[Maybe one day Meta will develop a virtual reality headset that sends its users spiraling back in time and space to the days of Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry West. But until then, if you want to hang with the Big Dipper, Mr. Clutch, Happy, Stumpy, and the rest of their 1970s Lakers contingent, you’ll have to use your imaginations while pouring over printed material from way back in the NBA day.

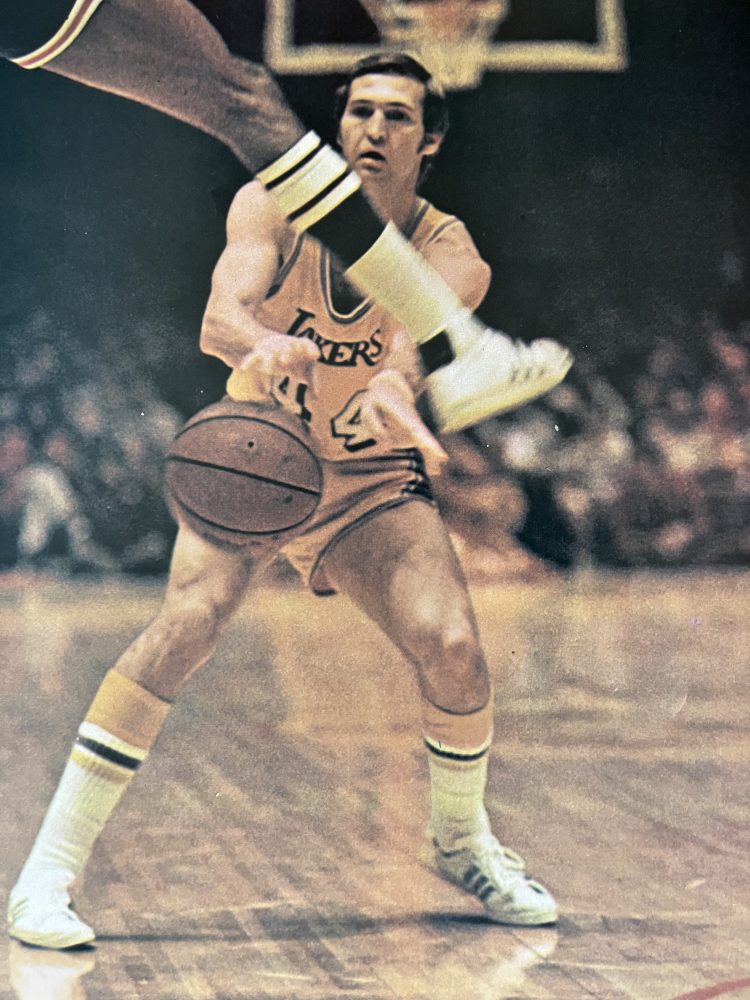

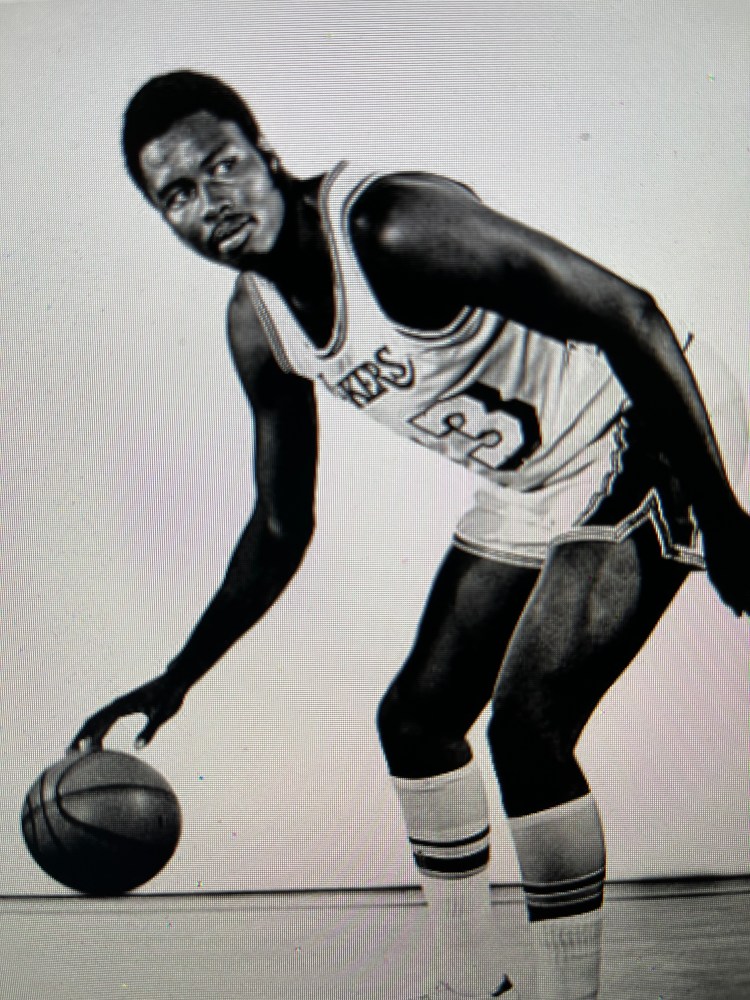

Like this article from Los Angeles Times journalist Jeff Prugh, which he published in the newspaper on October 20, 1972. The highly regarded Prugh chronicles here a few days of traveling on the road with the 1972-73 Lakers. He introduces the story tongue-in-cheek like a Hollywood director rolling the opening credits to a new film: “Executive producer WILT CHAMBERLAIN; produced by WILT CHAMBERLAIN; written by WILT CHAMBERLAIN; also starring BILL SHARMAN, JERRY WEST, HAPPY HAIRSTON, JIM McMILLIAN, PAT RILEY, FLYNN ROBINSON, and introducing TRAVIS GRANT.”

