[For Wilt Chamberlain, life was always lonely at the top of the basketball world, a point that Jerry West articulated well several years later. “The ironic thing about Wilt was that he never seemed to be relaxed and fun,” West told author Roland Lazenby. “I think after he got out of basketball, he became much more relaxed, much more fun. Much of it had to do with the fact he was Wilt Chamberlain, and no one pulled for him . . . There’s no question it was tough to be a giant.”

The great journalist Frank Deford seconded West’s assessment in his 2011 autobiography Over Time, “. . . Deford wrote, “I’m not so sure that there’s ever been a great star athlete, besides Wilt, who was so uncomfortable when playing and then so much happier retired.”

One possible exception might be Lew Alcindor, a.k.a., Kareem Abdu-Jabbar, whom Deford interviewed as a young collegian and remembered in his memoir as a total disaster. “[Alcindor] had been schooled to be wary of reporters, and it was immediately apparent that he was suspicious of me—if, indeed, he plain didn’t like me,” Deford remembered. “It was a painful evening.”

No doubt helping to school Alcindor, the college kid, was his mentor Chamberlain. He had taken a shine to his gangly, 7-foot-3 heir apparent and often advised him on just how lonely it was at the top. It was a personal narrative that the two shared.

But, as this article lays out, their special bond started to burst a few years later as Abdul-Jabbar prepared to enter pro basketball. The kid disrespected his mentor, and Chamberlain wouldn’t let go of the grumbling feud that soon stirred. Neither would Abdul-Jabbar, who took issue with Chamberlain loudly in print several years later. Abdul-Jabbar’s slight drew this tart response in Chamberlain’s 1991 autobiography, A View From Above, “What I will say is that it must be noted that [Abdul-Jabbar] has always felt that I am the only one who stands in the way of his being considered the premier center of all time. I say that because when I played against him, he always made a much greater effort to shoot many more times than he did against any center.”

Then Wilt grumbled from his proud view from above, “I guess I’ll also add that his shooting percentage was much lower against me (and, to be fair, against Nate Thurmond,).” He then mocked Abdul-Jabbar as a phony, and then tried to get back to the high road.

What exactly happened? Garth Williams, likely a nom-de-plume, tried to explain in the April 1973 issue of the magazine Sports Today. The article works more as an essay to jot down his first-hand observations and those of others. He might be right; he might be wrong. But it’s fascinating after the fact to remember that Wilt and Kareem plain just didn’t like each other.]

People tell me, what’s the big deal? Wasn’t it inevitable? People are just built that way, and just because one is 7-foot-1 and the other is 7-foort-3, that doesn’t mean they’re going to continue to like each other. If anything, it’s going to be the other way around. They’re going to grow to hate each other, and each time they meet it will be like a war because once Wilt Chamberlain stood there all alone on Mount Olympus, and he didn’t like it at all when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar took over his turf and turned into Mount Alcindor.

