[Entering the 1991 NBA draft, the Orlando Magic had two first-round draft choices, numbers 10 and 23. When the first pick came around, the Magic played it conservatively. They grabbed Brian Williams (later Bison Dele), the then-seemingly steady, level-headed power forward from the University of Maryland. For their second pick, Orlando went out on a big limb. They took a high-risk, potentially high-payoff chance on seven-footer Stanley Roberts, who’d played one season each at LSU and then in Spain.

When Roberts arrived in Orlando several months later above his recommended playing weight, risk seemed to have overwhelmed any possible payoff. Magic GM Pat Williams quipped, “Stanley Roberts’ idea of a balanced meal is a Big Mac in each hand.” Magic coach Matt Goukas rued, “I’ve seen a lot of guys come to camp in my 26 years in the NBA, but none have been this bad out of shape.”

The two articles below track Roberts’ rookie season in Orlando. The first, from the December 1991 issue of Magic Magazine, takes a mostly upbeat view of Roberts’ early season woes, smashed backboards included. The second, from the May 1992 issue of the same publication, recounts his late season rise. The bylines for both belong to writer Bill Doughty, who does a nice job in communicating the facts.

Roberts lasted one season in Orlando. Williams and Goukas, bothered by Roberts’ battle of the bulge, traded him to the Los Angeles Clippers before the 1992-93 season. The trade prompted the quip, “Stanley’s so big, when he left Orlando, it left two roster openings.” Ironically, the Clippers had considered drafting Roberts the year before, but passed because he reminded its brain trust of Benoit Benjamin. “Both were drafted largely on potential,” explained a Clippers beat reporter. “Teams hoped they would grow out of problems with weight and lack of motivation. Both are still trying to do so.” Another publication noted, “Big Stanley may give new meaning to the phrase: shoulda, coulda, woulda.” The point being, under the right circumstances, Roberts had the talent to succeed in the NBA. He was a hig- payoff talent.

Technically, Mr. Shoulda, Coulda, Woulda spent eight seasons in the NBA, spanning 1991 to 2000 but with a few gaps in between. However, Roberts was on the floor for 14 games or less in three of those eight seasons. His final averages read: 8.5 points, 1.3 blocks, 5.2 rebounds per game.]

