[Everyone has their favorite vintage basketball books. One of mine is David Wolf’s Foul!: Connie Hawkins Schoolyard Star, Exile, NBA Superstar, published in 1972. More than fifty years later, I can still pull Wolf’s classic off the shelf, flip it open to a random page, and instantly get lost for the next hour in its flood of memories. Wolf’s excellent reporting really has stood the test of basketball time.

But before Wolf hit the bookstores with Foul!, he hit the presses with a widely-read profile of Hawkins for the May 16, 1969 issue of Life Magazine. It’s this long article that heaped extra pressure on the NBA and its lawyers at exactly the right time. Wolf’s solid reporting got people asking questions, and the NBA Commissioner Walter Kennedy to reconsider Hawkins’ lifetime ban for allegedly once being an “intermediary” who introduced gamblers to other college players. After some further arm-wrestling among the NBA owners, Hawkins finally got the needed votes to join the NBA in June 1969 as a member of the Phoenix Suns.

Here’s Wolf’s vintage article in full. It’s long, and your time is precious. So, let’s stop the intro here, and get on with the show.]

****

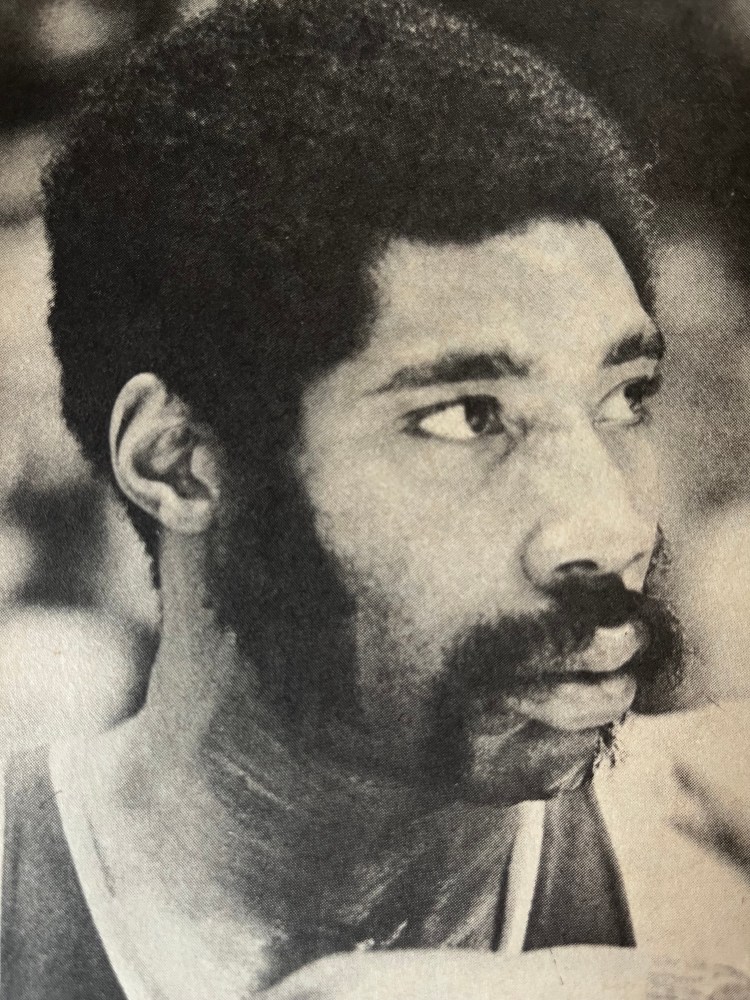

He is six-feet-eight inches tall, and he does things on the basketball court nobody else his size can equal. He moves with disciplined grace—controlling the ball with one massive hand, dribbling behind his back, passing with the flash of a Globetrotter, and making jump shots from 20 feet out. One special move always brings the crowd to its feet. He slithers close to the basket, wards off defenders with his free arm, leaps high into the air, and dunks the ball with a one-handed flourish that rattles the backboard.

His name is Connie Hawkins and, according to top professionals who played against him in summer tournaments, he is one of the five greatest players in the world, a mixture of Bill Russell, Oscar Robertson, and Elgin Baylor. And those who praise him loudest play in the National Basketball Association, the sport’s only real major league. “Connie Hawkins would be a superstar in the NBA,” says Willis Reed of the New York Knicks. “All the guys know it.”

But Hawkins has never played in the NBA. One of 47 college players marked forever by a game-fixing scandal eight years ago, he is anathema to the league. In 1961, New York District Attorney Frank Hogan labeled Connie—then an 18-year-old freshman at the University of Iowa— an “intermediary” who introduced fixers to ballplayers. For his services, he was supposed to have been paid a total of $210 by gamblers [today, $2,143.] He has been an outcast ever since, playing in obscurity—even though he was always the high scorer and most valuable player—in whatever pro league popped up to challenge the NBA.

He also acted the clown with the Globetrotters for four years. This past season, he played to the sparse audiences who follow the Minnesota Pipers of the struggling American Basketball Association, while earning a fraction of what he could command in the NBA. He is happy to be playing anywhere, though. Basketball is the only thing he knows, the only thing that really matters to him.

