[The long-time basketball writer Charley Rosen passed away last September at age 84. Rosen had his critics, deservedly so, but he was prolific and tapped out some good books and fantastic magazine articles over his many years at the keyboard. Here’s one of those fantastic magazine articles published in the August 1974 issue of SPORT. Rosen’s subject: Willie Wise of the ABA’s Utah Stars. Enjoy!]

****

If a word was out on Willie Wise, that word was “weird.” He’d had a contract dispute with the Utah Stars before the 1973-74 American Basketball Association season, and he had insisted he wasn’t going to sign. Not because they weren’t offering him enough money. Because he was a Jehovah’s Witness, and he knew that the proposed contract was meaningless. Why? He knew that before the new contract expired, the world was going to come to an end.

Naturally, I was a little wary when I knocked on the door of the apartment in Salt Lake City. I was prepared for almost anything. Anything except a playful, friendly man, who had passed quickly through his end-of-the-world phase and was now looking beyond his basketball days to a career in trucking.

Willie Wise opened the door, yanked on my beard and gave me a big smile. “What are you?” he said. “Six-foot-eight? We’ve got a shooting practice later. Why don’t you come and suit up with us.”

I mumbled something about not being in shape, except for my typing fingers.

Wise shrugged. “That’s cool,” he said. “Then let me show you around town.”

And as he showed off the delights of Salt Lake City, Willie Wise never took his right hand off the walnut-knobbed shift stick of his 1973 BMW Bavaria. The first stop was Temple Square, a busy intersection bounded by the famous Mormon Tabernacle, a municipal office building, the Zion’s National Bank, and a department store. In the middle of the square stands a statue of Brigham Young, the city’s founding father and spiritual beacon. The huge bronze statue is positioned so that BY’s back is turned toward the temple and his open hand stretched toward the bank.

“I can really dig living in Salt Lake City,” Wise said as he turned left on Broadway. “The streets are wide, the red lights are synchronized, and there’s never any heavy traffic.

