[In the pantheon of NBA players short of stature, Charlie Criss still stands tall more than 30 years after sinking his last jump shot with the Atlanta Hawks. The 5-foot-8 Criss spent all or part of seven seasons in the NBA. Not bad for a guy who didn’t take his first NBA jump shot until age 28.

For Criss, his belated start had everything to do with breaking down the barrier that NBA players under six feet were defensive liabilities. After a few failed attempts to make an NBA roster after college, Criss kept his dream of playing in the pros alive in the Eastern League. His big break came when Hal Wissel, a scout for the Atlanta Hawks, wandered into an Eastern League game that included Criss’ scrappy Scranton Apollos. An hour later, Wissell was on the phone with then-Hawks’ coach Hubie Brown to implore his boss to take a look at this kid known as “The Mosquito.”

Brown had already seen The Mosquito in action in New York. He agreed that Criss was a special talent. But he’d get killed on defense. “I told Hal Wissel that Charlie couldn’t stop anybody,” Brown recalled the conversation, “and he said no one could stop Charlie.”

Brown relented—and soon realized that Wissel was onto something. In this article, published in the Atlanta Constitution’s Sunday Magazine on November 20, 1977, writer Michael Hinkelman tells his readers around Georgia about the Hawks’ exciting 28-year-old rookie, then the oldest rookie in league history]

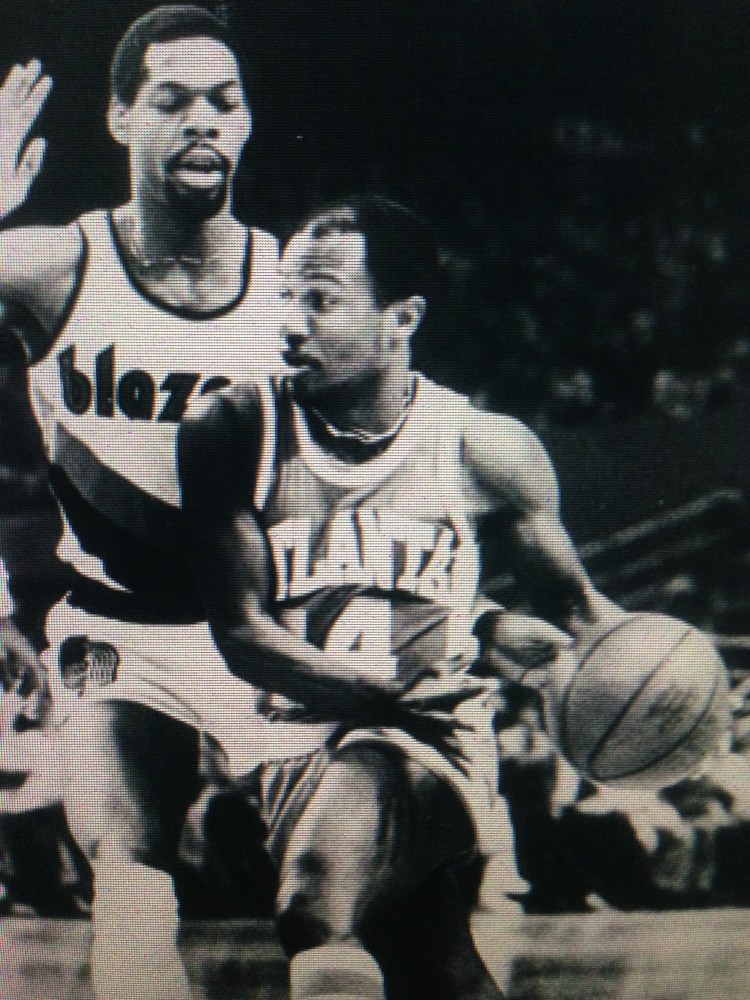

One afternoon at the Omni recently, just before they lifted the lid on yet another campaign, I watched the Atlanta Hawks work out. I noticed one player in particular. Never mind the fact that he was the smallest player on the court, and only 5-foot-8 inches at that. He had the polish and the sense of the game and that special feel of the ball that can come only by growing up with it. Bouncing it, and shooting it against somebody else good almost every day of the year. He was almost sure to have learned the game on the hard and hot surface that is universally recognized as basketball’s gut-and-soul home: the playground.