But he wants to clear his name and play in the NBA. Two years ago, he filed a $6 million treble-damage suit against the big league, charging that it is a monopoly and has conspired to deprive him of his right to earn a living in his chosen profession. The case will go to trial in the fall. It is a complex antitrust suit, and no matter what the court may rule, evidence recently uncovered indicates the Connie Hawkins never knowinglyassociated with gamblers, that he never introduced a player to a fixer, and that the only damaging statements about his involvement were made by Hawkins himself—as a terrified, semi-literate teenager who thought he’d go to jail unless he said what the DA’s detectives pressed him to say. Hawkins, in other words, did nothing that would have justified his being banned by the NBA.

One night last winter, after Connie had scored 47 points against the Indiana Pacers, he slipped into a darkened bedroom and stared a long time at his sleeping children, Shawna, 5 ½, and Keenan, 1 ½. Then he went into the next room, poured a rum and Coke, and sprawled across a double bed. His body was sore, as it always is after a game. He’s a natural forward—at 200 pounds much too thin to be playing center. He gives away up to 70 pounds and takes a savage beating in the pivot because that is where the Pipers need him.

But it isn’t his way to complain. Hawkins is a warm, gentle man of simple tastes. His offseason home is in the Pittsburgh ghetto because he is comfortable there. In a militant time, he’s a Black man who can describe himself as “colored” and worry that his wife’s Afro wig is “too Black-powerish.” One night recently, after much prodding, when he finally asked the waiter to stop calling him “Boy,” Connie whispered to a friend as the old man walked away, “I hope I didn’t hurt his feelings.”

The years of suspicion and disappointment have increased his sensitiveness and reticence. “I never talk to anybody about the scandal,” he said, slowly sipping his drink. “It’s been eight years since I’ve really talked about it to anyone, but my lawyers and my wife—and I don’t like to do it with them. The players understand. They never mention it.”

Hawkins fell silent a moment, then repeated a question: “How do I feel?” There was a longer silence until suddenly he sat erect and the words came rushing out: “How do you think I feel? I know how good I am. But ain’t no way I can get a chance. It’s like havin’ the water running and your hands tied so you can’t turn it off. I know what you think. You think I was mixed up in it. But I wasn’t, man, I swear I wasn’t . . .”

His story is hard to believe—unless you understand what a slow naïve kid Hawkins was nine years ago when he met the fixers, Jack Molinas and Joe Hacken.

Connie grew up on a Brooklyn Street where whores, pimps, and junkies crowded the sidewalk. There were six children in his family. His father left when Connie was 10. His mother was going blind. He slept in a single bed with a brother, and his only pair of slacks grew shorter each year.

