[Most NBA fans who can trace their hardwood obsession back to the 1970s recall the Vitalis One-on-One Competition during the 1971-72 and 1972-73 seasons. The competition aired at halftime of ABC’s NBA Game of the Week, pitting some of the league’s better shakers and bakers, knockdown shooters, and rim protectors in a single-elimination tournament.

A quick admission. The competition sounds a lot more exciting than it really was. In 1972, for example, Detroit’s burly 6-foot-11 Bob Lanier prevailed in the final over Boston’s 6-foot-3 speed merchant Jo Jo White. Lanier, exploiting his height advantage, backed down White in a dull thud of dribbles to about five feet from the basket, pivoted, and hoisted his soft, left-handed jumper. White was helpless on defense. Lanier was on a roll.

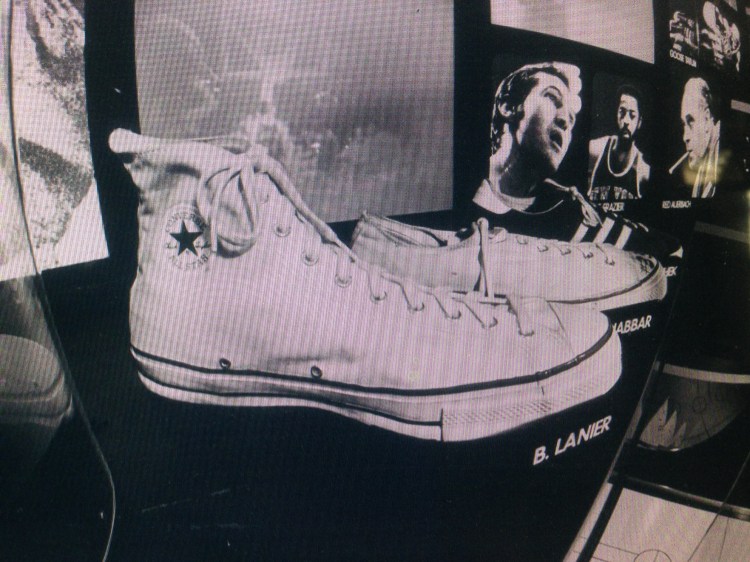

After the last five-foot gimme, Bill Russell (then the color analyst on ABC’s Game of the Week) cackled his way onto the court and handed Lanier a briefcase reportedly filled with 15,000 one-dollar bills. Big Bob looked into the ABC cameras, mugging with the briefcase and basking in his new, though still very debatable, title of the NBA’s King of One-on-One. (Lanier’s victory, after all, was a testament to NBA brawn, not the grace and skill that was then popularly associated with one-on-one play.)

In this article, published in Popular Sports’ 1973 Basketball yearbook, the prolific columnist Sandy Padwe (Philadelphia Inquirer and Newsday) latched onto Lanier to talk one-on-one basketball. He also oddly latched onto NBA coach Jack Ramsay to discuss the fine art of one-on-one play. I write “oddly” because Ramsay wasn’t a huge fan of one-on-one basketball. Ramsay, though he would run “an iso” when the situation dictated it, much preferred calling plays and keeping his players in motion.

Still, Padwe’s article offers a nice look back to the days when one-on-one play was still fresh on everyone’s minds, mysterious in many iterations, and viewed for the first time to be “the name of the game.” As one 1970s writer stated the case:

Basketball is a team sport, an exercise in precision movement by a well-drilled unit. And yet, reduced to its most elemental form, the game becomes man against man, speed against reaction, size versus agility, the parry and the thrust. It becomes, in short, one-on-one. Stripped of its outer refinements, basketball is no more than the basic concept of all games—one man pitted against another. Within the larger framework of team coordination and predetermined maneuvers, the game is a series of individual duels in which athletes test their brains, their quickness, their courage, and their experience against opponents of equal skills. The results of these perimeter engagements determine the course of the overall battle. From the city schoolyards to the collegiate field houses to the professional arenas, one-on-one is the name of the game. This is what it’s all about . . .]

****

Stop at any playground in any major city in this country. Summer, winter, autumn, or spring. Peer through chicken-wire playground fences at the metal baskets without nets. Then watch the kids, and the teenagers, and the men.

Most often the game will be five-on-five or three-on-three or two-on-two, but sometimes it will be that special kind of basketball, one-on-one. Two people matching skills, not for crowds, simply for satisfaction. Many of the moves will be beautiful, unexpected, graceful. It is a city ballet, different in many ways from similar games played at a remote playground or backyard, say, in the Plains states or the greater Northwest.

Not that this in any way downgrades the type of basketball played there, but one-on-one as an art form flourishes in the cities among city ballplayers. It is more than a game. Sociologists would have a tremendous project describing it in all its nuances.

One-on-one players often are the bane of basketball coaches who are unprepared to incorporate the skills of the gifted street and playground player into a team game. But it can be done, and it is being done all over the country by the more flexible and more imaginative coaches.

“You need a couple of good one-on-one players on any team, if that team really is going to be exceptional,” said Bob Lanier, the 6-foot-11 center for the Detroit Pistons. Lanier should qualify as an expert. Not because he is a professional and not because he was an All-American at St. Bonaventure. Bob Lanier is the National Basketball Association’s one-on-one champion. He won the title, defeating guard Mike Riordan of the Baltimore Bullets last winter [Note: Lanier beat Riordan in the third round of the competition, not the finals]. The win was worth $15,000 to Lanier.

“When I was a kid growing up in Buffalo, I played a lot of one-on-one at Delaware Park,” Lanier said. “Now, during the offseason, I don’t play it very much at all because I don’t want to take a chance on hurting my knee again.