****

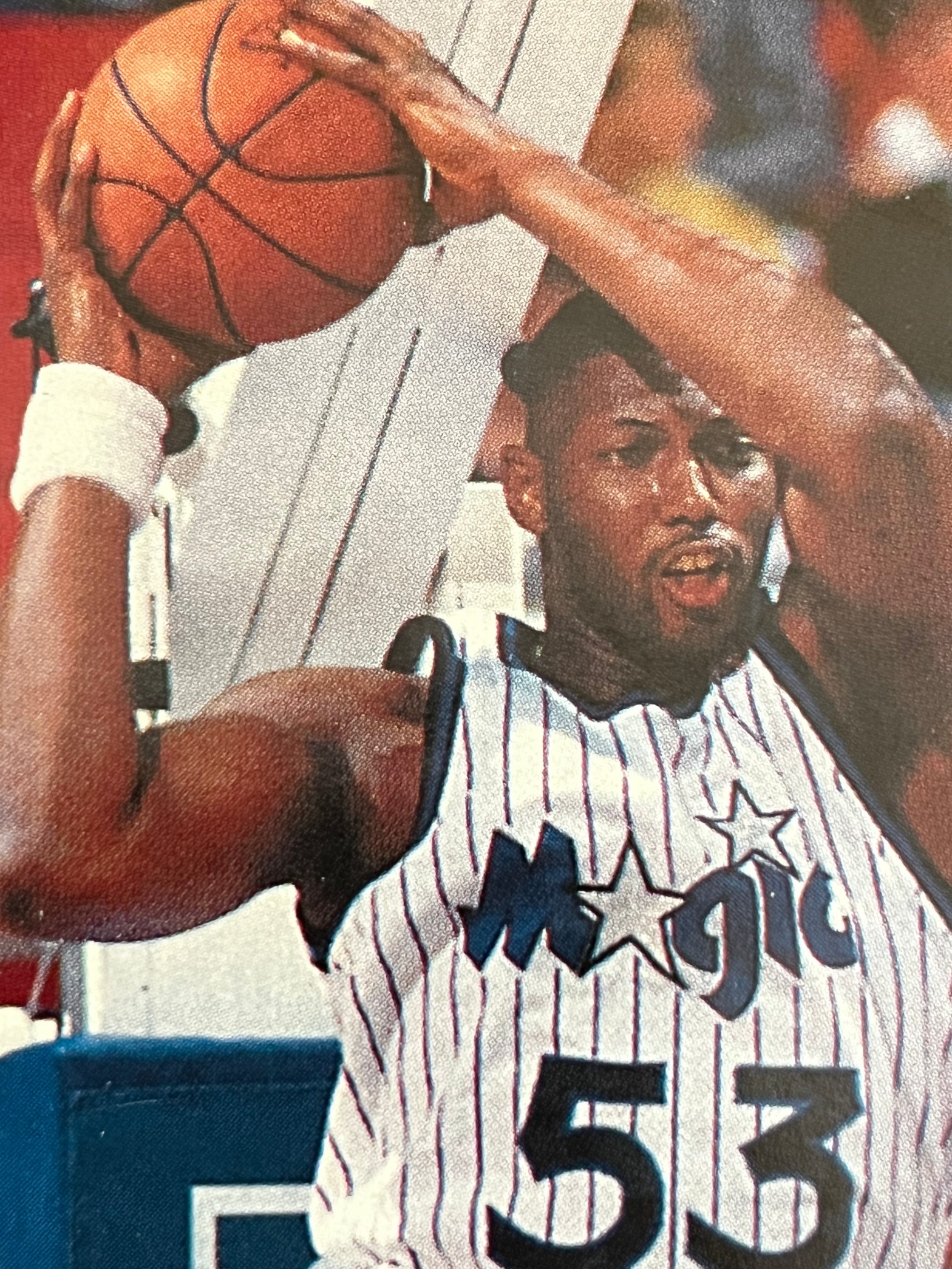

When the Orlando Magic drafted Stanley Roberts with the 23rd selection in the 1991 NBA draft, they were hoping the seven-foot center would make a big impression. Unfortunately, the biggest impression he has made in the early season has been on the rims at the Magic practice facility.

The oft-maligned but vastly promising. Roberts came into training camp in disappointing, but not entirely unexpected, condition. His inability to get himself well below the 300-pound mark has left the 21-year-old rookie sitting at the end of coach Matt Guokas’ bench, where he’s trying to learn the NBA from afar. Still, he believes he can become a force to be reckoned with in this league.

Observers at an early November practice session got a good look at the kind of power Roberts possesses. At the downtown Orlando Recreation Center, where the Magic conduct practices, Roberts shattered not one, but both glass backboards, bringing that day’s session to a premature close.

Thunderous dunks, however, are about the only attribute Roberts has been able to display in the early going.

When the Magic drafted him, they knew they were getting a very large question mark. Roberts flunked out at Louisiana State University, played one professional season in Spain, and has shown an inability to push himself away from the dinner table. When Roberts appeared in Orlando the day after the draft, he admitted that he had “dug himself a hole,” and vowed he would do everything necessary to become a bona fide NBA player. That would include, he said, coming to Orlando in July—with or without a contract—to begin conditioning workouts.

It didn’t happen. Weighing a reported 310 pounds on draft day, he showed up for camp a day late and several pounds heavier. “I spent the summer at LSU playing in pick-up games. My agent [Oscar Schoenfelt] didn’t want me to come to town without a contract and get hurt or something,” Roberts said of his non-appearance.

As for his condition, he said he hired a personal trainer only two weeks before camp opened. “My agent was thinking in terms of me working out a little into camp; he wasn’t going to bring me in until the middle of training camp to give me a little time to work out with the trainer and get in better shape,” Roberts said. ”Unfortunately, we came to terms on the contract, and I ended up here earlier than expected and was a little more out of shape than I wanted.”

As a result, Roberts—who inked a one-year deal worth a reported $500,000—lagged far behind the rest of the team, literally unable to keep up throughout the preseason. Nevertheless, there was a glimmer of hope when he made his debut against Detroit in the preseason opener. Roberts tallied 10 points, hitting 3-of-5 field-goal attempts and 4-of-4 from the free-throw stripe to go with eight rebounds and two blocked shots. He finished the exhibition season averaging 5.3 points, 4.4 rebounds, and 14.4 minutes a game.

But he suffered a slight knee injury in practice, and his playing time dwindled as the regular season approached. Guokas preferred to go with what he knew in the pivot. “I know what Greg Kite and Mark Acres can do,” he said at the end of the preseason. “Stanley has yet to show me what he can do consistently. The time for experimentation is over.”

He sat out the Magic’s season open-opening win over New York. When Greg Kite missed the second game against Philadelphia due to the death of his father, Guokas gave Roberts the starting nod. Orlando fell behind 10-2 in the first two minutes, Guokas sat Roberts back down and kept him there the rest of the game as the Magic rallied for the victory.

