[This article, from Popular Sports’ 1975 All-Pro Basketball edition, tells the story of Dave Bing’s mid-career vision problems. Bill Halls, who covered Bing and the Pistons for the Detroit News, offers a nice account of Bing’s blurry comeback and commitment to the franchise. As Bing states in the article, “I want to be the first basketball player to begin and end his career in Detroit.”

Oh, but it was not to be. As Halls’ article went to press, Bing’s future in the Motor City took a left turn. It wasn’t Bing’s blurry vision that threw him off course. It was that root of all evil: money.

Before the 1974-75 season, long-time Pistons owner Fred Zollner sold the team to a local ownership group, headed by industrialist Bill Davidson. As part of the deal, Zollner requested that the team’s coach Ray Scott receive a generous raise for his job well done in turning around the franchise. Davidson and crew followed up with Scott—and the news of his good fortune raised eyebrows in the until-then united locker room.

The most arched of those eyebrows belonged to reserve Don Adams. He wanted a raise, too, for his contributions to Detroit’s turnaround. Adams, idealistic and persuasive, convinced Bing that, as the face of the franchise for several seasons, he, too, deserved a bump in pay for his job well done. When management said no, Bing and Adams briefly held out in protest to start the 1974-75 season. This once-tight team was now pointing fingers. In January, Scott finally pointed the finger at Adams. “You don’t need to be on my team if you’re going to disrespect me,” Scott remembers saying and then cutting Adams. Bing predictably sided with Adams, and then unpredictably excoriated Scott in the press.

The two patched up their differences, but the Pistons finished the season with a hugely disappointing 40-42 record and an early exit from the playoffs. The disappointment had Scott and the new owners anxious to shake things up, and that meant Bing—Mr. Piston—was expendable. By the summer of 1975, Scott dealt Bing and a first-round draft choice to the Washington Bullets for the younger point guard Kevin Porter. “I wanted a quick-strike team,” Scott explained the trade for the quick-strike Porter. “That’s the way the NBA was going. Everybody wanted to run like the Celtics.” Ironically, after two seasons in his native Washington, Bing ended his career with, you guessed it, the Celtics.]

October 16, 1971, was a pleasant, sunny fall day in Ann Arbor, Mich. The National Basketball Association season was barely a week old and University of Michigan football fans were looking forward to that Saturday’s Big 10 game with Illinois and, eventually, another trip to the Rose Bowl.