****

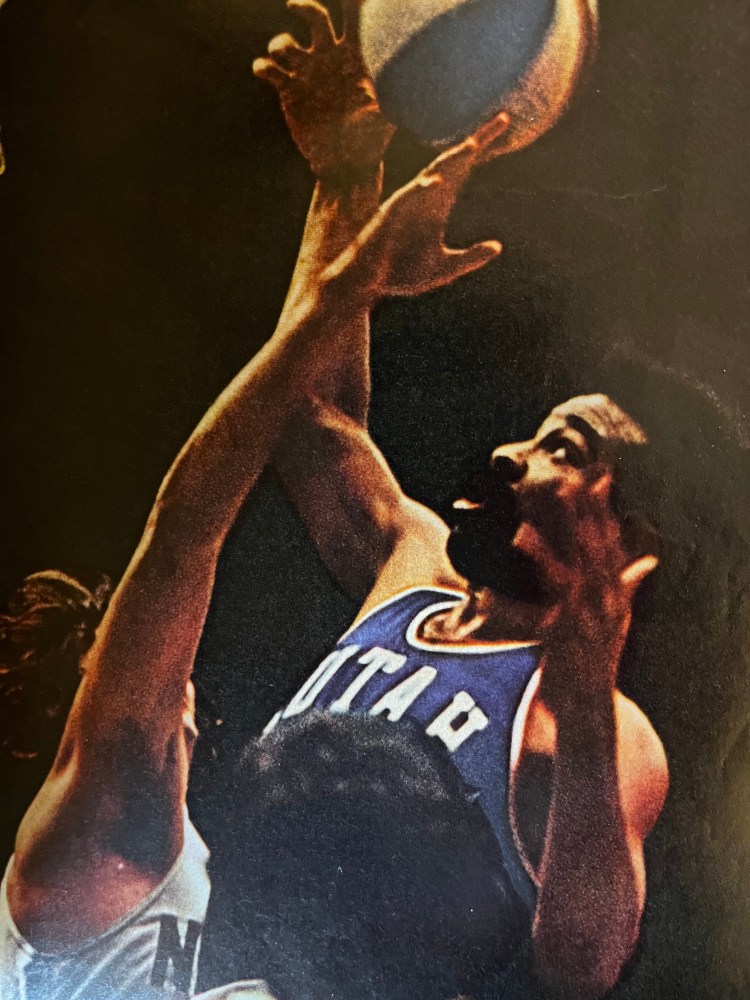

Willie Wise is one of Salt Lake City’s best-kept secrets: A three-time ABA all-star, bull-shouldered, 6-foot-6 forward with a pro career average of over 20 points per game, a man whom Dave DeBusschere calls one of the finest two-way ballplayers in basketball. But the influential media beehives back East never get the Stars’ home box scores in time for the morning editions or their evening news programs. So nobody does any national buzzing about Willie’s sweet jump shot and smooth-as-honey moves. Not that Willie minds being practically anonymous. He would just as soon drive a truck as drive to the basket.

“When we take a bus to the airport,” Wise says, “I make it a point to always sit right behind the driver. So I can share his perspective and just check out how he handles different situations. When my basketball career is over, I’d like to own a fleet of trucks.”

Motor vehicles and basketball have always fascinated Willie. The first car he ever owned was a dented 1956 Chevrolet, which he used primarily to putter around the campus at Drake University. During his senior year there, Willie averaged 15 points a game and seven miles a gallon. When the San Francisco Warriors made him a fifth-round NBA draft choice in 1969, Wise quickly ditched the Chevy and scoured the car magazines looking for just the right machine to buy with his anticipated bonus money. But Bob Feerick, the Warrior general manager, figured that the dimes he had spent calling Willie were bonus enough.

“He must have thought,” Wise says, “that since I was a native of San Fran, I’d be horny to play for the Warriors. Which I was. Anyway, Feerick told me that I could come to tryout camp if I wanted to—without a contract and without any expense money.”

Willie also learned that the Warriors roster was already clogged with nine no-cut contracts and that Feerick was saving one more spot for the number-one draft choice, Bob Portman. But a recommendation from Willie’s college coach, Maurice Johns, to the ABA’s Los Angeles Stars (they made the pilgrimage to Utah in 1970) resulted in an all-expenses-paid trip to the Stars’ rookie camp in the summer of 1969. Wise was easily the camp’s standout, and he was rewarded with a contract for $17,000. A number which beat nothing, but still caused him to regret the unconditional release of his old Chevy.

Bill Sharman was the Stars’ coach then and, among other things, he worked a great deal on tuning up Willie’s shooting—a move which helped Wise’s average go from 15.2 points his rookie year to 22.3 last season. Willie’s salary has also grown into six very nice figures.

“A Chevy?” he now asks. “Are you kidding?”

****

The next stop on the Salt Lake City grand tour was the Tri-Arch Travel Lodge, where the elite meet to eat in Salt Lake City, and I could see why. A pert 15-year-old named Liz broke away from the pack and came slinking over to Willie. “Hey Will,” she said, arching her eyebrows. “What are you doing after the game tonight?”

Wise turned his sleepy, round face into a bad imitation of a scowl. “If I ever catch you in here messing with ballplayers again,” he said, “I’ll whip your ass and call your mama to come fetch you.”

After Liz had pouted her way over to another ballplayer, Willie gave me one of his wide-eyed looks. “Very hospitable people here in Salt Lake,” he deadpanned.

****

When Wise was a 10-year-old street urchin in San Francisco, he and his buddies used to test their mettle by accepting each other’s dares. One day, the task was jumping off a two-story building. Willie passed summa cum laude, but his legs haven’t been the same since. Seventeen years, one bone spur, and one major knee operation later, Willie is forced to wear lead weights around both ankles. Even when he parties. And it does cause some difficulties.

“It creates the need,” he says, “for a whole different touch on the break and on the gas pedal.”

But Walt Simon, the Kentucky Colonels’ fine forward, feels little sympathy for Willie. “I’d hate to see what he could do on two good wheels. Man, he’d be the atomic bomb.

