[The first toot comes from Bill Mokray’s Basketball Stars 1964. Terry Dischinger, the reigning NBA Rookie of the Year, is listed among the league’s marquee names, including Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Oscar Robertson, Elgin Baylor, and Jerry West. Dischinger wouldn’t keep this elite company for long. Time would tell that Dischinger, an athletic, 6-foot-7 swingman with a knockdown jump shot, wasn’t nearly as talented as the NBA’s other superstars. His career also was hamstrung by some bad luck. He landed on too many losing teams (mostly in Detroit), got yanked around by too many “new” coaches, battled chronic health problems, and interrupted his NBA service for two years of military service.

Nevertheless, Dischinger was a solid pro for nine NBA seasons. He retired with a career average of 13.8 points per game, shooting 50 percent from the field and 75 percent from the charity stripe). Back then, Dischinger also very much in the conversation in his native Indiana for being one of the basketball-crazed state’s all-time greats. A cerebral type, Dischinger spent his post-NBA career in the Portland, Oregon area as a successful orthodontist. Dischinger passed away in October 2023 at the age of 82 and likely with few regrets. “It was kind of a storybook thing,” Dischinger reflected on his basketball career. “Just like being on the Olympic team—I know that happened, I was part of it, but it still seems a little bit like a fairy tale.”

Let’s revisit Dischinger’s fairy tale. Let’s revisit that once upon a time when this tall, skinny kid from Terre Haute was considered one of the NBA’s finest.]

****

Anytime that Terry Dischinger flashed a hot hand in a high school or college basketball game, opponents used to refer to him as “Terrible Terry. Judging by the manner that he crashed into the NBA ranks last season to win Rookie of the Year honors, the nickname will stick with him through his pro career.

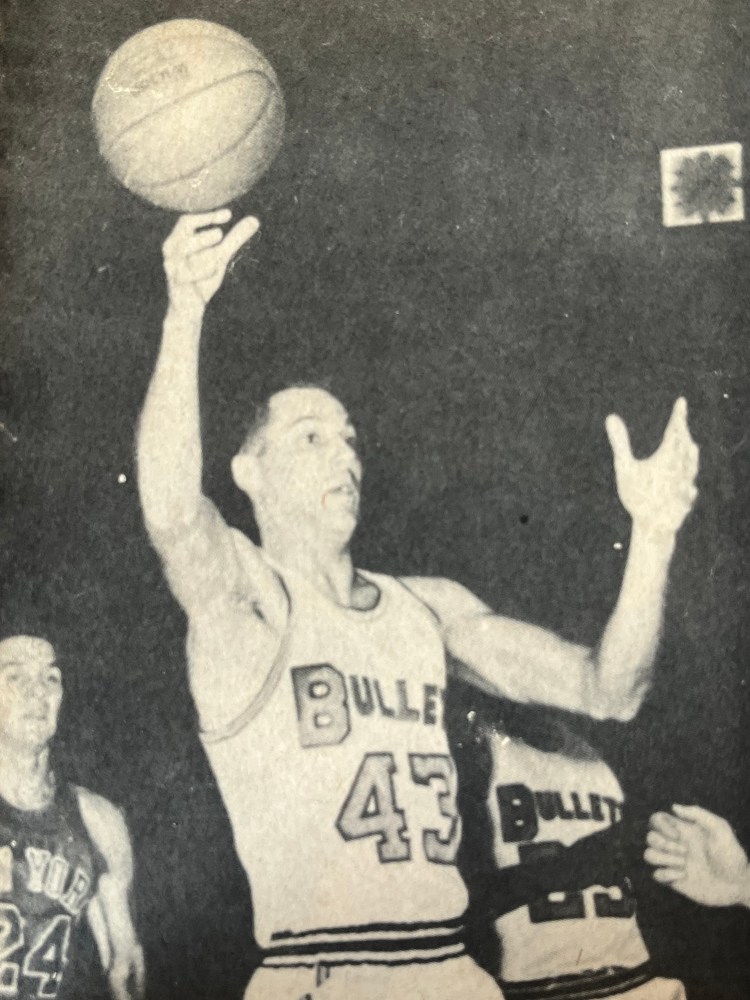

Since the close of last season, the Chicago Zephyrs moved to Baltimore, where they are now known as the Bullets. Hoop fans in the Chesapeake area are going to take this star to heart. In the one-time Purdue All-America luminary, they have a shooting demon good enough to cavort regularly for any of the other clubs.