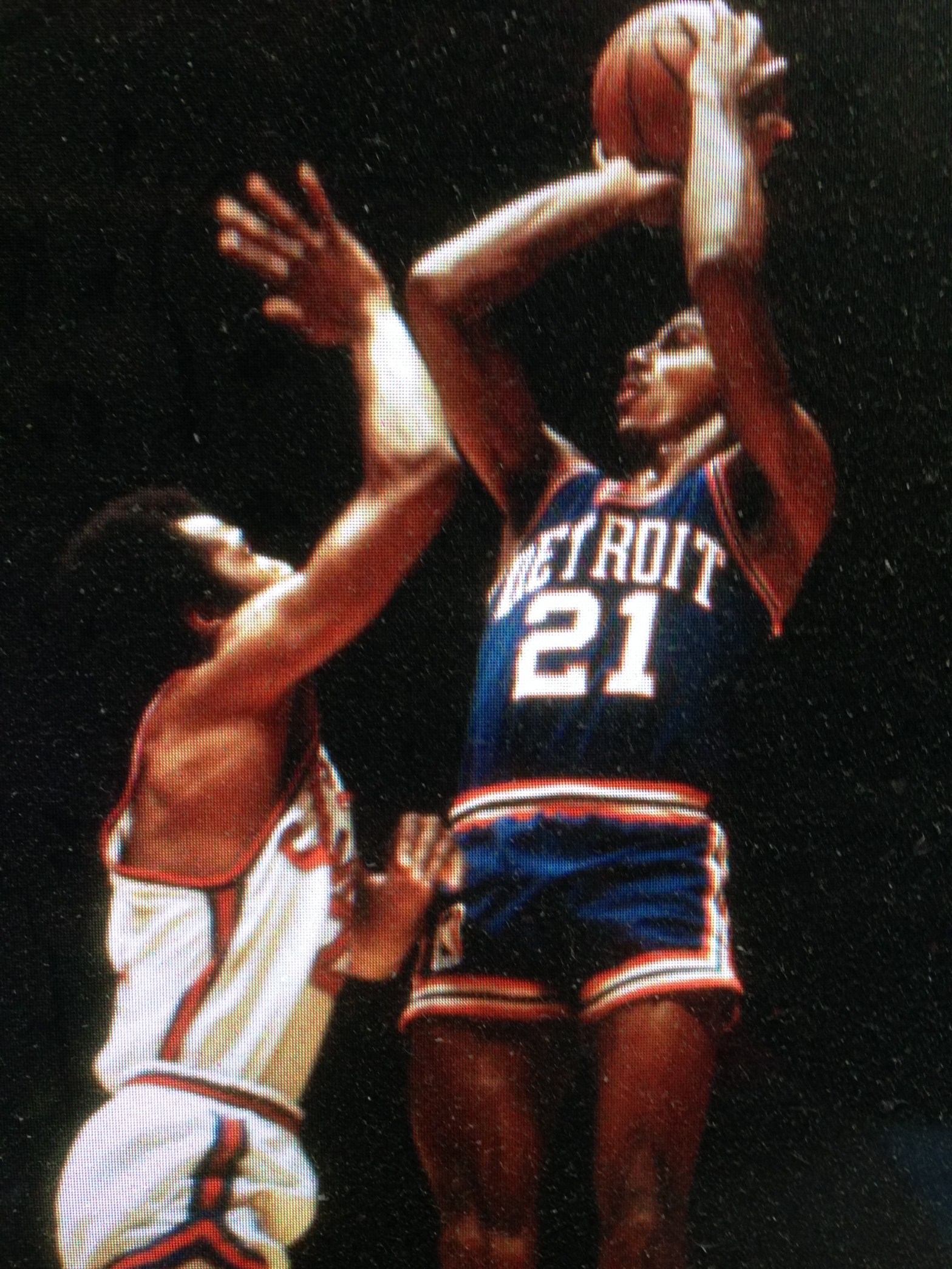

Four days earlier, Dave Bing had scored 24 points as the Detroit Pistons defeated the New York Knicks, 91-84, in the NBA opener at Madison Square Garden. During that game, Bing suffered from blurred vision, the condition caused during an exhibition game a week earlier when Happy Hairston of the Los Angeles Lakers had inadvertently poked the Pistons’ All-Star guard in the right eye.

Concerned because the injury did not heal quickly, Bing had visited a specialist when the team returned to Detroit. The news had not been good. Now he lay in bed at the University of Michigan Hospital waiting for doctors to remove the bandages from his eyes. On October 15, a three-man team of surgeons had labored six hours to repair a partially detached retina.

As Bing waited, a million thoughts raced through his mind. What if he were blind? What if he wouldn’t be able to play basketball again?

Finally, the doctors who had had to bandage both eyes to prevent Bing from moving the muscles in either, slowly began to unwind the bindings.

“I saw a light,” Bing later recalled. “It really hurt, I can’t explain it. It’s a heckuva feeling but the light hurt my eyes. I guess I didn’t realize what it would be like at first.

“I was 12 hours without sight. My wife and a friend had to lead me around by the hand. People don’t realize how lucky they are just to have sight.”

Since that day, Bing has returned to the Pistons and resumed his role as the team’s captain and floor leader. Last season, he helped lead the team to its best year in history. Detroit won 52 games, the fourth best total in the NBA, and carried the rugged Chicago Bulls to seven games before being ousted (by two points in the last game) in the first round of the playoffs.

His comeback is truly one of the most dramatic stories in sports history. Considering Bing’s ophthalmic history, it is remarkable that he is able to play basketball at all, let alone compete with the world’s finest players in the toughest pro league around.

A childhood injury—he punctured his left eye with a nail protruding from a makeshift hobby horse—had reduced the vision in his left eye. His eyesight, with corrective lenses, is about 20-50. Without glasses, many doctors would consider Bing legally blind.

During games, Bing wears is a single contact lens in his right eye because that is his lead eye for shooting. Still, he moves in a shadowy world of flashing figures on the court, recognizing teammates by their size and by the color of their uniforms.

“I can still see with the contact lens,” said Bing, entering his ninth pro season this year. “But my peripheral vision isn’t as good. When I had the one good eye, I could always pick people up on the fastbreak. I can’t pick them out like I used to. Now I pick out uniforms. I see a flash and go for that. It’s not like giving the ball to a guy you recognize.”

Nevertheless, Bing ranked fifth in assists among NBA guards last season and still managed to average 18 points a game. He was named to the All-Star team for the fifth time.

