[Firsts are often hard to pin down. But NBA pioneer Bob Davies was clearly one of the first to popularize the behind-the-back dribble in the 1940s, prompting most coaches of that era to roll their eyes. “I do not advise dribbling behind your back,” wrote Red Auerbach in the 1952 edition of his classic Basketball for the Player, the Fan, and the Coach. “If you happen to be an expert such as Bob Cousy or Bob Davies, you still should realize that it is not nearly worth the risk involved for what it accomplishes.”

Auerbach didn’t enumerate the risks, neither did he ever convince Davies, then the star of the NBA Rochester Royals, to quit the fancy stuff. In this article, from the February 1948 issue of Sport Magazine, Davies gets the Royal treatment about his risky dribbling (toned way down to avoid making enemies) and more from journalist Bill Roeder of the New York World-Telegram. The article, typical of 1940s sports journalism, is a little fawning in places. But it offers a nice look into the National Basketball League (NBL), which would merge with the Basketball Association of America in 1949 to form the NBA. If you’d like to read more about Davies, be sure to check out Barry Martin’s 2016 book Bob Davies: A Basketball Legend.]

You, too, can learn to dribble behind your back. Bob Davies says anyone can do it, and while the stunt is not recommended as a sure approach to social favor, it does come in handy on the basketball floor.

Dribbling is one of the things Davies does for a living. The Rochester Royals, a crack National Basketball League team, have his name on a contract that is said to specify $12,000 [about $134,000 today] for the five-month season. That’s going pretty steep for basketball talent, but, in Davies, the Royals have a performer with spectacular ability and corresponding crowd appeal. He is something almost extinct in the modern game: a showman without a whistle.

Have you ever seen the House of David baseball team put on one of its pepper shows? Davies can duplicate this sleight-of-hand routine on the court despite the greater bulk of the basketball and the fact that his hands are uncommonly small. He can launch the ball in one direction, and make it go the opposite way. He can actually dribble in reverse, shifting gears in full flight to change hands behind his back without losing speed or control. Once, in an exhibition game at Albion, New York, he drop-kicked a field goal.

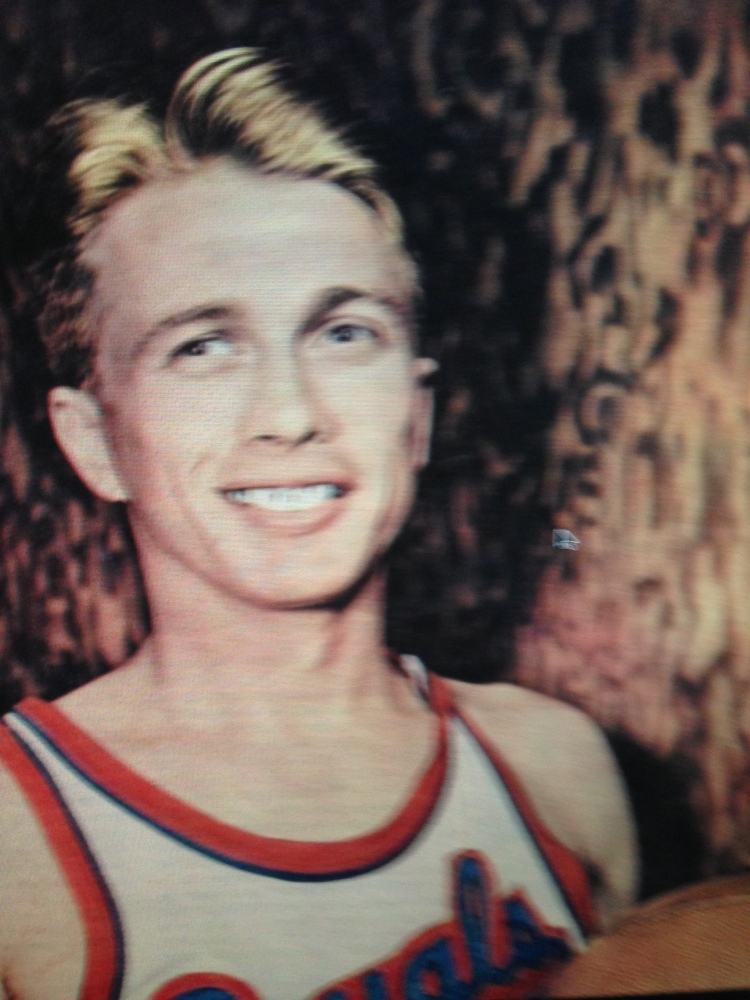

Nevertheless, the Royals do not exploit Davies as a clown. This is necessary because he is able to draw fans on his merits as a player and because of his naturally colorful style. His appearance—he is a lean, smiling blond, an All-American boy type—insurers a considerable bobby-sox following. His court mannerisms, flashy deftness, and graceful mobility somehow set him apart from the run of players.