An NBA rookie’s lot is never an easy one, and Roberts expected a tough time. He acknowledges that his lack of conditioning has put him further behind. But despite Guokas’ lack of faith, Roberts fully believes he can be an impact player once he gets his bearings.

“The NBA is rough, tough, and fast-paced; I love it,” Roberts said. “Right now, I feel a little tight. The first couple of weeks were really hard, because I was out of shape. But now that the regular season is here and I’m getting into condition, I think I can contribute.”

As with most first-year players, Roberts finds the level of competition greater than he could imagine. “Night after night, you’re going up against top-flight players. In college and in Europe, you might play a great player one night and an average one the next. But at this level, everyone is great or they wouldn’t be here.”

Being about two steps slow on defense, he has displayed an unhealthy propensity for fouling. He attributed that again to his conditioning, and the fact that “rookie’s don’t get the calls.”

“I think I can be effective,” Roberts maintains. “I think I can really help the team defensively as a stopper in the middle. Offensively, I can help by crashing the boards; I want to make things happen.”

He’ll have to bide his time for now, Guokas said. “Stanley will get his chances, and he’ll have to make the most of them,” the coach said. “He’s got a lot to prove.”

As the season opened, Roberts’ weight was headed in the right direction: He was reported to be under 300 pounds. Team officials believe his best weight would be in the vicinity of 270, however, so he still has a ways to go. Then it will be up to him to prove he can be the player who helped lead LSU into the NCAA playoffs two years ago and the Real Madrid team to the finals of the European tournaments last season.

Roberts has yet to demonstrate that without a doubt he belongs in the NBA. He has a year to erase those doubts. If all goes well, pretty soon he will be bringing down the house instead of just the backboard.

[And now the second article. It comes five months later and looks retrospectively at the better half of Roberts’ rookie season. Writer Bill Doughty picks up the story.]

When the Orlando Magic announced they were selecting center Stanley Roberts with the 23rd pick in the 1991 NBA draft, the fans, players, and staff held their collective breath. They knew they were getting a player possessing tremendous physical tools and almost unlimited potential. But they also knew there was a big question mark about whether Roberts possessed the inner discipline to turn that potential into reality.

The question was valid. The seven-foot Roberts had been a Proposition 48 casualty coming out of high school and sat out his freshman year at LSU. Teamed with Shaquille O’Neal and Chris Jackson, he was expected to take the Tigers to NCAA finals, but instead the team was torn apart by infighting among its three stars. Roberts fell short in the classroom, flunking out and opting for pro ball in Spain. There, he was sometimes petulant off the court and inconsistent on it. His weight ballooned to a pre-draft of 310 pounds. Yet his size and physical abilities were too great for the Magic to pass up. They took a gamble.

The early season did little to dispel those pre-draft fears. Roberts was a week late reporting for camp, holding out in a contract dispute. Despite promises that he would work-out over the summer, his weight was still above the 300-pound mark and his conditioning was awful. He languished on the bench once the season began, playing only sporadically. When he did get on the floor, his lack of conditioning and frequent foul problems ensured that his stay was a short one.

