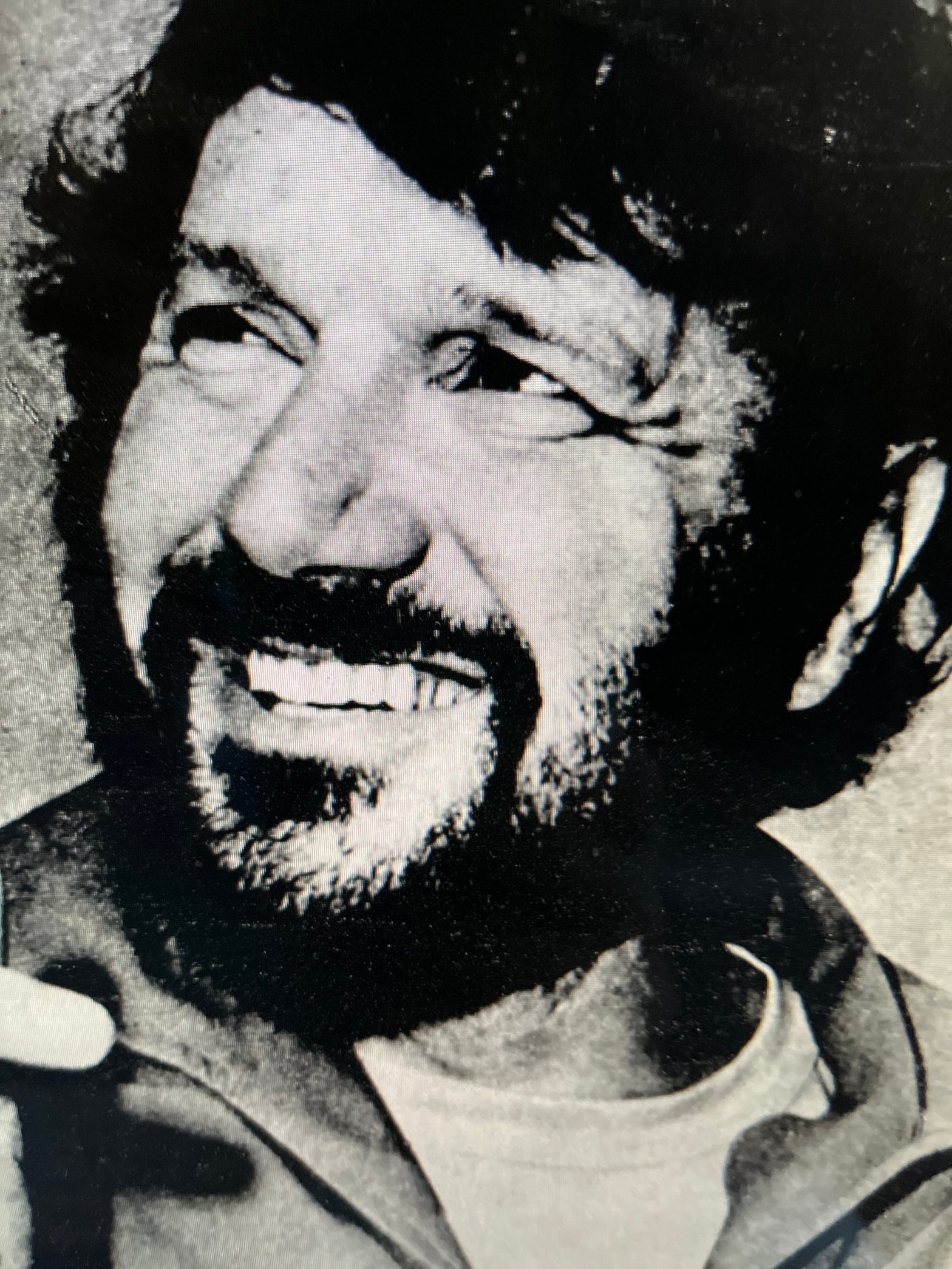

[Franklin Mieuli was the pioneering NBA owner of the Warriors in the San Francisco Bay Area (1962-1986). He was also truly one of a kind. In this article, journalist Murray Olderman tries to explain the Phantom, the Man with the Golden Touch, The Strange One. To truly capture the enigmatic Mieuli, Olderman probably would have needed 5,000 words or more. But Olderman does an admirable job in this humorous piece which ran in the San Francisco Examiner on April 23, 1973. Enjoy!]

****

It took 98 days to get Franklin Mieuli to sit down and explain the meaning of professional basketball in his frenetic life.

It all started one Monday night in late 1972 when Franklin came up to my place to meet Pete Rozelle and watch the Danderoo, Ho’ard, and Giffer Show on ABC. While the teams on the screen huddled, Franklin dove into the cheese and salami. He then expounded on being Big Daddy to a bunch of human giraffes and told how he had paid one Mahdi Abdul-Rahman more than $100,000 to play for his team, the Golden State Warriors, this season. After that he vanished into the night, leaving behind his beret.