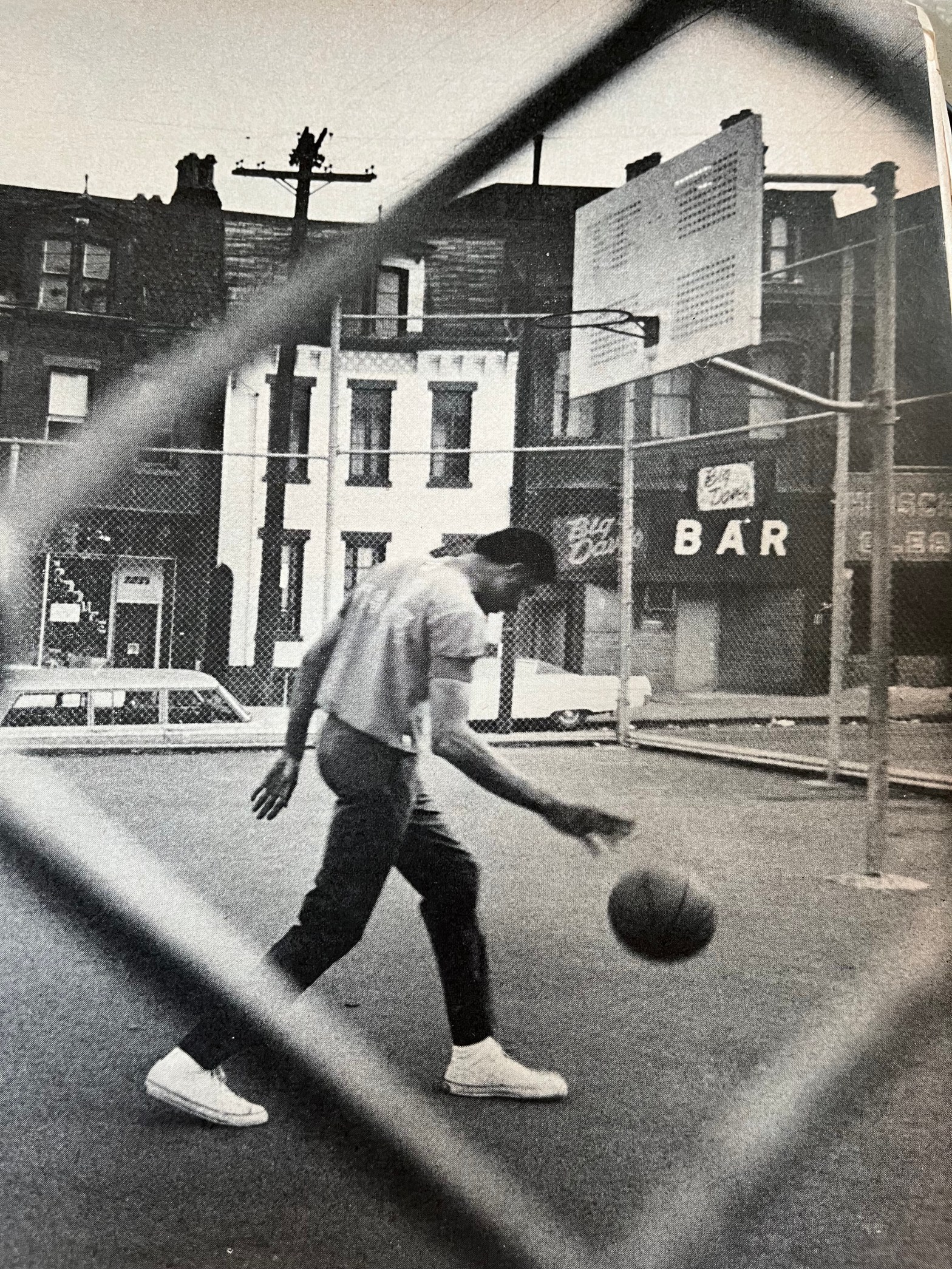

Yet Hawkins was never in trouble with the law. His life was the playgrounds and schoolyards of Bedford-Stuyvesant, where pros, collegians, and high school kids went three-on-three until it was too dark to see the hoop. Before he turned 18, he had gone against such visiting stars as Oscar Robertson, and Wilt Chamberlain.

Connie graduated from Boys High with a general diploma—something they give to kids who do little more than stay in school for four years. He didn’t have a driver’s license because he couldn’t read well enough to understand the written test. He looked at a newspaper only when someone told him his picture was in it.

He was in the papers often. He was 6-feet-7 then and probably the finest prospect ever to come out of the city. He was the super stud of 1960—the player everyone wanted—and every athletic factory worth its season-ticket plan was after him. Typical of the annual recruiting sweepstakes, more than 200 colleges were willing to overlook his grades and besieged him to enroll. The summer after graduation, the boy who in high school had collected soda bottles to cash in for lunch money was being flown to schools all over the country. Several institutions talked about monthly salaries. One guaranteed him a handsome weekly fee for keeping its football stadium clear of seaweed—which wouldn’t have been too trying since the college was 1,000 miles from the nearest ocean. Back home, promoters paid “expense money” when he played in amateur tournaments, and recruiters took him to dinner and left $10 bills under his napkin.

One day that summer of 1960, Connie was playing on the courts at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, when a tall man with dark, receding hair walked over and extended a hand that was almost as large as Connie’s. “Hawkins,” he said, “I’m Jack Molinas.”

Molinas, 6-feet-6, had been an All-America at Columbia and a star in the NBA. But midway through the 1954 season, he had been banned from the league for betting on games. Now he was a successful lawyer, player-coach of an Eastern League team, and, at 28, still among the city’s top playground ballplayers.

But Molinas had another interest. He was the mastermind of a nationwide gambling ring that was in the process of paying 36 college players $70,000 to fix 43 games. He used the playgrounds to meet players. It seemed anything but unnatural to the young athletes when the older, affluent Molinas picked up the dinner tabs after tournament games. Connie, who was 12 years old when Molinas was booted out of the NBA, had never heard of his expulsion.

Connie had never heard of many things. As the detective who picked him up in Iowa eight months later was to learn, Connie didn’t even know what a “point spread” was. “I just thought Jack was a nice guy,” Hawkins recalls. “He’d buy us food, drive us home from the beach, and lend us his car. One time, he told me he knew how hard it was for poor kids their first year at school and, if I needed help or money, just let him know. He said he liked me.”

One night in August, before a game, Molinas invited to his law office Connie and his friend Roger Brown, who was regarded by college recruiters as New York’s second-best prospect. There, he gave them $10 each for transportation and dinner and introduced them to a man named “Joey.”

“Jack said he was a ‘client,’” Connie recalls. “Molinas and Roger left the room, and Joey started talking about basketball: who was better Wilt or Russell? Then he asked did I know any good college players? I told him Wilky Gilmore of Colorado, Vinnie Brewer of Iowa State, and some others. Then he asked could I introduce him to them sometime. I said ‘sure.’ I thought he was just another New York basketball nut.”

Fans are always asking to be introduced to basketball stars. But Joey wasn’t your typical fan. He was Joe Hacken, a Molinas lieutenant with nine bookmaking convictions. Connie had never heard of him.

At the end of the summer, Connie finally halted the bidding war for his services by selecting the University of Iowa. But his academic record couldn’t qualify him for an athletic scholarship under Big Ten rules. He could, however, be admitted on probation if he paid his own way. An Iowa alumnus got him a job at a filling station. Whether he ever showed up for work is questionable. But the paycheck always showed up, and it allowed him to cover his tuition, books, and board, and still have something left over. The athletic department surrounded him with tutors and hoped for the best.

