[Say Shareef Abdur-Rahim fast three times, and your tongue might get twisted. But there’s nothing twisted about this name and its higher meaning—“noble” (Shareef) “servant of the most merciful one”(Adbur-Rahim). Neither is there anything twisted about the former NBA star of the name same name who has spent his life doing good and serving others.

This brief article, published on October 21, 1999, paints an inspiring picture of Abdur-Rahim doing good while entering his fourth NBA season with the then-Vancouver Grizzlies. There would be 12 NBA seasons in all for Abdur-Rahim, who retired in 2008 with career averages of 18.1 points, 7.5 rebounds, and 2.5 assists per game. Today, Abdur-Rahim is president of the NBA Development League.

Howard Tsumura, a reporter with the British Columbia newspaper The Province, is at the keyboard. Tsumura now runs a fantastic site called Varsity Letters, which covers prep and college sports in BC. Give it a visit, but first, let’s take a look back at an outdoor basketball in Atlanta, and Tsumura will tell us more.]

****

One shoveled away the earth. The other poured the concrete. Together, William Abdur-Rahim and his eldest son Shareef put up a basketball goal.

Ten years later, the goal is still there, as William and Shareef discovered this past summer. They were riding around Atlanta, looking at poverty-stricken areas and talking, William recalls. “It was like 2:30 in the morning, and we were still driving. Then Shareef says, ‘Let’s go see if the goal is still there.’ So we went, and when we turned in, the lights would shine directly on the driveway. And sure enough, there it was, just as strong and straight as ever. We were laughing. We said, ‘We put cement down in that ground, down in the hole, and that pole is not going anywhere.’”

Nothing better symbolizes the essence of Vancouver Grizzlies All-Everything Shareef Abdur-Rahim than his first basketball hoop, the one he first dunked on at age 13. Its foundation is unshakable. It remains deeply rooted in its community. It has weathered many storms.

