[Over the years, gigabytes of data have been filmed, jotted down, and published about the enigmatic Bill Russell. Where do you even begin to dive into Russell’s legend and historic body of NBA work, especially to mark his passing at age 88 and to celebrate a life well lived? I’ll leave it to others to begin waxing nostalgic about his legacy as the game’s first great defensive center, his rivalry for the ages with Wilt Chamberlain, his unique bond with Red Auerbach, and his unprecedented total of 11 NBA titles. But there’s one achievement in particular that I’d like to focus on, which might inadvertently get shuffled to the bottom of the deck and mentioned just in passing. It’s one of Russell’s most-enduring accomplishments: breaking the coaching color line in modern American professional sports.

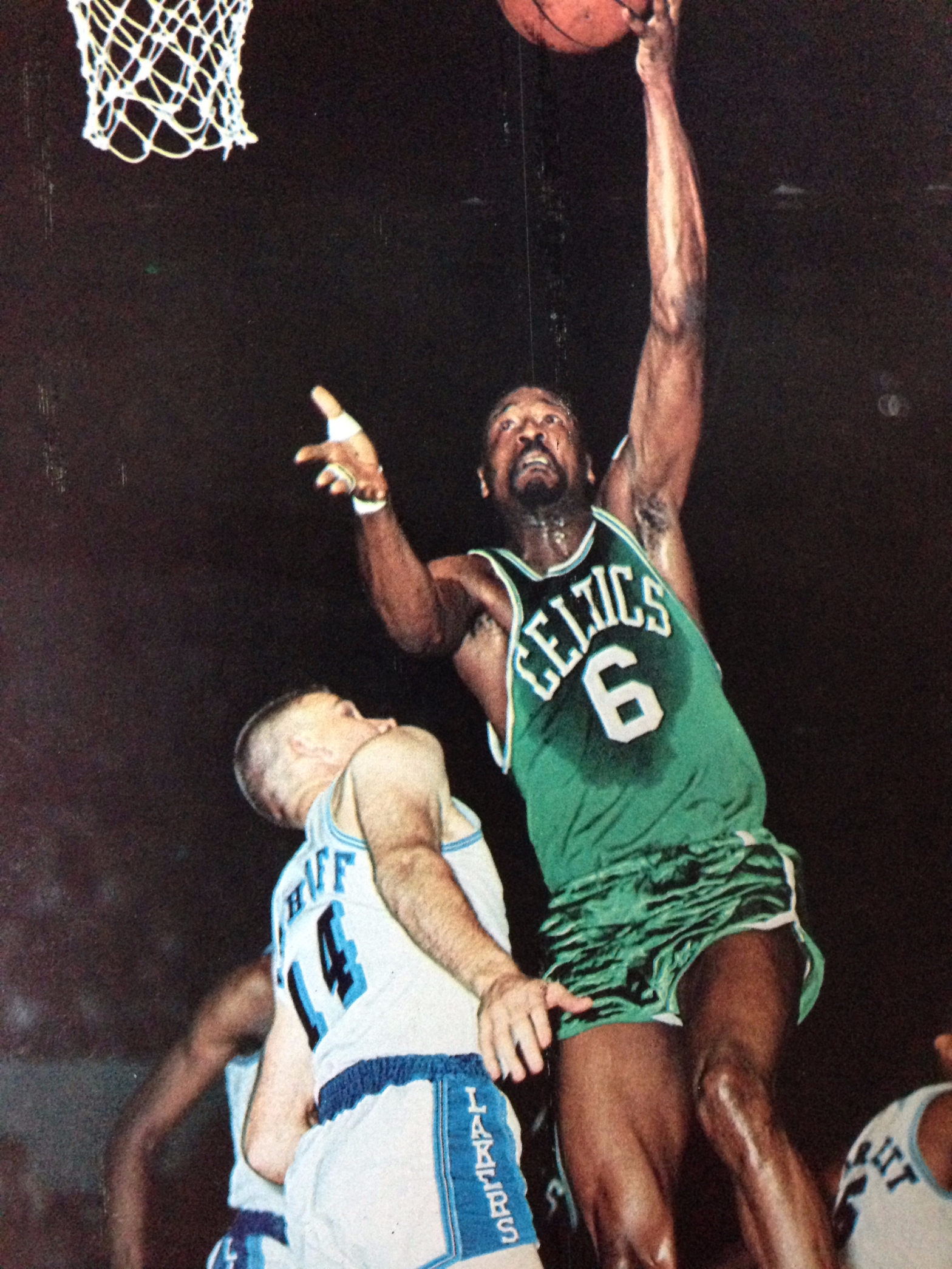

Russell crossed that treacherous line in the fall of 1966, probably with his trademark loud cackle, and this article about the Celtic great’s “biggest challenge” summarizes well the stakes and mood in the country at that very time. The byline reads Bob Stewart, whom I know absolutely nothing about, and his piece ran in Complete Sport’s Pro Basketball Illustrated 1966-67 magazine. Here’s to number 6 in Celtic green.]