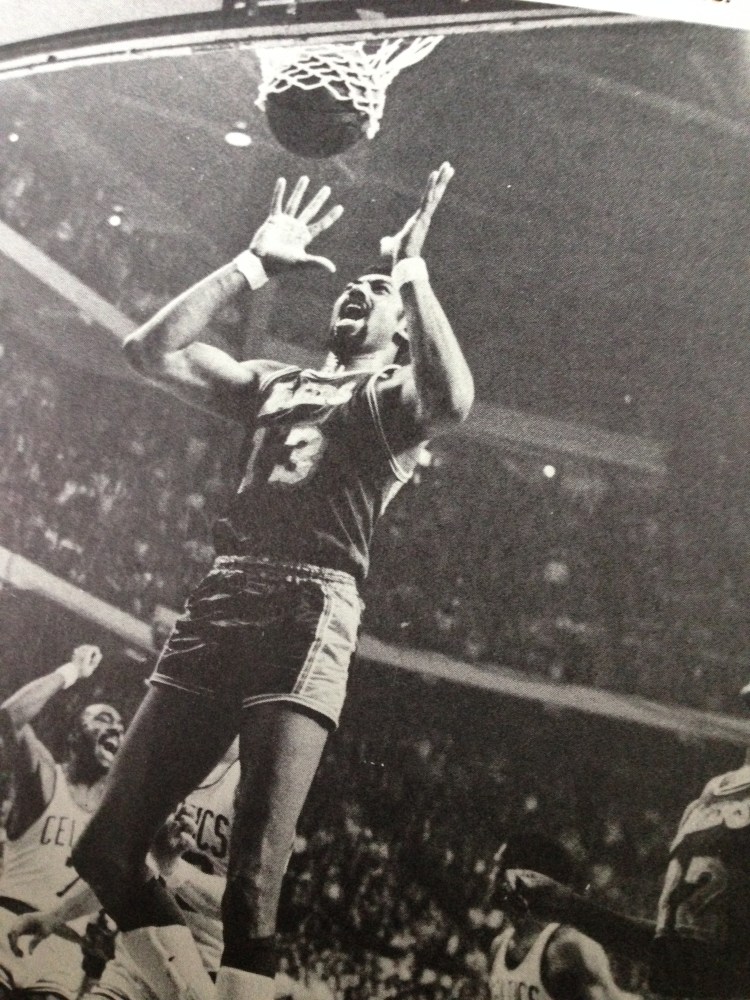

The Lion in the Winter may not be as fierce. But he is just as proud, and what Chamberlain has going for him is that his Lakers dethroned Kareem’s Bucks as NBA champions.

We saw it happen, of course, when Bill Russell was pro basketball’s big man, and then Wilt came along, and their rivalry developed. Chamberlain became the No. 1 individual, but it was the Boston Celtics who won the championships. Wilt seem to always to be left mumbling into his beard, while Russell wasn’t above reminding everybody that a team with Wilt just couldn’t win the big ones.

It infuriated Chamberlain, as well it should have. He might not have wanted to expose how much he disliked Russell. But it soon got about, and Wilt couldn’t very well hide it. He didn’t deny it: he just wouldn’t discuss it, and who is there with courage enough to go up to the big guy and ask: “Why don’t you like Bill Russell—are you envious of him?”

More recently, Chamberlain has refused to be interviewed nationally televised NBA games on ABC. He used to answer questions when Jack Twyman or Bob Cousy were the network commentators. But once Russell took over the job, there was no point in even trying to get Wilt to stand beside Russell, look sweetly into the camera and talk about cabbages, kings, ships, shoes, sealing wax, or basketball. Forget it. That’s how it stands.

Chamberlain and Russell are like oil and water, which leads us back to Wilt and Kareem, who hasn’t been around long enough—or so it seems—to have had ample time to have irritated Chamberlain’s sensibilities.

It may seem as though he’s been here forever, but Abdul-Jabbar is only in his fourth season in the NBA. Maybe it’s having been known by two names that makes it seem that much longer. Whatever, Chamberlain and Abdul-Jabbar have begun to react on each other as if both had skins made of sandpaper or one is allergic to the other.

Oh, Wilt pretends that there’s nothing there except a natural rivalry between two men to dominate their teams and perhaps the resentment (or jealousy or annoyance) of a man who is 36 against one who is 25 and has passed him both in individual brilliance as well as salary. Age hates youth only because it no longer has it. Youth has a certain patronizing quality to age, not kind, not even pretending to be kind, just a kind of insolence that says: “Get out of the way, Old Man. Your time’s up. You’re yesterday; I’m today.”

