[Bill Mokray joined the Boston Garden in August 1944 as head of basketball operations. That translated to arranging college basketball doubleheaders. Two years and several smashing doubleheaders later, Mokray added the title of publicity director for one of the Garden’s new residents, the Boston Celtics. And that’s where Mokray remained until October 1967 when Celtics’ owner Marvin Kratter pulled him aside one day and said, “We’re letting you go. We’re bringing in a younger man.”

Mokray walked away from Boston Garden as one of the game’s most-innovative statisticians and a walking-talking NBA encyclopedia. (The talking part reportedly irritated Red Auerbach and might have entered into his dismissal.) As evidence of his encyclopedic basketball brain, Mokray published an annual paperback during the early 1960s that profiled the game’s top collegiate and pro stars. The writing can be too fluffy and flattering in places, but Mokray clearly knew his stuff. You’ll see that on display here in his profile of Tom Gola, then with the Philadelphia Warriors. You can find the profile in Mokray’s Basketball Stars of 1962.]

****

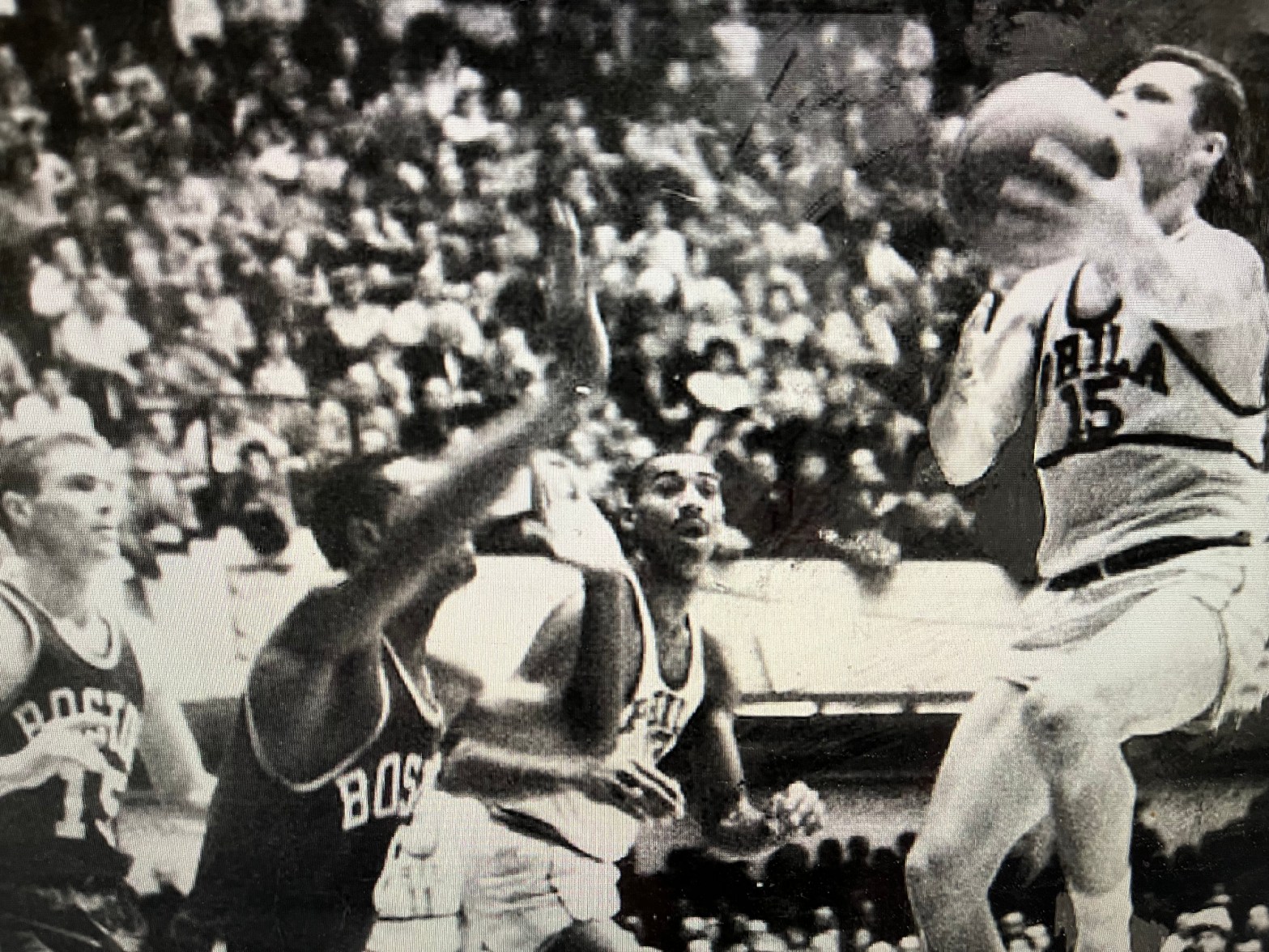

Basketball buffs will always have a field day, naming the best all-time player. Some may rank high because of their unerring shooting, others for their playmaking, rebounding, or floor generalship. But when it comes to general all-around excellence, poise, and clutch performances, then Tom Gola of the Philadelphia Warriors must be regarded as an all-time All-American.

