[In the early 1960s, Boston Celtics’ publicist Bill Mokray worked with Pyramid Books to put out an annual 40-cent paperback that profiled two dozen or so of the pro and college game’s top stars. This humble paperback came with Mokray’s boastful bio in the front. In the 1964 edition, Mokray’s self-written bio included a recent achievement: “As vice president of promotion for the Boston Celtics, he was the one who single-handedly completed arrangements for the Cousy Day program and, despite his absence that day, the festivities went off so smoothly that no one thought of giving him public commendation for a job well done. It wasn’t the first time he’s been overlooked in his many years of service to the game!”

Mokray took his grievance a step further by adding a final chapter to Basketball Stars of 1964 that describes Cousy’s final trip around the NBA, including Cousy Day, a.k.a., the Cooz’s final home game in Boston Garden on March 16, 1963. He slugged the chapter: “We Love You, Cooz!”]

****

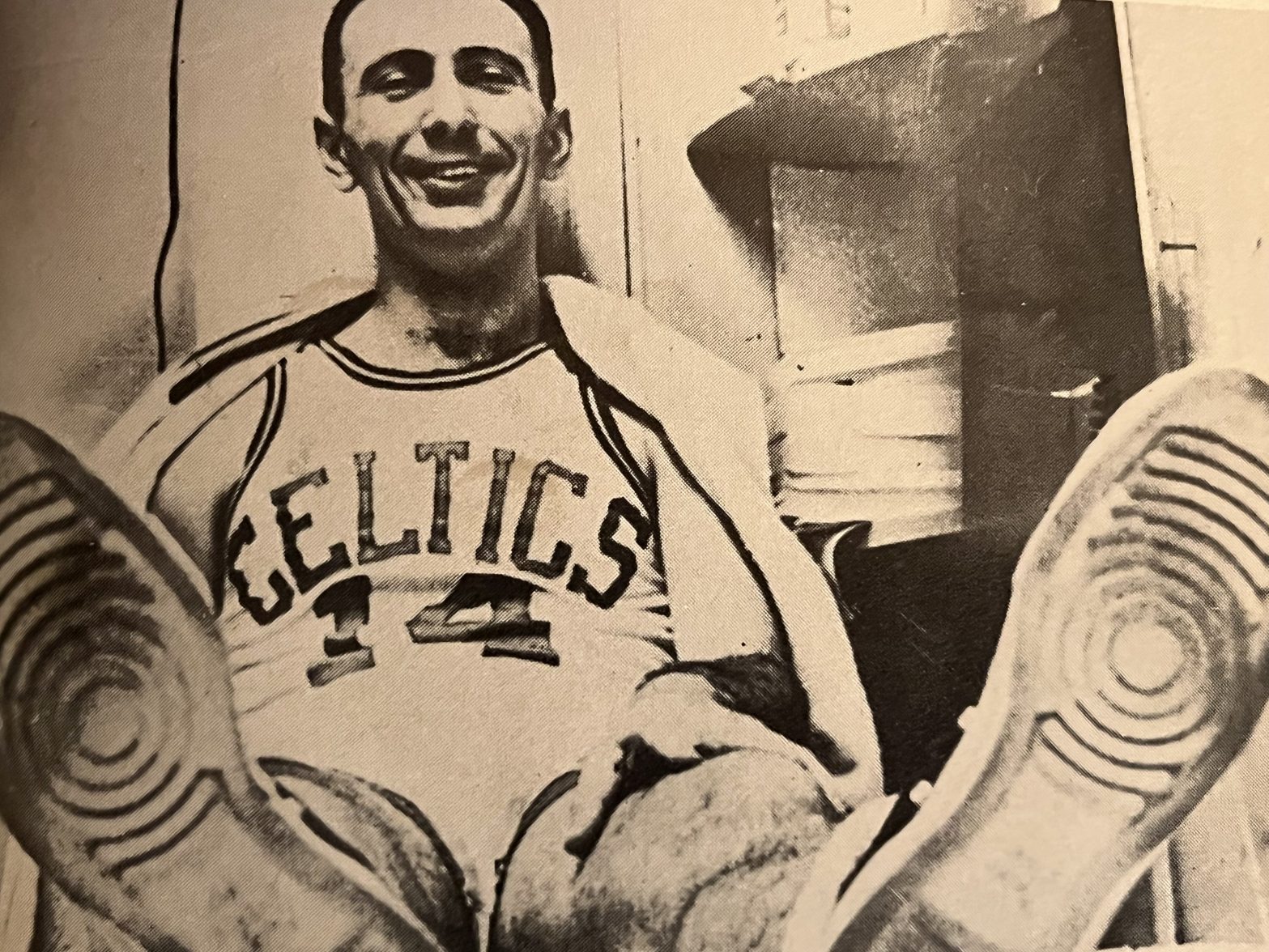

Any opus on current basketball idols would be incomplete without some reference to Bob Cousy and the memorable day held in his honor last March. So many thousands of words have been written on his exploits, and countless millions have seen him perform on television screens or in person that it will be rather trite to view his many heroic feats here.

There was a certain magnetism and showmanship to this superlative athlete, which inspired many columnist to hail him as the “Babe Ruth of Basketball.” Like the lovable Bambino, Bob did perform many acts of charity, which may never be known.

Before the 1962-63 season even got under way, the Boston Celtics captain publicly announced that this would be his final NBA season. Thus, as the world champions made their last visit to rival cities, each team paid its respects to the fellow who had given Class to the league—class with a capital C. Until he came on the scene 13 seasons ago, the play-for-pay game was almost like a traveling tent show with most teams playing a stereotyped pattern and a club or two folding at the close of every season.