“Willie is tough enough as it is,” Simon continues. “He doesn’t block many shots, but he never lets you have a good one either. He is surprisingly strong, and he uses his hands very well on defense.

“But his offense is the strongest part of his game. Willie is one of the most dangerous clutch shooters in the entire league. Willie also plays very smart—he gets everybody into the game, he goes without the ball, and he has the super-good fakes. When he’s going strong, he can get any defensive player off his feet. Then he’s gone.”

K.C. Jones, the coach of the NBA’s Washington Bullets, once a brilliant defensive guard on the Boston Celtics, served some time in the ABA as coach of the San Diego Q’s. “Willie Wise is one of the best forwards in basketball,” says K.C. “He’d be an all-star in any league.”

The next guidebook attraction turned out to be Salt Lake City’s one-block-long Black neighborhood. The Mormon Church dominates Salt Lake City, and the Mormons believe that the entire Black race was descended from Cain. That explains why no Blacks can be ordained in the Mormon Church and helps explain why Zelmo Beaty, Utah’s veteran center, is the team’s only Black player who lives in Salt Lake City all-year around. [Ed. Note: Rosen refers correctly to a traditional—and racist—Mormon belief that would be dropped in 1978 into the scrapheap of LDS doctrine and history.]

As we drove quickly through the mini-Black neighborhood, Willie was grim. “I never spend any time here,” he said quietly.

Our next stop was the Salt Palace, a handsome, well-appointed arena, too appealing for a semi- retired jock to resist. The only thing that bothered me was the Stars’ version of “Horse,” a shot-matching contest. The only shots that counted in their game—and the only shots that must be duplicated by the shooter next in line—are the ones that go in the basket without touching the rim. Under this kind of pressure, my game rapidly deteriorated. Before I folded completely, I decided to play my trump card on Willie, whose turn was right after mine.

“Lookie here,” I said, as I hoisted up a 25-foot two-hand set shot that rimmed the basket and spun out.

“Outasight,” Willie responded as he dribbled the ball behind his back and between his legs before flipping up a 35-foot two-hand set shot—that hit nothing but net.