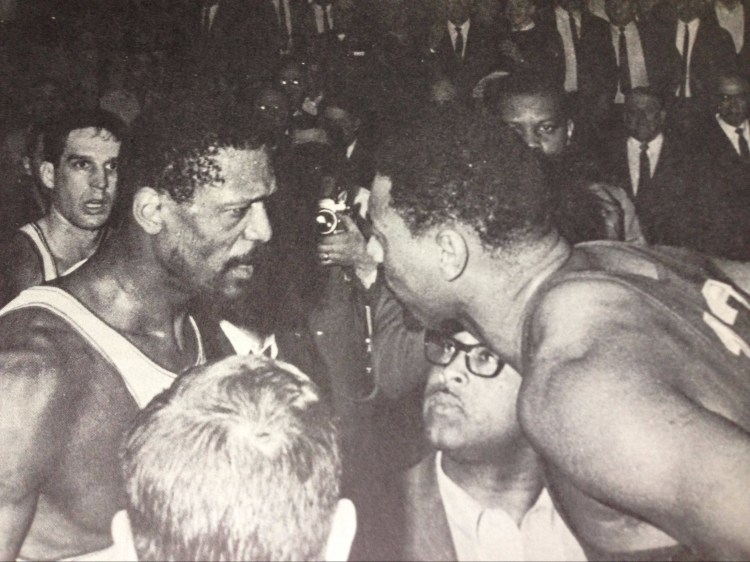

Well, the next time they play just watch the two of them as closely as possible. Not only when they’re combating each other physically under the boards, but in something so normal and natural as shaking hands at the center before the ball is thrown up for the jump. Or passing comments from one to the other during natural lulls in the game.

They just don’t shake hands or, if they do, it is just the slightest touch of skin. They say nothing to each other, although so often they are close enough to be whispering into each other’s ears.

The damnedest thing is that they used to be so close, as close as two palms slapped together in a brother’s greeting to a brother. They were not equals. More a young pupil: Lewis Ferdinand Alcindor of UCLA, and Wilton Norman Chamberlain, the old master and man of the world, most lately set up in Los Angeles. But they’d known each other well from Harlem summer playgrounds, when Lewis was just a growing boy from Power Memorial High School and Chamberlain long since the big man and big name in professional basketball.

So often you could see the older man together with the youngster, and Chamberlain appeared to have a deep, real, and abiding interest in Alcindor, who inevitably would be a pro, and, if Wilt was still there when it happened, his rival.