When the Celtics made their final appearance in St. Louis last February, Cousy’s old nemesis, Slater Martin came up from Texas just to present him with a silver service set on behalf of the Hawk management. At Los Angeles, the Lakers and the local Holy Cross alumni club [where Cousy attended college] presented him with a plaque and typewriter, plus color movies of the presentation. Syracuse, Providence, San Francisco, and Chicago likewise came up with suitable and sundry awards.

One of the finer gestures was made by [Holy Cross] Crusader alumni of Detroit and the Pistons’ millionaire owner, Fred Zollner. In Bob’s name, they announced that they would give a four-year scholarship at Holy Cross to some deserving school boy from Michigan.

The same reception awaited the Celtics captain at Madison Square Garden, where in spite of the newspaper strike in New York, an unbelievable crowd of 14,195 came out to honor a local boy who had made good in a real big way.

But the program that topped all programs was the one right in Robert’s own stamping grounds, the Boston Garden, where he had captured the hearts of the local populace. He had made basketball what it is in New England today through 17 years of basketball magic—the first four years at Holy Cross, the next 13 as the inspiring hero of the “New York Yankees of Basketball.”

There seemed to be a novel touch to this Cousy farewell. One could not have improved upon it if he had spent years in the planning. Bob’s final home game came on March 17; what would be more fitting than St. Patrick’s Day in Irish Boston? The opponents happened to be their archrivals, the Syracuse Nationals. A one-man committee worked silently on the festivities for two months to see that the entire program clicked on a dignified level. All presentations were of sentimental—not material—value to the guest of honor. Bob confided to his intimates that he would have preferred not to have the day.

The game, which had no bearing on the final standings, was sold out 12 days in advance. A special 52-page program reviewing Bob’s career via pictures and biographic copy, had a 6,500-copy run, and it was gobbled up before game time. Mail orders alone totaled 1,200, and even 5,000 extra copies had to be reorded and since have become a collector’s item.

Bob’s parents, who rarely saw him perform, came up from St. Albans, New York, for the event. There were numerous fans from distant points. To please those unable to purchase tickets, the game was televised throughout New England—after one of the national networks declined to take it gratis.