Obviously, Bing no longer is the slashing, hell-for-leather player who dumbfounded teammates with his slick passing as the NBA’s Rookie of the Year in 1966-67, or the deadly outside shooter who became the first guard ever to lead the NBA in scoring in his second season. However, in many ways, he is a better all-round ballplayer now than he was before the injury.

“In the hospital, just lying there, I would think of a million and one things,” recalled Bing. “I realized it could happen (he refuses to use the word ‘end’) but I put it into the back of my mind because it was the last thing I wanted to happen.

“I thought of the things I would have to do to adjust. But even though you try to prepare yourself mentally, it was more obvious to other people than to me that I wasn’t the same player. It was a while before I realized I couldn’t do the things I did before. Without a doubt, I don’t shoot as well as I did. And I don’t play with the same flair.”

Bing could have sat out the entire 1971-72 season. But he didn’t. Instead, he relentlessly questioned the doctors until allowed to play. “Any athlete is competitive, and basketball is my livelihood,” he explained. “If I can’t perform, I’d lose that. There is no way I would have been satisfied sitting out. It would have been a heavy mental thing. I had to find out for myself right away. But I’d say it took a year to fully adjust.”

Bing was back in the lineup in less than two months following surgery. He averaged 22 points and six assists in the final 45 games of the 1971-72 season. But he discovered he would have to make even more adjustments. Bob Lanier, a talented 6-foot-11 center out of St. Bonaventure, was rapidly blossoming into a superstar in his second pro season, and Jimmy Walker, who picked up the outside shooting burden in Bing’s absence, was playing well enough to make the All-Star Game that season.

“I had to adjust to them, too,” Bing said. “I just couldn’t go out and start shooting. Then, when Ray Scott took over as coach, I had to adjust even more. He got away from the wide-open offensive game and played more defense. It worked and I’m not such a hard head that I wasn’t for it.”

When Scott became head coach, replacing Earl Lloyd early in the 1972-73 season, Bing already had overhauled his game and mental attitude. “I started taking different (more conservative and less frequent) shots. If you let down in one area, in order to make up for it, you have to perform in other areas. I feel if I had to score 25 points a game again, I think I could. We probably wouldn’t win because we wouldn’t be a good unit that way. It’s the same with Bob [Lanier]. He could score 30 or 35 points a game if he wanted to shoot.”

With Bing averaging 22 points and seven assists, Scott brought the Pistons home in third place in the rugged Midwest Division. The 1973 Pistons won 21 of their final 30 games, setting the stage for their brilliant playoff run last season.

With the baseball Tigers, football Lions, and hockey Red Wings all experiencing major letdowns after riding high with veteran teams through most of the 1960s, the Pistons suddenly became the hottest item in a sports-hungry town. No longer the doormat of the NBA, Scott’s hustling ballclub made the playoffs for the first time in six years.

Only two players, Bing, now 30, and 33-year-old backup center Jim Davis, are older than 26. Detroit began to win with regularity, and the fans turned to basketball. The Pistons averaged better than 7,000 fans for 41 home games, and more than 5,000 fans began to line up at 6 a.m. outside Cobo Arena, the team’s homecourt, when playoff tickets went on sale last spring.

General manager Ed Coil got coach Scott the players he wanted to go with Bing and Lanier. Coil used draft choices to trade for forwards Don Adams and George Trapp, guard John Mengelt, and Davis. Rookie guard Chris Ford, a defensive specialist from Villanova, fit right into Scott’s concept of team defense.

Veterans Curtis Rowe, Willie Norwood, Stu Lantz, Lanier, and Bing we’re already on hand to help the younger players, rookie Ben Kelso and forward Bob Nash. Scott turned them into a hard-nosed, defensive-minded club that gained the respect of every team in the NBA.

“The Pistons could always score.” said one rival coach. “But if they got behind early, they’d give up. Now they keep coming at you, no matter how far behind.”

Bing’s floor leadership and vastly improved defense have become an integral part of the team’s new spirit. Never a firebrand, Bing leads with quiet dignity. He believes in personal, man-to-man discussions rather than locker room tirades and continually keeps his teammates loose with good-natured, often raucous kidding.

“David gives us a third dimension,” says Lanier. “He’s a joker, a prankster. He keeps us relaxed. He’s the floor general and the captain.”

Bing is the first to compliment a teammate for a good play. But he never criticizes a teammate in public. To Bing, leadership is a highly personal thing. It is something that must not be abused.

