[Flipping through the stacks of old preseason basketball magazines in my West Virginia home, it’s uncanny how often an article touting an NBA coach turns out to jinx him. That’s the case with the article copied below from the magazine All-Star Sports’ 1980-81 Basketball Issue. It touts Hubie Brown and his mind-over-matter transformation of the Atlanta Hawks in the late-1970s.

When the magazine hit the newsstands in December 1980, the Hawks were off to a rocky start in Brown’s fifth season. Though many Hawks fans approved of Brown and his tough-guy persona that held players and referees accountable, many in the Hawks’ front-office had grown tired of his volatility. In January, Brown was called home in the middle of a long roadtrip for a long conversation with team president Mike Gearon. There were some unresolved issues that both parties needed to address. Among them was Brown’s presumed interest in coaching the New Jersey Nets. In an odd show of midseason magnanimity—or possibly opportunism—Gearon granted the New Jersey Nets permission to interview Brown for its head coaching vacancy. Brown didn’t get the job, reportedly in part because he refused to coach the team’s star Maurice Lucas. Brown disliked him.

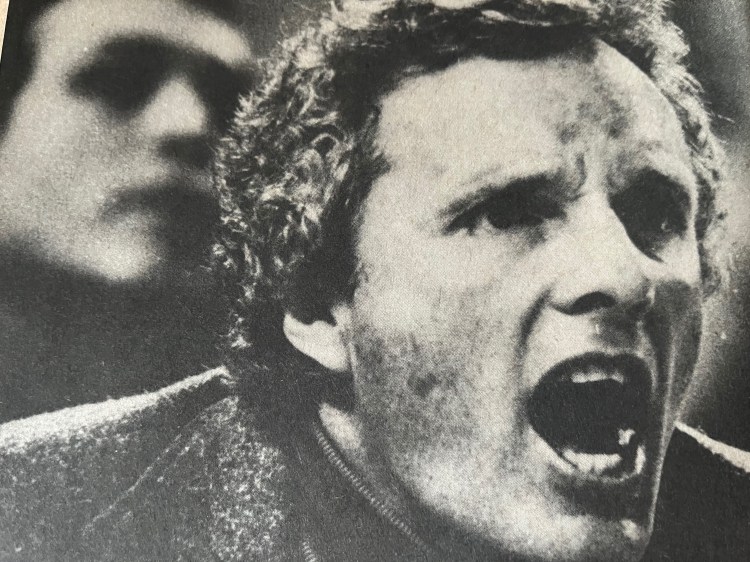

By February, Brown continued his rocky fifth season under the assumption that he’d be coaching in Atlanta for a while. His contract ran through 1984, and its remaining $690,000 was guaranteed. And so, Brown stayed true to himself. He fussed and hollered and browbeat any and all who, in his view, made mistakes that kept the Hawks from winning. But his yelling now fell on mostly desensitized ears, and the Hawks continued sinking lie a stone out of playoff contention.

By March, this disaster of a season was complete. All that remained was a final parse of the regular-season numbers: 31-51, fourth in the six-team Central Division and 29 games behind front-running Milwaukee. By April, the Hawks’ board of directors had voted unanimously to part ways with Brown and eat the remainder of his contract.

But, before all the drama and the firing to come, writer Richard Stevens took a deep dive into Brown’s rise as a hellraising, but successful, NBA coach. Today, many think of Hubie Brown as the venerable, tell-it-like-it-is color analyst on NBA broadcasts. But he was something else as a coach, too.]

****

When Hubie Brown took over as coach of the Atlanta Hawks at the start of the 1976-77 season, the franchise was one of the graveyards in the National Basketball Association. The previous year, the team had finished in last place in the Central Division with a 29–53 record, the second worst mark in the league, and had averaged only about 4,000 fans per game, including a mere 600 season ticketholders.

