[No introduction needed for John Stockton. In this article from the February 1989 issue of Hoop Magazine, Stockton is a 26-year-old NBA star is on the rise in his fifth season in the Salt Palace. Recording Stockton’s rise is the Deseret News’ Kurt Kragthorpe. In 1990, Krapthorpe moved over to the rival Salt Lake Tribune, where he served as a sports editor, columnist, and beat writer until his retirement in 2020. Kraghorpe was an outstanding reporter and columnist.]

****

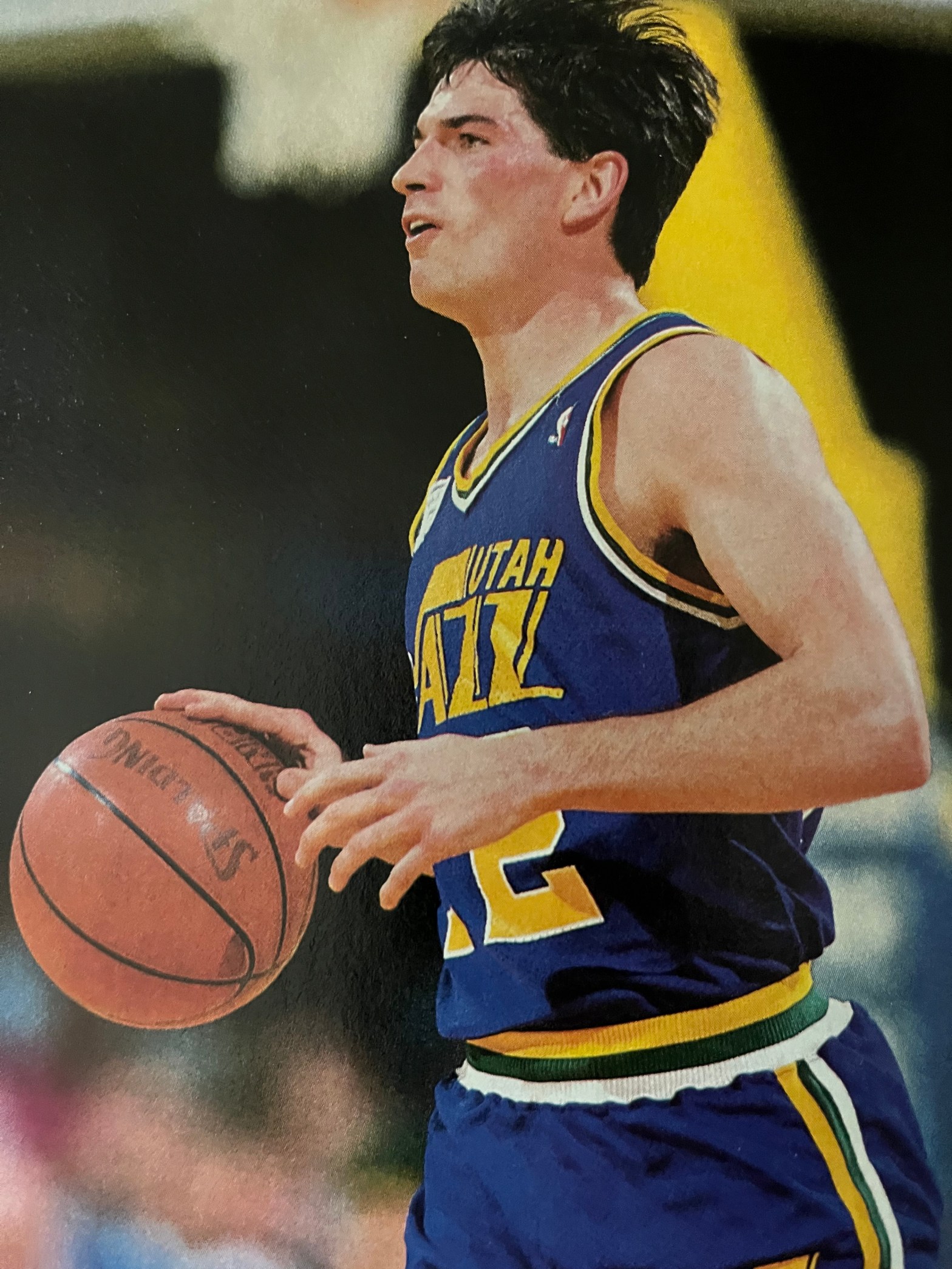

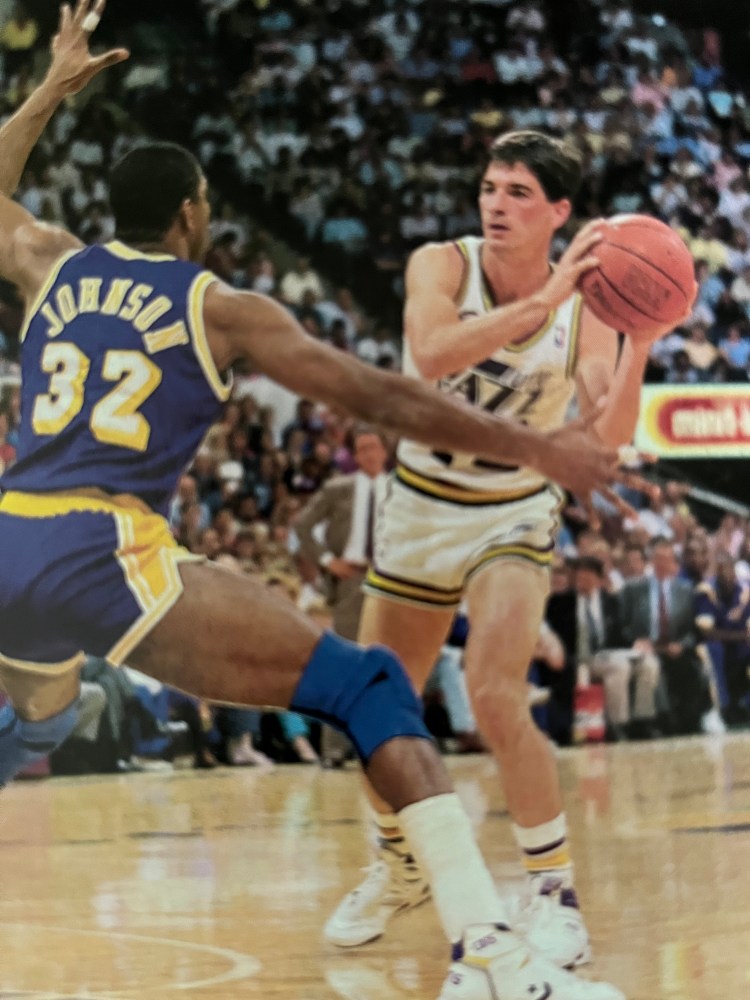

All of a sudden, we find Utah Jazz guard John Stockton breaking an NBA season assists record, making commercials, being voted the Jazz MVP by his teammates, and being talked about in the same sentence with players like Isiah Thomas and Magic Johnson.

You mean the John Stockton who came from Gonzaga University, still insists on fixing up his own house, and never liked to shoot?

Same guy.

Now in his fifth pro season, Stockton is once again doing all the things that brought him attention last season when he helped the Jazz to their best record ever, 47-35, and scared the eventual champion Lakers like crazy in the Western Conference playoffs. Stockton turned heads by breaking Thomas’ NBA season assists record with 1,128 last year, but he’d already surprised even some local followers by taking over the Jazz’ starting point guard job from veteran Rickey Green.

Did anybody really see this coming?

We take you back to the summer of 1986, when Jazz president David Checketts is discussing a new contract with Stockton’s agent. Stockton was coming off a second NBA season during which he was a starter until mid-January, when Green took over again.

