[Jack Clary was for many years a top-flight sportswriter with the Boston Globe. He was especially known as a born storyteller, and Clary reportedly turned his gift for narrative into 67 published books before his death three years ago! The article below, from Clary’s still relatively early days in journalism, flashes all that’s to come. But the narrative oddly read a little rough, and I’ve had to fix a few things here and there to even out its wobbly presentation.

Still, it’s a Jack Clary story, and it features the Celtics’ hardnosed guard Larry Siegfried. “Siggy,” as they called him, passed away too early in 2010. His memory is starting to gather cobwebs, which is a shame. Let’s give this enigmatic Celtic his due. How ‘bout it, Jack? Clary’s story ran in the March 1970 issue of the magazine Complete Sports.]

Enigma:

- A puzzling or inexplicable occurrence or situation.

A man seeking to talk business with Larry Siegfried stopped by his table at a Baltimore motel, where he was having a postgame snack with two of his Boston Celtics teammates. The man told Siegfried of his wishes and asked if he could see him briefly after they finished eating.

“Sure, no problem,” Siegfried answered. “Why not drop up to my room in 45 minutes, and we can talk then.”

“Okay,” the man said. “That’s fine. I’ll see you then.”

“Don’t forget, 45 minutes and I’ll be there,” Siegfried reminded him.

Exactly 45 minutes later, the man walked up to Siegfried’s door and found a Do Not Disturb sign hanging on the knob.

- A saying, question, picture, etc., containing a hidden meaning; riddle.

In 1968, when they began the season, the Boston Celtics had redsigned the uniforms slightly so that there were two narrow white stripes, or green stripes on the white uniforms, running down the side of the shorts.

Larry Siegfried ran onto the court wearing an old pair of shorts, with one white stripe running down the leg. Everyone else wore the new ones.

When the Celtics opened the 1969 season, 11 players ran onto the floor wearing black, low-cut canvas sneakers, a traditional shoe worn by the Celtics. Larry Siegfried ran out wearing a pair of low-cut leather shoes of the type not worn by anyone in the league. But he did have the same style and color basketball shorts as the rest of his teammates.

- A person of puzzling or contradictory character.

Any way you cut it, that’s Larry Siegfried. He has puzzled and enraged three coaches, one general manager, two team trainers, and a couple of team physicians. He has infuriated fans in every National Basketball Association city, including his own, and has incited more than a few of his rival players to near mayhem.

His demeanor has become a subject for conversation, pro and con. Just when you are about to consign him to the lower regions of Hades, he goes out on the basketball court and makes a mockery of his critics. You get the feeling, in fact, after one of those incidents that it is you, not him, who may be wrong.

But that is Larry Siegfried’s way. He abhors convention and conventionality. He will rail upon an opponent in the fiercest possible moment, then spend most of the next afternoon visiting sick children at any number of Boston hospitals.

Billy Cunningham of the Philadelphia 76ers used to go out on the court fully expecting to engage in combat with Siegfried and often his expectations were realized. Wilt Chamberlain, rarely incited to any type of major—or minor—mayhem (thank goodness) has swatted at him like he would a pesky mosquito.

And the allusion is not lost upon Siggy either. “Those things don’t bother me,” he says. “Losing bothers me. So does winning. I like being bothered by winning, but there are a lot of things in my life that I’ll let pass by without too much of a show. I’ll be elated by winning, but I’ll not show it. I’ll be bitter about losing, and I’ll not show that either. That’s just my way.”