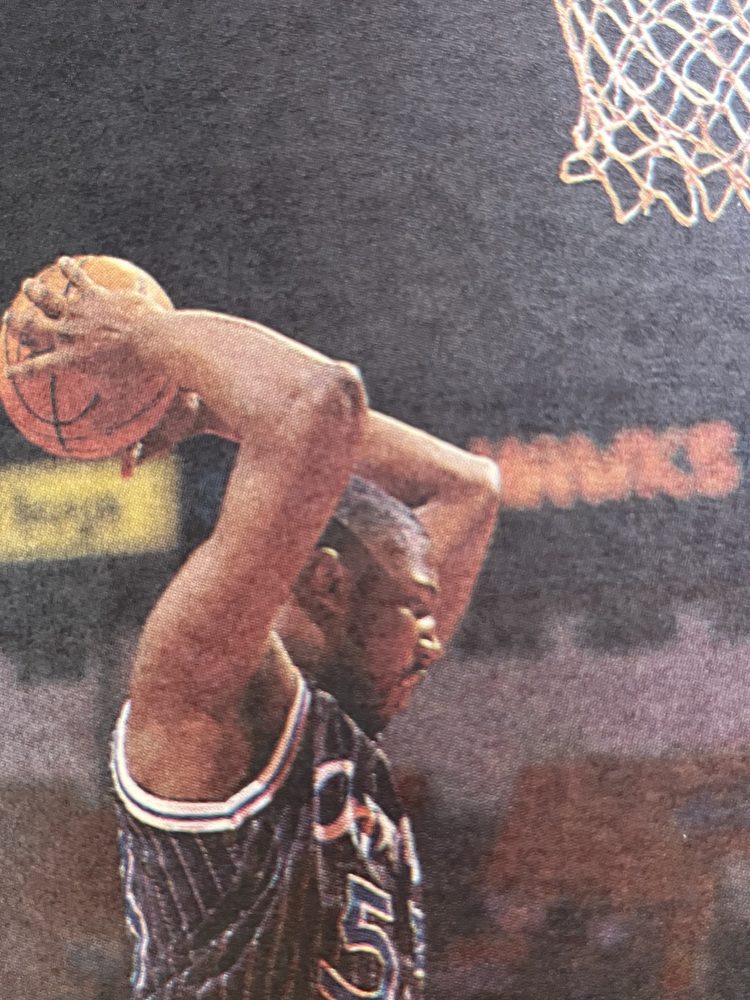

But slowly, Roberts came around. A turning point occurred in early February when he scored 23 points and grabbed nine rebounds in a win over Minnesota. He followed that with 24 points, nine rebounds, and seven blocked shots against Atlanta the next night.

Until an ankle injury at the end of March finished the year for him, Roberts had become a starter, averaging 10.4 points and 6.1 rebounds. While he’s no threat for Rookie of the Year honors, it has been a satisfying freshman season.

“I think he came in amongst a lot of watchful eyes; there was some doubt,” guard Sam Vincent said. “I thought he handled the situation very well. I think he did a lot more than was expected.”

General manager Pat Williams agreed. “I think he had a good rookie year. He’s played hard and made a lot of progress.”

Although coach Matt Goukas was more cautious in his evaluation, he also agreed that Roberts has done surprisingly well for his initial season. “He had a good stretch in the middle of the season, where he got a lot of playing time—at least as much as his conditioning and foul problems would allow,” Goukas said. “Quite frankly, going into the season I didn’t think he’d get that much. We saw enough of him to see some of the good things he’s capable of, some things we can work on in the off-season, if he’s willing.

Roberts’ game combines the brute force that his size implies with a surprisingly deft shooting touch for one so large. He complements his rebounding and shot-blocking capabilities with a scorer’s mentality. “What I really like about Stanley is that he knows how to score,” forward Terry Catledge said. “He’s got soft hands, a soft touch around the basket; he can shoot off the glass. He just has to learn not to get in foul trouble. Teams go at him knowing that he’s going to try and block shots. He’s just got to be more mature on the defensive end.”

For his part, Roberts said he’s had to focus on every game. “Every night you’re going out and playing the best there is, Patrick [Ewing], Hakeem [Olajuwon], David Robinson, Robert Parish, Moses Malone,” Roberts said. “It’s not like college, where you could take a night off here and there and not work as hard.”

Of course, making it in the NBA means making adjustments not only on the court, but off it as well. Thanks in part to his year in Europe, Roberts has had an easier time with the transition than most rookies.

“We traveled a lot in Spain, but it’s not like the NBA, where you play a game, fly out the next day, and have to be ready to play again that night,” Roberts said. “You just have to adjust, get your rest, and be ready to play.”

“There’s been a lot coming at him,” said Catledge. “In the past three, four months, I think he’s really matured, not only on the court, but off—getting the proper rest, eating properly, being focused for each game. That’s what it takes.”

Roberts credits his teammates for helping make that transition on and off the court. He already was good friends with Jerry Reynolds, a fellow LSU alumnus, coming into the season. Catledge is friends with Roberts’ fiancé. Roberts played with Dennis Scott at the Nike summer camp when they were in high school.

“The team has stood behind me the whole season, from the beginning with my weight and conditioning problems. They told me not to worry about what people were saying,” Roberts said. “Greg Kite was a great help. He’s been around so long, playing against Parish and all the big centers. He would sit down with me before games and tell me about stopping a particular player. Nick Anderson lives in the same apartment complex as me; he’s helped me a lot off the court. I hang with Sam Vincent. They’ve all played a big part.”

Becoming a father had a lot to do with the maturation process, too. Roberts has a four-month-old daughter and is engaged to her mother, a nursing student at South Alabama. Roberts met her when she was a student at Southern University in Baton Rouge, where LSU is located.

Roberts is a long way from his hometown of Hopkins, S.C., where he grew up with an older brother and younger sister. As a youngster, he didn’t have much interest in basketball or sports in general. He played in eighth grade at the behest of the coach, who obviously couldn’t resist the allure of the large 14-year-old. But Roberts didn’t really like playing and quit as a ninth grader. Instead, he found his sport in the streets, where he admits he was possibly headed for big-time trouble.

