[It started with LeRoy Ellis, the Baltimore Bullets’ starting center. Then came Lakers’ Bad News Barnes, and Chicago’s young center Erwin Mueller. They were the first NBA veterans to cross the line and sign contracts with the brand-new ABA in the spring of 1967. Their NBA bosses cried foul, filing immediate injunctions and threatening multi-million-dollar lawsuits. The three vets jumped right back to the NBA, though for higher salaries. So did a few other NBA opportunists in the weeks ahead.

That left it to the Warriors’ superstar Rick Barry to jump to the ABA’s Oakland Oaks and serve as the test case of the NBA’s one-year option clause and its legality. If the verdict favored Barry, who was amply represented by ABA lawyers and didn’t have to worry about his legal bills, the option-clause would be debunked and, conceivably, he could play the next season for the Oaks.

That, of course, didn’t happen. A California judge sidestepped the possible antitrust violations of the NBA option clause and ruled that it was an element in the contract that Barry’s willingly signed. Thus, he had to honor the Warriors’ additional one-year claim on his services.

However, the judge clarified that the option was valid for one year only, a win for the ABA. Until then, the NBA had bluffed that its one-year option, following in the footsteps of major league baseball’s Supreme Court-sanctioned reserve system, could be renewed annually into infinity. There was no existing case law to counter the NBA’s position.

And so, Barry famously sat out a season before joining the Oaks the following year. While Barry sat, though, some end-of-the-bench NBA players jumped to the ABA and joined the action the very next season, completely disregarding the option year. Why? The affected NBA teams (mostly expansion San Diego and Seattle) didn’t want to be bothered with the legal costs of bringing back marginal players, who may or may not make their opening-night roster.

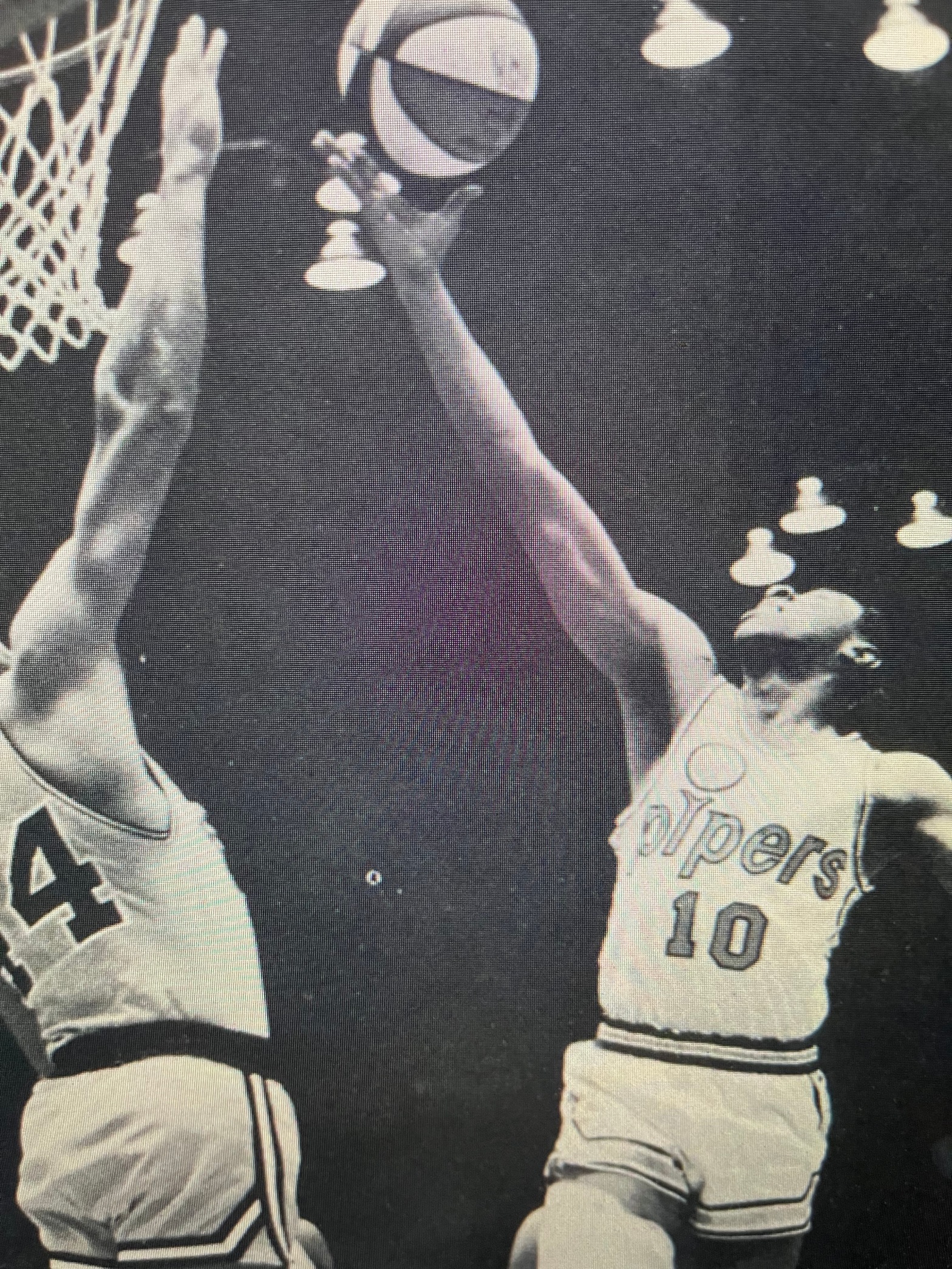

One of these lucky ducks was guard Chico Vaughn, who played alongside Connie Hawkins on the ABA’s first-year champion Pittsburg Pipers and also made the all-star team. There isn’t much written about Vaughn, who passed away in 2013. But this column from the January 17, 1968 edition of the Pittsburgh Press tells his story and briefly explains how Chico beat The Man. On the call is the Press’ venerable Roy McHugh, who died in 2019 at the age of 103.]