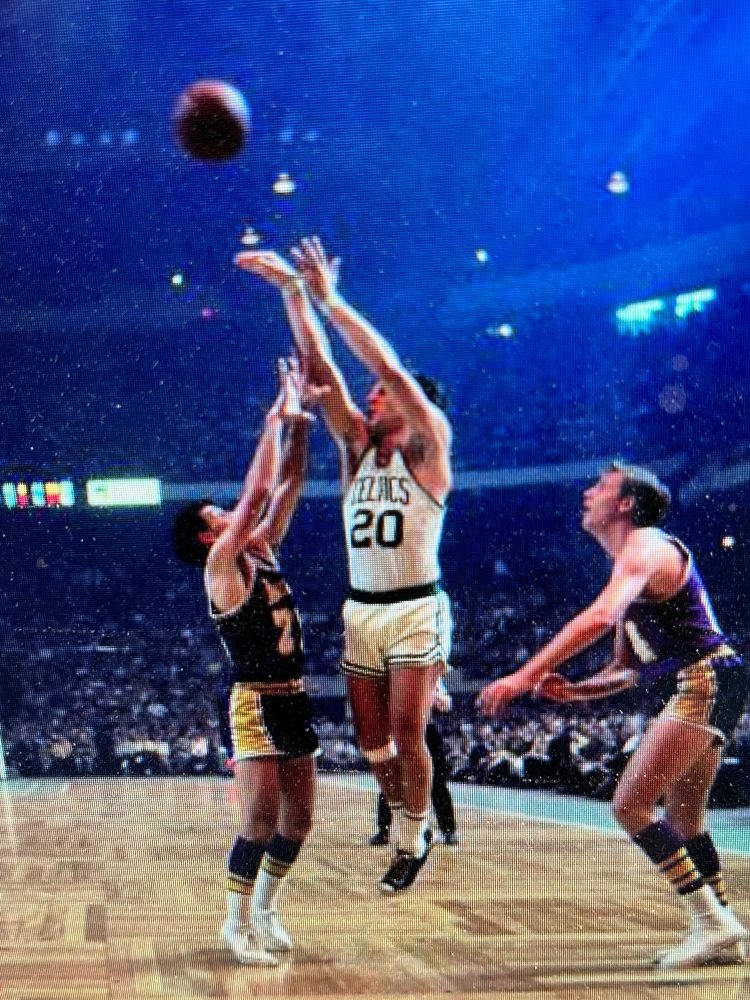

What really is Siegfried’s “way” is to keep everyone off balance. This gives great vent to his sensitivities, which are ironclad enough to withstand the tongue-lashings of Red Auerbach or Tom Heinsohn, and the cuttingly accusing looks a former Coach Bill Russell. Trainer Joe DeLauri will not cotton to Siegfried’s amazing assortment of ills. Neither will fans tone down their derisive catcalls at Boston’s number 20.

Siegfried started off his pro career being different. Captain of Ohio State’s great Big Ten champions in 1961, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Royals of the NBA and the Cleveland team in the American Basketball League (ABL). He chose Cleveland because he could not forgive the Cincinnati fans for the treatment of his Ohio State team during the NCAA finals, in which it lost to the hometown Bearcats. That action, as much as any single thing, epitomized his modus operandi: he’s not afraid to be different.

“Different? I don’t think I’m that different,” he says. “I’m my own man, if that’s what you mean. But I certainly don’t consider myself an oddball or a kook. Hell, I like the same things other people like, and I do the same things they do. But just because I may be different in the way I play on the basketball court, people think I’m strange, I guess.

“Oh, they can think what they want, because I think I really am judged by what our team has done and my part in its success.”

And its failure?

“That, too,” he nodded. “No one man can be held liable for the success or failure of a team, if it has two men or 11 men. The guys who get a lot of credit or the blame often are the ones who stand out, who do the things which are different. My style of play could be classed as different because I’m not afraid to take a chance, not afraid to go all out.

A lot of times when you take a chance, everyone sees it. If it works, fine. If it doesn’t, then they scream at you. The professional athlete must be able to take both sides.”

Not Immune to Criticism

Siegfried is not as immune to public criticism as he makes out to be. He does not like to be booed on the road. “Booing is supposed to be a sign of dislike, and I’ll admit that I want people to like me,” he says. “On the other hand, maybe you would want to consider it a sign of appreciation. When it happens away from home, then maybe you really are hurting the home team, not being a bum.”

Maybe this is really what makes Larry run: his own way of hurting the opposition. His coaches have felt that he can do a most effective job by a more consistent brand of play. This year in succeeding Russell as coach, Heinsohn decreed that Siegfried would do more shooting. Siggy is an excellent shot, and the Celtics needed someone to take up the slack of Sam Jones’ departure.

This meant Siegfried would be relieved not only of his playmaking duties to an extent, but he also would have some of the burdens lifted off his shoulders on defense. It also meant that Siegfried would have to be a thinking ballplayer, constantly on the move looking for his shot, working as an integral part of the Celtics’ offensive attack.

In the second game of the season against Baltimore, he started in the backcourt as usual. But five lackluster minutes into the game, he was on the bench. In the second quarter, Heinsohn sent him in again, this time for a minute. Heinsohn was infuriated that Siegfried wasn’t attempting to fit into his new offensive role. The coach showed it in the second half by stashing Siegfried on the sixth seat on the Celtics’ bench and leaving him there while young Don Chaney did most of the work. Siegfried’s production for the night was nothing. The team lost to the Bullets by seven points.

