[I recently had a conversation with a gentleman, now in his 90s but still sharp as a tack, about UCLA basketball and the John Wooden era. He did his fair share of grumbling, mainly because he’d been affiliated with rival USC basketball in the 1960s. Some of his grumbling was about Wooden, whom he claimed got more credit than he deserved. His point was Wooden borrowed a lot from other coaches, didn’t do much recruiting, and didn’t really bond with his players off the court.

Debatable? Sure. But it’s clear that Wooden, as strictly a college basketball coach and molder of men from endline to endline, didn’t do much to help his seniors prepare for their pro basketball careers. That wasn’t a character flaw. It came with the territory back then. College coaches, certainly with some exceptions, steered clear of all-things pro basketball. It simply wasn’t in Wooden’s job description and could lead to public misperceptions and possibly an NCAA scandal (though my 90-year-old claims it was common knowledge back then in the USC men’s basketball office that UCLA was protected from any NCAA snooping. Its AD reportedly was buddies with the NCAA’s lead investigator.)

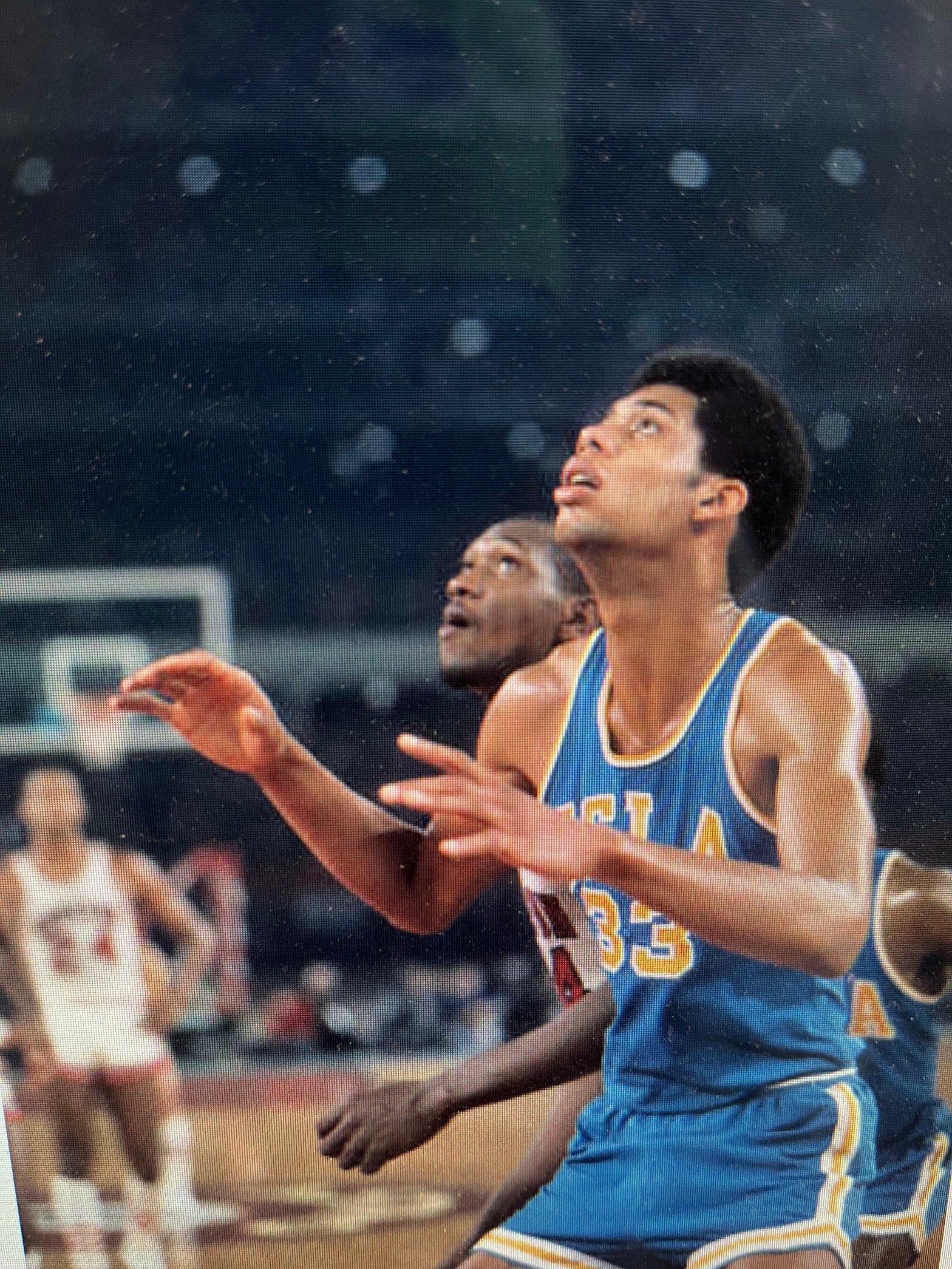

Wooden’s principled guidance and background in early pro basketball would have come in handy in the winter of 1969. His star center Lew Alcindor was projected to be pro basketball’s “first million-dollar baby,” and the public hype and pressure that came with imagining his future sports fortune dogged Alcindor just about wherever he went. They also put him and his progressive ideas under a microscope during the 1960s and its troubled social times.

The article below, from writer Francis Rogers and published in the magazine Sports Review’s Basketball 1968-69, captures the hype well. Though the article never mentions UCLA super-alum Sam Gilbert, it provides a good sense of why his professional services were needed to help launch Alcindor-turned-Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on an NBA career for the ages, including his now just-fallen NBA all-time scoring record of 38,387 points. Congratulations, Lebron!]

What happened to Lew Alcindor a couple nights in New York last winter went a long way towards answering the question of whether he will be professional sports’ first million-dollar contract holder.

In late January, UCLA visited Madison Square Garden, and Lew came up against Jack Donohue, his old high school coach from Power Memorial Academy in Manhattan. Donohue had watched over Alcindor like a child of royal birth through his formative stages in high school, and the pair parted company from Power Memorial at the same time. Alcindor headed west to UCLA, and Donohue took over the coaching reins at Holy Cross.