And Checketts was saying to Stockton, “He’s a backup . . . When Rickey Green gets old, is he the guy who’s going to fill in? I don’t know. He can’t shoot. He won’t shoot. He doesn’t have the size to shoot.”

Just look at Stockton now! Last season, he almost doubled his scoring average to 14.7 PPG, and his 57 percent shooting was fourth in the NBA—absolutely remarkable for a 6-feet-1 guard who either has to operate from outside or deal with the traffic inside.

“I wasn’t just negotiating,” Checketts says now of that 1986 conversation. “I really felt that way. I thought his size—and I really thought his personality—would be problems. I just didn’t think he was tough enough. I didn’t know how much he had in him, because he’s such a nice guy.”

They knew better in Spokane, Wash.

Both in high school and college, Stockton never really overwhelmed anybody until his senior year. His Gonzaga Prep coach, Terry Irwin, remembers being criticized for keeping Stockton, a 5-feet-5 sophomore, and only one senior on the varsity. Later, Gonzaga University coach Dan Fitzgerald had to convince an assistant to back off another player and give a scholarship to the hometown kid. “There weren’t a lot of guys beating down the door,” he says.

Stockton reached all-star level in the NBA the same way he did in Spokane—by playing relentlessly and by playing all the time. “He works hard at basketball—some guys don’t do that,” says Fitzgerald. “The one thing he really likes to do is play basketball.”