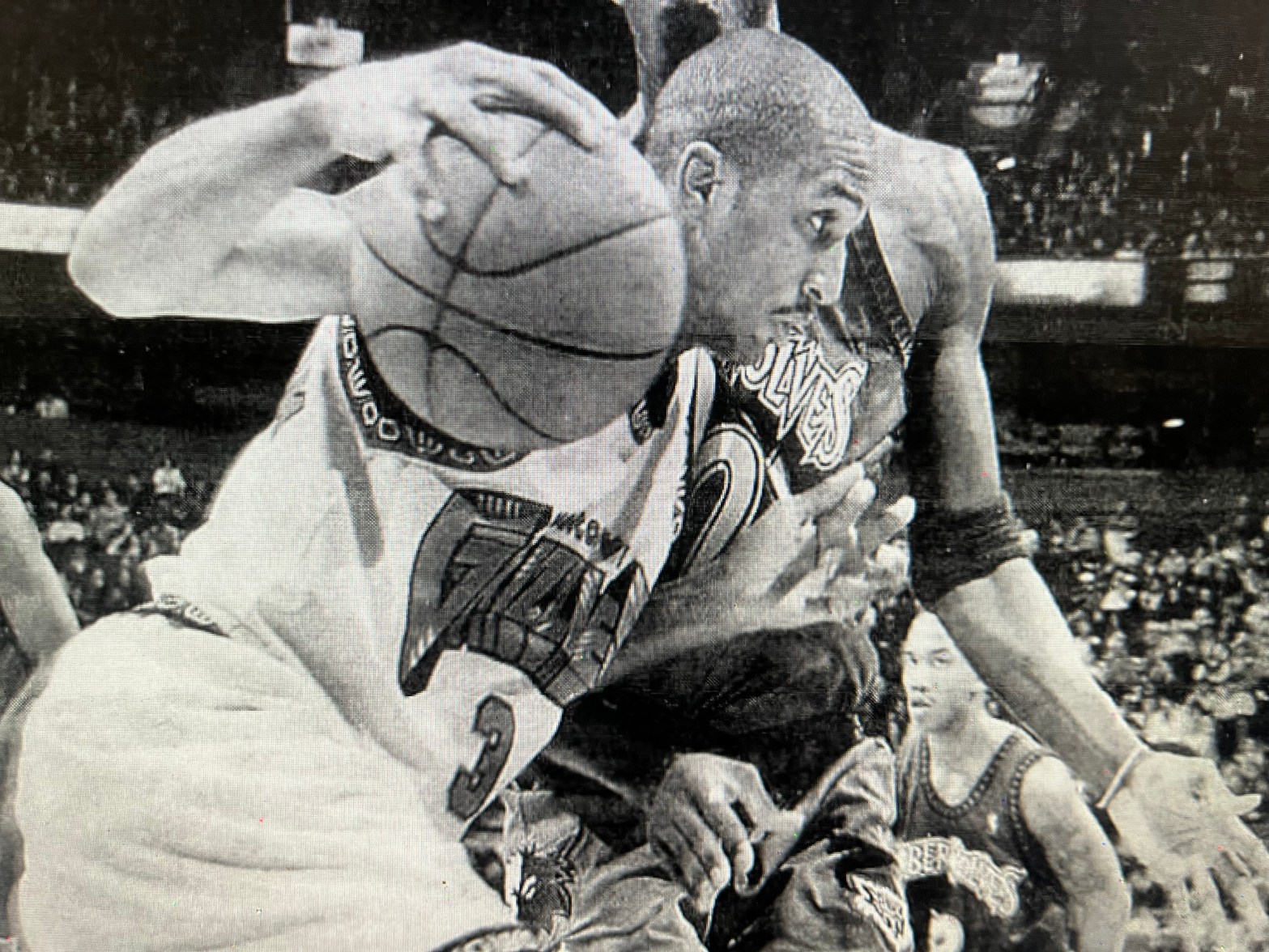

Shareef Abdur-Rahim begins his fourth NBA season on Tuesday as one of the league’s acknowledged stars. But to define him, simply by his oncourt accomplishments is to overlook his quest for social justice and his commitment to helping the underprivileged.

“It doesn’t really have anything to do with me as a basketball player,” Shareef says. “If I was a doctor or a lawyer or wasn’t even a so-called ‘successful person,’ I think I would still try to do good in my own way.”

For William, seeing the old hoop that night reaffirmed how driven Shareef was to succeed in life, to take his childhood lessons and apply them to his adulthood. “It reminded me of when he was in the seventh grade and we lived in that house, and he was this long, lanky, wide-eyed kid,” he says. “You could tell he was on a mission. He could have been a farmer. He could have been a bus driver. It didn’t matter. His plan was not to drop the ball.”

He hasn’t. But he also avoided running into the spotlight. “He has been raised to shun seeking the camera or seeking the glamour,” William says. “He doesn’t want to toot his own horn.”

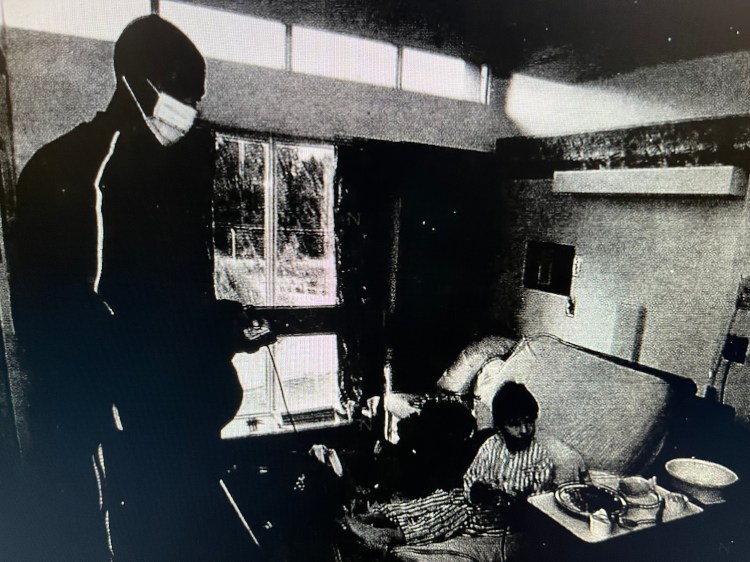

Instead, Shareef works passionately but quietly behind the scenes. A month ago during training camp, he visited Victoria General Hospital [in British Columbia] and waited for all the media to leave before he donned a mask, entered a quarantine unit and held up all the nurses for more than half an hour as he sat talking and playing video games with Konnor, a five-year-old leukemia patient. The picture on these pages was taken by an NBA photographer.

“Those kids are fighting for a chance to be able to live and be happy,” Abdur-Rahim said later. “They haven’t done any wrongs. They don’t deserve it. And believe it or not, it does me some good. It keeps me grounded and makes me realize how blessed I am.”

Back in Atlanta, there was more. In September, the city council presented him with a proclamation for his work with youth. Shareef, William, and other concerned citizens would venture out into Dill Avenue, one of Atlanta’s most-depressed areas, every second Friday night during the summer.

“We’d walk the street where we knew they were selling drugs or where they were doing prostitution,” William says. “At the end, Shareef couldn’t believe it. There would be 15 or 20 of us, and we would get into a circle, hold hands, and sing hymns. Someone would mention Shareef Abdur-Rahim, and the kids would go back home and get their basketball cards. It was exhilarating for Shareef.

“He speaks a lot about what he has been given, that it’s not just for play, for nothing—that along with what he’s been given comes a great responsibility. He’s fully aware that even his reputation is a blessing. And this all at 22.”

Shareef understands how he can affect change, that he has reached a higher plateau where his words carry more weight. That is what sets him apart. “When I leave this situation,” Abdur-Rahim says of playing in the NBA, “I want to be able to look back and say I was able to change things in more than one way, besides just basketball.

“I think at the end of the day, if all people can say about a person is he was a hell of a basketball player, they did a pretty poor job of living.”