Harry Litwack, Temple’s cigar-smoking coach who has seen his share of stars in the pro and college ranks, is of the opinion that “Gola is the only fellow I ever saw who is a distinct threat and playmaker without the ball.”

“Gola is a super All-American, the perfect basketball player,” is the opinion of Howie Dallmar, one of the few, if not the only fellow, who won All-American honors at two different colleges (Stanford and Penn) and then was an All-NBA choice while performing for the Philadelphia Warriors. “Gola is two Hank Luisettis wrapped in one, and I ought to know because I played with Hank,” added Dallmar.

It was not surprising, then, to note that when a national sports magazine a half-dozen years ago asked a staff of veteran college coaches and writers to name an all-time All-America team, the top five consisted of Chuck Hyatt, Luisetti, George Mikan, Bob Cousy, and Gola.

It is fitting to refresh one’s mind on LaSalle’s basketball record for the four years that Tom played varsity ball, 1952 to 1955. In his freshman year, the Explorers won 25 of 32 games and copped the National Invitational Tournament (NIT). The following winter, a 25-3 campaign, they were upset by St. John’s, 75-74, in defense of that NIT title. The year after, they became the NCAA champions with a 26-4 record, and undoubtedly the Explorers would have repeated in 1955 except that it was their misfortune that that was the year a fellow by the name of Bill Russell made San Francisco invincible.

What makes this feat more remarkable is that LaSalle was not blessed with much talent. In the very words of the ubiquitous LaSalle coach Ken Loeffler, “All we have is Gola and four students.”

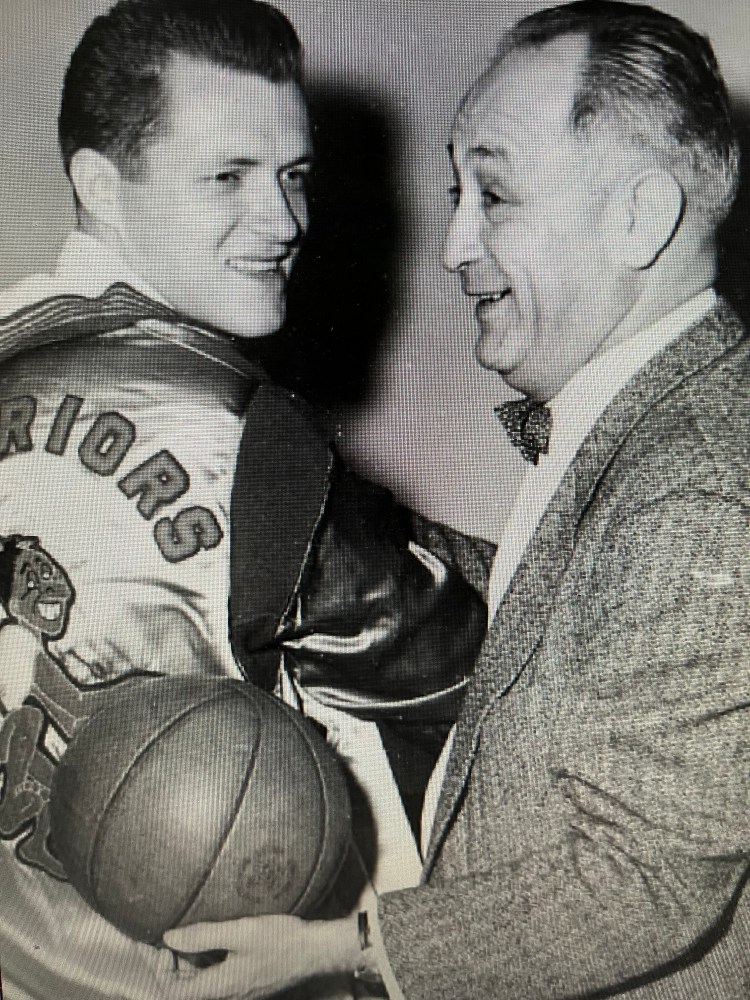

Tom’s true greatness may be measured by other means. In the very season before he joined the Philadelphia Warriors, Eddie Gottlieb’s club finished last in the NBA’s Eastern Division race with a 33-39 mark. The next season, Tom joined the club. It not only led the entire league with a 45–27 record but copped the world title. And the only newcomer was Tom Gola!

The quiet, crewcut with a Johnny Murphy type of jaw and brown eyes is one of the most inconspicuous fellows on the floor. He is ready to sacrifice personal glory for team triumph. He has the speed of a small man. There isn’t anything he can’t do out there, and he doesn’t have to be told.

Tom’s all-around game goes back to when he first started playing at the age of 13 at the Incarnation Parochial School in North Philadelphia. He gives no small credit to his first coach, Lefty Huber. A bit taller than his classmates, young Thomas excelled as a pivotman until Lefty, in his usual fatherly manner, took him aside one afternoon and asked him point blank what would he do when he ran up against opponents his size or taller?