So, lights, camera, and 2,356 words to follow.]

****

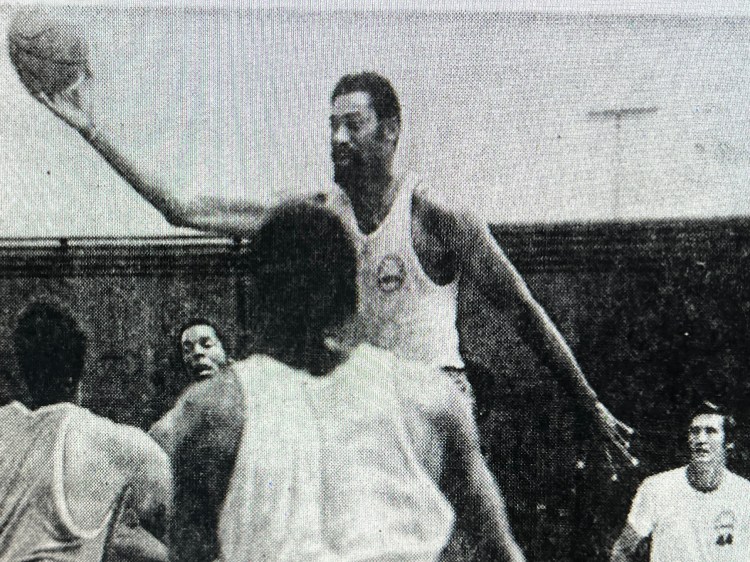

It was opening night of a new 1972-73 season with a new stop on the NBA map in Omaha. One of the last players to arrive in the dressing room of the “world-champion” Lakers was Wilton Norman Chamberlain.

Jerry West’s eyes brightened. “Hey, guys, look who walked in,” he drawled looking up . . . up . . . up . . . at Wilt. “Here comes the new face on our team.”

If Chamberlain suddenly seemed like a stranger to the Lakers, it was because he had hardly touched a basketball since last spring. He had missed all the preseason games—much to the consternation of coach Bill Sharman—because he was demanding more money from owner Jack Kent Cooke.

Presumably, he got what he wanted. You could sense it in his carefree mood as he burst into the locker room, exchanging barbs and laughter with anyone who cared to listen. He also demonstrated he has not lost his touch as master of the put-on.