Few, if any, were surprised at the way Terry walked off with rookie honors last winter. What impressed the hardened sports experts was the manner in which he compiled his brilliant record. Even though he missed more than a quarter of the season’s 80 games, he still finished as the 14th highest in league scoring and seventh best in scoring average.

A study of the season’s statistics showed that he was the fourth highest in floor shooting marksmanship. Had he connected on only 12 more of his 1,016 shots, he would have won top honors in that department of play and thus would have become but the third rookie to gain such honors. The only two newcomers to perform that trick were Alex Groza in 1949-50 and Walter Bellamy in 1961-62.

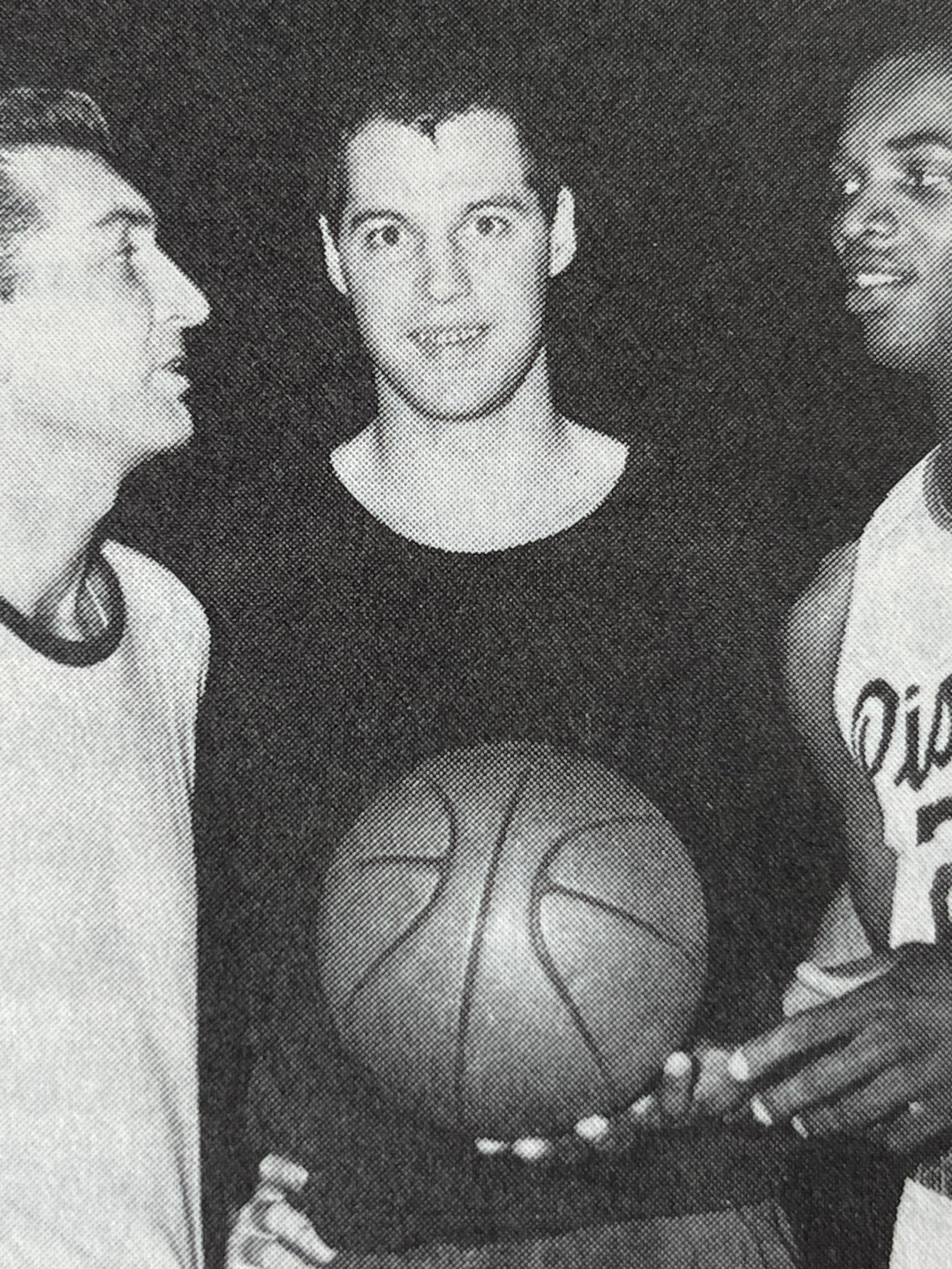

Terrible Terry was the Zephyrs’ second-round draft choice back in 1962. Few doubted his ability to make the NBA grade, even though he carried but 195 pounds on his 6-foot-7 frame. What scared all the clubs was the report that the Purdue scoring ace was seriously planning on playing AAU ball after graduation. Indeed, the rumors were well-founded for he was employed by the Phillips Oilers during the summer of 1962.