Franklin has this habit of disappearing. The next couple of months, there were only fleeting glimpse of him—once in his aerie high in the Oakland Coliseum, where he materializes at odd times to watch the Warriors, another time in the backroom at Perry’s. There were reports he was also seen in his backyard in San Jose, pulling up weeds.

“I’ll see you after the holidays,” he kept saying. “For sure.”

Even faithful Anita, who fields all messages for Franklin, didn’t know where he was. And then he flew off to Chicago for the National Basketball Association All-Star game, due back on Wednesday. In Chicago, Ken Macker, the public relations guy who linked up with Franklin this year to help straighten out the Warriors’ image, planned to go to dinner with him. He saw Mieuli going through the revolving door and saw him no more. Franklin had kept on going to New York.

There, Ned Irish, the austere boss of Madison Square Garden, asked Franklin to join him at the posh Garden club when he learned Mieuli was in town to negotiate the contract which would take the NBA out of the lens clutch of ABC and into the big eye of CBS. So, Franklin showed up, and the man guarding the door took one look at this guy with the scraggly facial hair and the torn Levi’s and the wild shirt and said, “Get lost.” Franklin smiled his little boy smile and disappeared. Irish was furious. At the doorman.

Years ago, when Franklin used to travel with the baseball Giants, whose games he produced on radio and television, he’d go out at night with Chub Feeney, Lon Simmons, and the late Russ Hodges. They’d all be holding a drink around the piano bar, and there’d be another on the way, and suddenly the other three would see an empty glass. No Franklin. “It’s too much trouble,” he explained once, “to say good night.” Feeney named him The Phantom.

****

On a rainy morning, 98 days after initial contact, the phone rang, and Anita said, “Franklin will be in his office tomorrow. Any time you want him.”

And he was there.

You have now met Franklin Mieuli, who owns 96 percent of the Golden State Warriors of the NBA, 10 percent of the San Francisco 49ers of the NFL, and a chunk of the San Francisco Giants of the National League. “Emotionally and financially,” he says, “I am a three-letter man.”

He also has three children, two of them, married, and lives in a 12-room Victorian house renovated by his wife, Hilles. Home is 50 miles down the road in San Jose, which means 100 miles of driving every day, but, Franklin maintains, living there preserves his sanity.

If you could transfuse his Italian blood—Papa Giacomo, who’s now 88 years old, came over from Castellana, Italy—Franklin Mieuli would be leprechaun—with a little bit of Friar Tuck thrown in. He is burly and dressed mod-sloppy.

He is a staccato talker with a disarming smile, a guy you can like very easily. And his old cronies, like Rozelle, the football commissioner, and Macker, do. In pro basketball, where Franklin appears bizarre alongside slick, autocratic moguls, such as Jack Kent Cooke of Los Angeles and Sam Schulman of Seattle, those who don’t think he’s eccentric tend to think he’s crazy. He has from the start been a dogged opponent of merger between the NBA and the American Basketball Association, whose rivalry has skyrocketed salaries.

It would be too easy to toss off Franklin, because of his dress and his casual lifestyle, as a buffoon. He is not. He is a smart guy who has hung on in professional basketball, because he is convinced that it, like everything else he has touched in his life, will ultimately make him a bundle.

The Warriors, transplanted to San Francisco from Philadelphia in 1962, have staggered through 11 waif-like years in and around The City. Now lodged in Oakland, they are euphemistically called Golden State. They were first controlled by a couple of men from Diners Club who were staggered by a loss of $225,000 the first year of operation. Franklin, who produced the game broadcast and had picked up 7 percent of the club when it moved West, arranged to buy them out. By the 1966-67 season, with Rick Barry the scoring star of the NBA, the Warriors were the third best draw in basketball, behind Los Angeles in New York. Then Barry jumped to the newly created ABA, and the hard times came to Franklin Mieuli. Last season, the Warriors were dead last in NBA attendance.

This year, Barry, the enfant terrible, returned with a contract for $218,000 a year. The player payroll of the Warriors climbed to $1.2 million. Season ticket prices were raised. The team, artistically no better than a year ago, when it finished second in the Western Division of the NBA, attracted slightly over 6,000 customers a game. To break even for the 41 home dates, they would have had to average 6,500 fans. Franklin figures to lose about $250,000, or the equivalent of Nate Thurmond’s salary, this year. It’s a loss he can absorb comfortably, for now, because of his profitable share of the 49ers, worth about $1.8 million, and his thriving television and radio production business, which handles almost every sports event coming out of the Bay Area. (The Warriors, too, on the open market might be worth as much as $8 million.)

“I am robbing Peter,” said Franklin, “to pay Paul.”

He was sitting in his office, which has a brick wall on one side and no window. Its motif is abstract clutter. Somehow it reflects Franklin. He has a fetish for hands. He uses them profusely when he talks. He has pictures of them on the walls. He has a wooden chair carved in the shape of a cupped hand. He has hands cast in bronze.

“The whole strange world of Franklin Mieuli—professional division—is housed at 556 Golden Gate,” he said. Recording studios and tape duplicating machines, for his other business are right below his office, in the basement. “Lower level, please,” he implored.