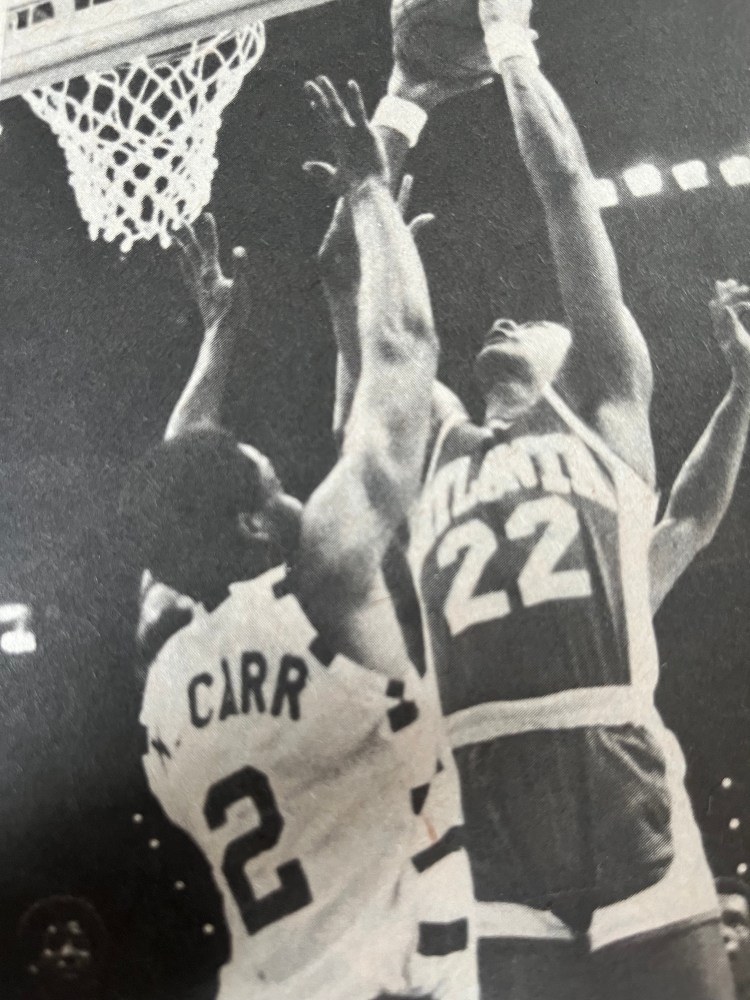

Now, thanks to the genius of the tough, no-nonsense Brown, the Hawks are alive and well. Under Brown, the team has improved dramatically each year, going from 31-51 to 41-41 to 46-36 and finally the last seasons 50-32—a record that was the best since the franchise was moved from St. Louis to Atlanta at the beginning of the 1968–69 season and earned the Hawks their first division title since the 1969-70 season. In addition, the Hawks averaged about 11,000 fans per game in the Omni, including 4,500 season ticketholders.

Despite the rapid progress under the drill-sergeant tactics of the volatile Brown, the Hawks still are an NBA novelty: a team without a millionaire. By NBA standards, they are a group of hard-working individuals with a lot less talent than most clubs, but, who—at Brown’s urging and insistence—give maximum effort and get the most out of their potential.

Brown will not have it any other way. Those who do not fit into his demanding style of coaching are dismissed, and others who understand the team concert and will work within its framework are brought in to replace them.

“I love to watch the way they scrap and play hard,” said an avid Hawks fan. “They’re not like them guys who are making one million a year. Oh, I know they’re getting big money. But Hubie Brown makes ‘em earn what they get. He chews out everybody.”

Brown tries not to show any favorites. “The individuals, players, and coaches must be subservient to team goals,” he explained. “Winners always understand that. The middle-of-the- road guys understand once you turn the corner. The losers? They never understand it.”

To prove the point about not showing favoritism, Brown’s favorite whipping boys last season were forward John Drew, the team’s leading scorer in 1979-80 and for each of the previous five years, and guard Armond Hill, the Hawks’ leading playmaker. Both Drew and Hill not only were starters, but were co-captains.

Nevertheless, in the middle of the season, the enraged Brown demoted them to the second unit for a couple of games because of “a lack of enthusiasm and intensity.” At the time, Hill and Drew, who when healthy had started every game since 1974, had started 240 consecutive games.

Later, after their reinstatement to the starting team, Drew and Hill still did not play up to Brown’s expectations, and the frank coach intentionally left them out while praising the other nine players on the team—including 11thman, rookie Sam Pellon—at a luncheon honoring the Central Division champions prior to the playoffs.

Asked why he had avoided mentioning Drew and Hill at the luncheon celebration, Brown replied, “We don’t believe in handing out accolades when guys don’t deserve it. We hope in the playoffs both will play to the potential of their athletic talent. If they do, we will be very competitive.”

The erudite Hill, a graduate of Princeton University, showed improvement during the playoffs, but Drew remained conspicuously lackadaisical until the fifth and last game against the mighty Philadelphia 76ers. But by that time, it was too late, as the Hawks were eliminated by the Eastern Conference playoff, champions.

Because of Drew’s inconsistent play, Brown kept riding him unmercifully. One of his harsher comments was: “It’s too bad we have to play four against five in the series.”