His name, I later learned, is Charlie Criss, and at the venerable age of 28, he is the oldest rookie ever to play in the National Basketball Association. He won his spot on the Hawks’ roster almost entirely on the strength of his ability and efficiency: during the preseason and in scrimmages, Criss moved the ball, he scored, he directed traffic, he was in charge. In Criss, one sense is a roundball equivalent to Rocky Balboa, the aging South Philly pug who gets a shot at the heavyweight title and gives it all he’s got.

Indeed, there is a lot of Rocky in Charles Washington Criss. Like the Italian Stallion, Criss is unsparing of himself in training, both in season and off, displaying an up-by-the-bootstraps striving toward self-made excellence. Charlie Criss’ arrival in the NBA has hardly been sudden, nor has it been easy either. Until he started on the backline for New Mexico State and helped lead that school to three consecutive appearances in the NCAA regionals, nobody much outside of the black communities in Harlem and South Philadelphia and Las Cruces had heard of him. Even after his tenure at New Mexico State began to lift him out of obscurity, many pro scouts still tended to dismiss him as a nickel-dime fancy gunner. What’s more, he was too damn little. Charlie Criss in the NBA? Why, the mere thought of it was a burlesque. Basketball pays off only in the big leagues, and nobody was much interested in Charlie Criss.

This sort of initial rejection has been the pattern of Criss’ life. Pudgy as a boy—he grew up in Yonkers, 10 miles north of Manhattan—he had been embarrassed when he failed to make the team as a ninth grader and was shamed into making it in this sport. “Of course, once I started, it was every day, 10 to 11 hours a day in the hot summer, with maybe just a break for lunch,” he recalls. “I remember, lots of times I would come home with a sore shoulder—right in here—from shooting all day. It sounds like the same old story, the All-American boy, but that’s really the way it was.”

Criss shakes his head as he swallows from a glass of beer. “You don’t see that anymore that way,” he says, “kids playing all the time. It’s different. Now everybody’s a lover.”

After graduation from Yonkers High School, Criss journeyed West to New Mexico State, where he teamed with Jimmy Collins and Sam Lacey, the latter now a starting center for the Kansas City Kings. When the pros failed to come calling, he hung around New Mexico for two more years, playing AAU basketball. Then he came back home to New York. That was in 1972, and for a while he worked in a bank, then there was a job with the Yonkers recreation department, and finally a position as a data-processing clerk with Tuck Tape Company. “That just made me realize how much I hated working,” Criss says now, smiling, but not so much humorously as clinically. He is most often that way, very direct. He does not waste motion.

Although he had failed to make the grade in the NBA, Hawks’ coach Hubie Brown remembers that he and other pros had long known about Charlie Criss. They had gone out of their way to see him play when he was something of a sovereign in the all-pro Baker and Rucker leagues, the toughest summer wheels in the country (the former in Philadelphia, the latter in New York). Both leagues floated to various locations, but no matter, Criss was always a fixture.

The significant focus of all the summer competition in New York is the playground behind the fence on 138thStreet off Fifth Avenue. Audiences here are appreciative and quite knowledgeable; they are quick to detect the spurious move and overblown reputation. All of the big names—Dr. J., Tiny Archibald, Elvin Hayes, David Thompson, among others—drop by periodically to show their mettle. In fact, much of the appeal of the Rucker pro tournament has come from witnessing a team of local favorites who never really made it stay even with a group of well-known pro players. News of the have-nots’ successful exploits at the expense of the established NBA stars quickly gets around.

For his part, Charlie Criss says he was never held under 30. It was seldom that Criss disappointed his followers and often there was a special treat for them, as the time a couple of summers ago when Criss and Tiny Archibald got into a shootout one night and ended up with about 100 points between them. “We were dueling,” Criss remembers. “Archibald would come down and hit from the top of the key. Then myself, top of the key. All long shots—first the top of the key, then the corners. It was the best duel I’ve ever been in.”