“Man, I’ve done things on a basketball court that nobody—absolutely nobody—would believe,” he announced to no one in particular. “One time, I hit 63 points in nine minutes in high school—and the other team was holding the ball!”

“Aw, c’mon, Wilt!” somebody yelled. “That’s impossible!”

“Honest to God!” Wilt roared. “Sixty-three points in nine minutes! Look it up. It’s in the papers.”

His teammates snickered, but Wilt tried again. “That night I scored 100 points against the Knicks,” he said. “I would have scored 200 if they hadn’t fouled me so much.”

“Awwwwwww, c’mon,” said his teammates.

“Hell yes, I could have scored 200!” he roared. He gazed across the room at Flynn Robinson, the reserve guard, who was oblivious to the debate. “Isn’t that right, Flynn?” Wilt yelled. Chamberlain always says, “Isn’t that right, Flynn” whenever he needs support for his arguments.

Robinson, caught off guard, looked up helplessly, “Uhhh,” he said, “who was guardin’ you? Anybody?”

John Q. Trapp, the reserve forward, rolled across the floor in laughter. Everybody laughed. Even Bill Sharman, who sat alone in a corner nervously pouring over a scouting report, smiled.

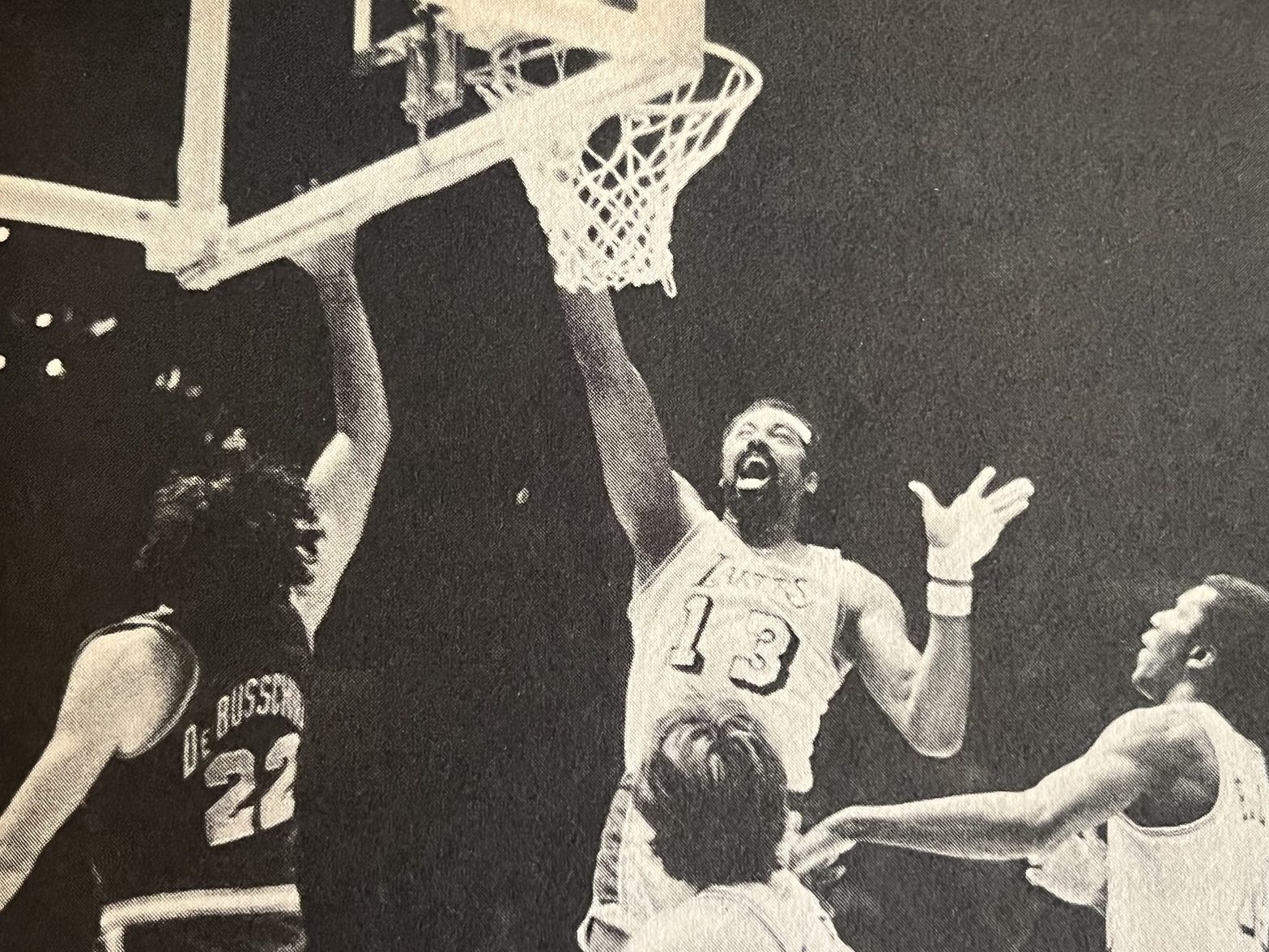

Wilt Chamberlain was on centerstage again as he began his 14th NBA campaign. Unlike Milwaukee’s Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he seems to savor the electricity that swirls around him. Teammates say he is more convivial then he was in the years before Sharman appointed him captain.

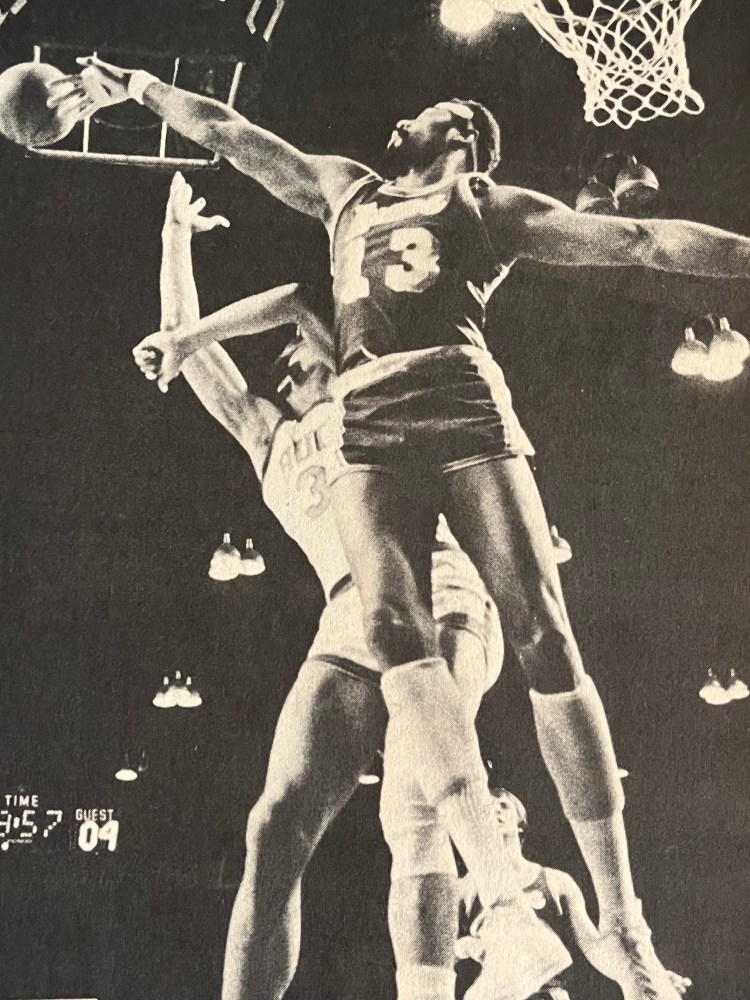

Make no mistake, the Lakers are Wilt’s team. He dominates them, needles them, and has them clinging to his every word. He asserts himself with more than his size (7-1, 275). He is loud, animated, and argumentative. Pick a subject—any subject—and Wilt will pontificate on it, hoping to entice somebody into an argument.