Surprisingly, Drew did not strike back verbally. Instead, he was hardly moved by Brown’s diatribe. “I really don’t pay a lot of attention,” he said. “Things like that don’t bother me. I think I am above it.”

Drew also pointed out that he had played the entire season with an injured left foot, but he emphasized that he was not using that as an excuse. During the playoffs, Drew’s play both offensively and defensively was a disappointment to Brown. Most other times, Brown had gotten on him for poor defense only.

“I’m always going to have that rap (as a poor defensive player),” Drew said. “I don’t care, because this is not my favorite phase of basketball. But I have put a lot of emphasis on defense. I’ve worked at it. I’ve worked hard.

“I don’t know what it is,” he added, “but it seems when I get beat and my man scores, some people seem to notice it more than when it happens to somebody else . . . I don’t remember anybody ever scoring 40 or 50 points on me. But I have scored 40 and 50 points against some of the best so-called defenders.”

Despite John Drew’s deficiencies on defense—as Brown sees them—the Hawks still were the best defensive team in the NBA last season, allowing an average of 101.6 points per game. That enabled them to overcome an offense that ranked only 19th in the league in both scoring (104.5 points) and shooting percentage (.464). The Hawks trap more than any team in the NBA. They press. They run. And they play all out all the time or else . . .

“We must get more shots because we shoot less than 47 percent,” said Brown. “And we must use all the incredible intangibles of basketball: turnovers, offensive rebounds, steals, blocked shots. We’ve got to convert as many fastbreaks as possible.”

Brown has figured that in order for the Hawks to win, they need 32 fastbreaks a game, and must score on at least 50 percent of them. The fiery Brown, who led the NBA in technical fouls last season with 28, emphasized that the main reason the Hawks win is that they do “the intangibles.”

“Why do I yell and scream?” he asked. “It’s to motivate them to do those things.

“Three years ago,” he continued, “I said we were going to creep, crawl, and walk. We were looking for respect, credibility and consistency. The Hawks are now consistent. We now want to be division champions every year and have our names linked in the same sentence with the Bostons, the Los Angeleses, the Philadelphias, etc. The foundation is now sound.”

And he doesn’t want it to founder again. Brown is a demanding, dictatorial leader—he even has been called a raving martinet—who is not liked by all his players. But he has gained their respect. He disdains the critics who claim he treats his players harshly.

“That doesn’t bother me,” he said. “I don’t care what other people think. At no time do we ever lose sight of the fact that we are logical, constructive, and fair. The fact that we play 10 guys equally proves that. No other team can say that.

“We give them an opportunity to display their talent. In return, they have to give us maximum concentration, intensity, and their physical talent. If they do that, they won’t hear about it. If they don’t, they have to face the consequences. They’ll be gone. It’s a simple as that. I don’t think that is any different than a major corporation or business.

“Our approach is to assume nothing and teach them everything,” added Brown. “We give them our offensive and defensive philosophy, and tell them we want it done our way. If they can’t cut it, they have to go. It’s not a slap at a player’s individual talents. He may turn out to be a star with another club. What I’m saying is that’s OK, but you have to move on. Maybe their physical talents will fit in better somewhere else.”

The players, accepting Brown as their boss in a business sense, weed out the harshness and find the underlying messages. “I was in a slump for nine or 10 games,” recalled Hill. “He attacked the point guard position before practice, after practice, and before the next game. You have to have order. He’s so organized, you can’t go up to him and say, ‘I don’t know what you wanted me to do.’”

There are times Brown admits to being too harsh on a player. When Jack Givens failed in a couple of attempts at drawing charging fouls, Brown showed his displeasure so vehemently that later he felt the need to apologize to Givens. He did it in front of the entire team. “I have to be professional enough to forget, and you (the players) must be mature enough to understand that every day is a new day,” said Brown, who is not averse to feedback on strategy from his players.

That is Brown. One minute he’s verbally assaulting a player, and the next minute he is apologetic. But he emphasizes that he doesn’t want to get too close to his players. “I tell the players, I don’t love them,” he explained. “I don’t want them to love me. Nuts to that. I don’t even believe in loyalty.”

“When we’re winning everything is great,” said forward Tom McMillen, the Rhodes Scholar. “But when we’re losing, Hubie gets tougher and tougher. He doesn’t want his players to feel comfortable losing. So he makes it so uncomfortable for you that you go all out to win just to relieve the tension.”

One player who learned quickly about Brown’s tough, structured ways was guard James McElroy, who was acquired from Detroit last season. “When I came here during the season,” said McElroy, “I realized almost right away that if I drove down the middle, I could drop a pass and know where everybody would be. If I screwed up, Hubie would let me know about it. But he’s fair. He treats everybody the same.”