Now here they were squared off against each other for the first time in their lives. “How will you handle Alcindor?” Donohue was asked before the big game.

“We’ll work on his legs,” replied Donohue with the look of an altar boy on his face. “You see, we have this 5-feet-8 kid who will pick up Lew at midcourt. The little guy will have this axe, and as soon as Lewie crosses the center line, wham, he gets it. Now, if the referees are looking the other way, we’re in business.

Either the refs were watching or the kid forgot his axe, for Holy Cross became just another win on UCLA’s happy record, and nobody stopped Lew, with or without an axe.

Then, two nights later, UCLA faced Boston College, which is coached by Bob Cousy, who has a few pro credentials. “How you gonna stop him?” somebody asked Cooz.

Up to this point, Cooz had never seen Alcindor play, but had heard a few things about him from time to time. “Defensing Alcindor is out of the realm of coaching,” Cousy answered. “You can’t rely on some miracle formula. There just isn’t any. All I want my kids to do is play the best game they are capable of playing.”

And then, as if by some brilliant afterthought, Cooz added, “Basketball is an emotional game. Who knows what kids can do? We have to do what we do best.”

What he may have been referring to was the beating on the post given to Alcindor by the Boston post man, Terry Driscoll, who at 6-feet-7 and 215 pounds, allowed Alcindor a six-and-a-half-inch height and 15-pound advantage. Driscoll, like Alcindor, was a junior at the time and simply did what he did best. He began a light tattoo on Alcindor’s ribs in the early minutes of the first half and increased it in crescendo as UCLA increased its lead. By the middle of the second half with the Bruins pulling away, Cousy called a timeout.

“I told him (Driscoll) to stay in there close and do what he could to stop Alcindor,” said Cousy later, after UCLA simply wore down Boston College and won. Then, in an afterthought, he said half apologetically, “That kid (Alcindor) wants to play pro ball, and he may as well know what it’s all about.”

Cooz had wanted to show Alcindor what the pros “were all about,” and Lew had responded quietly, “I know, I know,” with a set of flashing elbows. Don’t let anybody tell you that Lew Alcindor isn’t ready for the pros, but the question of what it’ll cost the pros to get him is a horse a bit different color.

Three things could keep Lew from becoming pro sports’ first million-dollar baby: (1) The demise of the ABA, (2) Lew himself, and (3) Joe Willie Namath of the New York Jets. What has Namath got to do with Alcindor making a million bucks?