It was while back in New York during Christmas vacation that Connie next saw Molinas at a game in Madison Square Garden. He invited Connie to a restaurant, and there made a call. Hacken arrived 10 minutes later. “We talked basketball for a while, then Joey asked if I’d call Vinnie Brewer at Iowa State and introduce him,” Connie recalls. “I said, ‘okay.’ I called, but there was no answer. Hacken said: ‘Never mind. Forget it.’ Later, Jack gave me cab fare.”

Several days later, Connie had a problem. Before leaving for New York, he’d been paid at his ”job.” The money was to cover his dormitory fee for the next semester. But Connie had blown $200 in New York. “I felt I couldn’t go back to school without the money,” he says. “I was real desperate. Then I remembered what Jack had said about if I ever needed help. He was the only person I knew who had that kind of money. I called him up and asked for a loan. He brought the money to my house the day before I went back to school.”

Early in the spring of 1961, while Connie was finding the second semester’s courses at Iowa just as mystifying is the first semester’s had been, detectives from the New York county DA’s office picked up a former public school teacher named David Budin, who admitted arranging several fixed games. Then he began reciting names.

One of the names was Connie Hawkins. Budin informed the DA that Hacken had told him: “Molinas has Brown [Roger Brown was at Dayton University] and Hawkins in the bag.”

That was all. There were no specifics. Budin had never met Hawkins. Hacken now denies mentioning Connie to Budin. But it was enough for the DA’s office to dispatch Detective Anthony Bernhard to Iowa.

On Thursday, April 27, 1961, Connie was summoned to the fieldhouse by Iowa coach Sharm Scheuerman. Bernhard was waiting. Hawkins told the detective he had been with Molinas about a dozen times, but he could identify Hacken’s picture only as “Joey.” Bernhard said he wanted Connie to come to New York to help with the investigation. He promised Scheuerman that Connie would be back in three days.

By the time Hawkins returned to Iowa—two weeks later—his life was a shambles.

Bernhard put Connie under protective custody in New York and registered him at the Prince George Hotel. On Monday, the detective continued to question Hawkins at the DA’s office. Tuesday, Bernhard was joined by Detective Frank Marone. Bernhard estimates that, during those first six days he was with Hawkins, the youngster was interrogated at least 20 times. And Hawkins’ story was consistent each time. He told of the expense money, free, meals, and the $200 loan from Molinas; of a car Connie and Roger Brown borrowed from Molinas one night; of the unsuccessful phone call to Vinnie Brewer; and, of the meetings with “Joey” Hacken.

Bernhard was experienced in sports investigations. Working as an undercover man, he had helped break up the Frankie Carbo boxing mob, had testified before the Kefauver Commission boxing hearings in 1960, and was later to be awarded a commendation for meritorious police work in the basketball probe. He resigned from the force in 1966 and is now an industrial security consultant. He is one of the few detectives on the case who can speak freely today.

Although Connie no longer remembers it, Bernhard says Hawkins also disclosed that Joe Hacken had asked him if Vinnie Brewer or any other college players might be interested in making money; and if so, Connie could pick up a few bucks by providing introductions. But says Bernhard: “The kid also told me Hacken had explained he was organizing an all-Black team for next summer. My notes were a summary of five hours’ questioning, and I didn’t include it [the explanation]. Maybe I didn’t believe him. But later, Hacken told me that’s exactly what he had told Hawkins.”

Thus, for six days, Connie had insisted that Molinas and Hacken never mentioned fixed games or gambling, and that he hadn’t introduced any players to them. If he had stuck to this story, he probably would be in the NBA today. But suddenly his story changed. In the next eight days, Hawkins swamped himself in incriminating statements, confessing knowledge of everything but the Great Train Robbery.

****

The statements that Hawkins is alleged to have made between May 3, when his story changed, and May 10, when he testified before the New York County Grand Jury, are confused and contradictory. Today, eight years later, there is nothing to substantiate any of his injurious admissions. Both Hacken and Molinas subsequently served time. Molinas is still on parole. It would hardly be prudent for either to contradict DA Frank Hogan today. But both say Hawkins is completely innocent. And there isn’t a single player who says Connie Hawkins tried to introduce him to a gambler. In fact—with the exception of Dave Budin’s “in-the-bag” reference—no one ever told the investigators anything damaging to Hawkins except Connie himself.

What is Connie supposed to have said? According to notes filed at the DA’s office, Hawkins managed four different versions of the only player-gambler “introduction” he was ever to admit. He told Detective Kenneth Wheaton that he tried to get Colorado’s star forward Wilky Gilmore to meet Molinas at a benefit game in Rockville Centre, Long Island, in the summer of 1960. Wheaton’s notes read: “Gilmore didn’t want to meet him . . .” Later, Connie told Detective Joe San Pietro that Molinas asked for the introduction, but that before Connie could reach Gilmore, Molinas had already introduced himself.

There is another set of notes on file. Inexplicably, they are unsigned, undated, and written in a handwriting none of the detectives now recognizes. There is a reason to believe that two or three other players were being interrogated with Hawkins when these notes were made. But the DA attributes to Connie all the statements in the notes, which include two more versions of the Wilky Gilmore incident.