In addition, Davies plays winning basketball. On a team that includes a number of stars and is rated with the best in the country, he is the acknowledged standout. Last year, he was voted the league’s most valuable player. He was also the most industrious. Between games with the Royals, Davies found time to coach at his alma mater, Seton Hall College, in South Orange, New Jersey. This kept him on trains, planes, and basketball courts almost continuously. But in April, when the Royals were involved in the playoffs at Chicago, he was still going strong.

Seton Hall by this time was playing baseball. After an early afternoon drill on the diamond, Davies flew to Chicago. He played that night and caught a plane back to Newark for a baseball game the next day. But when the game was rained out, he rushed to the airport and surprised the Royals, not to mention the opposition, by appearing in uniform at game-time. All in a day’s work . . .

But Davies is no longer a catch-as-catch-can coach. He has taken a leave of absence from Seton Hall, and will live in Rochester the year ‘round to work for the Royals, and for a local auto agency. He is now 27 years old, married, and has a three-year-old son. He feels he will be able to play topflight basketball for another five years. Meantime, with a possible return to coaching in mind, he is working toward a master’s degree in physical education, and will complete his studies at Columbia this summer.

Here is the way Davies is likely to spend a day in Rochester during the season:

In the morning, he reports to work at Whiting-Buick. He is learning the business by stages, moving from personnel to service to the used-car division, and so on. He goes to work at eight a.m., finishes by six p.m. But the management makes allowances for Davies’ outside commitments—the games, of course, and various luncheons and clinics which the pro players are asked to attend.

Maybe there will be an ad men’s luncheon downtown. If this is the case, Davies checks in at the law office of Sconfietti and Harrison. The Harrison brothers operate the Royals. Les, who organized the club, is president, and Jack is secretary. Their four-room office serves as headquarters for the players.

After work, Davies goes home to his apartment in the neighborly Vick Park section. There he will have dinner with his wife (she is Mary Helfrich, a hometown girl from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), and little Jimmy. Although Davies is a Lutheran, his son was named after Father James Carey, the athletic director at Seton Hall.

If there is a game that night, Davies drives to the Edgerton Sports Arena. The Royals play their home games in this auditorium, which seats about 4,000 in twin stands banking up from the playing court, a regulation floor with wooden backboards. Most games are sell-outs, and the Harrisons feel that Rochester, with its population now 330,000, could support a bigger arena.

The Royals are a fraternal team, and after a game, Bob will join the other players in a beer or two. Hard liquor is out. Although there is no rule against it, Davies doesn’t smoke. Next stop is often the railroad station, because the schedule sometimes sends the Royals out to Fort Wayne or Toledo, or maybe Oshkosh, for a game the following night.

On the trains, the basketball players, like most traveling athletes, pass the time with card games. Davies favors bridge, and the Royals came up with several rookie bridge addicts this year—John Mandic, Bill Calhoun, Joe Lord, LeRoy King, and Andy Duncan. When the players have time on their hands out of town, they generally go to the movies.

Late in the Fall, the Royals added another ex-Seton Hall ace, Bob Wanzer, to the roster. Another cage star from the South Orange school who will probably turn pro with Rochester after graduation is Frank (Pep) Saul, whose playing style is similar to Davies.

Although Davies has been out of the college more than five years, he still looks like a sophomore. He has blond hair, lots of it, and a young face. He weighs 185 pounds, and is 6-feet-1.

“People don’t believe me when I tell them my correct height,” he says. “I know that on the court I look 5-feet-9 or 10. That’s because there are so many real big boys, and because I have a habit of running sort of hunched over, with my head tucked down.”

Davies feels he is about an average-sized player in his league. He is slender, and doesn’t look particularly strong, but he is seldom out with injuries. Perhaps one reason is that he wears knee guards, a protection many of his contemporaries have abandoned. On his shirt he wears No. 11, a longtime favorite. “Just habit,” he explains. “It was good to me in college.”

At Seton Hall, Davies played under Honey Russell, an old player who has since returned to the pros as a coach. They Royals have two coaches. One is Edmund Malanowicz, who has another job as principal at Sloan High school, near Buffalo. When Malanowicz is unable to make trips, Les Harrison, the owner and former player, runs the club. For years, Harrison operated independent pro clubs in Rochester. When he got a National League franchise in the Fall of 1945, Harrison immediately went after Davies, who was then in the Navy, but due for a discharge.