****

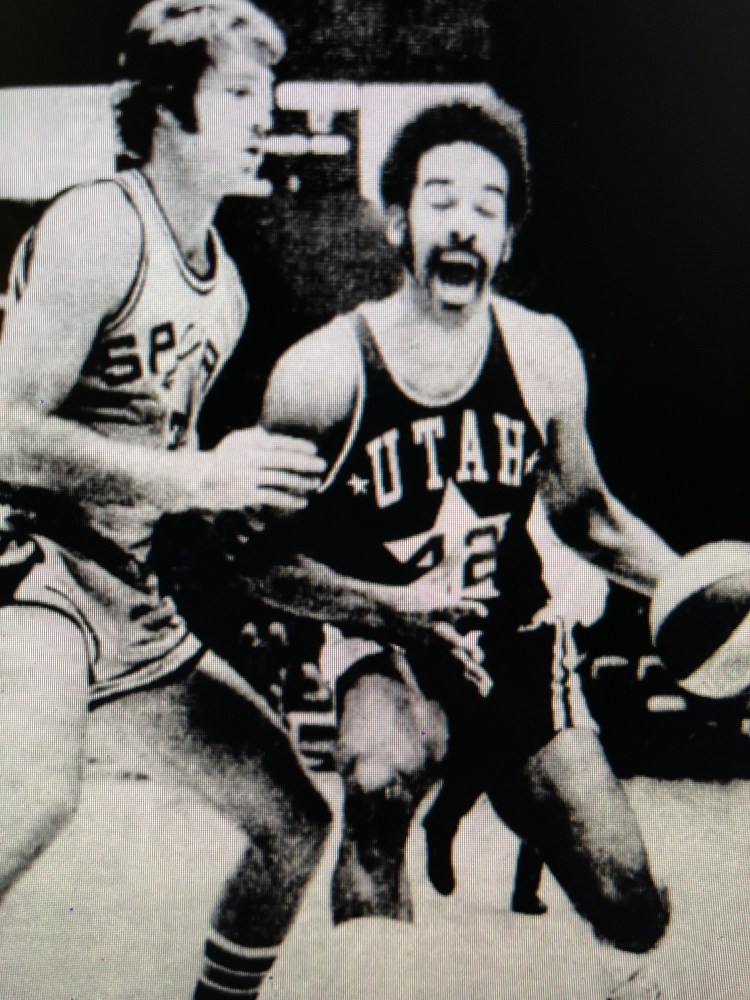

The game that evening was the seventh in the ABA’s semifinal playoff series. After jumping off to a 3-0 lead, the Stars had lost three games in a row to the Indiana Pacers. Indiana’s strongman, George McGinnis, had gone wild under the boards in the Pacer victories, and Utah coach Joe Mullaney had decided to switch his team’s defensive assignments. Willie was scheduled to try and control big George, and Willie was worried that the extra burden might cause his bad knee to self-destruct.

But there was to be more pressure on Willie: Before the game, he was informed that he had been the top vote-getter for the league’s All-Defense team. “It’s a nice honor,” he said, “but I didn’t play a pound of defense all year.”

As the two teams started jostling for position for the opening tip-off, there were two glaring mismatches on the court: George McGinnis is two inches taller than Willie and 20 pounds heavier.

It was also obvious that Willie’s uniform did not quite match his teammates. All the others Stars wore two patches on the sides of their trunks—a tiny American flag and a replica of the seal of the State of Utah. Willie’s trunks were blank. The Stars’ management is raked by public flack every year, but Willie just ignores all the noise and goes about his business.

Against the Pacers, Willie worked to keep the ball away from McGinnis. Wherever George turned, he found Willie’s body blocking the way. As the game wore on, McGinnis became more nervous, frustrated, and confused. He finished with a poor-shooting 14-point game; the Stars won by more than 20.

****

A win moved the Stars into the championship series against the New York Nets. In New York, I gassed up my 1969 Volvo and returned Willie’s hospitality. I took him and his date to Nathan’s Famous for lunch, to Jack Dempsey’s for cheesecake, and to Lincoln Center for some ballet. (“It was nice,” Willie reported. “It’s the same movements as basketball, but nobody plays any defense.”) And since injuries to Zelmo Beaty and Gerald Govan had reduced the Stars’ squad to only nine healthy players, I let Willie talk me into going to St. John’s University for a practice session.

My picks were received with acclaim by the shooters I teamed up with, and I even managed to make a couple of shots. But I still felt as though I was the only one out there who did not quite comprehend what was going on. I did, however, understand how much fun it was to play basketball with Willie Wise.

First, it requires a full 15 minutes of loosening-up exercises before Willie’s knee is flexible enough for him to run, and it would be foolish for him to go too hard in a practice, especially during the playoffs. But when the two of us were working on something, I could detect the gravity of Willie’s facial expression decomposing into a huge grin. And I could see him let out a few notches to try and make the situations work. When I set him up for a relatively free 15-foot jumper, and when his shot touched only air as it went through the hoop, my mask cracked long enough for me to smile along with Willie.