Heinsohn wasted no time in the next practice session to lay down the law to Siegfried, the enigma. Siegfried indeed would play the way Heinsohn wanted. He would run his tail up and down the court every minute that he was out there, and he would look for his shot.

These are things which are galling in trying to understand Siegfried. The same incidents have been repeated under Russell and Auerbach. In each instance, Siegfried was gravely warned that if he did not wish follow the gameplan, he could see employment elsewhere. To Larry, he did no wrong. In his own mind, he was only bringing trouble upon himself. Psychologists call it masochism; Siegfried has no terms or definitions for his actions.

Others, like Jerry West of the Los Angeles Lakers, do. “Siegfried can do just about everything, I guess,” West says. “He’s learned it all. But nobody could ever have taught him to go after balls the way he does. You have to have that here.”

“Here” is the heart, and West pointed to his chest to indicate just what he meant. It was the same tendency that appealed to Auerbach when he saw Siegfried as a collegian and finally when he had acquired him as a player. “A loose ball has nobody’s name on it,” Auerbach once advised Siegfried as his green light to dive, pounce, and grab.

Bears Scares

The advice is emblazoned upon his spirit. It is his personal credo as he goes sliding and crashing about basketball floors as if they were made of cushy turf instead of hardwood. He bears the scars of such antics: bloody knees, torn calves, bruised arms and shoulders. It seems from watching Siegfried that when the blood begins to flow, he carries himself a little taller, plays just that much harder.

Sounds like those are not the marks of finesse found on Chamberlain, no slouch at all-out play, or Dave Bing, Oscar Robertson, or Rick Barry. All are artists in their trade whose talent is natural and whose skills are such that they need not pounce and badger for a living.

“I don’t know any other way,” Siegfried says. “It is not an act. When I see a ball rolling free or when I think I can make an opponent lose the ball, then I go. That ball is what this game is all about. The more we have it, the better our chance to win. The less they have it, the better our chance to win.”

This is what makes him such a pest on the court. He never lets up, picking, probing, pulling . . . anything to get his opponent’s mind off his own game. “Call it a con if you want, but it’s still a form of defense,” Siegfried insists. “If he worries more about me than he does about the ball or what he’s supposed to do, then we get an edge. I make it easier on myself, too, because I take myself out of having to play the man speed-for-speed, move-for-move, shot-for-shot. He forgets about the move or he breaks the play.”

Such analysis is one of Siegfried’s basketball strong points. Russell relied upon him a great deal for masterminding on the court. Larry has good basketball sense and prepares “gameplans,” which the Russell-led Celtics used to good advantage.

It often seemed improbable that the man some people called “a flake” could be so coldly analytical and comprehending about a game in which he seemed to improvise every minute. But, then again, that is the mystery of Larry Siegfried.

“I still don’t know why people say I’m a mystery,” Larry wonders. “I know a lot of people in Boston who are a lot more mysterious than I am. Sometimes I look at them and wonder how they can get by being that way. And I guess they may look at me or you and wonder the same thing.”

You know the people who wonder about Siegfried please him inside. It is a form of attention that is one-way, not that Larry is strictly a one-way person. He knows what it is to wait, wish, and wonder if he ever would make it in the pros.

When the ABL folded, he went to the St. Louis Hawks, who obtained his draft rights from Cincinnati. He thought he was making the club until exiting the back door (it almost figures, doesn’t it?) of a team bus one day. Getting out of the front door was Coach Harry Gallatin, who yelled, “See you later, Larry. It was nice knowing you.”

That’s how Siggy found out he was cut. So, he went back to a high school teaching job in Hamilton Township in Ohio and never got closer to an NBA game than his television set each Sunday afternoon. And each Sunday, it seemed that all he ever saw was the Celtics and his old college teammate John Havlicek.

It was Havlicek who called him after the 1963 playoffs to tell him Auerbach was interested in giving him a trial. “I’m interested, but I think I belong with the Hawks,” Larry told him. “I’m supposed to report back to them.”

He did, but knowing that the Celtics would be willing to give him a trial should he be cut again. And he was.

“I saw him in college, and I liked what I saw,” Auerbach recalls. “If the Royals hadn’t drafted him, we would have. And then, all I heard from Havlicek was Siegfried, Siegfried, Siegfried. I told Larry that if he was willing to be our 12th man, we’d take him.”

That’s Larry Siegfried . . . a great bargain . . . a great enigma.