One reason advanced for the struggles of the Warriors is that the egomania of Franklin Mieuli has dwarfed his own team. “There was a time,” he nodded, “and I did these things with malice aforethought, I was ubiquitous.

“I was all over the place and had things to say and reasons for saying them. I felt the Warriors needed something. If I could sell them the Warriors by peddling Franklin Mieuli, then I felt it was my function. Well, you remember, how boxing was. It got overexposed. And I think Franklin got overexposed. When guys like Prescott Sullivan, whom I respect tremendously, could say, “Holy smoke, there was a time I couldn’t spell M-i-e-u-l-I, and now I’m a little sick of picking up the pages . . .”—when egomania became a contestant of the image of the team—I realized I had overplayed my hand. The remedy was to just disappear.

“Up until now, I’ve been the Man with the golden touch,” Franklin continued. “I went to work for the Burgermeister Brewery after the war. It was producing 350,000 barrels of beer a year, a very small San Francisco brewery. When I left seven years later, it was producing almost four million barrels. I went to work as a $250-a-month advertising jockey and ended up head of the department. Through that I met Tony Morabito. He offered me 10 percent of the 49ers for $60,000, and when I tried to raise it, people thought I was nuts, including my father. I said, ‘Dad, I’ll share it with you.’

He said, ‘Franklin, if it’s as good as you think it is, it’ll screw up my tax bracket. If it’s as bad as I think it is, no thanks.’

“I left the brewery and opened a radio and TV production business. Who knew what TV was going to be? The Giants come out and I’m producing the broadcast, and Mrs. Joan Payson, who bought the Mets, sells me her shares, or a chunk of them. Then the Warriors. One success after another. Everything came quick and easy.

“But since 1967, it’s been a struggle. First, I lose Rick Barry, and I spend all those years trying to get him back. It was a kick in the solar plexus to all our fans. I blame myself for not being on top of the Rick Barry-Bill Sharman-Bruce Hale triple entente. I’ve agonized over this so many times.”

Sharman, who also jumped to the ABA, was the Warriors’ coach then. Hale was Barry’s father-in-law and organizer of the Oakland ABA team, which lured Rick across the bay. Rick came to Mieuli after the big 1966-67 season and said, “It should’ve been the best year of my life, and it was agony.” Franklin hadn’t recognized his discontent. When the losses piled up on him—a reported $900,000 in 1970—and his partners started to bail out, pro basketball in the Bay Area was jeopardized.

“Closest we came to leaving,” mused Mieuli, “was the possibility of playing half the schedule in San Diego two years ago. The people down there asked me, ‘If we outdraw San Francisco, would we get the club?’ And I said, ‘No. If the Warriors stay where they are, drawing 4,000 a game, and you double their draw, that might cause me to sell the club to someone down there.’

“But I have no intention of moving. I have an emotional commitment to the Bay Area. I’m sustained by 1966-67. That was no fluke.”

Franklin Mieuli is, foremost, a fan. He runs his team that way. He claims he doesn’t meddle. Sure, he brought in Rahman, formerly Walt Hazzard, when it was obvious the Warriors needed a playmaker. Bob Feerick, the general manager, and Alvin Attles, the coach, were dismayed. “Jesus Christ,” they said to Franklin, “it’s over $100,000, and Buffalo’s letting him go. How can he help us?”

“Then,” recalled Franklin, “Alvin said, ‘I don’t have to play him, do I?’ And I said, ‘Nope,’” Rahman didn’t play. Mieuli continued, “Ben Kerner and Bob Short (former NBA owners) used to tell me, ‘You leave a team to your goddamn manager, and he’ll run your salaries up. Leave it to the coach, and he’ll trade off your best player because he doesn’t like the way he parts his hair.’

“Al Davis (of the football Raiders) tells me, ‘The trouble with you is you got a love club over there. Everybody loves everybody. The area, the teammates, the coach. I watch the Lakers come off and they do something wrong, and they’re afraid to face Sharman.’

“They’re probably right, but I can’t run it any other way. I really love serenity. But my mind’s up there. I’m totally involved with the basketball. I agonized before moving over to Oakland full-time. In 1962, the city fathers told me, ‘Don’t worry, Franklin, my boy, in three years, we’ll have a place for you.’ And they still haven’t got it.

“There was just no way I could have survived here. The jury’s still out as to whether I can survive over there. This year’s not really a good year to make a judgment on. We’ve all made errors—myself, the players, coaches, even the media. With the addition of Rick Barry, were going to have a super team. Well, we’ve got a good team; we don’t have a great team. The Lakers average 15,000 people a game. We’re drawing 6,000. If we can get up to 10 or 12,000, we can afford basketball. Right now, we can’t. Whose fault is that? It is my fault.

“Because for the average fan who needs a little arousing, we’re a second-place club with Rick Barry, and we are in second-place club without Rick Barry.”

And that still leaves a lot of bills to be paid.

“We’re up this year,” said Franklin hopefully. “We’re double dollar-wise. My attorney says, ‘Big deal. Two times zero is zero!”