At least one player—Terry Furlow—would argue that point. Furlow came to the Hawks in January 1979, and his late-season scoring helped the Hawks reach the playoffs that season. But Furlow failed to play within the team concept as demanded by Brown and was dealt to Utah last season. In the first meeting between the Jazz and the Hawks, Furlow and Brown kept exchanging unpleasantries during the course of the game.

“You weren’t fair,” Furlow shouted at Brown during one trip upcourt. “You just didn’t want to pay me what I was worth.’

“You’re an idiot,” shot back Brown. “You’ve talked your way off one team this year, and you’re working on talking your way off another.”

Another former player, Ron Lee, now with Detroit, is much kinder to his ex-coach. “I’ve never worked harder for a coach,” said Lee. “I liked him. He gets the most out of his players.”

“I don’t know if I like it (Brown’s system), but we’re better for it,” said Givens.

“One thing you can count on with a Hubie Brown-coached team,” said Boston coach Bill Fitch, “is that they will play hard every night. Unlike some teams, they won’t be down, they won’t ever let you have it (easy).”

The Hawks will play hard every game, because Brown will make them play hard; he doesn’t tolerate let downs. Brown got his toughness from his roots, and he has no empathy for the players of today.

“Those guys, they think they’ve got it tough,” he said, “but, man, I had it just as tough. No telephone, no car, I never even lived in a private house until I got married.

“My father put in 19 years in the Kearny docks n New Jersey. At the end of the war, he got laid off like everybody else. He got a job in the Singer factory for $100 a week, not bad money. But after three months, Kearny called him back and said they were reopening. He went back there, and three weeks later, they closed down for good. By now, every job in New Jersey was taken. My father lost everything. That’s loyalty. They hosed him down, but good,” Brown recalls.

Brown said that his father, Charlie Brown—“a helluva man”—then took a job as the janitor at the school that he was attending, St. Mary’s High School in Elizabeth, N.J. “He worked seven days a week for $50 a week,” said Brown. “My father taught me how to survive.”

From St. Mary’s, where he was an outstanding athlete, Brown went to Niagara University, where he played basketball under the respected Taps Gallagher, then served in the Army, where his coach was Hal Fischer, now an assistant with the New York Knicks.

After the service, he went back to Niagara for his master’s degree in teaching, and during the summers, he worked on construction gangs. “I’d be lumping for seven masons, carrying cement and cinderblocks,” said the tough, wiry Brown. “If I was slow with the cement, they’d say, ‘Hey, Jack, down the road.’ And I’d be back at Local 711 trying to get another job. That’s all we’re asking these guys (his players) to do—earn their pay.”

Brown began his coaching career in 1955 at another St. Mary’s High School in Little Falls, N.Y. He went from Little Falls to high schools in Cranford and Fair Lawn, N.J. Then, he was an assistant at William & Mary and Duke, before moving into the NBA, as an assistant under Larry Costello, his former teammate from Niagara, who then was coaching the Milwaukee Bucks.

In 1974, he got his first head coaching job since high school, when he was chosen to take over the Kentucky Colonels of the American Basketball Association. In his first season with the Colonels, the team won the ABA championship. After the next season, the league merged with the NBA, but the Colonels were not one of the four teams absorbed by the older league.

Brown, however, wasn’t out of a job very long. The downtrodden Hawks, seeking to regain respectability, hired him in 1976. They haven’t regretted it, and neither has Brown. “When the ABA folded, I was unemployed,” said Brown. “I needed a job. Then the Atlanta opportunity came along. The situation there appealed to me, because it could go only one place—up.”

And that’s exactly the direction in which Brown has taken the Hawks. And he has done it without the star system. He has done it mainly by blending a group of relatively unheralded role players and forming them into a cohesive, aggressive, confident unit.

“We’ve proved that you don’t need stars to win,” said Frank Layden, Atlanta’s former director of player personnel before leaving the Hawks last season to become the general manager of the new Utah franchise. “We can’t stand these big egos. There’s no place for them here.”

Instead, Brown gets his players to perform above their potentials. He appeals to their emotions. He rants, he, raves, he curses, but he gets results—and no one can ask for anything more. “Slowly, these guys are getting the recognition they deserve,” said Brown, after watching two of his players, Dan Roundfield and Eddie Johnson, get named to the Eastern Conference All-Star team last season.

Brown also is getting the recognition he deserves—as one of the outstanding coaches in the NBA. “It’s all I ever wanted to do,” said Brown. “Any level, any place, I just wanted to coach.”