[Several years ago, I got into a conversation with a guy at a holiday party. I’ll call him Ron. We’d never met, but Ron had a real gift of gab and, well, I’m an easy listener. A few wild-and-crazy stories later, Ron said that something or other reminded him of the time he worked construction in Philly. He then proceeded to tell me an amazing story about the time he met Julius Erving. I walked away thinking Ron was telling the truth. But who knows? I filed away the story in the back of my head, where its stayed.

Well, a few weeks ago, I drove into town and picked up the mail at the post office. As I walked out, heading in was Ron, maybe 10 years older and with the same distinctive long white beard. I re-introduced myself and mentioned that we’d talked at so-and-so’s party. He remembered the bash, and I asked him to retell me the Julius Erving story. No problem. He repeated the same story, same details, same matter-of-fact demeanor. He could have been giving me directions to the local 7-11.

I’m going to repeat Ron’s story here, now 98-percent confident that it’s true. Ron said back in the 1980s he and about 10 other workmen were renovating a house in one of Philadelphia’s upscale neighborhoods. It was your typical scruffy work crew that had the radio and power tools blasting non-stop. The foreman appeared one day and asked to have a word with Ron. “Tell the guys to dress up tomorrow. Nothing grungy, okay?” Ron shrugged sure and spread the word.

Around noon the following day, the foreman materialized again and told everyone to tuck in their shirts. He said Julius Erving lived next door, and the Doctor was throwing a party. Everyone was invited. As Ron explained, rather than ordering the workmen to keep it down for the afternoon, Erving simply invited them to his party. No tension, just total class.

Ron said he cut through the tall shrubs to Erving’s house and opened a side door that happened to be the Doctor’s own indoor basketball court. Ron stepped inside, and there was Larry Bird shooting baskets. (Okay, this detail sounds too good to be true, but who knows?) Ron said he and his work buddies hung out for a couple of hours, smoked lots of cigarettes, met all the big shots in attendance (including the Doctor), and then called it a day. And a damn-good story, too.