First they read: “JM asked me if I knew Gilmore. Then—would he [Gilmore] be interested in making money? Yes, I introduced them . . .” Subsequently, the same notes, contradict themselves, saying, “I told Gilmore do you want to meet Jack? He said ‘no.’ I told Gilmore JM wanted to talk to him about making money. I told Jack he [Gilmore] didn’t want to meet him . . .”

Today, Maurice Wilkins Gilmore is a social worker in Stamford, Conn. He says the player who approached him in Rockville Centre was not Connie Hawkins. Gilmore detailed the incident to detectives when he was brought in for questioning during the DA’s investigation. “I told them the player’s name, and I gave the name before the grand jury,” he says. “I don’t understand how they got the idea it was Connie.”

The player mentioned by Gilmore now also admits making the introduction.

But Hawkins made other statements to the detectives. The record show that at least twice Connie said that Hacken told him he bet on games, wanted players to “work for me,” and that Connie himself could make “$500 if Vinnie Brewer cooperated.” On May 10, the day he went before the grand jury, Connie allegedly informed Detective Joe Nardoza: “JH told me they would get $1,000 apiece per game if they would cooperate in shaving points . . .”

Joe Hacken says he never told Connie anything about his activities—not even that he gambled. Why believe Joe Hacken? Tony Bernhard, who brought Connie back from Iowa has known Hacken since 1958, when the detective infiltrated Frankie Carbo’s inner circle and found Joey a fringe character in the boxing mob. “Everybody around Carbo trusted me,” Bernhard says. “Everybody talked to me. Everybody but Joey. He was the only guy in that deal who never said anything, because he didn’t trust anyone. So when Carbo went under, Joey walked away. There’s no way a guy like Hacken would have told a dumb kid like Hawkins anything. How did he know who Hawkins might tell? Of course, he was setting him up for fixing later, but he didn’t have to tell Hawkins anything then to do that.

“Another thing about Hacken. He won’t lie about somebody. That’s just the way he is. If you ask about a kid who was involved, Joey won’t bury him; he’ll just change the subject. But he says this kid Hawkins really is clean, that he didn’t know a thing. And Joey has nothing to gain by saying it. The last thing he needs is the spotlight.”

Also in the unsigned, undated notes, Connie is recorded as saying: “I asked Brewer in Iowa at a party if he knew Jack [Molinas], and he said yes. I asked if he was fixing games for Molinas? He said yes . . .”

However, if the DA believed what Connie is supposed to have said, he certainly would have hustled Vinnie Brewer in from Iowa State for questioning and put him in front of the grand jury. But the DA’s office admits it never questioned Brewer, and the records show he didn’t testify before the grand jury. Today, Brewer, an instructor with the New York City Youth Board, says, “I saw Connie once or twice in Iowa. And he never mentioned Molinas, Hacken, money, or fixes.”

These same unsigned, undated notes are the only source for Connie’s alleged admission that he received $200 from Molinas where he did not explain it was a loan. The detectives were sure it was a gift or a bribe until recently, when a few of them learned why Connie was afraid to explain how he was going to repay it. Connie’s older brother, who had promised to return the money to Molinas, was then working as a runner in the numbers racket—a fact Connie couldn’t very well tell detectives. Actually, Connie’s brother says today, by the time Hawkins was picked up in Iowa, the loan had been repaid.

Jack Molinas says the same thing. He is now on parole after serving four years in prison. A few weeks ago, he placed his glistening shoes atop his attorney’s desk, puffed a thick cigar, and talked about Hawkins. Wearing an expensive suit, wide paisley tie, and infectious smile, Molinas was the same picture of confidence and charm he had been until the closing days of his trial. He has abandoned his pretense of innocence, but not his sense of humor. “I don’t need the publicity,” he joked. “What can you write about me, except that I corrupted the youth of America?”

“Allegedly corrupted,” reminded his lawyer, a Runyonesque figure in a sharkskin suit, pink shirt, and huge purple cuff links.

“Of course,” said Jack, laughing.

But Molinas doesn’t laugh about Hawkins. “I never made any approach or gave him any reason to think games were being fixed or bets were being made,” Molinas said. “As far as that $200 is concerned, Connie called me in December [1960] and said he needed a loan or he couldn’t go back to school. I never expected to see the money again. Then one day, this guy walks into my office and puts $200 on the desk. He says he’s Connie’s brother. And that was well before the scandal broke.”

Connie’s last testimony was before the grand jury. Those minutes are privileged, but one detective speculates: “If what he told the grand jury is anything like what we have in our notes, the boy must have really buried himself.”

On May 23, 1961, the grand jury, indicted Joe Hacken. There was one count of conspiracy and 17 counts of bribery. Fourteen players were mentioned in the indictment. Connie was named in four of the 41 overt acts in the conspiracy count. Hacken was charged with giving him $10 in September, offering him $500 for introductions in September, meeting with him in December—surprisingly—giving him $200 in December. The $200 was not described as a loan, and there was no hint the money had come from Molinas. DA Frank Hogan told the press that Connie and Roger Brown were ”intermediaries” in recruiting prospects for bribe offers.

Why did Hawkins incriminate himself? “I was frightened,” Connie says. “I thought they were going to put me in jail if I didn’t say what they wanted.”

Frank Hogan’s detectives are among the most respected in the country. They are expert at prying confessions from people. Despite the fact that a confused 18-year-old confessed to something he had not done, Bernhard has no apologies.

