[In August 1996, the Houston Rockets traded four players, including the athletic, 26-year-old forward Robert Horry, to the Phoenix Suns for Charles Barkley. Following up on this blockbuster trade, the Suns’ in-house magazine Fastbreak ran the following profile of Horry in its December 1996 issue.

The timing of the article wasn’t the best. Horry lasted exactly 32 games in Phoenix, where he battled through injuries, struggled to didn’t fit into the system, and famously flung a towel into the face of coach Danny Ainge. By January 10, 1997, the Suns unloaded Horry to the Los Angeles Lakers, where he got his NBA career very much back on track. If you liked Big Shot Bob’s game over his 16 NBA seasons, you’ll enjoy this cradle-to-Sun story on Horry by writer Jeramie McPeek.]

****

Kids can be so cruel.

When Robert Horry was a child growing up in Andalusia, a small town of about 11,000 in Alabama, his classmates would always poke fun of him, tease him, and whisper behind his back. So much so, he pretty much kept to himself. That’s probably the reason he’s quiet around those who don’t know him very well to this day.

You see, Robert wasn’t like the other kids. In the first grade, he was as tall as his teacher. Tall, lanky, skinny, like a bean pole. And with his big feet, he was awkward, too. More often than not, he would be left standing on the side of the court when the boys would choose up sides to play some hoops.

“People hate to admit that they were clumsy once in their life, but the fact is, I was real clumsy,” he said. “So guys would play basketball, and I would never get picked. I wasn’t the type of kid to sit around and pout, though. I didn’t get picked, so I went home and did other things.”

By himself. But there were lots of “other things” to do. He’d toss a tennis ball onto the roof of his grandmother’s house, where he and his mother lived, and then go diving to catch it rolling off, each time in a different spot.

He’d grab his BB gun and go out into the woods behind the home, hunting birds and squirrels. Something he’d often wake up at the crack of dawn to do. Or maybe he’d hop into his go-cart and speed through the neighborhood. One time he was brought back to his house by an older gentleman who found Robert trapped beneath the vehicle after he had flipped it making a sharp turn.

And if it was rainy outside, he’d play video games, something he still likes to do today. “As an adult now, he’s into that,” said his mother Leila. “You can be talking to him on the telephone, and you’ll know when he’s into all those games on that darn TV.”

In fact, Robert now has three life-size arcade games in his home as well as stacks and stacks of Sony PlayStation disks. Many of his basketball games even have himself as one of the players to choose from. He said he averages about 40 points a game.

They’re not laughing anymore.

****

On July 25, 1970, Robert Keith Horry was born in Hartford, Md. to Robert and Leila Horry. At the time, the elder Robert was in the army and stationed in Maryland. But two years after the birth of their son, the couple was separated by war and never rejoined.

“If it wasn’t for Vietnam, my parents probably would still be together,” the 6-foot-10 forward said.

With her husband in Southeast Asia, Leila took her two-year-old back to Andalusia, where she’d grown up, to live with her parents. By the time her husband returned, she had become a teacher and, because he was stationed in another state, the two never got back together. “She didn’t want to give up her career because it just started,” Horry said. “They just became separated and then divorced.”

Although his father wasn’t around day in and day out, Robert still got to see him on a regular basis, taking trips to wherever he was stationed every other weekend or so. And Dad was always there to back up his ex-wife’s encouragements and discipline when needed as well. “He was one of the people that made me get my education,” Robert said with a laugh.

“One time I slacked in school, and he drove all the way from South Carolina just to give me a beating and then drove all the way back. They got on me more about getting my education than anything because at first I wasn’t into doing that.”

Just like school, he wasn’t into basketball at first either. But when his older brother Ken started persuading him to play a little in middle school, he quickly began to pick up the sport. “He got me into it, but the funny thing about it was I played it just because he was playing, and we were going to be on the same teams,” he said.

Slowly, Robert began to fall in love with the game. He’d ask for basketballs and hoops for Christmas. He’d play day after day in the local recreation center. And eventually he became one of his age group’s better players in the small town.

By the time he reached high school, the fact that he was only a 14-year-old freshman didn’t matter. The coach immediately put him on varsity, where he played with his big brother who was a senior on the squad. His talent caught up to his height, and the combination turned heads.

“High school was fun,” he said. “Best years of my life . . . those and the early college years were the best. They think now when you have all this money, you have no worries. But when you were in high school and college, you had no worries. All you had to do was go to class, study, and play basketball. It was a lot simpler.”

As his game developed, Horry made basketball look simple. He could shoot from inside or out, make crisp passes, wash the backboards, and swat shots. He was even called on to play point guard at times and push the ball upcourt. He could do it all. When he wanted to.