“Really, it’s who he is—not necessarily what he’s saying—that grabs everybody’s attention,” said forward Happy Hairston of the Chamberlain phenomenon. “Any one of us start talking, say, about the space program. Intelligently, too. And nobody will listen. But if Wilt starts rapping about the space program—or anything else—all the guys will stop and listen. It’s always that way. It’s who he is that really matters—and let’s face it, he’s Wilt Chamberlain, superstar.”

****

The NBA is basketball’s most frantic roadshow, a fastbreak from hotels to arenas to airports . . . Omaha . . . Boston . . . New York . . . Cleveland. Cities and games become a blur.

The Lakers are not the same free-spirited, rollicking team that moved west from Minneapolis more than a decade ago with such personalities as Hot Rod Hundley, Rudy LaRusso, and Elgin Baylor. Pro basketball is big business now. The players approach it as a profession, not a joyride. The pay is good—higher than in any other pro sport because the payroll is relatively small—but job security is tenuous.

Nearly every player on the bench of an NBA team is vulnerable because some whizbang sharp- shooter fresh out of college is shooting for his job. Even the starters are vulnerable and live in dread of the night they will lose their assignment to somebody coming off the bench or the injured list.

Pat Riley, part-time starter, knows the feeling. Riding in a bus with the Lakers from a pregame practice session in Boston, he ponders his stand-in role for the team’s leading scorer of last season, Gail Goodrich, who is injured.

“I haven’t slept very well,” he said. “It’s because I’m playing a lot now. I have a lot more on my mind. When I don’t play very much, that’s when I really get a lot of sleep.”

He looks ahead to the night when Goodrich will be flipping his left-handed jumper and twisting layups again. “I’m realistic about it,” he said. “When Gail comes back, it’ll be like last year again. I’ll do all I can to help the team coming off the bench.”

Riley sighs. “But I wouldn’t trade this for anything,” he said. “I knew the other feeling when I played at San Diego. Sure, I played a lot, but we didn’t win. I’m realistic enough to know there are 10 guys on this team who could start for anybody. And Sharman is a great coach to play for. Really, I’m better off right where I am.”

****

They affectionately call him “Big Fella.” Wilt Chamberlain is a proud man in the twilight of his career at 36, going on 40. But sometimes his moods are almost childlike. Take the temper tantrum he threw in Boston, for instance. He was standing in the airport with the Lakers on a rainy afternoon waiting for his luggage. A red-nylon garment bag appeared inscribed with “THE BIG DIPPER” and splattered with water and what appeared to be grease.

A scowl crossed Chamberlain’s bewhiskered face. “Dammit!” he roared. As startled bystanders watched, he angrily gathered up the bag and stalked to a nearby office demanding that the airlines clean it. “Look at this!” he snapped. “Crap all over my bag! What did they do on this flight, man? DRAG it all the way!”

The man behind the counter wrote Chamberlain’s name on the form and asked, “How long have you owned the bag?”

“Oh, seven or eight months,” said Wilt.

“How much did you pay for it?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I think it was $2,000. I bought it in Bangkok.”

A few minutes later, Lynn Shackelford, the Lakers’ color commentator on the radio, stood in the terminal and made certain that all luggage was transmitted to the team bus. He observed the bag that read “THE BIG DIPPER” and grinned. “Boy, Wilt really loves that thing,” he said. “I’m surprised he didn’t carry it aboard the plane this time, instead of checking it in. That’s what he always did last year.”