“We were fighting an evil—organized fixing of college games,” Bernhard says. “We did our job. We got the big people like Molinas. There were 13 arrests and 13 convictions, and we stopped crooked games. The men I worked with are honorable. If our methods got a kid to make a false confession, I’m sorry, but we had a job to do. And remember, everything we did was legal at that time.

“We didn’t inform them of their rights,” Bernhard points out. “We didn’t offer them counsel. Hawkins asked if he could call his mother from the hotel. I said I’d prefer he didn’t. Actually, we weren’t going to let anybody make phone calls until we were all finished questioning them.”

Throughout the interrogations, the players were reminded that jail awaited them if they lied before the grand jury. “We hammered perjury of them,” says Bernhard. “’Lie, and it’s one to five years,’ we’d say. And this Hawkins kid was scared. In fact, of the over 150 kids we had in there, he was probably the most frightened and least intelligent. When I picked him up in Iowa, I thought he was trying to con me. I thought, ‘Nobody can be this dumb.’”

The pressure had begun the day Connie was returned to New York. That night in the Prince George Hotel, he was put in a room with players Art Hicks and Hank Gunter. This pair already had been held five weeks, had admitted fixing games, and had begun cooperating with the DA. “You better tell them everything you know,” Hicks warned Connie, who was trying to figure out what a point spread was. “Don’t let them find out for themselves. They don’t miss a trick. You better talk.”

Hawkins recalls little of the actual interrogation. But Wilky Gilmore has vivid memories. “Once Andreoli [Assistant DA Peter Andreoli, who was in charge of the case] questioned me, and every five minutes a detective would say, ‘All right, he’s lying, let’s lock him up as a material witness.’”

Hawkins wasn’t the only player who changed his story. “I told them what they wanted,” said one player who probably was involved. “In the grand jury, I said anything that came into my head, things that never could have happened. Later, I was told that if I went to see Hacken with a hidden microphone, they’d write a letter exonerating me. I cooperated. But when I went to get the letter, Andreoli said they couldn’t put it in writing.”

In such surroundings, Connie—without a lawyer—didn’t have a chance. “They kept saying, I’d go to jail if I lied,” he says. “Then they’d say they thought I was lying. So, I thought I’d go to jail if I didn’t tell a different story. And I knew what they wanted me to say. They were always saying, ‘Didn’t you get $500 for introducing players?’ I just decided I’d never get out if I kept telling them the truth.”

The saddest part is that Connie thought his incriminating story would never be made public. From the beginning, immunity from prosecution had been explained to him. But eight years later, he still doesn’t understand it. “I think it means that whatever you say won’t be held against you, and you will be cleared,” he says hesitantly. “I thought what I said to the detectives was a secret.”

He appeared before the grand jury on May 10, 1961. “I went into Andreoli’s office, and he read me the questions,” he recalls. “I don’t know if we went over answers, but I remember it was frightening the way he yelled at me about perjury again. My head was swimming. In the grand jury, I remember being sworn in, and all the people looking down at me. I couldn’t see no faces. I don’t have no idea what I said. I was so scared I could’ve admitted killing Cock Robin. The next thing I knew I was back at school and realizing it wasn’t a secret—and then I was leaving school.”

Hawkins was a tiny piece of evidence. Why did the DA’s office grill him so rigorously? Because it wasn’t easy to tell which players were lying. And because Assistant DA Andreoli hoped to build such an overwhelming indictment against Hacken that Joey would testify against Molinas in exchange for a lighter sentence or a stroll in the sun.

Everything was thrown into the entitlement—including the $200 Molinas, not Hacken, loaned Hawkins. But Hacken pleaded guilty to two counts of bribery—neither involving Hawkins—and went to jail without implicating anyone. And Hawkins was not among the 22 players cited when Molinas was indicted one year later. For Connie, though, the damage had been done.

Connie returned to Brooklyn in the late spring of 1961, the stigma of the scandal surrounding him. “Nobody would have anything to do with Hawk,” says his friend Jackie Jackson, who now plays with the Globetrotters. “His own people looked down on him. They’d say, ‘What you gonna do now, you fool?’ He didn’t know nuthin’ but basketball. He had no income. He’d just go to the courts and shoot around. In the tournaments, nobody would play against him till Wilt Chamberlain finally did. Man, one night when the other team found out who Hawk was, they walked off the court. He was really down. It’s a wonder he didn’t turn to dope, like half the neighborhood.”

But in the fall of 1961, the American Basketball League started, and Connie joined the Pittsburgh Rens. “When he signed the contract in his mother’s apartment, a roach crawled over it,” remembers Leonard Litman, president of the team. That night, Littman took Hawkins to the Park-Sheraton Hotel. As Litman was registering, he noticed that Connie was watching over his shoulder. Litman signed his name, and then Connie, who had never registered in a hotel before, also signed “Lennie Litman.”

Even as a 19-year-old with no college varsity experience, Hawkins became the ABL’s superstar. Other ABL players like Larry Siegfried and Bill Bridges and Dick Barnett later went on to star in the NBA, but Connie was leading scorer and MVP. He had no agent, however, and his business sense was less than acute. He played for $6,500 is for a season [today, $67,000]—then signed for the same $6,500 the next year. It didn’t matter. The ABL folded early in its second season.