“That was the biggest knock I had on him,” said Andalusia High coach Richard Robertson. “I stayed on him a lot about playing with intensity. The tougher the game or the bigger the game, the tougher he was. But if it was somebody we could handle, he didn’t go all out. The best thing that could happen to us was to go up against someone who was real tough and would give us a whole lot of trouble, and he would just take over.”

Perhaps no better example was a game in which Horry broke the school’s single-game scoring record by putting up 42 points in 1986. On a night in which Robertson was being honored by the school for reaching his 200th coaching victory, Horry was determined to give him No. 201. But the opposing Northview was also determined to ruin the festivities.

“We went into three overtimes before he won it for us,” the coach recalled. “They had a guy who’s playing with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers now, Lawrence Dawsey, and he would bring them back, and Robert would bring us back. It was nip and tuck and nip and tuck, and finally we won it there at the end. He made USA Today, and everything was history from there on.”

But even with all the sudden attention he was receiving and his exploding potential in the sport, the high school star never had visions of grandeur. He never planned on playing in the NBA, and his role models were never world-renowned, multimillionaire athletes. Sure, he may have been a fan of Magic Johnson, but the young Horry had decided he was going to be a math teacher.

“My mom was a teacher, my aunt, my great aunt, there were so many people on my mother’s side that were teachers,” he said. “So I just thought, ‘Hey, they’re making decent livings out of that, so that’s the way to go. That’s the way to make a good, clean living.”

As a child, Robert became fascinated with money. His father would give him the change in his pockets, and he would sell rides on his go-cart for a quarter. “He’s always been a person who could handle himself financially,” said his mother. “When he had an allowance, you couldn’t get that money out of him to save your life.”

Often times, the young boy would just sit on his bed and count his pennies, count his nickels, count his dimes, and count his quarters. All the while, a fondness for counting, adding and subtracting of numbers began to grow, and his favorite class became mathematics.

In high school, the student-athlete even tutored several of his fellow classmates in arithmetic. School came easy to Horry. So much so that he seldom had to bring home a book. But he did bring home that basketball.

When his junior year rolled around, the Bulldogs led by Horry and his best friend, point guard Derrick Trawick, were expected to compete for the state championship. Only, Trawick had been dealing with some personal problems and committed suicide on campus one day.

“It was real tough, especially for me because I had just spoken to him,” Horry remembered. “I told him I’d be right back and, as I was walking through the gym, I heard a gunshot go off. When I came back out, there he was laying on the ground. I thought it was a car backfire, by the time I got back, people were crying, and they were keeping everybody away.

“It’s things like that that make you think about life and how wonderful it is. You know you’ve got to respect people you love while they’re here and really appreciate them, because life is so precious.”

Although the loss of his closest friend was extremely tough on Robert, he continued to take care of business on the court. As a senior, he averaged 25.9 points and 10 boards and was named the Naismith Alabama High School Player of the Year, not to mention a Parade, McDonald’s, and Converse All-American. In four years, he had led Andalusia High to a 90-22 record and two appearances in the state tournament.

Upon graduating, the 17-year-old decided to go to the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, even though his first choice was Georgia Tech, so he could live in between his parents. “My mom, she said, ‘If you don’t go to Alabama, I won’t come to see you,’” he explained with a chuckle. “Woop, I’m going to Alabama.”

The choice was a good one.

Despite beginning his freshman season on the bench, Horry was promoted to starter for the Crimson Tide after one of his teammates was injured. From then on, the position was his. “Robert was a guy that made an impact on our program right away,” said then-assistant and current ‘Bama head coach Dave Hobbs. “Some publication early on was rating all these people and players coming into college that particular year. They said the most overrated player in that class was Robert Horry.

“Robert’s kind of a real easy-going guy off the court, but at the same time, he is tremendously competitive. So I think that kind of stoked some competitive fire in Robert and, really, he achieved from the moment he walked in here.”

Horry didn’t just walk in, he jumped, he ran, he dove for four years. Teaming with current NBA players Latrell Sprewell, David Benoit, Keith Askins, and Jason Caffey at one point or another, Alabama went 98-36 in Robert’s time there and made two swings through the Sweet 16.

His senior season he joined LSU’s Shaquille O’Neal as the only players in the history of the Southeast Conference to block more than 100 field-goal attempts in a year. And he was named first-team All-SEC, All-SEC Defense, and All-SEC Academic.

It seems the publication that called him overrated, underrated him. But so, too, did the residents of Houston, who laughed, booed, and jeered their hometown Rockets when Horry was selected with the 11th overall pick in the 1992 NBA Draft.

