[Today, it’s not uncommon for NBA teams to divide playing time between two talented big men. But in the early days of the NBA, that wasn’t the case. Teams built their championship hopes around finding that rare dominant big man. No Mikan, Wilt, Russell, or Abdul-Jabbar; no championship. Or so it was thought.

This hard-and-fast law of the NBA jungle finally softened when the Golden State Warriors improbably won the 1975 NBA championship without that one great seven-footer policing the paint. The Warriors did it by using two good, but not great, centers interchangeably. This two-headed monster—one muscular and strong, the other tall, thin, and athletic—stayed energized for 48 minutes. They also gave coach Al Attles greater flexibility in the middle, depending on the night’s matchup down low and his style of play.

The following article, from the November 1975 issue of Hoop Magazine, spells out this innovation brought to you by the Warriors’ Al Attles, who really deserves more credit as one of the NBA coaching greats. John Morgan, then writing for the San Mateo (Calif.) Times, tells the story.]

****

Avid students of the National Basketball Association learned something about the New Math during the 1974-75 season. It was that 1 + 1 = 1.

It’s a highly unlikely piece of arithmetical deduction provided by the Warriors of Golden State.

Through a combination of fortuitous factors, it was Golden State’s good fortune to be able to overturn, at least for the moment, a time-honored hallmark of NBA reasoning. In the process, the Warriors went to the head of the class.

Golden State has bucked a tradition, which seemed to have the strength of both logic and pragmatic evidence behind it. By using their two centers interchangeably, the Warriors captured the 1975 NBA championship and established themselves as contenders for the future.

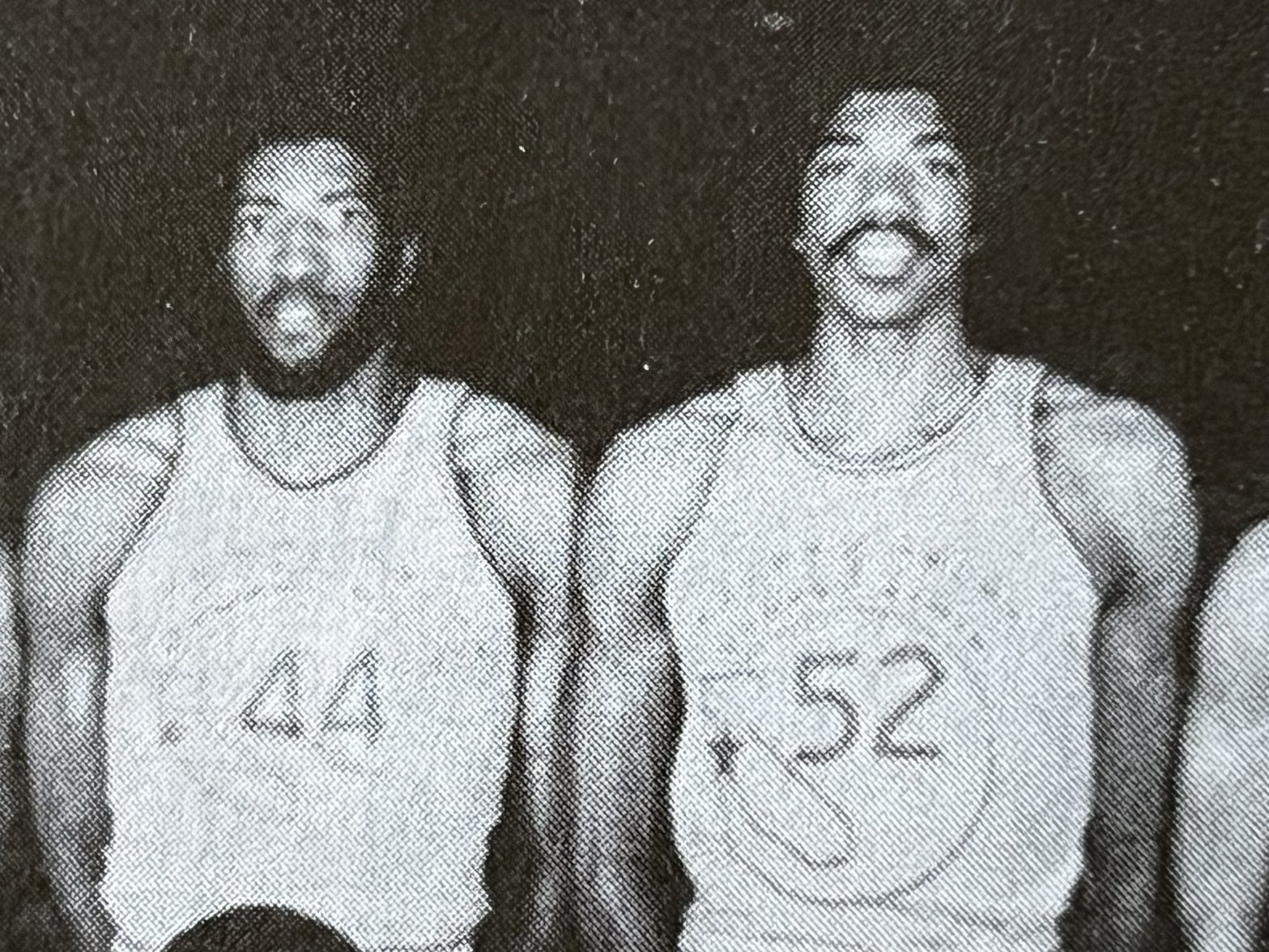

This utilization of two equally gifted centers—Clifford Ray and George Johnson—flew in the face of an accepted theory, which states infallibly that you cannot win such a crown without that single dominating man in the middle.