****

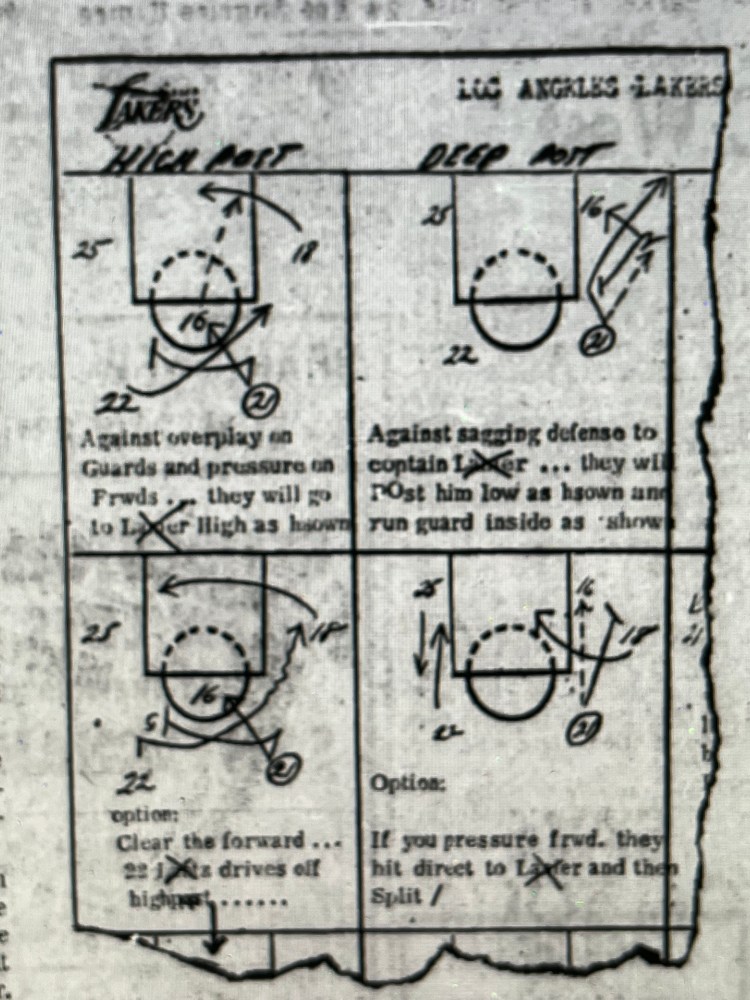

It is the day before Friday the 13th and a showdown with the Boston Celtics. Sharman calls his customary pregame strategy session. He has a three-page scouting report and films of the Celtics—both prepared by Bill Bertka, the newly hired Laker scout.

But the Lakers don’t seem to take the meeting seriously. They laugh and exchange wisecracks as Bertka stands solemnly before a chalkboard sketched with Boston plays, explaining the report page by page. “Their offense is initiated very quickly—they don’t horse around,” says Bertka.

“You’re going to see in this film that they get most of their baskets off fast-breaking situations. Havlicek and White are always looking for blind picks, so when they set up, our guards are going to have be looking for that.”

From the back of the room comes Chamberlain’s voice. “You’ve gotta take a speed-reading course to get through this,” he mutters, shaking his head.

Jerry West grins. “Look at this,” he said. “It says we should molest the rebounder. I don’t think that’s very legal.”

There is laughter, but Bertka moves on. He turns on the projector, and the Celtics and the New York Knicks are on the screen. “Watch how quickly they convert from defense to offense,” he says. “Remember, Havlicek, Chaney, and White really move on the fastbreak. We’ve got to get back and not let them set up.”

The films cost about $500 per game and are edited to eight minutes to key plays by Bertka, whom the players have nicknamed “Cecil B. DeMille.” It is believed that the Lakers are the only NBA team which scouts opponents extensively on film.

The film ends, and the Lakers applaud. Somebody says, “Let’s hear it for Cecil.” Everybody laughs, and Bill Bertka smiles hoping his handiwork will help offset the complacency that seems to have settled over the NBA champions. But his hopes go for naught. The next night, the Boston Celtics turn those Laker smiles into long, long faces, 112-104.

****

“Since it’s so late,” said Bill Sharman, addressing the Lakers, “We won’t have any shoot-around tomorrow morning.” Sharman usually schedules day-of-the-game shooting practice to loosen up muscles. The news was greeted with applause by the team that had just been whipped by the Celtics and now was leaving by bus from the Newark airport for its mid-Manhattan hotel.

Then Sharman asked: “What time tomorrow do you want to look at the film of the Knicks? 11:30? 1 o’clock?”

What’s this? A coach ASKING his players instead of commanding them? That’s right. With Sharman, the player-coach relationship is man-to-man, not father-to-son. He is undeniably the boss, but he also firmly believes in spreading a little democracy around.