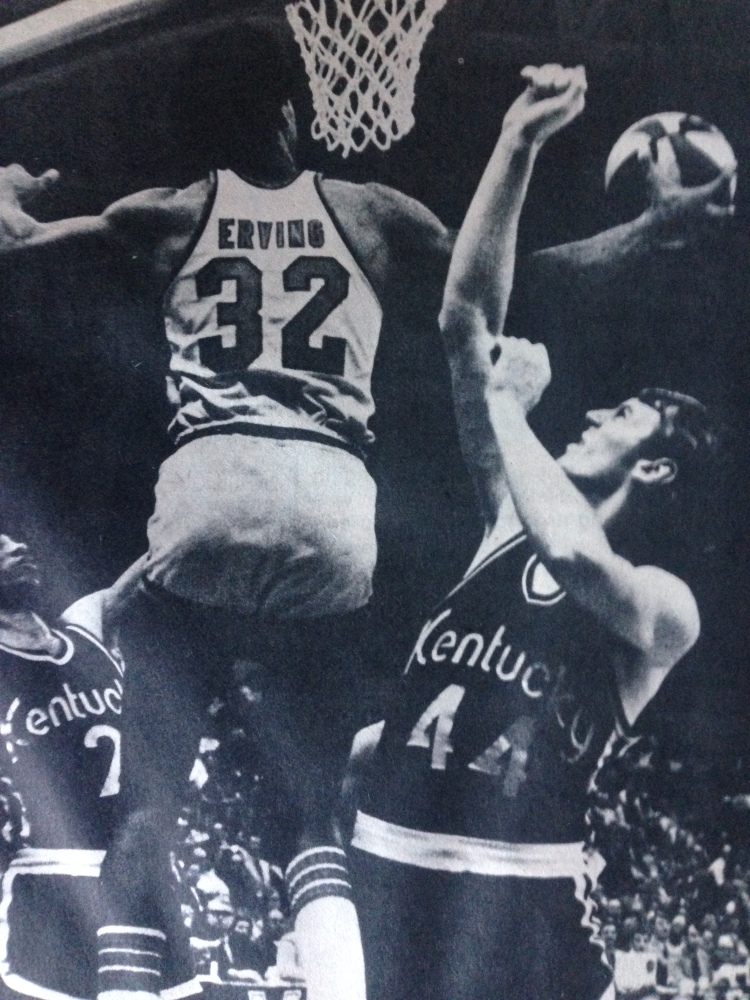

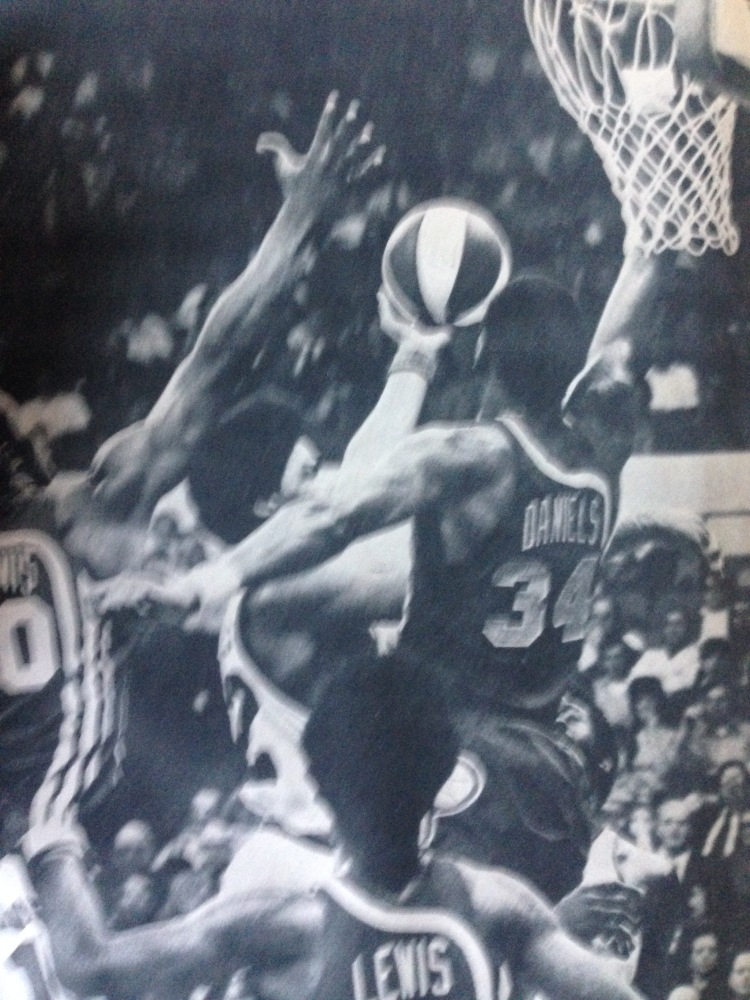

I mention all of the above as a reminder: Julius Erving has always had a certain grace and humanity about him. Those qualities are on full display in this quick read from New York Post writer and then-reigning ABA national columnist Jim O’Brien. The story appeared in the magazine Pro Basketball Illustrated, 1973-74, right after the Doctor was traded to the New York Nets. Enjoy!]

Julius Erving was at ease, free at last, he felt his 6-foot-7 body stretched out, all arms and legs, it seemed, on a grassy slope outside the Roosevelt Park playgrounds, where he’d just been playing a series of two-on-two basketball games one night this past summer.

Earlier that day, the New York Nets had announced that, through a series of payoffs, they had acquired the rights to Erving from the Virginia Squires of the ABA and the Atlanta Hawks of the NBA, who’d both been to court to see whom he’d be playing for. Now he was a Net, signed to an eight-year contract calling for something in the neighborhood of $2.5 million. And here he was, back home again at Roosevelt Park, just 15 minutes down the highway from Nassau Coliseum, where he’ll be playing for the Nets this season, going against his old buddies strictly for fun.

“Stick it, Doctor!” kids had been crying out as the young man they call Dr. J., just 23, played a half-hearted halfcourt game, in which he seldom showed off all those moves and slam dunks that separate Dr. J. from the pack in professional basketball.

Lou Carnesecca, who coached the Nets for three years before returning to St. John’s, had a chance to sign Erving after his junior year at the U. of Massachusetts, but didn’t as a matter of principle. He describes Dr. J.’s style of play as well as anyone. “He creates,” says Louie. “It just flows out of him. He has great imagination on the court. You can talk about this guy like a poet. He is a poet, an artist.”

Erving would appreciate that. He thinks he brings a certain flare to the game, an excitement it needs, and the Nets did not hesitate when they got a second crack at him. “Julius has come home,” Nets’ owner Roy Boe had said earlier that day, “and he’s come home for good.”

Now Erving had extended his long, lean frame on the grass, relaxing and allowing his words to flow in the same smooth manner in which he does his thing on a basketball court. “I’m not a very difficult person to please,” said Erving, for beginners. “My job allows me to go a lot of places and do a lot of things seven months of the year. In the offseason, I’m content to do nothing, to do the simple things of life—like lying out here in the grass.”