However, that did not discourage Frank Lane, the one-time Big Ten whistle-tooter who subsequently made quite a name for himself as a baseball general manager. No sooner was he appointed business manager of the Zephyrs than he resolved that he would sign the Boilermaker. Five times he made a trip to Lafayette, Indiana, to try to induce Terry to sign with the pros, and each time he failed. However, on his sixth visit and sixth new offer, “Trader Lane” hit the jackpot.

Frank proposed a unique arrangement, whereby the hoopster would play for the Windy City club during the winter and apply his chemical engineering knowledge in the offseason in the laboratory of a nationally known Chicago bakery. Besides, since he was still pursuing his studies at Purdue toward his undergraduate degree, he would perform for the Zephyrs only on weekends or any time he felt such appearances would not interfere with his classroom work.

“And do you know what?” explained Lane in gloating over his salesmanship, “Terry asked that—until he joined the team on a full-time basis in late January—we could pay him on a per game basis. In other words, if he played fewer games than we anticipated, we would not have to pay him. Now, how can you beat a fellow like that for honesty!”

“Disch” then kept in condition throughout his part-time activity by working out daily in the Purdue gym.

The NBA coaches and writers paid high tribute to Terry’s periodic appearances by naming him for the annual all-star game in Los Angeles last January 16. He was the only first-year man to qualify for the classic—and this in a season, which everyone declared was especially rich in talent. Even though he managed to get into the game for only seven minutes and scored seven points, he was so tickled with the honor that before the various players departed for their next games, he had each autograph his souvenir program booklet.

“Now look at this,” whispered Freddy Schaus, coach of the West team, to a reporter as the rookie sought his signature. “What an unassuming kid. Bet he’ll treasure this souvenir more than anything he ever got in college!

If a rival coach, like Schaus, thinks so highly of the newcomer, imagine how much his own coach, Bob Leonard, values him. A respected playmaker of a national championship Indiana team in his day, Bob can spot a star a mile away. “This Dischinger is no flash in the pan,” says Leonard. “He is going to become a superstar as soon as he familiarizes himself with the moves of his opponents and tailors his game to the way certain referees have the tendency to make the calls.”

This might seem hard to believe, but 15 years ago when Clyde Lovellette was performing for Garfield High School in Terre Haute, Indiana, he was the idol of two little boys, Bobby Kehrt, the son of the basketball coach, and Terry Dischinger, the offspring of the football mentor. Every now and then, when hoop practice was over, Big Clyde would indulge in playful games with the two small fries, who could not run home fast enough to tell their mothers.

Terry’s basketball career actually started in the basement of his home. It was there that he and Bobby spent countless hours perfecting their marksmanship on a miniature court. Just about the time that “Young Disch” seemed to show signs of his future greatness, he had to quit altogether. By the time he attained his 11thbirthday, he was 6 feet tall. His growth had been so rapid that he developed a heart murmur. Doctors advised his parents that his condition was not too serious and, in time, he would be normal and would be in a position to resume his athletic activities.

The serious fellow had been in the habit of coming out first in anything that he undertakes. For instance, when he graduated from Garfield in 1958, he was 6 feet 6 ½ and placed first in scholarship in a class of 129. He made all-state honors in both basketball and football. He was a good first baseman. He placed third in the high hurdles and second in the low hurdles in the 1958 state high school track meet. A good all-around four-letter man!

For a while, Terry was undecided about his future. Should he go into the ministry or take up dentistry, he asked himself. He finally decided that he wanted to become a chemical engineer and enrolled at Purdue. If his dad, Donas Dischinger, was disappointed that the boy hadn’t enrolled at Indiana, his alma mater, Coach Willard Kehrt, the Hoosiers’ hoop co-captain, was in a position to console him since his Bobby likewise enrolled at the Lafayette campus. The inseparable athletes ended up as roommates.

Terry’s varsity career had barely got off the ground when the entire college basketball world was aware of his feats. His first three conference games—against Indiana, Wisconsin, and Illinois—he posted a 34.3 point per game average. In his first season, he set a new campus standard for most points (384) in conference play, as well as (605) for a complete season. When he was congratulated for his superlative 43-point performance against Illinois in a return meeting, he was far from the happy chap one would expect him to be. “Thanks a lot,” he graciously acknowledged the felicitations, then dejectedly added, “What good was it—we lost.”