“There was one boy I didn’t want to let get away from me,” Harrison recalls. “I had seen him with Seton Hall and Great Lakes, and I knew he was the greatest offensive player in the business. I had to out-bid every pro club in the country for Davies, but I got him. He joined us late in December, after our season had started.

“Bobby wasn’t in top shape, naturally, and his style is so different that about three-quarters of the season went by before the rest of the team learned how to play with him. So there were times when he didn’t look too good. In many a game, we had to pull the guy.

“But finally he and the others meshed, and ever since then Bobby had led our fastbreak attack. He is a great shooter, passer, and hustler. Bob is always in motion. He brings the ball downcourt faster than any man in basketball, and he is able to jump in the air and still control the ball for a shot or pass.”

When Harrison set out to organize his Royals, he had Davies and three other players in mind as a nucleus. The others were Andy (Fuzzy) Levane and Bill (Red) Holzman, New York City products from St. John’s and CCNY; and Al Cervi, who comes from Buffalo and never went to college, but is one of the most respected of the pros. Last year, Cervi led the league in scoring.

For the most part, the Royals play an orthodox game featuring fast passing and clever shooting. Davies, who used to guarantee at least one basket a game from his trick repertoire while at Seton Hall, now uses the stunts only for functional purposes of deception, never for show.

“We will not make a sucker out of any league club with that fancy stuff,” Harrison maintains, “because we never know when it will strike back.”

Davies agrees. Besides, he says, the opposing pros are too smart. They are so hard to outwit, for instance, that Davies has forsaken his famous behind-the-back dribble. He tried it in league games three or four times, and got nowhere. So now the stunt is saved for the 20-odd exhibition games the Royals play in various small towns.

“It’s an easy trick to do,” Davies says. “Anybody who plays basketball can master the mechanics of it. You simply shift control of the ball from one palm to the other, behind your back. But knowing just when to use it is another thing. You’ve got to have snap judgment, or you’ll mess up the play and look silly. It’s also a trick you’ve got to practice every day, which is another reason I don’t use it in our league. We don’t have time to practice because we’re playing or traveling almost every night.”

It may be an easy trick, but Davies admits he doesn’t know of anybody else who has used the behind-the-back dribble successfully. The first time he tried the play himself, it almost backfired. This was at Seton hall in a game with Scranton university. Davies had practiced his revolutionary dribble for three years, and was risking it in competition against a pretty good defensive man. Well, it worked, alright, but when the Scranton guard went lunging past him on the wrong side, Davies himself was so surprised he missed an easy layup shot.

Back home in Harrisburg, Davies was better known for his accomplishments in marbles (state champion) and in baseball (best kid infielder in town) than in basketball. His development on the court was slow and frequently discouraging. He was small, only 4-feet-11 as a 12-year-old. The junior high school coach benched him in favor of a six-footer, and for a time he played only in alley games , with a rubber ball and a trash can for props.

But, although he was the 13th man on the JV squad as a sophomore in high school, Davies began to grow and improve by leaps and bounds—but literally. That was the kind of play he developed, a leaping, jumping, quick-passing, breakneck style that soon won him at place on the varsity. It was a new kind of basketball at the time, and Davies says he acquired it from one of the other players at John Harris High, a tall black kid named Dick Felton.

Even in his high school days, Davies took great pains to refine his method of play. From Bobby McDermott, then a touring pro who played Harrisburg occasionally, he picked up the fadeaway set shot. McDermott would bluff a bounce pass to his guard withdraw. Then he would fall back and release the set shot. The idea was to give the shooter additional room and more time to get set.

Later, Davies learned to drag his right foot backward on foul shots. This was to create proper balance . He now converts about 80 percent of his foul tries. As a cutter and drive-in shooter, Davies is fouled frequently.

“I usually step up there seven or eight times a game,” he says. “That means so much gravy and points, and it’s also a sort of measure for me. I can tell whether I’m driving or not by the number of fouls I draw. If I don’t step up to that line but once or twice a game, I figure I’m loafing. It’s a pretty reliable gauge.”

Although Davies has small hands and short fingers, he was a fine baseball player, good enough to be picked up by the Boston Red Sox as a second-base prospect. When he insisted on going to college, the Red Sox suggested Seton Hall because the coach there, Al Mammaux, was an excellent hand with young players. In time, Davies became a smooth college infielder. But when he came out of the service, he decided basketball and coaching offered better opportunities.

In a season that is one to two months shorter, Davies makes more money than 75 percent of major league ballplayers. And nobody cares whether or not he can go to his right . When you can dribble behind your back, it doesn’t make much difference.