[No need for an intro on this one, except to say, the article ran in The Complete Handbook of Pro Basketball, 1984. The byline belongs to Stan Hochman, then an award-winning columnist with the Philadelphia Daily News.]

****

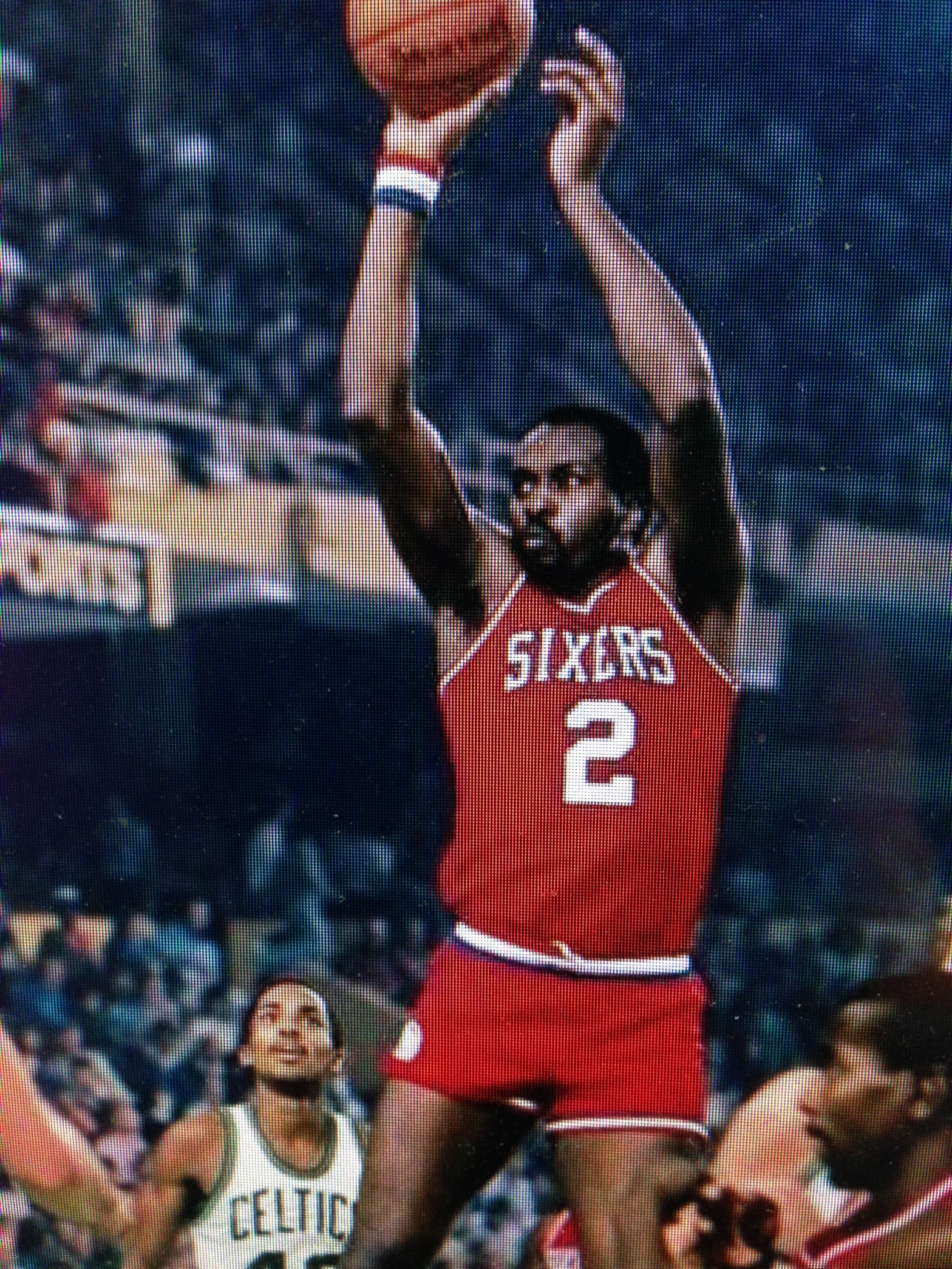

For seven years, Julius Erving, the legendary Dr. J, had been carrying an ugly monkey on his back. Actually, it had been more like a snarling gorilla than a monkey. The first six years of Erving’s NBA career, the Philadelphia 76ers had soared through the regular season, only to have crashed in the playoffs.