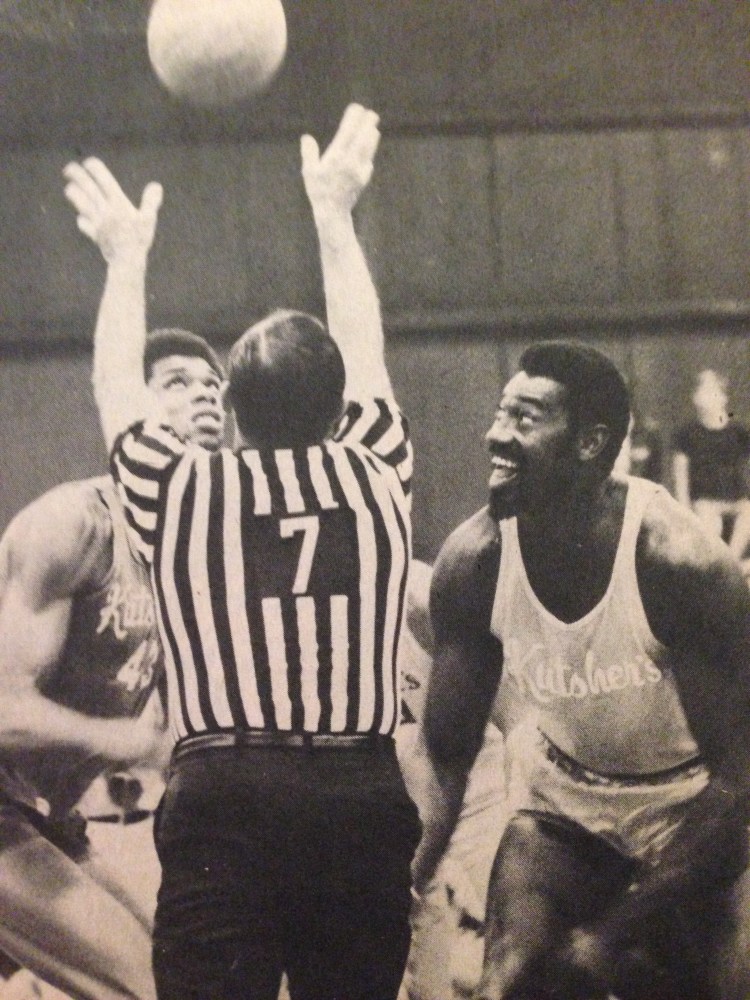

Once for instance, Alcindor came up to Kutsher’s Country Club in Monticello, N.Y., where each August they play the NBA All-Star game originally begun by Jack Twyman to help raise money for Maurice Stokes, the former Cincinnati Royals’ star who became a paraplegic. Stokes has since died. But the game is still played in his memory, and there is the memory of the first time Chamberlain and Jabbar went head-to-head, mano a mano, to be more exact. When Lew was about to turn pro, and Wilt was going to give him something to remember—at least let him know that it wasn’t going to be as easy in the NBA as it has been through four years of high school and college.

People began to get the idea that night that things inevitably had to change. Friendship was only skin deep. But competition was their lives and does not wipe away the driving force of one’s existence simply because some young man comes along and you like him.

Chamberlain did like Alcindor, make no mistake about that. You’d see them together in various places, and it was as though Wilt wanted to ease the way for the big kid who at first was so shy and seemingly so awkward.

There was another day that several have spoken about since and have embroidered upon as time has gone by. It serves as a frame of reference to what once had been and now is so obviously and starkly changed.

Alcindor was still in college, and Wilt, who made it a point to spend time with the collegian when in Los Angeles, had asked Lew to come up to Kutsher’s with him merely to be a spectator at the Stokes game. Wilt was the attraction. Nothing could detract from that. He had been a bellhop at the hotel when he was younger, and each time he came back he was THE celebrity.

This time, Lew was with him but attempting to fade into the background. Chamberlain wouldn’t let him. Each time somebody came up to Wilt in the lobby, Chamberlain would make sure that his young friend would be introduced and included in the conversation.

“You know Lew Alcindor, of course,” Wilt said to those he knew well and should have known Alcindor. It was a little thing, part of the pattern of being the graceful big man, making the kid feel welcome and at home and a part of the scene that soon enough he would dominate.

Then came the day when Alcindor participated in his first Stokes game. He had graduated from UCLA in June, and by August basketball fans could hardly wait to see how long it would take before he would become as overpowering in the pros as he had been in college. It was August 1969.

Remember it well because that might’ve been the beginning. Wilt watchers don’t think so. They think it took a while and much more of what Chamberlain considers a pointed personal affront. Nevertheless, this was the start. And in our set, we mark it as the beginning of the break that has led to the bitterness that exists between the two one-time close friends. Maybe at the height from which both operate, friendship is a luxury that even players who receive over $300,000 a season cannot afford.

Anyway, the game started in a completely informal atmosphere that is the climate for all off-season exhibitions. But the crowds were so heavy outside the gym at Camp Anawana that one could only assume that even the spectators knew there would be something special. Half the spectators were not yet even inside the gym when it happened.

Wilt went down low as the team took the ball on the offense in this 11th annual Stokes game. And as he moved laterally across the court with Alcindor following behind him in a defensive position, Chamberlain took a pass, bent low with flexed knees, made no effort to feint or fake, just stretched himself upward and slammed the ball through the hoop with a stuff shot.

At the press table, one guy looked at another and couldn’t suppress a grin. “The old man has decided the young man must be taught something early,” he said to his neighbor.

Maybe Wilt thought as much. He didn’t laugh aloud, but a look of smug self-satisfaction seemed to autograph his face as he jogged back up the floor following his basket. Alcindor’s face remained expressionless. It is a posture the tall young man has mastered through the years of growth as his mind became accustomed to the knowledge that he would always be considered different from other people, even though he would prefer to be considered the same. Nobody could tell by the look of him that Lew had made up his mind that he must pay back in kind as swiftly as possible. But the determination was there, and the opportunity came sooner than most expected.