“The first and most-important thing is to have rapport with your teammates,” he said. “No matter how much talent a team has, it can still be a bad team without rapport. Most of us are very, very easy guys to get along with. Some guys came here as individuals. But we changed them. And every guy, all the way down to Ben Kelso, has to feel important. Each guy is one-twelfth of the team. It’s not just me and Bob.

“Every guy on this team considers me a friend. I’m easy going, and it just happened, I guess. But it helps us play better.”

When the Pistons lost Lantz to New Orleans in the expansion draft, Bing was deeply concerned. “We’ll miss Stu,” he says. “We won games with him, and we won games without him. But he’ll be hard to replace.”

Ever since coming to Detroit as an All-American out of Syracuse in 1966, Bing has devoted a great deal of his spare time to promoting basketball and other civic projects. His only regret is that he hasn’t been able to spend as much time as he would like with his wife, Aaris, and three daughters, Cassandra, 10; Bridgett, 8; and Aleisha, 5. He has spoken at numerous banquets, worked with the Boys Club of Metropolitan Detroit, the YMCA, a high school boosters’ club and, along with former Red Wings’ star Ted Lindsay, helped chair the fund-raising drive for the Metropolitan Association for Crippled Children (March of Dimes).

Bing’s major interests are Big Brothers, a program designed to provide a one-to-one relationship for boys without a father figure in the home, and a series of basketball camps he operates in the offseason. For six years, Bing, who has no sons, has been a “big brother” to Richard (Rickey) Gilmer, now a 19-year-old freshman at Oakland University, near Detroit.

“I really feel I’ve helped him a lot,” says Bing. “He comes over to our home all the time for dinner. A lot of people lend their names to programs. But I like the one-on-one relationship Big Brothers offers. I’m very proud of Rickey.”

Unlike many athletes, Bing is always on hand for his summer basketball camps in Michigan and Pennsylvania. He regularly sends boys from that Big Brother program to the camps and hires high school basketball players from the Detroit area as counselors.

“I’m not in it for the money,” said Bing. “Oh, we make a profit, but I make enough from basketball to carry me over. At most camps, the pro only makes a couple of appearances all summer. I feel it’s a fraud if I’m not there. And it does a lot for me. You watch a kid grow, not only as a ballplayer, but as a person. I want them all to remember that and help others when they get the chance. That’s how these things snowball, and that’s how we can make a better situation for all of us.”

Bing is proud that some of his former pupils and camp counselors have become pro basketball players. Ralph Simpson, Denver Rockets; Roland Taylor, Virginia Squires; John Brisker, Seattle SuperSonics; and Michigan’s Campy Russell, recently drafted by the Cleveland Cavaliers, all were Bing campers as was Vanderbilt’s Billy Ligon, a rookie with the Kentucky Colonels.

“It helps to have an understanding wife,” said Bing. “So, I spend as much time as I can with my family. The girls are too old to take to a boys’ camp now. So, I’ve given up golf to spend more time at home.”

At the basketball camps, Bing puts in a 14-hour day. He often sits up late at night with his counselors, conducting bull sessions he finds mutually beneficial. Now in the second year of a $750,000, three-year contract, Bing hopes to retire as a player within three years.

“Physically, I could play longer,” he admits. “But I don’t want to leave struggling. I want to go out with fond memories.”

He recently purchased a new home in a Detroit suburb and, through careful investments in real estate and his basketball camps, has assured the future financial security for his family. “I wasn’t real happy when I first came to Detroit,” Bing admits. “But the town has grown on me. I want to be the first basketball player to begin and end his career in Detroit. Basketball has been good to me. I’ll never have to go out and work if I don’t want to. My family is taken care of. I eventually want to do things for other people, especially young people.

“Of course, I don’t want outside business or other things to interfere with basketball right now. That’s still my job. But a pro career is short and depends so much on good health. You look around the league and see how many guys get poked in the eye. What happened to me was a freak accident.

“I’ve had a chipped patella in my knee and a nagging groin injury over the last couple of years. But, except for the eye injury, I haven’t missed many games. No one knows how much injuries hurt, except me and the trainer. Sure, I can play maybe three more years. But if anything happened where I could not perform, I’d give it up.

“Right now, I’m looking forward to the new season. It looks like I’ll be on a good team the rest of my career. We were young, and we’ve got a chance to win the championship. I really believe that.

“I’ve been part of all the bad years in Detroit. You can be damn sure I want to be a part of the good ones now.”