And now, the Jazz are discovering the Stockton that Spokane knows. “I don’t know how many times I find myself shaking my head and saying, ‘This guy has more guts than . . .’ He is a street fighter. He has the intensity and the competitiveness. He has all those things, and yet, he has great control,” marvels Checketts.

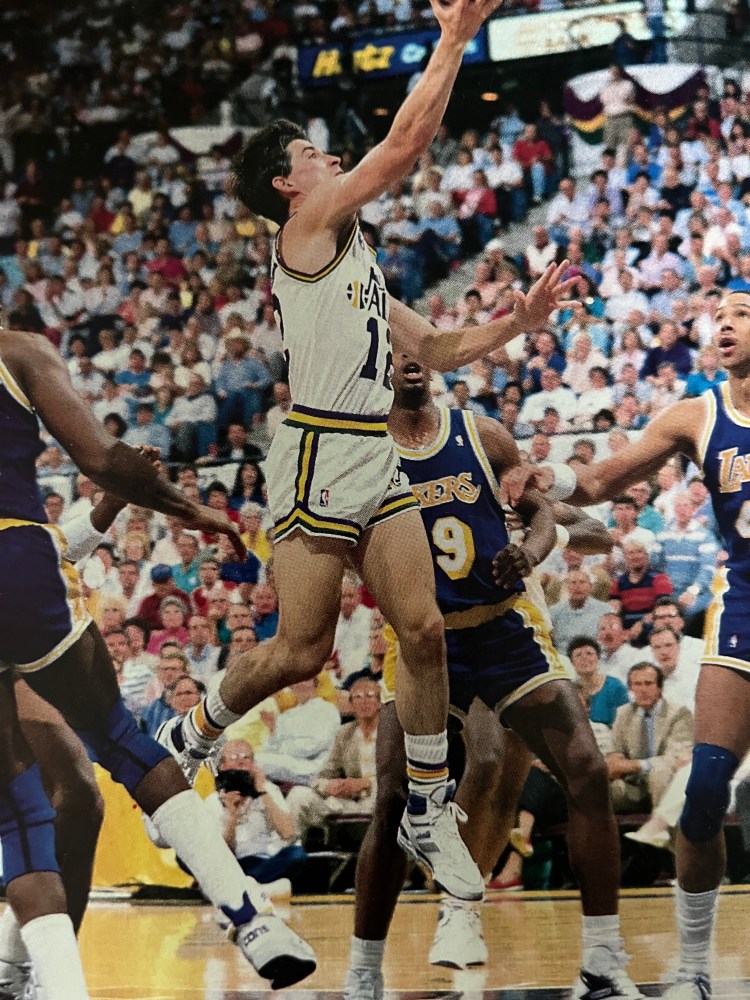

No doubt, Stockton and the Jazz are right for each other. Having fastbreak finishers like forwards Karl Malone and Thurl Bailey would be any point guard’s dream, and the Jazz are always looking to get the ball into Stockton’s hands, so they can run and run and run.

He’s comfortable in Utah, too. “It’s a college atmosphere, a great place to play,” he once said. “It may be what you’d call a small market, but I don’t think I’d be as happy playing anywhere else.”

As intensely as he competes, Stockton is really rather easy-going—part of a very intriguing personality package. Competitive? The word is tossed around a lot. But consider Stockton. He once played ping-pong against an unsuspecting reporter and won 21-1, then chewed himself out for losing one point.

In the summer, the Gonzaga gym is the gathering place for pickup games. Stockton holds court all day and usually wins. Players have complained to Fitzgerald that Stockton calls too many fouls and can’t keep score, but he tells them, “You argue with him.”

Reserved and almost difficult to interview when the subject is himself, he’s a ham in the right setting. When Stockton’s pass was intercepted in a high school practice, Irwin yelled, “Stockton, will you be creative?” From then on, every time Stockton would make a play, he’d smile mischievously and ask, “Coach, was that creative?” Later, knowing Irwin was present at a camp lecture, Stockton made a point of earnestly talking about the importance of being creative.

At a Jazz awards dinner last spring, guest speaker Bob Lanier praised Malone for a fine season, but advised him, “You ought to give a couple hundred thousand dollars to that little guy over there.” Stockton responded with a one-man standing ovation, which brought the house down.

In Spokane, he’s the same old Stock. With his NBA salary, he could have called the sprinkler-system people or the siding man, but that’s not the Stockton way. He rounded up his buddies to help on the home improvements, borrowing so many tools that boyhood friend George Lucas discovered Stockton knew his garage better than he did.

One summer afternoon, Fitzgerald drove past the house to find Stockton suspended from the roof, hammer in hand. “I bet the Jazz would have loved to see that,” he mused. Even last summer, Stockton rewarded himself with a week of 16-hour days spent remodeling the inside of the house immediately after returning to Spokane.