Hoping for a shooter to complement the inside games of Hakeem Olajuwon and Otis Thorpe, fans had come out in droves to the Rockets’ Draft Party, anxious to see who their team would choose. Although there was some disagreement as to who they should take, everyone knew it would be either Harold Miner out of Southern California or UCLA’s Tracy Murray.

“HOW COULD THEY?” the headline the next day in the Houston Post best expressed the feelings of anger and betrayal that the fans showed as they quickly rushed out of the building in disgust after the team chose Horry instead.

The team stuck behind their new small forward though, at least for the first year. But in season two, despite rookie numbers better than 10 points and five boards, Horry was packaged with journeyman Matt Bullard and a pair of second-round picks and given a one-way ticket to Detroit for swingman Sean Elliott.

A return ticket would have to be purchased days later, though, as Houston avoided the trade when Elliott failed his physical due to a kidney disorder. Horry and Bullard were in the Pistons’ locker room suiting up for the first time for a game against New Jersey when they heard the news.

“They were like, ‘We’re happy you’re back, yadda, yadda, yadda,’ all that old B.S.,” he said of the reception he received when he returned to Texas. “But for me, I was like, ‘Don’t even sweat it, it’s all business, just go and do your daily routine and just go on with your life like it was.’”

For the next year or so, Horry told reporters that the Pistons jersey he never wore was hanging on his bedroom wall as a reminder and an inspiration. “Well, you know, I told people that story, but it’s not really hanging, it’s sitting on the floor,” he admitted. “I think it was the first time in history that guys were traded, were going to walk out on the court, and then were not allowed to. And then they had to go back to their old team. So I figured I’d keep it, maybe it will be worth something one day.”

The return of Robert was worth a lot more to Houston than they realized at the time. His 38 percent shooting from the three-point arc and his defense at both forward positions played a big role in the Rockets’ defeat of the New York Knicks in the 1994 NBA Finals. So big, Horry often said after the championship run that his teammates wouldn’t be wearing rings if it weren’t for the voided trade.

“Not any disrespect to Sean Elliott, but there’s a lot of things that I can do that I don’t think Sean can do,” he clarified. “I was able to guard (Charles) Oakley and (Anthony) Mason and Charles Smith, and I don’t think Sean would’ve been able to guard them—not because of his athletic ability—but just because of his height. You know, height makes a big difference when you’re guarding people like that.

“People always say, ‘You should be happy you were on the team.’ But they should be happy I came back. That’s the way I look at it.”

The Rockets may have been even happier with their forward the following year when time came to defend their title. After barely escaping Utah and Phoenix in the opening two rounds, Houston blasted San Antonio, setting up a return to the Finals where Orlando awaited.

While Shaquille O’Neal and Penny Hardaway held their own against Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler, the Magic had no answer for Horry, who was dominating as he averaged nearly 18 points and four assists to go with his 10 rebounds a game. He set an NBA Finals record with seven steals in Game 2 and another record for his 11 three-pointers in a four-game series—one of which he drilled in the closing moments of Game 3 for the win.

“We won the world championship twice,” Olajuwon said. “He was the key. He played a key role in making it happen.

“Playing with Robert was so much fun for me, and that will be something in my memory for a lifetime. He’s an excellent player, he can feed the post, he can finish so strong on fastbreaks, and he can hit the threes.”

Although he was a member of two championship teams with the Rockets, four years of feeding the Dream down low or shooting threes when Hakeem was double-teamed began to wear old. Horry was ready to move on when the Suns made the trade for him and teammates Chucky Brown, Mark Bryant, and Sam Cassell.

“Just like in a regular job, sometimes it just gets monotonous, everything gets redundant,” he said. “I felt, for me and the Rockets, it was time for a change. I’m not a person who cares about shooting the ball a lot, I just like to touch it every once in a while to see if it’s still around.”