Three times they had reached the championship finals, only to have come away with their knuckles scraped rather than adorned. The first time, they had blown a 2-0 lead to Portland and, afterward, an advertising agency had come up with the “we owe you one” slogan that would haunt the Sixers for years.

Now, all that was history. The Sixers had won the NBA title, blitzing Los Angeles in the finals, and Erving stood behind a thicket of microphones in the bedlam of Veterans Stadium, parade confetti in his hair, cheering in his ears, the championship trophy at his side.

“We have the world championship,” Erving told the crowd of 50,000, “because after six years of knocking at the door, even though we felt good in our hearts, in our minds, in our souls, we went out and got, for cold cash, a hard hat. And we got the final piece of the puzzle that made us complete in every sense of the word. And there was nothing pretty about what we did to the NBA this year . . . it was beautiful.”

Moses Malone was the hard hat—6-foot-11, 255 pounds of steel-driving man. He showed up in overalls every night. And when everybody else was wobbly with fatigue, he was the guy still pounding rivets, drenched in sweat, a fierce scowl on his face.

Erving was right. What the Sixers did to the NBA wasn’t pretty. Tough defense—a lot of guys blotting out passing lanes, doubling up on people, clawing at them—never is.

And there was Malone, the hard hat in the middle, sweaty and slope-shouldered, dominating the fourth quarter, grabbing rebounds from guys who jump higher, who have bigger hands.

The missing piece of the puzzle cost Sixers’ owner Harold Katz a first-round 1983 draft choice they had obtained from Cleveland and Caldwell Jones, a forward as thin and as tough as barbed wire.

Katz signed Malone to a six-year contract worth $13.2 million in cold cash. Malone was worth every dime. Attendance increased, despite a 45 percent boost in ticket prices. The Sixers started 50-7, finished 65-17, and then scorched through the playoffs with a record 12-1 run.

Malone, for the third time in his NBA career, was named the most valuable player in the league. He led the Sixers in scoring with 24.5 points per game, and led the NBA in rebounding, with an average of 15.3.

Through it all, Malone hoarded his privacy, answering only those questions that dealt with basketball, turning away all requests for in-depth interviews.” Moses has no ego,” said his wife, Alfreda. “That’s what attracted me to him. He’s a private person, down-to-earth, the strong, silent type.”

He grew up that way—strong and silent—in Petersburg, Virginia, in a hard-scrabble area called “The Heights.” His father left home when Moses was two. His mother, Mary Malone, worked days as a packer in a supermarket and nights as a nurse’s aide.

“I’ve seen a lot of poverty, traveling through Alabama and Mississippi, but Moses’ situation was the worst,” said Smokey Gaines, the San Diego State coach who recruited Malone as a high school senior.

Gaines was not alone. One college assistant coach lived in a Petersburg motel for 61 days, pursuing Malone as he led Petersburg High to 50 consecutive triumphs and two state championships. “I visited 24 colleges,” Malone recalled years later. “After that, they changed the rules.”

Malone apparently settled on Maryland, signing a letter of intent with a jubilant Lefty Driesell. But Moses had made a promise to himself—he was going to be the first player to go straight from high school to pro ball. He put it down on paper and stuck the note inside his mother’s Bible.

Mary Malone wanted her only child to attend college, but the pro scouts told her to take a good, long look inside her almost barren refrigerator. And then, one night, representatives of the ABA’s Utah Stars came in and spread $100 bills across her kitchen table.

A few days later, Moses Eugene Malone signed a seven-year, $3 million contract with the Stars. It was the first step in a cruel ABA caravan. Malone, an unsophisticated, 18-year-old Black kid, arrived in predominantly white Salt Lake City. A cynical disc jockey nicknamed him “Mumbles,” and Malone retreated deeper into his shell.

“I remember the first game he played in the ABA,” said Bill Melchionni, one of four players to win championship rings in the ABA and NBA. “He was a young, skinny kid. They told him to go stand under the basket. The only way he was gonna get the ball was on their missed shots.

“He could hardly dribble the ball, but he just kept working those boards. I don’t think he took a shot that was more than three feet that night.”