During Stockton’s three weeks of youth basketball camps in Spokane, his guest coaches were shocked to find him showing up at 6 AM every day for early-bird sessions and staying late every night, just as advertised.

Above all, Stockton just likes to blend in. “I don’t go home to parades,” he says. Undoubtedly, though, last summer was a little different. The town that produced Chicago Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg was suddenly more enthralled with Stockton than ever, with all kinds of requests for appearances.

“It’s been absolutely unbelievable,” his father and next-door neighbor, Jack ,reported last summer. “He’s been on the dead run ever since he got home. We try to answer every request, but it’s not in the cards.”

In Jack & Dan’s Tavern, the neighborhood bar that Jack Stockton and Dan Crowley took over in March 1962, 10 days before John was born, Stockton is treated the same as always. When his television soft drink commercial came out, the boys in the bar started calling him “Hollywood” to keep them humble. As if that was necessary.

Stockton never even looks at the sign in the tavern advertising his assists record. When he and his wife, Nada, brought their baby to Spokane to be baptized during the All-Star break last February, they walked underneath the bleachers to their seats at the Gonzaga game. John was genuinely embarrassed to be introduced at halftime. He stopped reading newspaper stories about himself in college, because he was afraid of having something affect his on-court thinking.

The funny thing about all this is that Stockton, the player, is totally confident. Even after Stockton lifted himself from a fifth-round draft choice to a first rounder with his play in postseason tournaments and the 1984 US Olympic Trials, Jazz followers were more than a little skeptical when he was drafted. Until last season, did anyone figure he could someday become an NBA all-star? Probably only Stock himself.

“He’s sure not humble,” says his father, smiling. “I know he’s very confident about his abilities. He’s had to be, because people have always raised their eyebrows.”

In a letter to Fitzgerald after his first day of Jazz training, camp, Stockton wrote, “They’re not that awesome . . . I definitely feel confident playing against them.”

An excellent student in college and the Jazz’ resident crossword puzzle expert, Stockton actually made a breakthrough last season when he decided to do less thinking and more reacting on the court. His decision-making, whether conscious or not, is almost flawless. “He’s a complete point guard,” says Malone. “He gets the ball in the right person’s hands.”

Of course, he’d say that, but you get the idea.

Besides making the right passes, Stockton added a new dimension to his game last season when he started to shoot more—and seemingly made everything. Stockton’s explanation was, “They’re not guarding me.” They are guarding him this season, but he’s still making all the plays.

And now that Green is in Charlotte, Stockton is playing even more minutes per game. How durable is he? Considering he played in every regular-season and playoff game through his first four years with the Jazz. In 1986-87, when he was still backing up Green, Stockton finished in the NBA’s top 10 in assists and steals while playing less than 23 minutes a game.

The critics claimed he could do those things only because he didn’t have to pace himself like other point guards. So much for that idea. Last season, averaging about 35 minutes, his statistics on a 48-minute projection were even higher as he became a complete offensive threat.

Stockton never showed signs of wearing down, much less complaining, when he played all 48 minutes in several games against the Lakers in last May’s seven-game series. “He must be in the best shape in the world,” said coach Frank Layden. Indeed, Stockton does have tremendous endurance—he frequently placed high in the famous Bloomsday Road Race in Spokane and now directs Fitzgerald’s conditioning program at Gonzaga every September.

Now that his personality is surfacing and he’s a full-time player, Stockton has all the makings of the Jazz’ leader for the next several seasons. “It’s exciting,” says assistant coach Scott Layden, “because in the whole league, there are very few leaders.”

He’s also settled into a more-disciplined defensive player, while continuing to rack up steals. And the amazing part about all this is Stockton apparently just keeps getting better. After he had emerged as a senior in high school and college, his coaches were only left wondering what he would be like if they could keep him another year or two. The Jazz are finding out and liking the results.

About all that remains for Stockton is to become more accustomed to star status. “He really hates the limelight,” says his older brother Steve. “He likes the recognition, but he doesn’t like some of the stuff that goes with it.”

Yet, Stockton is a very willing speaker, making no fewer than 48 personal appearances last season. As proud as they were of his basketball achievements, Gonzaga Prep officials pointed to that statistic when they named Stockton their 1988 Alumnus of the Year.

Meanwhile, John Stockton just keeps acting like John Stockton. When he was about to enter a benefit all-star game in Portland last summer, he turned to the scorers’ table and said, “I don’t want to go in—I just want to watch this.”

Actually, plenty of people had come to the game to see Stockton play. Just don’t try telling him that.