“But it’s a great way for any player to work on his weaknesses and improve them. And to me, one-on-one has always been as important in developing the mental aspect of my game as the physical one of moves and shots and things like that.

“What I mean by mental in one-on-one is that when you play it right, it teaches you to think of ways to get your man off-balance and unprepared, and that’s as important as good shooting.

“I’m talking about setting a man up. What do you do, say, when he might be expecting a jump shot? You try to outthink him and set him up for a hook or what might be a better shot. It’s a constant mental battle with the other guy. He’s trying to anticipate, and you’re trying to outthink and surprise him. One-on-one gives you a lot of practice in that part of the game.

“On the Pistons, we have a variation of one-on-one that we play a lot. Usually, we do it before or after practice. You can have five guys playing. It’s like one-on-one, except that the guy who scores the basket stays out on the floor and takes on the next guy. That way, if you’re staying out, you’re constantly facing a different type of player with different moves and ideas. It’s great for getting up a sweat and polishing parts of your game.

“You’d be surprised who wins. It isn’t necessarily the biggest man or anything like that. It’s the guy with the best all-around game. That’s the same way in a regular game. I know that a lot of coaches look down on one-on-one. Sometimes, they’re justified because there are guys who overdo it a lot. There are all types of players in basketball. Selfish, unselfish, team, individual.

“Me, I love to watch the unselfish guy who can move with the ball in one-on-one situations and who can set up the rest of the guys on his team. You get a lot of guards like that; but big guys have to be able to do it, too.”

Lanier’s personal preferences for the best one-on-one players in the National Basketball Association include Dave Bing, his teammate at Detroit; Nate Archibald of the Royals; Archie Clark of Baltimore; Jerry West of Los Angeles; Norm Van Lier of Chicago; Lenny Wilkens of Seattle; and Walt Frazier of New York.

“Most of those guys,” Lanier said, “are small and fast and, as far as I’m concerned, play one-on-one the way it should be played in a game. They’ll take the ball in and penetrate to the point where they can set up another player.”

Not every player in the NBA participated in the one-on-one tournament, which was played during halftime of national telecasts last winter. Among the missing were Wilt Chamberlain and Abdul-Jabbar, the big men who have dominated the game. “No,” Lanier said, laughing, “I’ve never played a straight one-on-one with either Wilt or Kareem. So, I don’t know how I’d make out. To me, Wilt plays good defense, but I don’t think he handles the ball that well. Kareem handles the ball well, and he’s more of a problem because he shoots a pretty good outside shot.

“I think part of the reason I won that thing against Riordan was because I handled the ball pretty well. The better a big man handles the ball, the more he’s going to be able to do for a team. Riordan was very tough, though, and so was Jo Jo White (Celtics). He came back and was catching me. In a one-on-one game with little guys like Riordan and White, if they’re having a good day with an accurate jumper, it’s going to be tough.

“But the whole thing about one-on-one is what it does for you overall. A basketball player has to be an individual at certain times during a game. There always will be a moment when it’s you against your man.”

As a coach, Jack Ramsay has had to deal with both the positive and negative aspects of one-on-one play. Ramsay, one of the nation’s outstanding collegiate coaches at St. Joseph’s (Pa.), moved from there to the Philadelphia 76ers and this year has switched to the Buffalo Braves.

“The value of having a good one-on-one player,” Ramsay said, “is that as part of good team play there will come a time for an individual to beat his man. You have to have players with the skill to do that. What I’m saying is that the one-on-one maneuver will come during the offensive flow at a particular moment when it’s needed.

“Of course, the danger is well known. There are players who might do the one-on-one stuff too often or it might be the primary part of their offense.

“But in the NBA and all of professional basketball, almost everybody has a skill where he can beat his man in some particular way that he has developed through the years. For a big man, it might be a certain turn or move into the basket or a certain shot. Just some special thing he has perfected.

“Or, you might have a forward who has worked on driving a certain way. Or a guard with a distinct move or jump shot. But the defenses in the NBA have become so attuned to the individual characteristics of the players that it no longer becomes a task of beating one man for the guy on offense . . . But it’s something you have to get done in the course of a game and, like I said, everybody has the ability to beat his man some way.”

Like Lanier, Ramsay also has his list of players who maneuver best in one-on-one situations. “Walt Frazier is exceptional,” Ramsay said. “So is Billy Cunningham on that drive he has from the side. Jabbar can beat you a lot of ways, but he seems to like that hook shot. Then there is Oscar Robertson, Nate Archibald, Dave Bing. Jerry West hardly goes one-on-one anymore, but he used to be tremendous at it.”

“Earl Monroe is a great one-on-one player, but sometimes he gets in situations where he isn’t helping. I’m not saying he’s selfish, but he’s an example of a guy with the tremendous one-on-one talent who has had some problems.

“To me, a great example of one-on-one play was during the playoffs (Los Angeles vs. New York for the NBA title) when Jim McMillian was going against Bill Bradley. McMillian did a great job on Bradley, and Bradley is an awfully good player. But McMillian only used his one-on-one moves during the flow of team play to get his kind of shot, and that helped the Lakers.”

How, Ramsay was asked, does the sensitive coach allow the gifted player with extraordinary one-on-one skills to maintain the individuality he has built up through so many hours on a playground?

“First, you impress on everyone that the purpose is to win. All good players recognize this. I find most players feel that way. You don’t win with one-on-one alone. Most players accept that fact and know that one-on-one is used to take advantage of particular situations,” Ramsay said.

“My teams worked on it mostly during the preseason period. We needed the skills that one-on-one helps you develop. But during the season, one-on-one play usually came before or after practice.”

It is a debate which seldom stops in basketball—the freelance vs. the team game. There often is beauty and artistry in both aspects. And both offer basketball in its purest form.