In time, Criss became known as “The Mosquito,” and it was not a phony alliterative or geographical title invented by a P.R. man. It was a high sign to Criss that even though there were guys on the playground nobody ever heard of, many of them could hold their own with the best in the NBA, and it was just a simple matter of getting the right breaks.

So Criss took his act to the Eastern Professional Basketball League, making stops first in Hartford, Conn., then Cherry Hill, N.J., and finally Scranton, Pa., where he played the past two seasons. In four years in the Eastern League, Criss became its most-prolific scorer in history (a cumulative average of 34.1), leading the league in scoring three consecutive years, and thrice being named its most valuable player. Two of the four years, his teams won the league championship.

The Eastern League is almost a story itself. I know. I grew up watching it, and it was always a big treat to go see the Williamsport Billies play on a Saturday night. Only a handful of its refugees have ever made it to the NBA (Bob Love, Ray Scott, Bob Weiss), of whom Criss is the latest.

Most of the players hopelessly chase rainbows: men whose legs have gone back on them, along with their hairlines; 175-pound forwards who would be gobbled alive by the swift, brutal Brobdingnagians of the NBA; chubby centers whose only credentials trace back over four or five years to their local high school teams or to a season or two of service ball with the Fort Desperation Spastics.

Then there are men like Charlie Criss, who doggedly cling to the past. For them, the most terrible of sound is the whistle that ends the game.

Charlie Criss got $60 a game—that included gas, food, and lodging—and played two games a week (Saturdays and Sundays) for four months. Eastern League basketball was guts-and-elbows basketball that put a premium on bruises. He played in dimly lit high school gyms. The fans there often exhibit a certain kind of derisiveness that can get under a man’s skin. Criss knew that the two-dollar sports were safe in the stands, with blondes by their sides and strong waters in their jugs, sneering at him: “get the midget off the floor,” or “not bad for a little squirt.”

And when the games were over, the players could look forward to a postgame meal of cheeseburgers, a car ride (usually your own car) through several 100 miles of boonies, and Monday-morning jobs as pipe fitters, school teachers, barbers, salesman, and dental lab technicians. In the Eastern League, everything comes hard: finding a practice area, meeting a payroll, drawing a crowd.

Saturday night at Scranton in winter time is not much fun, even if there isn’t a foot of snow on the ground. A crusty community of 100,000 nestled in the anthracite coal-mining region of northeastern Pennsylvania, it is less pleasant for all the soot that permeates the air.

But to hear Charlie Criss talk today, you would think that the Eastern League is some sort of panacea. “The Eastern League was good to me. If I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t be here now,” he says. “For the most part, the fans in Scranton were good to me. They told me I should be in the NBA, but they wondered how I would survive in the land of the giants.”

Why did he languish in the Eastern League for four years? “For the love of the game. Not over three or four play for the money. We play for the love of the sport—the love of contact.”

Unmarried, and with a studied intention to remain so for a while, Criss lives in as easygoing a manner off the court as he appears loose on it. “He’s a good person, one of the most even people I’ve ever met,” says Hubie Brown. Criss is not instinctively avaricious. In fact, his wardrobe usually consists of a T-shirt, khakis, and sneakers. He doesn’t even have a car.

“I’m not eaten up with comforts,” he concedes. “I just love basketball enough that I’d play it in hell with my back broke. There were times I thought I’d never get a chance to go up to the NBA. Still, nothing satisfies that ol’ basketball bug but playing the game. You just got to play.”

Last year, Criss welcomed a tryout with the New York Knicks, but was cut just before the first exhibition game. For the first time, he had reservations about whether he would ever make the NBA. Until then, he had steadfastly clung to the notion that someday some bigwig in the NBA would discover him.

“I began to wonder if I hadn’t been kidding myself all along. When that worm of doubt starts eating at your guts, it’s pretty miserable, especially late at night.”