“You’re heading no place,” warned Huber, who would talk as tough as any army sergeant and make the kids love him even more. “If you have hopes to get ahead in this game, Tommy, you’ll have to learn to dribble, fake, run, pass, shoot from the outside.”

How well the youngster heeded such advice is borne out by succeeding seasons. LaSalle High and Tom were outstanding for four seasons. When he graduated in 1951, he had a grand total of 2,222 points. No fewer than 64 colleges made offers over and under the table. However, a home-loving boy, he preferred LaSalle College.

Winning top honors has been a regular habit with Tom. In his four seasons with the Explorers, he had successive totals of 504, 517, 690, and 750 points in 118 games, for a 20.9-point game average. He won MVP honors in the 1953 NIT and 1954 NCAA tournaments. The New York City writers named him for the Gold Star Award (best visiting player) in 1953 and 1955, the first time this was won twice by the same fellow. He also won MVP honors in the Holiday Festival.

In his junior year, Tom was picked for three prizes by the Philadelphia writers—the annual Palumbo trophy as that district’s top scorer, the MVP in the Quaker City area, and the Robert Geasy Award as the nation’s number one for that season. By a strange coincidence, he repeated in all three categories the following winter. Instead of duplicating the trophies, the scribes simply asked him if he’d return them, so that they could add his name for another year. The writers understood Tom contemplated marriage, so they presented him instead with an impressive silver service set . . .

But back to the writers’ dinner, which had several strange twists. Among those to be honored, was Donald Moore, Duquesne coach. He could not make it, and an 11th-hour substitute was one of his players, Dick Ricketts, who appeared in a sweater. Before Dick fulfilled his duties, he had to go off-stage to borrow Gola’s coat and reverse the procedure when Tom took his bows, so the two were never at the head table at the same time. A surprise guest was Tom’s dad, Isadore, a Philadelphia bluecoat, who proved quite a hit through a mixture of shyness and pride in his illustrious son.

Off the court, Thomas is placid. He speaks softly and conveys a certain sincerity in any thought expressed. He majored in accounting. In his undergraduate days, he used to relax by playing the harmonica or listening to jazz music. During high school, he high jumped and ran the quarter mile, but Loeffler took care of that.

Tom’s entry into NBA ball wasn’t auspicious. A holdout, he did not join the Warriors until three days before the preseason drills got underway. Then, in the second game, he broke his right hand, forcing him to miss the first four games of the regular schedule. What made the task all the more difficult was that he had to play the backcourt, which was new to him, since the Warriors had a powerful frontline of Paul Arizin, Joe Graboski, and Neil Johnston. The three averaged 60 points between them, which was quite high for those days. Tom had to alter his style under trying circumstances.

For a number of seasons, fans and writers have argued whether Tom would serve the Philadelphia cause better if he played up front. When questioned on that point, Tom’s only answer is, “Gottlieb didn’t hire me to be a high scorer. I just try to do the job expected of me. Hogging points is not basketball.”

In his first season with the team, the club held a Gola Night. The players prearranged that Tom was to score the first basket. After several screens and feints, the Warriors finally shook Tom loose, and he scored. The place went wild. “You know,” Tom later said, “it was the first time they set me up for a basket since I joined the club!”

That the hometown boy is a local idol goes without question. When he wasn’t picked for the 1960 All-Star game, a big howl went up. After all, he had had a banner season, 15 points a game, 19th top scorer in the league. Not bad for a backcourt man. As luck would have it, Arizin caught the grippe the day before the game, and Tom was named as his replacement. The fans’ faith in Tom was justified since he played such a fine game that when the writers held their poll for MVP honors, Wilt Chamberlain got 18 ½ votes and Tom came in second with 6 ½ votes.

A keen student of the game, the handsome fellow plays his best when the going is the roughest. The first time he faced Oscar Robertson, he held him to 15 points. Tom later explained that he had seen the Big O on TV for one quarter. “I immediately detected that he lined up his shots off the dribble. Where Bob Cousy would dribble behind a pick and stay there, forcing you to make a move, Oscar went behind the pick and came right out on the other side. So, Guy [Rodgers] and I prearranged a switch, and Oscar found me, a taller fellow, waiting for him.”

The best performers in all sports have their bad nights, and Tom is no exception. In the 1958 playoffs against Boston, Tom missed all 13 shots from the floor. Few were aware that he had a cyst on his chest, and he played with a brace. Nevertheless, he was so angry with himself when he came home that he made a vow to his wife that in the next game he would shoot at every opportunity. He made good on his promise. He hit on 11 of his 22 tries, nine of his 12 free throws, got 11 rebounds, and scored 31 points.

Few appreciate the way he harasses opponents. After a St. Louis game a year ago, Bob Pettit said, “That Gola steals eight to 10 balls against us in every game. That adds up to about 10 extra points in any game. All our guards do is talk about him.”

His LaSalle teammates still talk a game wherein he was injured. When the manager came into the dressing room to check on him, he found Tom with a pencil in hand—undoubtedly writing a letter to his girlfriend! No, it wasn’t so. He actually was doing his homework while the game was being completed, and with his left arm, he held an ice pack on his sore neck. Stories such as the above show why Tom Gola is as much of an All-American off the court as in a uniform.