“In the 10th grade, the coach coaxed me out, told me I probably wouldn’t make the team, but that I could scrimmage with them,” Roberts said. “My brother had just gotten through playing for him and a couple of my uncles had played, so I went out and ended up making the varsity.”

Roberts led Lower Richland High School to two state championships, was a three-time all-state selection and twice selected as South Carolina Prep Player of the Year. As a senior, averaging 25.2 points and 9.8 rebounds, he was named to the Parade All-American team.

“My guidance as a youngster came primarily from my high school coach, I spent most of my time with him,” Roberts said. In the evening after practice, he would go to the coach’s home, where he would have dinner and study. “Coach definitely pulled me off the path I was on. If it wasn’t for him, I don’t know where I’d be today.”

Roberts went on to LSU, but things never did go right there. “Stuff happened,” he said. “Coach [Dale] Brown did everything he could. I messed up a few times. The chemistry was never right on that team; there was conflict between Shaquille and Chris, conflict between me and Chris, conflict between Coach Brown and Chris. Because of my grades, I would have had to sit out another year if I’d stayed in school. So I made the decision to leave. Luckily, things have worked out.”

His teammates dubbed him “Big Friendly.” It’s an apt nickname for the open, easy-going 22-year-old who, despite any problems he may have, rarely gets down on himself. “Stanley’s fun to be around, always bustin’ jokes,” Catledge said. “He comes in every day the same, you don’t see him down on himself. I like having him for teammate.”

“Even when I do get down, I try to smile. You never know what’s going to happen, so you just have to keep a good outlook,” Roberts said.

Guokas is perhaps slightly less appreciative of Roberts’ humor at times, but agrees that he’s a team player. “It’s probably as much a curse as a blessing,” the coach said of the center’s laid-back manner. “You’d like everybody to be friendly, easy-going off the court, but on the floor, you like to see everybody be a tiger with a vicious attitude out there. To survive, to do well, succeed and win, you have to be on a mission. You can’t be Mr. Nice Guy out there.”

Still, that even temperament is beneficial as Roberts travels the rocky road facing all players in the first few years, Guokas said. “It’s important that he doesn’t get down on himself, but also that we don’t get down on him either. We can’t expect miracles overnight. It’s going to take some time.”

Most everyone connected with the Magic agrees that the most important season for Roberts will be the offseason. Will he keep the weight off and work himself into even better condition? Perhaps the lessons learned during the early part of the season at the hands of personal trainer David Oliver of Orlando Sports Medicine Center will serve as incentive for Roberts not to let himself go.

“It was awful,” he said of those sessions. “I was going through two workouts a day plus games. I’m not worried, though. I know what I’m capable of. I’m going to stay in shape. I’m looking forward to getting back, starting off good this time.”

It could be the most interesting summer for Roberts, who was headed for a vacation in Spain at the end of the season. Depending on the outcome for the draft lottery, Roberts could find himself reunited with O’Neal. Though “the Shaq” has said he doesn’t want to play in Orlando and was reported to have said that he and Roberts couldn’t play together, Roberts would welcome the reunion.

“Me and Shaq did okay together. It was just the situation. I can understand where he’s coming from, though. He just doesn’t want to come in and have conflict,” Roberts said. “I’d like to see him here. If he comes out and does better than me, I’ll play behind him, that’s fine. I’m comfortable starting or coming off the bench; I can play both roles. It’s going to be a battle, though, I can tell you that.”

Magic fans also will have to wait and see how Roberts’ contract situation plays out. After his holdout earlier this year, he inked a one-year deal worth an estimated $500,000. He becomes a restricted free agent this summer, and you can bet he’ll probably command a much better deal, either from another team signing him to an offer sheet or from Orlando, which has the right to match any offers.

“That’s all up to Pat Williams,” Roberts said. “When the offer sheets come in, and if I see Pat’s not going to move on an offer given to me, then I might have to leave. I don’t want to leave. I think I found a home here. The fans love me, and I love being here. But if the situation calls for me to leave, I’ll have to find a new home. I’ve got no choice.”

Yes, it’s clear Stanley Roberts has answered a lot of questions. Now he wants his due. And how does he want the fans to remember his rookie year?

“I want them to remember the second half,” he laughs, adjusting his injured ankle in the whirlpool. But then he thinks for a moment. “I’d like them to remember the first half, too, because next year is going to be totally different. I want them to see how I’ve changed. I want to get all the stuff about my weight and my conditioning—what I can do and can’t do—behind me.

“When they first drafted me, some people told me I couldn’t play in this league, that I didn’t have the discipline. I think I’ve pretty much proved them wrong.”