Let it be noted that the Knicks never really gave Charlie Criss a fair shot, inasmuch as they had no less than six guards under no-cut contract. The Knicks’ Earl Monroe—the self-styled Doctor long before anybody ever heard of Julius Erving—told Criss before he left camp that someday he would play in the NBA. “Get with the right team,” Monroe said, “and the opportunity will be there.”

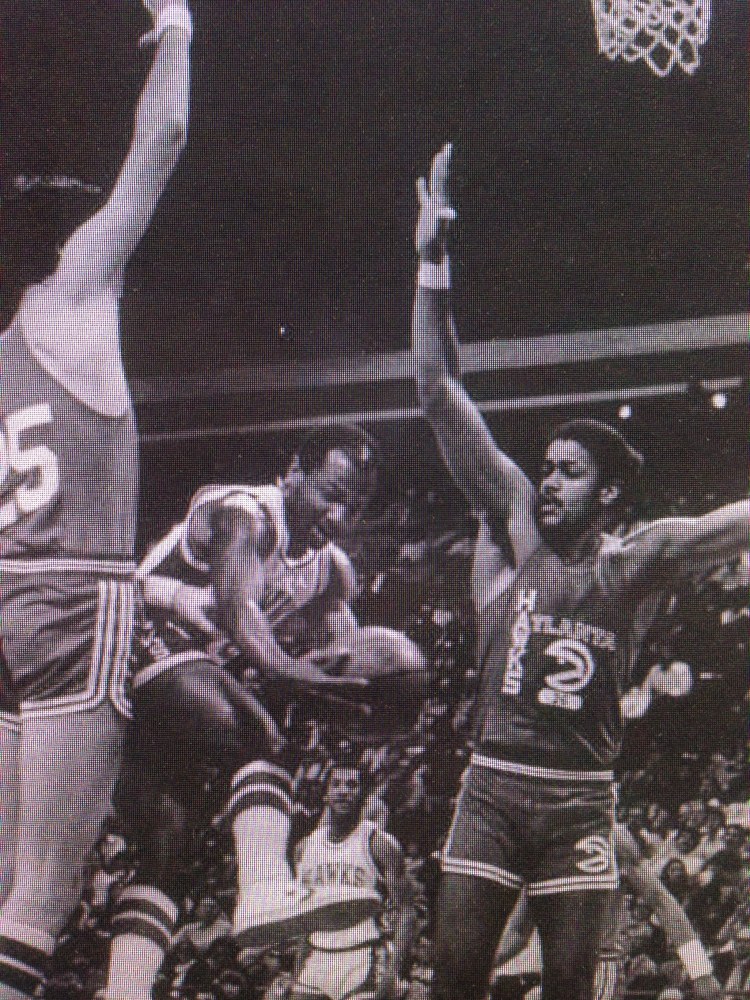

While the Hawks may operate under the impression that Criss is only a cog in the franchise, his appearance on the local scene has unsettled the order of things. He may be making the minimum (a paltry? $30,000), but Hawk fans have already warmed to him. As incredible as it might seem, Charlie Criss has garnered already that special drawing value usually accorded only to superstars. When he came off the bench in the Hawks’ home opener, his presence was signaled by a knowing murmur that swelled to a slightly pitched rattle. In 16 minutes of action, Criss scored eight points, dished off for a couple of hoops, and played tenacious defense. Toward the end of the game, the Hawks’ public-address man announced plans for the formation of “The Charlie Criss All-Stars,” which they hope to take on the road periodically, if they can first assemble a team. There are only two criteria for membership: you must be under 5 feet tall and be a consummate basketballer.

There’s evidence that Charlie Criss has indeed arrived in the NBA, but make no mistake about it, he can play. In his second game against the perennially tough Boston Celtics, Criss fired 21 points and drew rave reviews from the press. On offense, Criss must be guarded with the kind of defense that reminds most Atlantans of their favorite fall sport, football. Criss controls the ball so well the close guarding is not profitable. He employs the close defender as a fulcrum, whips around him, and scores. “I don’t believe I can be stopped,” he told me recently. “The thing is, I don’t know what I’m going to do with the ball, and if I don’t know, I’m quite sure the guy guarding me doesn’t know, either.” Criss says this not with boastfulness but in the straightforward manner in which he says these things.