The Stars shuffled coaches at midseason. Malone responded to the gentle coaxing of Tom Nissalke and went on to become the ABA Rookie of the Year. The next season, Malone broke his foot. The Utah franchise shattered, too.

St. Louis got him in a lottery. And then, the ABA closed shop. Portland picked him in the dispersal draft, but only as trade bait, because the Trail Blazers still had a young, talented, aware center in Bill Walton.

When Portland coach Jack Ramsay told his team that Malone has been traded to Buffalo, Walton asked, “What did you get for him?”

“We got a first-round pick,” Ramsay said.

“You didn’t trade him away,” Walton grumbled. “You gave him away.”

A week later, after using Malone for only six minutes, Buffalo swapped him to Houston. John Y. Brown, part-owner of the Braves, insists he was out of the country at the time the deal was made. Malone went to Houston for cash and two first-round picks. In Houston, he was reunited with Nissalke and the chemistry clicked.

“If he had the hands,” Nissalke bragged, “he might be the greatest player of all time. He’d be a 6-foot-11 Dr. J.”

In Houston, Malone’s scoring climbed every year, going from 13.2 points per game to 31.1. He led the league in rebounding three times. He lugged a slow, methodical team to the NBA finals against Boston. “I could get four guys from Petersburg and beat those guys,” Malone boasted, trying to inspire confidence in his teammates, who may have been awed by the Celtic mystique.

The next year, he averaged 31.1 points per game, pulled down 1,188 rebounds, and led the league in minutes played. He scored 53 in one game, took down 32 rebounds in another. Nobody matched those numbers. Malone won his second MVP bauble in a landslide.

And through it all, he was the ultimate hard hat. He never grumbled, never missed a practice, a plane, or a game. He never loafed, always relentlessly pursuing rebounds. “There’s only one ball,” he’d say, “and I want it.”

His contract ran out in Houston. The owners hinted they would sign him to a huge new one. He told the builders to go ahead with construction on his new home in Houston. Meanwhile, Katz had swapped the popular, but perplexing, Darryl Dawkins to the Nets. He needed a big man in the middle, the missing piece in the puzzle that would take his team to a championship.

Katz signed Malone to a controversial offer sheet that contained so many complex incentive clauses, Houston couldn’t possibly match. An arbitrator ruled that the sheet violated the spirit of the NBA’s “right of first refusal” arrangement.

So the Sixers worked out a deal, sending Caldwell Jones and the first-round pick they had obtained from lowly Cleveland to Houston. “If Cleveland finishes last [it didn’t],” Katz explained, “it still only has a 50-50 chance [that] you win the coin toss so you can pick Ralph Sampson.

“I’m not like George Steinbrenner. I’m not doing anything crazily. We got rid of the salaries of Jones and Dawkins. We got $700,000 in cash from the Nets. The deal is going to be almost a complete wash. Plus, we got the best player on the team.”

When Malone arrived in Philadelphia to meet the media, he wore jeans and a plain brown shirt. workmen’s clothes. He spoke softly, with an earthy, workman’s vocabulary. Pressed to explain his rebounding prowess, Malone shrugged those rounded shoulders and said, “I just go to the rack.”

The writers knew he would face a harsh crowd because of his huge price tag. Would that burden wear him down, physically and mentally? “I never thought about it,” he said. “But then, I never thought I’d be a pro ballplayer. The Lord looked down on me and said, ‘Well, Moses, I think you should be a ballplayer.”

Dawkins had been a crowd favorite for his Lovetron fantasizing, his poetry, his backboard-busting, his occasional moments of brilliance. Malone was not concerned about comparisons. “Darryl,” he said, “is a great player. He’s got a lot of talent. We’re both in the same class. I just work harder than Darryl.”

Malone works harder than anyone, harder than everyone. No one in Philadelphia fully appreciated it at the time. Everyone knew Malone could rebound, but there were other questions about him, because Houston had walked the ball upcourt.

Could Malone keep pace with a fastbreaking team? Could he pass the ball with those undersized hands? Could he block shots, giving the guys out front a chance to play pestering, gambling defense? And could he coexist with Erving, the acknowledged superstar?

“It’s Doc’s show, and I just want to watch the show,” said Malone. “In the ABA, Doc was always a great show. Now, I’ve got a chance to play with Doc, and I think it’s gonna be a better show.”