But the Warriors established that two are better than one. They shattered such thinking in 99 illuminating basketball games, the last four of which swept them past Washington’s Bullets in the league’s final playoff series.

The effectiveness of their strategy persists today. Still, there is a certain irony in all this: those two big man, Ray and Johnson, are from Tweedledee and Tweedledum. They are, in fact, dissimilar. They are really the NBA’s own version of the Odd Couple.

Ray, a bachelor, is 6-foot-9, 235 pounds. His is a physical game. He intimidates enemy drivers with his grim visage, savage aggressiveness, and overpowering strength.

Johnson, married and the father of a baby daughter, is 6-foot-11, 205 pounds. He relies on grace, timing, and leaping ability as he plies his delicate craft. Johnson’s is a game of finesse.

The Oscar Madison-Felix Ungar analogy is an apt one. Their styles are as different as their television counterparts. And their ratings have lately soared just about as high. “In many respects,” says Warrior coach Al Attles, “they are opposites. Clifford is obviously stronger. He’s better working the pick-and-roll. He screens out better on the defensive board. But George is quicker on the offensive board. If you put their skills into one player, you’d have one tremendous center.”

As it is, Attles has gotten remarkable mileage out of this iconoclastic arrangement. Taken as a combination, Ray and Johnson, who will both turn 27 this season, collected 1,444 rebounds, 476 of which were offensive, during the 1974-75 regular season. Neither man missed a game. Those rebounding totals would have led the NBA in both categories had they been compiled by one individual.

In addition, the Warrior duo blocked 252 shots between them, again the top total in the league. They scored at a 13.8 point-per-game clip, shooting 50 percent from the floor and 61 percent from the free-throw line.

In 17 playoff games, they shot 55 percent from the field, 60 percent from the line, for 11.3 points per game. They retrieved 292 rebounds, 109 of which were offensive, and they blocked 61 shots.

“They keep people off balance,” Attles points out. “When one of them comes out, the other changes the tempo. Other teams can’t concentrate on just one style of play.”

“When I watch George from the bench,” says Ray, “I believe that he is now as dominating as any center in this league. He has gained confidence and experience. With that knowledge, he has a tremendous future ahead of him.”

“I’m not as physical as Cliff,” notes Johnson. “He can muscle people more than I can. Cliff is extremely strong defensively. Both of us need to work on our offense.”

The two centers came to Golden State via slightly different routes. Johnson, who was cut by Chicago in training camp after being drafted in round five by the Bulls out of Dillard University in New Orleans, got a tryout with the Warriors in the summer of 1972 after being spotted in a semipro league that year. He impressed Attles enough to secure a roster spot.

Ray, another Chicago draftee (round three in 1971 out of Oklahoma), found himself wearing the livery of the Warriors in 1974 after being traded to Golden State for the great Nate Thurmond.

It is noteworthy that in the showdown for the league’s Western Conference championship last season, those Chicago castoffs proved to be critically important against the same Bulls. That series went seven games and, in the last one, a fresh Johnson came off the bench to block four Chicago shots in the final two-and-a-half minutes to seal the victory for Golden State.

The concept of keeping rested bodies in a contest at all times was an Attles’ trademark throughout the 1974-75 season. And the center position, perhaps embodied that theory more than any other. “Playing the full 48 minutes can take its toll,” explains Attles. “Right from the start, I had it in my mind to play them equally.”

“By substituting like that,” says Johnson, “both of us can play hard. We could do more. That position was always at full strength. We saw some of those other centers getting tired in the playoffs. Our strategy was hard on our opponents. It really had an effect. You could see it, especially in the second half of most games.”

Ray agrees. “Having two men at center made us just that much tougher,” he says. “George and I complement each other. In practice, I work hard against him. I’ll be playing against centers like George, and I concentrate on playing him and learning. George has established that he can block shots. Other players are aware of that. For that reason, they won’t drive on him as much. They know he can reject their shots. That knowledge in itself is worth a lot.”

There is a further ingredient in the Ray-Johnson mix: a sense of togetherness. Their competitive relationship has not been marred by jealousy or petty backbiting. “They have a genuine respect and liking for each other,” says Attles. “They root for each other constantly.”

This is one Odd Couple that seems likely to endure.