The pregame ceremonies caused almost everyone to cry—including those sitting before their TV screens and the taxed assembly of the North Station Depot. This inspired the Boston Record- American’s John Gilloley to refer to the occasion as the Boston Tear Party. Among the afternoon’s highlights were the following:

–A set of gold cuff links with 14 (Cousy’s famous number) and an album of letters from youngsters at his summer camp

–Sunday missals to the Cousy girls—11-year-old Marie Colette and Mary Patricia, 10, from 12-year-old Martha Grady of Arlington, Massachusetts, in behalf of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, of which Bob is national chairman.

–A sterling silver cigarette case from the wives of the Celtics players, presented by Mrs. Rose Russell.

–A sterling silver cigar humidor from the Celtics players, presented by Frank Ramsey, second oldest Celtic player in line of service.

–A plaque from the Academy of Sports Editors, representing 100 of the nation’s largest dailies, in recognition of Bob being voted the NBA’s all-time no. 1 star.

–A color pastel of Mrs. Cousy, a personal gift of Ned Irish, president of the New York Knickerbockers.

–Ten plaques, 18 by 23 inches, featuring the greatest photographs and newspaper drawings of Bob, covering his 35 years, presented by Maurice Podoloff, NBA president, in behalf of the league. Another NBA gift included a tape recording and colored movies of the entire program.

–A color pastel of the Cousy children, given by the Boston basketball scribes through Joe Looney.

–A set of Syracuse china by members of the Nationals. This presentation, quite appropriately, was made by the game’s ironman, Dolph Schayes. He won the plaudits of Hub fans by hailing the guest of honor as Bob O’Cousy and himself as O’Schayes. He brought down the house a second time by saluting him with an “Erin go Braugh” and “masel tov.”

–Walter A. Brown and Lou Pieri, co-owners of the team, presented a sterling silver service set, while both Mayor John Collins of Boston and Governor Endicott Peabody gave the traditional Paul Revere Bowls and citation.

The afternoon was finally topped off with a letter from President John F. Kennedy, commending the all-time great for his basketball prowess and making himself such a hero to the youth of the nation.

Luckily, the guest of honor had written out his sentiments in advance, but he failed miserably in trying to hold back a flood of tears. Two nights earlier, he clocked his acceptance speech at seven minutes. This time, it took 20, as he courageously tried his best to limp through it or was repeatedly interrupted by his legion of admirers. At one point, little Marie extended her father, a handkerchief.

An unscheduled highlight of the entire program occurred during one lull when Bob just could not continue. At this very psychological moment, far from the depths of the balcony, came a booming voice: “We love you, Cooz!” It was subsequently identified as that of Joe Dillon, a Cousy admirer from years back. The 13,909 assembly cheered lustily. With that assist, the Celtics captain finally control his emotions and managed to struggle through his last lines.

Everything thereafter was incidental. Few knew or really cared as to how the game would come out. There was a humorous twist to the last four minutes of the contest. When Bob was removed, everyone stood up and cheered—totally oblivious to what was transpiring out on the court. In the opinion of veteran sportswriters, this program must go down in sports annals as memorable as the one held in honor of Lou Gehrig in Yankee Stadium more than two decades ago.

The Celtics did participate thereafter in 13 playoff games, and they made no secret that they wanted to win all the marbles just so that their veteran captain would retire as a champion. It tickled their hearts that they succeeded in copping the deciding game right on the home court of the Los Angeles Lakers, their strongest challengers.

And, just as Hollywood would wish to write the script, if it ever should decide to do the life of Bob Cousy in celluloid, the Cooz was the hero. Midway through the game, he turned his ankle and had to be helped off the floor. And then, just when the Lakers threatened to overtake their rivals to force a seventh game, out came the Boston idol.

The severe pain in his ankle, miraculously gone, he insisted on going back into the lineup. He was himself as he held his club together in a spine-tingling finish to win 112-109. The Cooz was bouncing the ball at midcourt in his inimitable style just as the final buzzer sounded. With that, he heaved the ball sky-high and fell into the embrace of Bill Russell.

With the excitement of the triumph over, Bob’s first remarks were: “God was good to me.“

So ended the basketball career of Bob Cousy, the game’s greatest magician of all time.