“When Connie came home from Pittsburgh, he was cryin’ again, just like after Iowa,” Jackie Jackson remembers. “He said, ‘Jack, everything I touch turns rotten. What can I do?’”

What he did was join the Globetrotters for four years. It was good for him. “I learned to travel. I learned to speak a little of some foreign languages. I got more confidence in myself, and I did a lot of growing up,” Connie says. He also learned to handle the ball with the Globetrotter flair that has become his trademark.

Hawkins quit the Trotters in 1966 when he tired of touring endlessly in Europe for $125 a week. He returned to no job. “I’d sleep late, then get my ball and go to the schoolyard,” he says. “I had a wife and child, and I didn’t know how to make a living. That was the worst time of my life.”

But the ABA emerged in 1967, and Connie joined the Pittsburgh Pipers, who moved this past season to Bloomington, Minn. and will move next season to Jersey City. A lawyer, David Litman, a brother of the Rens’ former owner, was advising Connie when he signed his first Piper contract, and he got $15,000. He led the Pipers to the championship, led the league in scoring, and was again MVP.

This season, he played without a contract, so he could become a free agent in June—just in case he wins his suit against the NBA. The Pipers still paid him $30,000, which is a nice piece of change, yet small compared to Wilt Chamberlain’s $250,000 annual salary in the NBA, or even Oscar Robertson’s $100,000.

Why does the NBA keep Hawkins in exile? It knows how valuable Hawkins could be to one of its weak franchises. But the league has an understandable paranoia about gambling. One pro scandal could kill the NBA. So, the league has strict bylaws permanently barring any player who has ever been associated with “known gamblers.”

But in seeking to maintain moral purity, the league does not always concern itself with such things as due process and the presumption of innocence. In November 1963, Hawkins’ lawyer wrote to remind the NBA that Connie was eligible for the upcoming player draft. But no NBA team drafted Hawkins in 1964. The following season, when the New York Knicks, St. Louis Hawks, and Los Angeles Lakers asked for permission to negotiate with Connie, NBA commissioner Walter Kennedy turned them down. Finally, in May 1966, the league’s Board of Governors officially barred Connie, pending an investigation by Kennedy.

Up to this point, the NBA had made scant effort to determine the validity of the charges against Hawkins. In February 1966, it hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to investigate, but got no new information. Earlier, Kennedy had met with Assistant DA Andreoli. Recently, in an examination before trial of Connie’s civil suit, Kennedy said under oath that Andreoli showed him the Hacken indictment and told him that Hogan’s labeling of Connie as an “intermediary” was accurate, that “the allegations contained in the indictment are basically so . . . ,” that Connie knew Molinas and Hacken well, and that Hawkins did attempt introductions for the purpose of fixing games.

On the other hand, also testifying under oath, Andreoli says he did no more than show Kennedy the indictment.

In any event, the NBA did not ask the DA’s office which players Connie was supposed to have approached and did not question any other detectives on the case until after Hawkins had filed his suit. The league still has not questioned Hacken or Molinas.

Kennedy finally responded to Hawkins’ lawyers in May 1966, but did not inform them that Connie has been officially barred pending investigation. Instead, the NBA commissioner simply invited Hawkins and Litman to his office, where Connie was to be questioned by Kennedy and the NBA’s attorney and then permitted to make any statement he wished. Then Kennedy would “continue” his investigation and “issue a ruling.”

Litman agreed to a hearing, but insisted it be “fair and impartial.” He offered two proposals: (1) that the league inform him of the specific charges against Hawkins, give him time to investigate, and then hold the hearing; or (2) that the NBA allow him to cross-examine Connie’s accusers, then let him investigate and present a defense.

Kennedy rejected both proposals. Instead, the commissioner said he was proceeding with his own investigation, and asked Hawkins to answer, in writing, and under oath, four questions pertaining to counts in the Hacken indictment. Litman—noting that Connie still had not been informed of the specific charges, or told who his accusers were, or informed on what basis he would be charged—advised Connie not to answer the questions.

For all of this, the fact is that the NBA has been inconsistent in its attitude toward “tainted” players. Kennedy cited Hacken’s indictment in barring Connie, but now he admits that until a few months ago, he never checked the document to see if it also mentioned any NBA players. In fact, the first player named in the entitlement is Fred Crawford of the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers. Hacken is charged with offering Crawford, then at St. Bonaventure University, a $1,000 bribe, which the DA says Crawford didn’t report.

Kennedy says he didn’t know Crawford was in the indictment when he first approved the player’s NBA contract in 1967. But, says the commissioner, it wouldn’t have mattered, he still would have held no hearing or investigation. Why? Because St. Bonaventure—which never held a hearing—allowed Crawford to continue playing, after he spent one year in the hospital with tuberculosis.

Meanwhile, Hawkins waits, outplaying the NBA superstars in the playgrounds, where he also worked as a supervisor last summer. He will have the same job this summer. His post-basketball earning potential is minimal. The prime of his career is approaching. And he doesn’t know if the ABA will last another year. But somehow Hawkins has resisted bitterness. “There’s a lot of disappointment,” he says, “a lot of years wasted. Now, I just want to prove what kind of player I am in the NBA and clear my name. That’s more important than the money in the suit. I want people to know I’m an honest player.”