Charlie Criss is, above all, a possessor of great court awareness. He will occasionally sneak a quick, but deadpan, look over to the press—the critics—after a particularly good pass to see how well the play registered. One can well imagine that soon Criss’ loyal followers will not abide watching anybody else on the team handle the ball, much less shoot it.

“That basketball floor,” says coach Hubie Brown, “well, I think that is Charlie’s world. And the louder the applause, the better Charlie’s going to be.”

That applause, folks, is no longer confined to the playgrounds of New York or the dingy arenas of the Eastern League. In Atlanta’s Omni, there is now a special reaction, and excited murmuring every time Criss gets the ball; there are disappointed sighs when he gives it up.

Atlanta is a branch town that generally has difficulty convincing itself that anything special could actually get started right here. That was before Charlie Criss checked into town. He’s a throwback to the old days when athletes put in a full day’s work for a full day’s pay.“

[BONUS COVERAGE: By his mid-30s, Charlie Criss was out of the NBA. In this article from February 9, 1985, Atlanta Constitution’s always-outstanding Jeff Denberg tells how Criss got back into a Hawks uniform one last time for more NBA games. A very nice story, published under the headline: Old Man Charlie.]

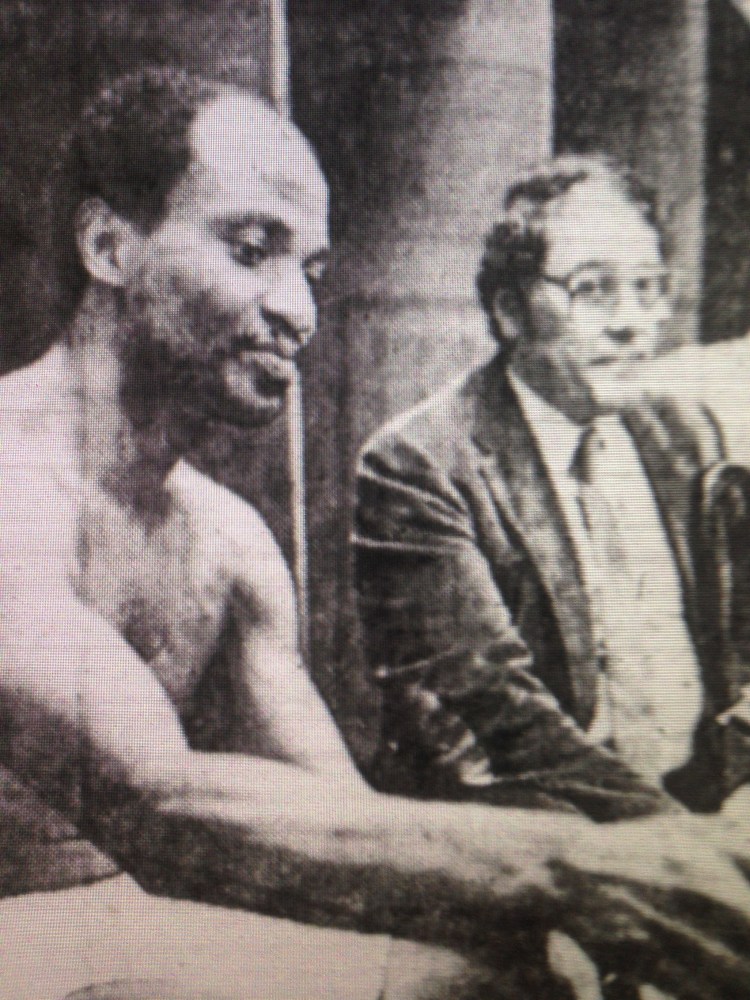

Mike Fratello, the Atlanta Hawks’ coach, was reading the numbers in the box score. He winced. “Oh, my God,” he said, whispering like no one else should know of the thing he had just done. “I played Charlie Criss 45 minutes.”