****

“I can’t really explain why I took the coaching job, except that at least I’ll be playing for someone I can get along with.”

It was said with a smile. A smile perhaps genuine, perhaps sardonic, perhaps in good humor, perhaps not.

It was said by Bill Russell, and like so many things Russell has said since he became coach as well as player for the Boston Celtics, the remark has been discussed and dissected by the thoughtful and the thoughtless fans who live and die with the ebb and flow of power and lure of professional basketball.

It is strange and somewhat disturbing that sport, which broke the color line long before the first faint dawnings of the civil rights movement, should now find itself whispering and indeed worrying about the effect Bill Russell will have upon the structure of American sport.

Russell is, of course, the first Black person to take command of a major sport enterprise. In an ideal world, this historic first would occasion only delight that such a man, on his merit, has been singled out for a reward due to him. But live we do not in an ideal world, so that the path Bill Russell and his Celtics and the National Basketball Association must trod this season will be a path booby-trapped and mined with sinister dangers.

The success or failure achieved by Russell, his team, and the NBA in picking their precarious way along that path will, justifiably or not, affect the future ambitions and lifetime careers of Black athletes in baseball, football—indeed, in all sports.

When Branch Rickey, motivated by sound business or by righteousness—there are still those who dispute the man’s moving force—decided to shatter baseball’s unconscionable bar against Blacks, he moved with exquisite, calculating care. His selection of the then firmly disciplined, inordinately capable Jackie Robinson was a stroke of genius.

Robinson walked the fine highwire of his debut year, and those immediately following, with the skill, devotion, and technique his role demanded. Robinson had to be more than the superb baseball player he was. He had to be in every facet the symbol, the embodiment of the truth that sport can acknowledge no barrier based upon race.

It cannot be denied that Robinson paved the way for the others of his race. It cannot be denied that had Rickey selected for his pioneer some of those who followed the trail Jackie blazed, irreparable harm might have been done to the demolition of the color line.

There were small-minded opportunists who attempted to “cash-in on color” after Robinson had won his spurs. To their disgrace, they hauled up for exploitation, Black athletes who were not capable of playing big league ball.

In time, Robinson and the others who belonged on the field reached that total acceptance any fine athlete deserves. And in time, too, there was an opportunity for the white American fan to pay his belated respects to at least one of the great Black stars of the game who had been denied his deserved accolade because of his color—Satchel Paige.

There was no need of a Jackie Robinson in professional basketball. The game of run-and-shoot lacked the historic formalities of baseball. There was no color line to break when pro basketball skyrocketed off the church gym floors to capture the fancy of the American public. In no other sport is the percentage of Black players to white so high.

But basketball on the highest level has been run by the whites, and now, in the selection of the first Black to be accepted on that level, the Celtics have chosen a man steeped in controversy. Is the move a sound one?

Remarkable to consider is that the selection of Russell cannot be regarded as a cheap grandstand play to build attendance by exhibiting a curiosity. Were one of the weaker teams of the league to name a Black coach, the move would be undoubtedly suspect. But the Celtics are the symbol of NBA greatness, boasting a record all but unchallenged in professional sport.

The cigar-chewing, sometimes-vitriolic, always-impassioned Red Auerbach had instilled in the machine he built in Boston a fierce pride, consummate skill, and incredible teamwork. There were Cousys and Heinsohns and Havliceks and Joneses and Russells, but also there was always Auerbach and the Celtic spirit.

When the Celtics were involved in tight, bitter struggles, Auerbach became the sixth man on the court for Boston. He would rage, fume, and bluster—and, often as not, be ordered out of the arena. His team—and maybe more important, the fans—tolerated and even enjoyed his pyrotechnics.