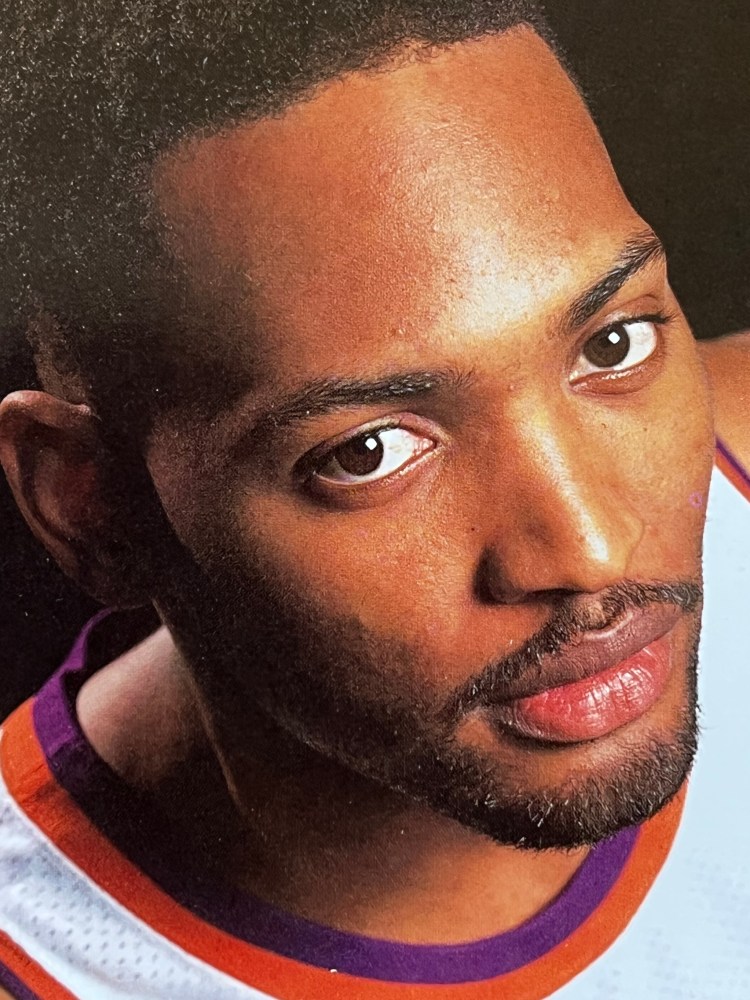

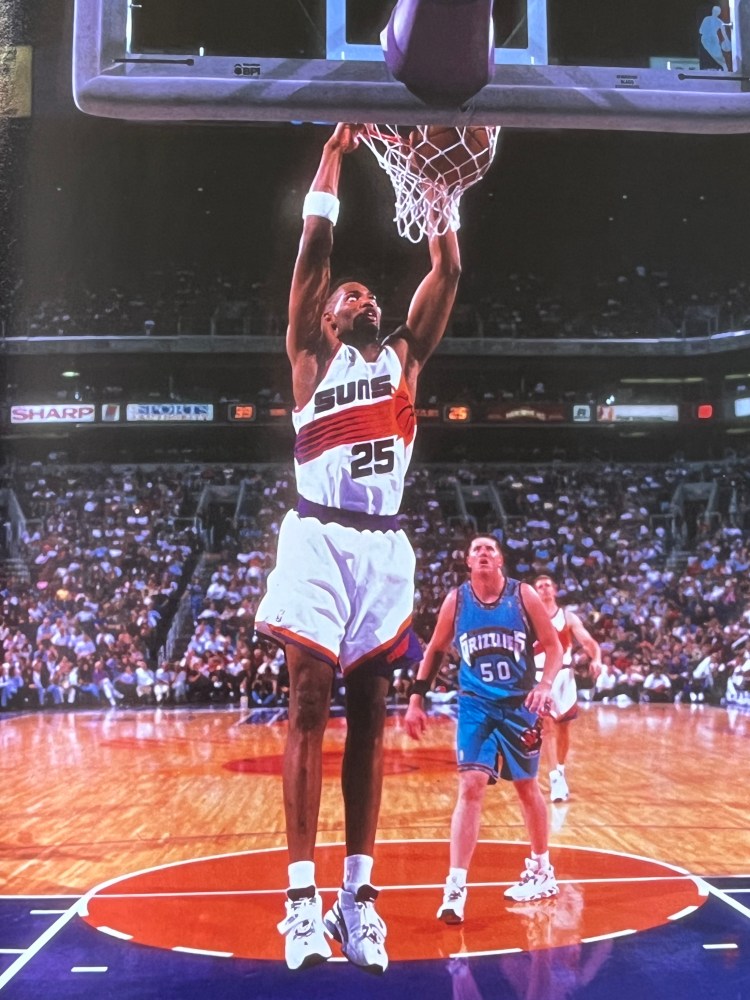

Well, since pulling on his number 25 Suns jersey, Horry’s touched the ball more than ever. And although he’s struggled a bit in adjusting to his new team and new role early on, Cassell warns that his best friend’s time will come.

“Robert is a helluva ballplayer,” he said. “A complete team player, he can do it all. If he can work on his ballhandling just a little bit, he’ll be a bona fide all-star.”

If only the kids in Andalusia could’ve seen the future, maybe Robert Horry would’ve been picked to play once in a while.