You did what? Say you beat your dog, Mike Fratello. Say you set the cat’s tail on fire. But don’t tell us you subjected that little old man to 45 minutes of an NBA game.

Fratello peeked around the corner of the dressing room, eyes searching for bald, 5-foot-8 Charlie Criss. And there was Charlie, pulling up his socks, grinning. “Yes, indeed, yes, indeed, this was great,” Criss said, having just played 45 minutes in the Hawks’ 94-91 overtime win over Milwaukee on Thursday night. Had a great time, Criss said. He laughed. “I feel fine. Real good.”

Gym-rat Charlie claims to be 36. Entered junior college in 1966. Three years of college, three in the Army, five in the Eastern League. Signed with the Hawks in 1977.

Two kids, maybe 12 years old, stood by the scorer’s table Thursday night and watched him warm up and one said, “Hey, look at the little guy. Dig that guy. Do you believe him?”

Cut loose by Milwaukee in November 1983, brought out of the sales office by the Hawks in February 1984 for nine games, recalled from his commentator’s seat at the press table Wednesday. How do you not believe Charlie Criss?

Tuesday morning after a telecast in Philadelphia, Criss asked, “Are they going to replace [Hawk] Doc Rivers on the roster? Are they going to call up a CBA guy?” [referring to the minor-league Continental Basketball Association] He shook his head in negative reaction to such news. “I can help them,” he said, eyes piercing, pride talking. “I know the system. I can still play the game. No kid is gonna help them.”

Fratello rolled his eyes at the news. “Could be,” he said. “Could be.” A day later, could be was. The league’s shortest and probably oldest citizen was back in the NBA, at least through next week’s games in Denver and Utah.

Surely, by now you know the Hawks played most of the week without their starting guards, that they were without five regulars when Scott Hastings went home Thursday to be with his pregnant wife. You heard Fratello sent out nine players, including 10-day temporaries Criss and Stewart Granger, to play a Milwaukee team that had recently fashioned nine and 11-game winning streaks.

And you know that under highly improbable circumstances, the Hawks rallied from 23 points behind with 16 minutes to play, forced overtime, and then won 94-91.

Charlie Criss had seven assists, five rebounds, and two points in this game. He only got two breathers, one at the start of the second quarter, the other in the third quarter when Fratello had to worry for little Charlie’s safety. “They really worked him over,” Fratello admitted later.

The third quarter read like a cheap movie script on mob violence. Here is has-been Charlie Criss coming out of retirement and Don Nelson, the big boss, who once employed him in Milwaukee, sending his best henchmen to take him out.

Four times in fewer than 3 ½ minutes, Sidney Moncrief and Craig Hodges or Moncrief and Paul Pressey doubled Criss at midcourt, surrounded him and—figuratively speaking—pummeled him and held him by his ankles to shake loose his change as the score mounted to 63-42 against the Hawks.

Wildly, Charlie looked for help that wasn’t there and wasn’t coming. “I told Witt (Randy Wittman), please don’t turn your back on me,” Charlie said. But all he saw were red-shirted backs and white-shirted chests.

Almost apologizing, Wittman said he could not help. “My legs were gone.” In four games over six nights, he worked 46, 38, 41, and 40 minutes, and as soon as he left the court Thursday, Wittman packed his surgically repaired left knee in a great wad of ice to ease the discomfort.

It was 71-48 when Criss came back for what would be 20 minutes, 39 seconds of unrelenting action. “By now, I had told the guys to get down the floor and take up their positions so I could have room to operate,” he said. He kept the ball safe after that. The Hawks rallied furiously to cut the deficit to 14 after three quarters, 10 with eight minutes to play, then five, three, and the ties that forced overtime at 85.

They won because Dominique Wilkins and Kevin Willis and Rickey Brown, all young and strong, went furiously for the hoop, flying into the face of the Bucks for their baskets. But they could only do that because Criss got the ball up the floor safely and allowed them to operate.