A cream-colored Lincoln Continental Mark IV, with a stereo tape console inside, which Erving had parked nearby, would seem to offer an argument to what Dr. J. has just said, but he didn’t think so. Perhaps if he had parked a private jet, like the one Arnie Palmer pilots, he’d have thought that an extravagance.

Erving was hot, he’d been playing ball for several hours and he moved when he heard the bell ringing of the Good Humor man. He went to the fence, and asked for several kinds of ice cream concoctions, being told each time that none was left. Finally, the young man sitting nonchalantly in the window of the truck, said, ‘Why don’t you get in that Mark IV and go to the grocery store? You come around here jiving us . . . “

Julius just laughed, considering the source, and took a chocolate-covered ice cream. Soon, it started melting in his large hands. “He’s not selling very good ice cream,” he said with a smile, before depositing the remaining mess into a nearby trash basket with the most pedestrian stuff shot he’d ever attempted.

“When I came over here today,” Erving went on, “a lot of guys had heard the news about me signing with the Nets, but no one was crowding around, jumping up and down. I wasn’t exactly that worked up about it myself. Do I look excited?”

That’s the pity of it. Erving looked as deadpan as he did that day before a platoon of reporters, photographers, and TV cameramen. Today it’s difficult to find a well-paid pro basketball player who’s excited about his good fortune. It seems somehow to be a shame.

“I’ll never help a player again to negotiate a pro contract,” said Al McGuire, the Marquette coach, who helped Jim Chones jump to the Nets the year before. “That’s what he wanted: to play pro ball, to have a Hog (Cadillac), the big money for him and his family. Now he’s got it, and he’s the unhappiest damn kid I know.”

Chones didn’t come through in his first season with the Nets. Erving was an instant success, however, with the Squires. He averaged 27.3 points and 15.7 rebounds as a rookie on a team that had Charlie Scott as a scoring leader. His 34.6 points per game average was the ABA’s best. With those sort of statistics, Erving was told he’d sold himself at bargain basement prices when he signed a four-year contract for $500,000, much of it in deferred payment, when he quit school. So he signed with the Hawks at higher figures. That’s when life got more complicated.

“I hope that’s all behind me now,” he was saying this warm summer night. “This should eliminate a lot of hassles and strains.”

He said he would’ve played in Virginia, if the courts said he did, but had been looking forward to life in Atlanta. “It was the kind of young, progressive city I hoped to build my future in,” he said. “I never had any reason to believe I’d be back in New York. Being home hasn’t really hit me yet. I figured there was no way I’d ever be back in New York.”

The Knicks had tried to get him, but couldn’t for some reason, resolve all the problems necessary to secure his services. With an aging team that needs to be built up again, Erving’s loss was a serious one for them. Now the other team in town has a superstar with huge box-office appeal, who figures to tug away some of their Long Island fans, and some possibly from Queens and even the Brooklyn boroughs.

Did Erving need the big-time to feed his ego, feeling perhaps that he’d suffer the sort of way Henry Aaron did by playing in towns where he didn’t get much national publicity? “No, I don’t feel that way,” said Erving. “All during my basketball career and life, the acknowledgement of me has been in a very limited sense. I wasn’t an All-America in high school. In college, I made All-America after my junior year, but there wasn’t much build-up, and I was only third team or something like that. I’m used to not being in the spotlight in a big-league way.”

Erving said he supports a sister who has two children, and his mother and stepfather with the money he makes. He’s buying a house for his mother, who supported him after she left her first husband with a welfare check and the money she made as a domestic, cleaning other people’s homes. He said that his mother was much more excited than he was about his coming home to play pro ball.

A lot of New York basketball fans shared her enthusiasm. Her son is something special, and they were anxious to see him play for a local team. After all, he’s one of the most-exciting players in pro ball, and the year before he averaged 31.9 points to lead the league in that category. He was also sixth in rebounding, third in steals, seventh in blocked shots. His shooting percentage was .499, which was close to the top 10, as was his total of assists. According to Steve Harriman, the Squires’ publicity man, he was a P.R. man’s dream. “He even answered all his own mail,” said Harriman.

Erving said he didn’t need all the money he was getting from the Nets, but he was not about to turn any of it back to Roy Boe’s bank account. “The only reason I did what I did,” he said, “was because that’s what professional basketball is all about. I’d never kill anybody or hurt anybody over money. I’m making more money than I’ll ever have any use for. I don’t have a capitalistic attitude: make all you can, and screw the other guy, rip the owner. I love the game. I love to play. I’d play for free if everybody else did. But when in Rome, do as the Romans do.”