Well, one of the stories making the rounds of Toots Shor’s [restaurant] prior to last football season claimed that somewhere . . . either in the Jets’ safe or in possession of ex-owner and Joe’s benefactor Sonny Werblin, there is a five-year contract with a million bucks etched on it, and the name inscribed thereon is Joe Willie Namath.

Now the Jets will say this is ridiculous for when Joe’s new contract was being negotiated, the Jets were having a lot of trouble signing an unusually high number of unhappy veteran players, and the last thing they wanted leaking out was the fact that anybody was getting a million bucks.

If Namath isn’t the first one-shot millionaire in sports, then what about Lew? Can he be the one? Well, he could be, except for two other possibilities . . . Lew, himself and the possible demise of the ABA. If the new loop folds, as many basketball people feel it will, what effect will that have on Lew’s bargaining power?

Well, roughly, it would have the same effect that a merger between Ford and General Motors would have on the auto Industry. The ABA may not be solid, but it is still the only competition that the NBA has in the talent marketplace. Right now, the ABA is so pressed that perhaps only one thing, or better yet, one person can save it: Lew Alcindor. But the ABA will have to get up a million for him.

With the ABA removed as possible negotiators for the tall-and-talented Alcindor, you can bet that the NBA owners will get their heads together to hold down the price. How can they do this?

Quite simply! The cellar dweller of the 1968-69 season will get draft rights to lanky Lew, and they’ll have to negotiate his contract with everyone from Harry Edwards to Adam Clayton Powell.

When the hassling is over . . . and that team STILL can’t sign Lew, they’ll throw up their hands in despair and say, “We are at a stalemate.” Then they’ll try to peddle their rights for Lew to another team whose geographical location or playing personnel move more to the big Bruin.

Unless that team comes across with a million bucks, it too will throw up its hands in despair and Lew will look like the most ungrateful rookie in sports. He’ll either sit out as the tallest martyr in history—or sign. Naturally, all this can be avoided if the ABA survives, for in that case the bidding will start at half a ”mill” and move steadily upward.

What about the part that Lew himself will play in his quest for a million bucks? Well, this could be the deciding factor. Lew has a tendency to join crusades, to stand up and be counted. Lew’s hang-up seems to be that other people want to avail themselves of the seven-foot height God bestowed upon Alcindor. If he was 6-feet-2 and could do only modest things with a basketball, it is quite unlikely that he would mean as much to Harry Edwards’ crusade and quite unlikely that Lew Alcindor would be asked for interviews on national TV.

But Lew is over 7-feet-1, and he has stood up to be counted and asked to appear on national TV interviews. One such interview last summer brought the roof down on Lew, who included among his comments, “. . . yeah, I live here (the USA), but this isn’t my country.”

It sounded to a sensitive American audience like pure Cassius Clay, and the public reacted quickly. The remarks were accepted by them as they wanted them to be. They wanted them to sound like a belligerent message from a gangly, ungrateful Black kid. They wanted to believe that he was disclaiming his country.

The basketball fans among them wanted to find some reason to tear down the magnificent achievements this young man had wreaked upon their game. They resisted the changes he was forcing upon the game of basketball, just as they had resisted the changes that Wilt Chamberlain before him had forced upon the game. The sensitive young man’s remarks had been the opening they had been waiting for.

It mattered little that he had a right to his views, whether they were expressed in the quiet of his UCLA dorm or over a TV hookup. It also mattered little to his critics that his words were grossly misunderstood. Rather than being a polished speaker, he was victimized by semantics.

Don’t think for one minute that Lew Alcindor is any bumblebrain. Far from it. He is a young man who is destined for great success in, perhaps, any field of his choosing. His most likely choice will be pro basketball, at least for the time being, but Lew has far too much class to become a drawing card freak. Lew Alcindor has things to do with his life . . . exciting things, like bringing a new respectability to his race . . . seeing that little African children get fed properly . . . seeing that little Afro-Americans are housed in homes, not pens.

And, it is just possible that Lew Alcindor may use pro basketball for the springboard to bring many of these accomplishments about, and if he does, somebody at some time will have to pay him a million bucks. He has the qualifications. Experts say he enters pro basketball with more strength, greater talent, and more experience than did Wilt Chamberlain. He also enters the game at a time when it is financially sound.

Elvin Hayes has already got half a million. Alcindor can get that on one foot.