Before he hung up his shoes, he also poured in 52 points against Michigan State, an all-time Big Ten record. It was not surprising that the sharpshooter was named to the 1960 United States Olympic basketball team. To help prepare himself for the Rome games, he did considerable running and shooting. He also found time to work in the packing department of a Terre Haute plastic concern so he could return with souvenirs for his family. Despite the limited service he saw in the Olympics because of the wealth of material Coach Pete Newell had, he still emerged as the fourth-leading scorer.

It might be worth recalling that eight future NBA stars represented this nation at Rome – Jerry Lucas, Oscar Robertson, Walt Bellamy, Jerry West, Bob Boozer, Darrall Imhoff, Adrian Smith, and “Terrible” Terry—quite a club, possibly strong enough to give those Boston Celtics quite a run for the world title.

Among his many campus feats, Terry tossed 24 consecutive free throws against Notre Dame in the Hoosier Classic in Indianapolis. Of the hundreds of excellent hoopsters who have cavorted in the Big Ten since its founding in 1905-06, Terry was the third ever to win the conference scoring crown in all three varsity seasons. The other two were the late Hall of Famer John Schommer, University of Illinois, 1909, and Don Schlundt, Indiana, 1955.

Terry, though, went even further. His 1961-62 production of 559 points and 32.8 point per game average were the highest in the entire history of that circuit! His successive varsity totals of 605, 548, and 726 still stand as the highest in Purdue history.

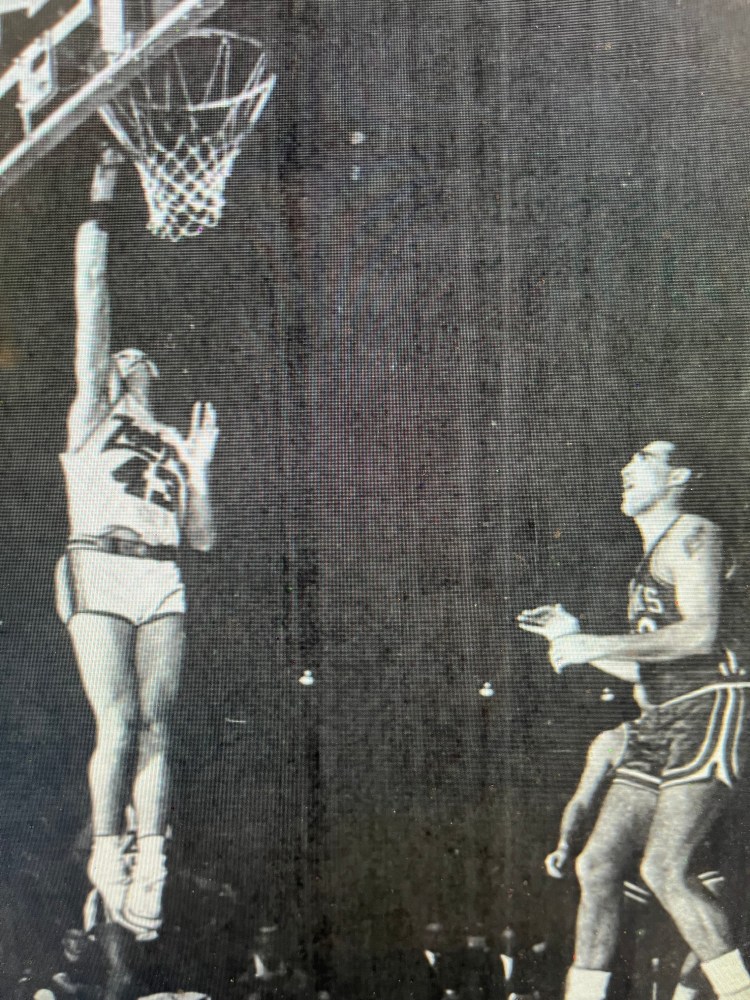

An indication of what a clever artist he is look at the way he performed against Los Angeles last winter. “That boy amazes me with every game he plays,” says Leonard. “Only the other night, Baylor, LaRusso, and West took turns trying to stop him. I was surprised in the manner he analyzed each fellow’s defensive weakness.

“Against Elgin, he uncorked some quick jumpers. He drove on Rudy, and he hooked over Jerry. I did not have to tell him to do any of this—he simply figured it out all by himself.”