Sharman’s question is greeted by silence at first. Then Wilt speaks up from his customary front-row seat” “What time’s the football game over?”

Another Laker says, “Let’s watch the film right after The Lone Ranger.”

A few players chuckle, and Sharman says, “12 o’clock.”

More silence.

“OK, 12 o’clock it is,” he says.

Suddenly Wilt bellows: “Let’s make it 12:30!”

“Let’s have a vote,” counters somebody.

“It’s gonna be 12:30, because I can’t sleep at night,” says Chamberlain, a well-known insomniac.

“All right, Wilt,” says forward Jim McMillian, acidly, “you just come down to the film when you want to.”

A couple of players laugh, and Chamberlain retorts, “Yeah, you tell ‘em, third-year man.”

In a moment, the laughter dies as the bus rumbles through the post-midnight traffic of the Holland Tunnel and into Manhattan. Jerry West has made this journey umpteen dozen times. He is engrossed in a pamphlet titledPentagon Papers Digest, and he shares its contents with a reporter. “Read this paragraph,” he says sadly, pointing to the middle of the page. “And read this one, too,” he adds, shaking his head.

For the moment, West’s thoughts were 12,000 miles away from the roar of the crowd. He had shot miserably against the Celtics. He was trying to forget the Lakers’ first defeat of the season, not to mention the words of a Boston spectator who had yelled, “You’re through, West! You’re done!”

Now he was talking about Vietnam, about Nixon and McGovern, about taxes and drug abuse. He talked about the challenges—and the joys—of rearing three young sons in Brentwood. At 34, life for Jerry West is more than double picks and high posts and “three-to-make-two” free throws. He looks beyond the next games. He talks about what it will be like to walk away from the game that pays him $300,000 a year.

“Some people tell me how difficult it will be for me to retire,” says West, who is noncommittal about a retirement date. “They say I’ll miss all the adulation. No, I won’t. Not really, I’ve had a lot of adulation, and the game has given me so many other things, besides.”

He thought for a moment. “I’ll know when it’s time to quit,” he said. “I know one thing. I’ll do it long before I ever start scoring only two and four points a game.”

****

Travis Grant, the quiet rookie, was a million miles from Kentucky State College. He was sitting in the first-class cabin of the Cleveland-to-L.A. jetliner, and the frequent smile on his face told you he didn’t seem to mind losing money to the guy who is beating him badly in a card game called “Tonk.”

And Chamberlain didn’t mind telling everybody within earshot that he was beating Grant “by 40 games!”

“The only way you can beat me, Travis, is by cheating—and you wouldn’t dare do that,” said Wilt.

Wilt repeatedly boasted about how he was winning all the money, and how there was “no way” Grant could beat him.

“But what about yesterday?” asked Grant.

“That was yesterday,” Wilt yelled. “This is today.”

For four hours, Wilt was the focal point of the first-class section. Strangers stared at him. Teammates needled him. And a passenger across the aisle, cartoonist Johnny Hart of the comic strip series B.C., sketched a caricature of Wilt dwarfed by a fellow on stilts who was saying, “You mean they call you Wilt the . . .”

Said a stewardess who handed the finished cartoon to Wilt: “He didn’t like it that much. In fact, he was sort of rude.”

Chamberlain casually fielded questions from a reporter. “Will he keep playing until age 40?”

“Nope. The season is too long now. It’s getting longer and longer every year. The practices start earlier, and the season ends later. There’s too much pressure. It lasts too damned long.”

“How difficult will it be to quit?”

Wilt grinned and ducked the question. “Aw, it won’t be tough at all,” he said. “Hell, I can make more money just beating Travis every day.”

An hour or so later, the plane landed at Los Angeles International Airport, and Wilt let it be known—once and for all—that he had beaten Travis Grant at Tonk. “And if I EVER lose to him,” he announced, “I’ll jump right out of the airplane. Without a parachute, too!”

Again, all ears were tuned in to Wilt. “And when I land, I’ll walk away uninjured!” he went on. “I’ll make a perfect landing right on the foul line somewhere. And I’ll shoot two free throws right away.”

He paused and deadpanned: “And I’ll make ‘em, too!”