****

Today, as on most days, Chico Vaughn and the rest of the ABA Pittsburgh Pipers were up very early. Their flight to Indianapolis left at 8:30 a.m. What Francis Scott Key would see by the dawn’s early light at any big-city airport is a basketball team.

One morning last week, Chico Vaughn nearly missed another 8:30 flight, this time to Minneapolis. Chico had ordered a 6:30 a.m. call—he lives at the Carlton House Hotel—and he picked up the phone when it rang, but then decided to close his eyes again. Just for a second. It took a prolonged fastbreak out Route 22 to get him to the airport at 8:25.

And he still finished the week owing sleep to himself. Requisitioned for the All-Star game, Chico and Connie Hawkins spent the whole previous night in their tourist-section seats on a plane. These two played basketball last week on six consecutive nights in five different towns, hitting Indianapolis twice.

Chico, the Pipers’ old pro, knows every airport in America, not to mention the motels and arenas. Starting with the St. Louis Hawks in 1962, he has had five years of it now.

There are easier ways to make a living, but possibly not in Tamms, Ill., where Chico was the star of the high school team. What Tamms had to offer for Chico’s father was a job with a pick and shovel.

Tamms, population 550, is a country town above Cairo, where the Ohio flows into the Mississippi. Little Egypt, that part of southern Illinois is called, and the land stretches out flat and desolate, scarred by strip mines.

Chico could hardly wait to leave it. Bobby Joe Mason as from Centralia, just north of Tamms, and Bobby Joe had gone off to play on the basketball team at Bradley University in Peoria. Chico, sifting through the scholarship offers, felt that Bradley was for him, and with summer school on his mind, he shook the dust of Tamms from his sneakers in June.

But Chico didn’t like it at Bradley, and don’t ask him why for he is not really sure. He stayed on the campus a week and departed for Dayton. This was better. An obliging Dayton recruiter fixed Chico up with a job in a bakery—something, you know, to make bread—and the summer went by agreeably.

Chico was all set to play basketball at Dayton—and then he went home for a visit. And who should be on his doorstep but the new coach at Southern Illinois, Harry Gallatin. Such was Harry Gallatin’s persuasiveness that they never saw Chico in Dayton again.

Southern Illinois was where Chico acquired his present nickname. Up to then, by courtesy of a sports writer on the Cairo Evening Citizen, it was Sweet Charley. But at SIU, Chico says, a basketball player named Kenneth Farmer took a strong dislike to the sound of Sweet Charley. One day, Kenneth Farmer was reading a book, and there was a character in it named Chico. One thing led to another.

“Now everyone thinks I’m a Puerto Rican,” says Chico.

After SIU, Chico wound up with the St. Louis Hawks, where the new coach, by a not very remarkable coincidence, turned out to be Harry Gallatin. Their association was not destined to continue much longer, for owner Ben Kerner, as Chico points out, “is used to firing people.” But Chico got along well with the next coach, too—Richie Guerin. “All I had was a jump shot,” says Chico. “Richie Guerin taught me how to drive.”

He taught him to watch the baseline, too, after Paul Neumann of the Syracuse Nationals was driving it on Chico one night. “If that guy keeps going around you,” said Guerin at halftime, “you’ll sit on the bench the rest of the season.” Neumann never scored another point.

But the night before Christmas 1965, the Hawks traded Chico to the Detroit Pistons for Rod Thorn, and Detroit reminded Chico of Bradley. He didn’t like it, and he didn’t like the coach Dave DeBusschere. So he asked to be put in the National Basketball Association’s expansion draft. That was how Chico happened to be in San Diego one day last summer.

He went out there to sign his contract with the expansion San Diego Rockets. “But the only person I saw,” he says, “was a little ol’ publicity man. And they didn’t keep their word about the contract. There was supposed to be a job for me, a place to live. Well, I stayed in San Diego a week, and I never heard a thing about either one. And Jack McMahon, the coach, was out of town.”

Chico called information and asked for the number of the Pittsburgh basketball team. He did not know that Pittsburgh was called the Pipers, but he knew that his friend Joe Strawder of the Pistons had jumped to Pittsburgh. When owner Gabe Rubin answered the phone, Strawder was sitting across the desk from him.

They never saw Chico in San Diego again. Strawder? He’s back in Detroit. Gabe Rubin suspects that he sneaked out of Pittsburgh on a flight in the middle of the day.

[In our next post, we’ll take a look at what happened to Joe Strawder.]

Sir,thanks for your post!By the way, do you have any story of Ralph Beard?I would like to know what Beard was like before he was banned from the league.

LikeLike