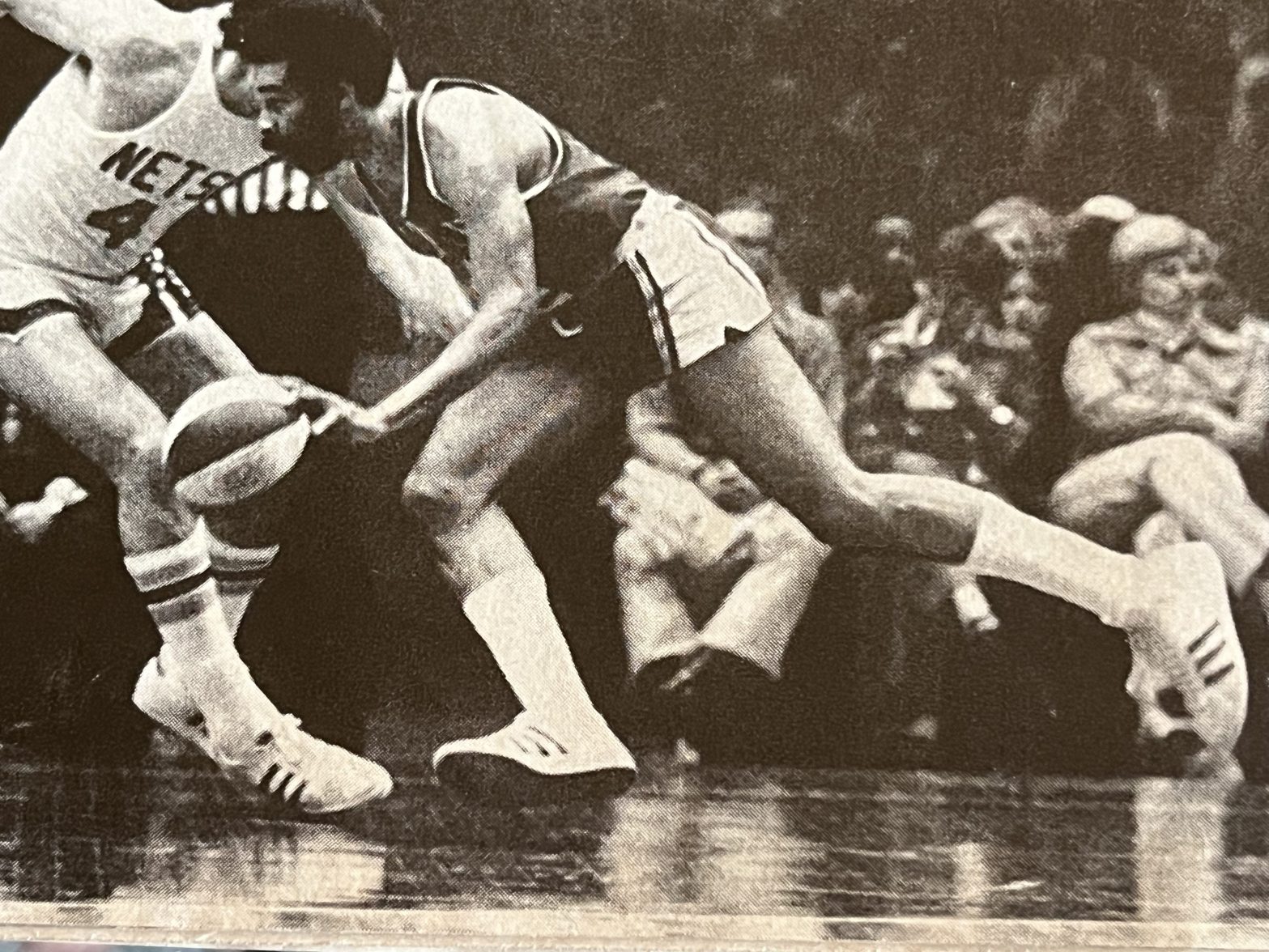

The series with the Nets wasn’t quite so funny for the Stars. Zelmo Beaty had missed the first two games with a groin infection, and the Stars tried to get away with Willie guarding 6-foot-9 Larry Kenon and controlling the offense. But Julius Erving, Dr. J, made everybody else look like veterinary interns. In the first game of the series, Dr. J had 41 points in three quarters before Willie switched over to him. The Doctor finished with 47. Wise did a strong defensive job on Erving later in the series, but the end result was a 4-1 Nets victory.

Another result was a very tired Willie Wise. In the locker room after one of the games, a radio man came over and stuck a microphone in his face. “Hey, man,” Willie said, real friendly, “why not interview those other cats?” And he pointed to his teammates. Willie obviously isn’t hungry for personal publicity, yet he seemed genuinely interested in this article for SPORT. I asked him why.

“Well,” he said and smiled, “I just want the boys back in San Fran to check it all out.”