The ball moved to the other end of the court, and Alcindor stationed himself to the right of the basket. He feinted away, then went toward the hoop, hesitated to take a pass, gave Wilt a move. Before Chamberlain could react, Lew dunked his own shot against his veteran opponent, easily with as much flourish.

“Something tells me,” said the second newspaperman to the first, “that Alcindor has answered Chamberlain’s message. It looks like they’ve now told something to each other.”

They had, indeed, but what most people could not have known was that this seemingly insignificant scene was just the beginning of so much more that was to come. Few people have ever seen it on the surface, and neither Chamberlain nor Kareem Abdul-Jabbar will ever admit it.

But their friendship curdled, and while hate may be much too harsh a word to define their relationship, they scarcely embrace each time they meet. Except on the court where they must face each other professionally, the two giants make every effort to avoid being in the same place where they would have to pretend continued friendship and brotherhood. They dislike each other intensely now. It is a condition that has evolved. It is hard to pin down anything specific, although a case can be made that these are two men competing to be the best and both are subject to the weaknesses that afflict every man—jealousy, resentment, selfishness, vanity, pride.

They would have fallen apart in any event because of their difference in age and the tremendous variance and lifestyles. Wilt is the swinging bachelor, living in his million-dollar eyrie on the top of the California mountain, throwing parties, being part and parcel of those who are described as the beautiful people. Wilt enjoys what he has made of himself and indulges himself in the wealth he has earned.

Abdul-Jabbar, on the other hand, is married and the father of an infant. He is much more introspective and much more secretive. He has adopted Islamism as his religion and has gone to Harvard to study Arabic. He is earning something between $400,000 – $450,000 a year under a new four-year contract with Milwaukee, which makes him higher paid than Chamberlain. Wilt renegotiated his own pact with owner Jack Kent Cooke for over $300,000. It has been one of the touchstones of Wilt’s career that he must be the highest-paid, yet this is not the bug that is under his skin about Abdul- Jabbar.

What does bug him is not that Kareem has come on so fast, and Wilt knows that inevitably he must go downhill, but that the young man to whom he felt he had been so kind returned that kindness with unkindness. And to Wilt that was the unkindest cut of all.

We’ve gone to several people close to each of these two strange men and had them come as close as they can to pin it all down to its basics. What comes out is this:

Wilt is hurt. Not professionally, but personally. He feels that Alcindor cultivated him and used him when he needed him. And then when Lew had it made real big, he started to snub the older man who considers himself the younger one’s friend.

According to some of the stories we are told, Wilt went out of his way to make Alcindor welcome when he was at UCLA and finding Los Angeles difficult to swallow. Chamberlain would work with him, giving him basketball tips and pointers and had him over to his house so that loneliness wouldn’t become too much of a burden.

Everything really went well, and their friendship developed as well as it could until about halfway through Kareem’s second season with the Bucks when he appreciated that he had it made a really big. That, of course, was the season in which Milwaukee won the NBA championship, defeating Los Angeles four games to one in the Western Conference finals.

At that point, their relationship had deteriorated to little more than surface friendship. Wilt had reached the conclusion that Lew had not really been a friend but had seemed to be one when he needed Chamberlain. When he no longer did, Lew allowed their feeling to cool.

In other words, Wilt concluded he had been used.

It doesn’t have to be true. It only matters if Wilt thinks it is true because there are several different kinds of pain, and if a man thinks he hurts, then he does hurt.

What this means, of course, is that every game between the Bucks in the Lakers will be wars, not that they wouldn’t have been anyway, but with Chamberlain feeling that Kareem had played him for a chump, Wilt’s going to try to play the game like a champ. He knows he can’t go out all the way all the time, not at his age, not with his knees. But Kareem should bring the cream out of him. The milk of his human kindness has been curdled.

Bob your blog is a hidden jam. Thank you so much for all the amazing uploads! just loads of great basketball history content! keep it up!!

Yossi,

Tel Aviv,

Israel

LikeLike