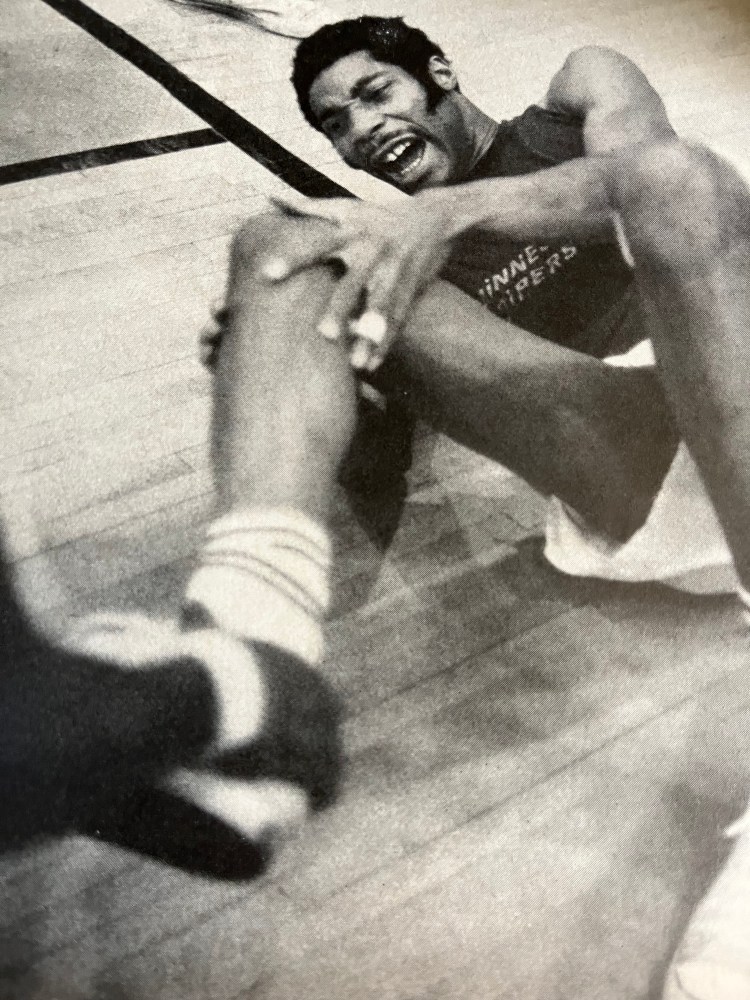

In the middle of this past season, Hawkins tore cartilage in his right knee. He was sidelined for two months. But for one frightening evening, he wondered if he would ever play again. He lay in the hospital, his good leg dangling over the end of the bed, his injured leg in traction. “I don’t know what I’d do if I couldn’t play no more basketball,” he said quietly. “I think that would just be the end of Connie Hawkins. There wouldn’t be no more me.”

When he was hurt, the Pipers had been in first place in their division; without Hawkins, they finished fourth. By then, Connie’s leg had healed enough for him to limp through the playoffs. Before that, however, he visited New York and went to watch the Knicks at the new Madison Square Garden. It has been nine years since he played in the old one. “I’ll never forget it,” Connie said, gazing around the shiny new lobby. “Playing for the city championship in front of 18,000 people. It was Cloud Nine. The noise, the fans, and the smoke—it kind of hung over the court, but never touched it, just hanging there like a halo.”

The New York fans recognized him immediately. “Connie Hawkins,” they yelled. “How ya doin’, Hawk?” A husky young man in a rumpled blue suit tugged at Connie’s arm. “You’re the greatest in the world,” he said. “Been watching you since Boys High. How’s Roger Brown? Where’s Tony Jackson playing?”

“You a real New Yorker, man,” Connie grinned.

“Listen,” said the fan excitedly. “I don’t care what you guys did in the past. The ABA ought to put a franchise in Brooklyn. They could have Roger Brown and Doug. Moe and Tony Jackson and you, all on the same team.”

A sad smile played around Connie’s mouth, and he looked down at the man for what seemed like a long time. Then he sighed, “Yeah, they could call us The Fixers.”

Thank you so much for printing this. I had been a Connie fan dating back to his first season in the NBA–can’t call it a rookie season, of course. I had picked up a copy of Foul when I was in high school a few years later and was riveted. In a very strange turn I met Dave Wolf in the late 80s. That’s when he had reinvented himself as a boxing manager, first with Ray Mancini and later, when I talked to him, with Donny Lalonde, a very limited (practically one-armed) fighter who somehow managed to win the light-heavy crown and parlay into a big payday vs Sugar Ray Leonard. I interview Lalonde at Wolf’s place in Manhattan and told him how much Foul had meant to me and he had a bit of a faraway look, like it was another lifetime before and work that he loved that he gave up (or had to give up). Not an artist when it came to turn of phrase but the reporting in the Life story and in Foul is tremendous. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Thanks for the memories, I met the Late Hawk in NYC in the 60’s, I was in the city visiting on leave from the USAF, saw him @ schoolyard hooping, hell of a player !!!

LikeLike