He would do more than watch, of course. Much, much more. Having said the right things that first night, Malone did all the right things night after night after night. The Sixers moved from 20th in the league in rebounding (3,420) to first (3,930).

They raced to a 50-7 start, the gaudiest beginning in the history of the league. Before the season had opened, Malone had sauntered past Katz and promised 70 victories. The bold prophecy barely missed. Racked with late-season illnesses and injuries, the Sixers settled for a 65-17 mark. Malone missed the final four games of the season with a gimpy knee, tendonitis he had ignored for weeks.

In the lull that followed the end of the regular season, Coach Billy Cunningham asked Malone how he felt about the upcoming playoffs, and Malone said, “Four, four, four,” predicting a sweep of each series. People stopped chuckling after the Sixers swept the swarming Knicks in four straight.

New York had a tag-team approach to Malone, using the pair of Bill Cartwright and Marvin Webster against him. Malone outscored the tandem, 125-60, and outrebounded them, 62-36. In the third game, he dribbled through four Knicks for a layup. In the fourth quarter of the fourth game, he got seven of Philadelphia’s 17 rebounds and 13 of Philly’s 28 points. The fourth quarter would belong to Malone throughout the playoffs.

“You’ve gotta have desire,” Malone said, trying to explain his stamina. “The last quarter, you just put a little more effort to be strong, to play hard. It’s time to go to work.”

The Sixers had gotten him for his rebounding, and now he was unfurling other skills. “I try not to play the same game every night,” he said. “If people are surprised, I’m not surprised. I had the jump shot in high school.

“I went to Houston, and they tried to label me. They said I could only rebound. I did other things, but the media didn’t notice. I suppose when I came here, they didn’t believe me.”

Milwaukee was next and, after scorching to a 3-0 lead, the Sixers went sprawling in the fourth game. But they thumped the Bucks in the next game, with Moses doing his King Kong imitation in the fourth quarter. “He’s ‘The Man,’” said Milwaukee coach Don Nelson. “His players know it. We know it. Everybody knows it, but nobody can do anything about it.”

“He’s the greatest player in the game,” said Bob Lanier, who had his hopes for his first championship ring crushed. Lanier, Alton Lister, and Harvey Catchings had bumped and thumped Malone throughout the five games, but nothing could derail Moses’ locomotive approach.

The Lakers were next, battered and weary from a six-game struggle with San Antonio. They tried to conserve Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s energies by using Kurt Rambis on Malone. Malone loved every mismatched minute of it. “Ain’t no 6-foot-8 guy gonna check me,” Malone muttered. “He can’t guard me. They keep sticking that little guy on me like that, I might have a field day.”

The Lakers had lost rookie sensation James Worthy to a midseason injury. Bob McAdoo was hobbling with a leg injury. Norm Nixon played despite the pain of a shoulder injury suffered in an opening-game collision with Andrew Toney, but was ineffective.

The Lakers owned the lead at halftime of every game. And in the fourth game, they led by 16 at one point. But Malone led the way to crunching comebacks every time.

“Malone gives them exactly what they were looking for,” Lakers’ coach Pat Riley said. “When their outside shooting fails, he’s there in the middle to take over. He’s not only an offensive player, he’s a defensive player. He’s the missing link they’ve been looking for.”

Trailing by 11 at the start of the fourth quarter, the Sixers churned away. Late in the game, Erving reached back into that magic bag of skills for seven consecutive points. With four minutes left, Alfreda Malone, watching the telecast with other wives at the Ervings’ Villanova home, said, “We’re gonna win.”

“I said it because I know Moses,” Mrs. Malone explained. “I could see them pulling together. And when Moses is determined, a team of wild horses couldn’t keep him from doing what he wants to do.”

So the Sixers made history, stomping through the playoffs in 13 games, sweeping the defending champions in four straight, missing Malone’s bold forecast by one game, chasing the monkey off Erving’s back.

They came home to a tumultuous celebration, a parade watched by an estimated 1.7 million, followed by victory laps in convertibles around the baseball stadium. Cunningham, giddy with euphoria, held the glittering trophy aloft in the brittle sunshine. The 50,000 fans at Vet Stadium chanted and shouted.

“And Moses says,” Cunningham yelped, “that we will repeat. Re-peat. Re-peat.”

The crowd hushed. If they had learned nothing else in the awesome season, it was that, when Moses Malone speaks, everyone ought to listen.