Since he no longer has to worry about classroom work, Terry should have another great year and become a popular favorite in Baltimore. Unlike baseball, these NBA players don’t seem to have any of this “sophomore jinx.”

The Zephyrs (or Bullets) were not as weak as last winter’s 25-55 record would tend to suggest. The team was only 4.1 points weaker than its opposition in the 82-game schedule. Sixteen of its losses were by the margin of three or fewer points. A break here and there, and the Zephyrs could well have won half of those contests. With the new season, a new locale, new home fans, new uniforms, Terry is all primed to write some new records.

[Bill Mokray was right. Dischinger didn’t battle through a sophomore jinx in Baltimore. However, he did navigate some bumps that came with his switch to the backcourt. The bumps mostly dropped his name from the NBA’s honor roll of rising superstars. They also earned him a one-way ticket out of Baltimore and onto the struggling Detroit Pistons. What follows is a more irreverent, but fun, toot about Dischinger in season three. It comes from the Detroit Free Press’ great Jack Saylor. His piece ran in the newspaper on December 16, 1964.]

Terry Dischinger has suffered a setback.

The sharp-shooting Piston still leads the NBA in field-goal percentage, but he no longer leads the league in dirty sneakers. It’s like this. The palms of Dischinger’s hands perspire freely and to combat this, he used a sticky, resin-type substance on his hands. For handy use, he kept an abundant supply of the brown gook stocked on the inside of his otherwise white footwear.

Result: Dirty shoes, dry hands, accurate shots. But there came a directive from the league office—cease and desist. So, Dischinger will make the adjustment. “I think it just got to be a habit, anyway,” he laughed.

He has made a far more important adjustment in switching from the frontcourt positions he has played all his life to guard. He made it in stride, that’s because this pleasant, highly intelligent, 24-year-old knows who he is. His basketball plans are mapped, and his off-court future, likewise, is well charted.

“I have another year left on the contract I signed when I started in Chicago,” he explained. “Then I’ll play on a year-to-year basis after that.”

Dischinger put education foremost, even after embarking on his pro basketball career. He was only a weekend warrior with the Chicago Zephyrs until he completed his bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering at Purdue.

“I’m starting back to school again at Purdue this summer,” he said. “I hope to get a doctor’s degree in industrial economics. I might like to go into college teaching, and you need a doctor’s degree to be a professor. If not, it’ll still get me a much better job if I go in the industry.”

Married and the father of two little ones, he is vitally concerned with his future. The accent on education follows naturally for Dischinger, the senior class valedictorian at Garfield High in Terre Haute, Ind. This, in addition to being a four-sport star, made Terry quite an All-American boy. As a Hoosier, basketball was his first love, and All-American boy he was for three great years at Purdue.