And before you run to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Old Men on Short Contracts, be advised of this: the box score exaggerates. A recheck shows that Charlie Criss did not play 45 minutes. He played only 43:01, just three minutes more than anyone else.

Fratello can relax.

EXTRA BONUS COVERAGE: How about the night that Charlie Criss scored 72 points for the Scranton Apollos in an Eastern League game? Here you go. The coverage is from the Scranton Tribune, with a few choice lines plucked from the Scranton Times-Tribune and the Hazleton Standard-Speaker to round out the story. The article ran on January 26, 1976.]

The Hazleton Bullets got caught in the “Criss”-fire Sunday night. Dynamic playmaker Charlie Criss put on a record-smashing 72-point performance Sunday night to power the Scranton Apollos to a 133-131 conquest of the Hazleton in double overtime as the Eastern Basketball Association leaders chalked up their 10th win in 11 games.

The amazing scoring show by Criss eclipsed the 14-year-old record set by Wally Choice, who pumped in 69 points while playing with Trenton at Sunbury on March 3, 1962. The closest anyone came to Choice’s mark before Criss’ record-shattering effort was Tom Stith with 67 while playing with Allentown at Johnstown on December 19, 1965.

Criss, who received a lengthy standing ovation when he fouled out of the game with one second left in the second overtime, also broke the Scranton team record for most points in a single game. Swish McKinney held the previous mark of 58 points in a single game, and Willie Somerset had the second highest output with 50.

At 5-foot-8, Criss doesn’t measure up to the 6-foot-9 and seven-foot giants he plays against. The former New Mexico State star’s head barely reaches the armpits of most EBA players, but he compensates for his size with speed, energy, confidence, and excellent shooting accuracy.

The teams played a total of 58 minutes, including the two five-minute overtimes, and Criss went the entire distance except for the final second when he fouled John Baum and disqualified himself with six personal fouls.

The foul call set off a game-ending controversy because referee John Thompson ruled that Criss committed the violation before a desperation baseline jumper by Baum, which zipped through the net and would have sent the contest into a third overtime.

Thompson ruled the violation was not a shooting foul, a decision which was heatedly argued by Hazleton coach Tony Manfredi and his players. Manfredi pointed out that the clock is supposed to stop on every whistle and every score in the last two minutes in pro ball, but no avail. When the rhetoric ended, the Bullets were given the ball out of bounds with one second on the clock, and the inbounds pass was intercepted by Scranton’s Bernie Harris to end the game.

The exciting finish was provided when the teams finished regulation play tied at 117 on a pair of free throws by Criss, who made 18 of 20 from the foul line, Criss tallied four of Scranton’s six points in the first overtime, which ended with the score deadlocked at 123.

The EBA scoring leader then accounted for eight of the Apollos’ 10 second-overtime points. He hit a baseline jumper to put Scranton ahead, 121-129, and after Roland “Tree” Grant made a field goal to again tie the score, Criss made a 20-foot shot with 45 seconds left.

Hazleton’s Baum missed a shot, and Grant also missed after claiming the rebound. Cyril Baptiste rebounded Grant’s missed shot and the Apollos ran down the clock. Criss missed a shot with five seconds left, and Hazleton called time out after grabbing the rebound. Criss then fouled out on the inbounds play.

Criss pumped in 60 points in the regulation, including 22 in the third quarter to equal his first half total. He padded his record total with 12 points in the overtimes . . .

Criss’ 22 points in the third quarter propelled Scranton to a 90-86 lead entering the fourth period. Scranton outscored the Bullets, 36-22, in the third and took the lead into the final minute after tying the count at 76 with 10 unanswered points . . .

The fourth quarter was a seesaw battle with the lead changing hands eight times and the score tied on six occasions. Hazleton led, 117-115, when Billy DeAngelis fouled out and converted both free throws to knot the score . . . Criss literally drove the Bullets crazy, particularly DeAngelis, who had the job of guarding the Scranton court general most of the night . . .

When Criss broke McKinney’s team scoring record, even his teammates on the bench were shaking their heads in disbelief. He was roundly congratulated by the Apollos’ players when he bowed out on personal fouls.