But what will be the reaction, if Coach Bill Russell attempts the same wild-eyed embattled approach to the white officials on the floor? And what will be the latent anti-Black sentiments of a portion of the crowd when this superb Black man charges an official of their own race? Will they take the same attitude that they took to Russell the player? Will they accept him as the new Auerbach?

Yet the problems go far beyond such possible incidents. Russell, a militant man, always has been team man in his relations with his mates. In basketball, in the fleeting seconds of the 24-second clock, men attack and defend with a fluidity and speed unique to their game. Russell’s ability to adapt to that ferocity has been magnificent. He has been an integral part of the finely honed Celtic squad that has dominated the NBA. But now the question has been posed: Can he remain a part of that machine, and at the same time dictate how that machine will operate?

The fortunes of player-coaches in any sport have been far from universally happy. The man rising from the ranks in sport or in business has had too often to learn the bitter lesson that the role of “boss” creates a gulf between him and the men who once worked by his side.

With his fellow veterans of the Celtic wars, Russell will probably have little trouble. Battle-hardened, particularly by the determination and pride that carried them to the crown again last season, those veterans know their man, their Russell. But there are those who carried only spears for Auerbach, there are also those who come into the arena for the first time this coming season. It is over these people that Russell must establish his right to succession. It Is here that the personality of the man and his beliefs must and will be tested to the utmost.

There is no “Uncle Tom” to Russell. His views on civil rights are explicit in his autobiography, and in his speeches. Russell does not pose as a militant—and rightly so, for there is no pose about the blunt approach he has to the problem of race. That there is a problem he knows well, admits, and has lived with—and against.

It is candor that Russell calls it, this bitter, yet undisguised manner in which he meets the racial issue. It may be candor, indeed undoubtedly is by Russell’s lights, yet it is aggressiveness to the point of baiting in the lights of others.

The status quo is not for Russell. Why should it be? But in his role, this breathtaking new role in the higher echelons of sport, he is going to find that there will be many who will retreat only grudgingly from the crumbling status quo of racism.

The delusion—if it can be called that—will have been possible because Russell and others found in sport, and in basketball in particular, a willingness of men to work together for the common good of each other and of the team for which they toiled. In his book Go Up for Glory, he makes what seems almost wistful notice of what it is, or was, that made his Celtics so great.

“There were Jews, Catholics, Protestants, agnostics, white men, Black men. The one thing we had in common was an Irish name. The Celtics.”

As coach of those very Celtics, Russell will have to raise his sights, broaden his outlook on pro basketball far beyond the confines of whether his Celtics win or lose. Like it or not, Russell has been protected by his status as a player throughout his remarkable NBA career. He can and does write with great flippancy and pontification about the officials in the pro games. But he will surely find that when now he challenges them, or cajoles them, or jokes with them, they are going to be quiveringly alert to his new status—that of coach. Where more than once he himself pulled Auerbach away from futile court battles, who now will take his part, striving for the cooler heads to rule?

It seems that Russell expects—will demand—immediate acceptance as coach. That acceptance, however, has to be earned, just as it has had to be earned by the numerous white coaches of other teams who proved failures. If Russell fails, he shall be doing himself and his cause terrible harm, should he blame that failure on the color of his skin.

For fail he can, fail in the countless ways Auerbach did not fail. He can fail in strategy. In the handling of men. In sensing precisely when to bench this many, play that one. These are the normal crises a coach must face. They can become abnormal if that coach happens to be of a different race, as is Russell, or of difficult temperament, as Russell proudly admits he is.

The Black athlete has come a long and most deserved way since the days when Jackie Robinson had to take abuse in silence. Today, in baseball and in basketball and football, ability and only ability is the criterion of acceptance.

Surely, it is time that Blacks take their rightful place in the hierarchy of the sports they play so splendidly, and to which they have given such an added lustre and lucre. Indeed, it is far beyond time that Black Americans be given the right to command from the benches of teams in all sport and to sit on the boards of all clubs.

The Celtics have stressed that in Russell the man, the tactician, the organizer, they place their trust and confidence as coach. They had divorced themselves from all consideration that he is also a Black man, and they have expressed their faith in the American basketball fan in insisting that they will so regard Russell.

It is a mighty challenge, to Russell and to the fans. If the challenge is not met, Russell will find that the trail Robinson blazed is not his, but that he has found yet another part of the forest—or of the jungle.

The first Black man in so delicate a post needs all his skill, all his humanity, to succeed. And he needs even more the support and understanding of all those, of any race, who profess to believe in sport.