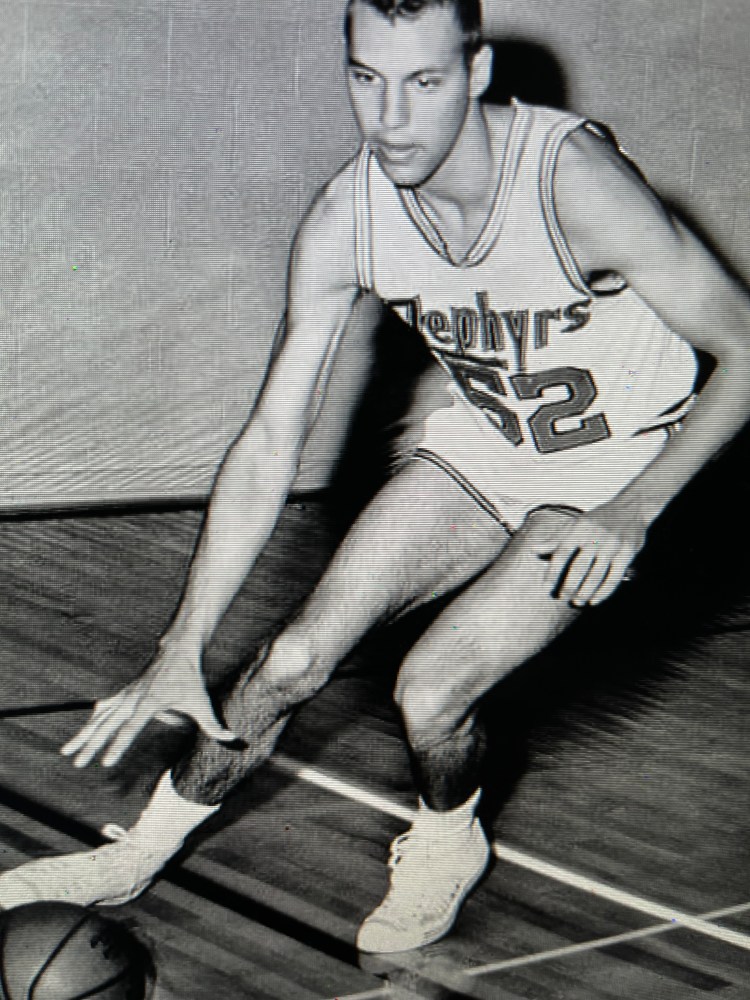

He made the 1960 Olympic team as a sophomore and won the Big Ten scoring title three straight years. All of this was done in the forecourt—and was little different with the pros. Although playing only 57 games, Dischinger averaged 25.5 points with the lowly Zephyrs and was named Rookie of the Year.

The club moved to Baltimore and problems developed. One of the finest shooters in the game, Dischinger weighed only 190 pounds and was being pushed around on defense and while rebounding.

Bob Leonard, then the Bullet coach, wanted to try him at guard, but it left only Gus Johnson with scoring punch upfront. “Slick (Leonard) got down on me,” Disch recalled. “He didn’t think I played good enough defense, and Rod (Thorn), Si Green, and Kevin Loughery were playing guard, so I spent more time on the bench.”

Still, he again made the all-star team and averaged 20.8 points. His offseason trade to the Detroit Pistons ensued, and Operation Big Switch was completed in Detroit. “When you break in as a forward and have some success, they’re not anxious to change you,” Terry pointed out. “But with Dave (DeBusschere) and Ray (Scott), we were strong at forward, and they felt I could do the job at guard.”

Dischinger analyzes the switch the way you would expect of a graduate engineer. “For my weight, I’m better fitted to play guard than forward,” he said. “I don’t have to battle bigger guys on the boards, and it doesn’t take as much out of me. I think my effectiveness over an entire game is increased by playing guard.”

Dischinger, at 6-6 ½, always has been one of the fastest men in the league. “In high school, I ran the high hurdles in 14.9 seconds and the lows in 19.8,” he said. “I worked on speed a lot then.”

The word from Baltimore was that Dischinger lacked stamina. In Detroit, he has become a veritable Iron Man—and it’s not all because of the move to guard. “I worked all summer doing isometrics,” he explained, “and I feel stronger. I’ve got a lot more wind, and my stamina seems to have improved. I can go harder at both ends of the court than before and don’t have to pace myself like I did before.

“I reported this fall at 218 pounds—and that was too much,” he added. “But I’m at 205 now, and I feel strong.”

With the surplus weight and learning to adapt his fantastic offensive moves to a guard position, Dischinger got off to a slow start. There also were new problems in ballhandling and learning to guard smaller men. But Terry has come on fast, and chances for a third straight all-star berth are extremely good.

“I’ve been on the all-star team and been rookie of the year, and anybody who says it doesn’t give them great satisfaction isn’t telling the truth,” Dischinger said. “But if your team doesn’t win, it’s not much fun at all. That’s the main thing—to be a winner.”

Dischinger hasn’t had great luck in that respect—even at Purdue. ”Ohio State was in the league, too,” he quipped. His 1960 Olympic team was a winner, though—and making the team as a sophomore gave Disch his biggest thrill.

“Not the basketball itself—the closest game was something like 30 points,” he said. “But just being there and being part of it . . . playing for your country made it a little bit different.”

The Piston star’s biggest fault is probably his reluctance to shoot more. “It’s a question of breaking old habits,” he says. “If I miss a few, I quit shooting. I’m trying to overcome this, but I try not to take bad shots. I’m still learning the moves at guard. I think as the season progresses, I’ll get more shots.”

The Pistons are hoping so—his shooting is just their Disch . . . with or without dirty shoes.

[Dischinger finished his third NBA season as one of the go-to guys in Detroit, knocking down a team-leading 18.2 points per game. He also appeared in his third-straight NBA All-Star Game in 1965. Then Uncle Sam called. “He had been an ROTC student at Purdue,” explained Detroit journalist Jerry Green. “And now his number came up in the summer of 1965, as America was just starting to become serious in a military way in a country named Vietnam.” Dischinger would miss the next two NBA seasons. When he returned to NBA action for the 1967-68 season, he did so as a part-time roll player, no longer the go-to guy.]