor considering Paul Seymour once made the interesting observation that Otto can run faster backwards than most players can forwards.

Most of the pain these days, however, is being inflicted by Moore on the opposition. “Last year, I knew if I didn’t do the job right away, I would not play,” he said. “There were times I played good one game, then the next game, I wouldn’t get in until maybe the third quarter. Now, van Breda Kolff just lets me play. He thinks I have the talent to do it, and he is letting me play.”

The Pistons, getting their first solid center play in years, may well be on the way up—that is, as long as Otto’s meal money holds out.