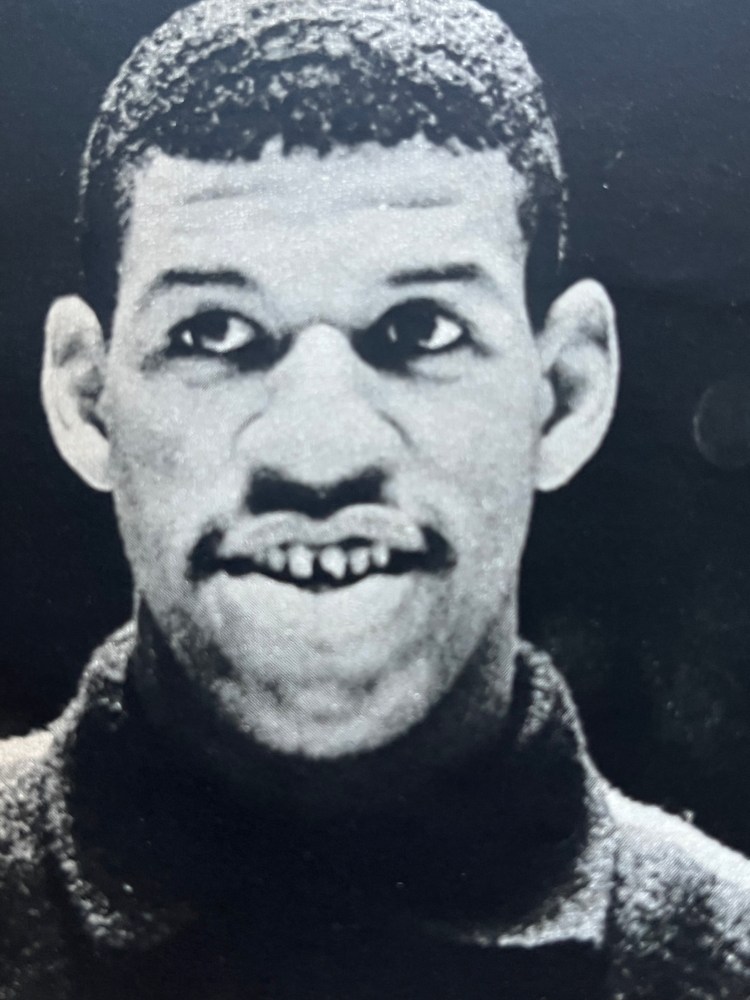

[In the run up to the 1967 NBA draft, Detroit and Baltimore flipped for the consensus top pick, Providence guard Jimmy Walker. Detroit won the coin toss and took the 6-feet-3 Walker, widely regarded as the “next Oscar Robertson” and the league’s next great point guard. There was just one huge problem. The Pistons already had a great young point guard in Dave Bing, the reigning NBA Rookie of the Year. In those days, most coaches were wary of pairing two point-guards in the backcourt. In theory, point guards couldn’t gel. Both needed the ball to excel. They’d get in each other’s way.

And so, Walker spent much of his rookie season planted on the bench watching Bing battle with the real Oscar Robertson for the NBA scoring and assist titles. “BINGO,” the public address announcer would chatter whenever Bing scored. Typical of Walker’s if-only pro career, had Baltimore won the coin flip, the Bullets’ guard-friendly coach Gene Shue probably would have handed him the ball and said, “Go,” just like he did with Earl Monroe, the player selected after Walker.

This brief article, from the March 29, 1968 issue of the Christian Science Monitor, checks in with the rookie Walker and tells the story of rise from the hardscrabble streets of Roxbury, Mass. At the keyboard is the veteran NBA scribe, Phil Elderkin, also known for his column in The Sporting News.]

A lot of kids who grew up in the Roxbury section of Boston with rookie Jimmy Walker of the Detroit Pistons are in jail now or worse, products of their environment. Walker made it out of Roxbury mostly because of Sam Jones of the Boston Celtics.

The first time Jones saw Jimmy, the boy was 16 playing Settlement House basketball and drifting along in a Boston trade school. College, if it ever entered his mind, seldom remained very long. You don’t do things in this world without money, and Walker’s mother worked in a laundry.

Jimmy didn’t have the marks either. He had once been told by a teacher that if he had any ideas about continuing his education, he had to scrap them and learn a trade. Sam Jones never bought the suggestion. He saw the whole Jimmy Walker, not just some marks which appeared on a report card. After talking with Jimmy and scrimmaging against him, he was sure he had a prize.

So, by paying his tuition for two years, Jones set it up that Walker could go to Laurinburg Academy. This is the Black prep school near Fayetteville, N.C., which Sam Jones also attended. It was a 22-hour bus ride from Boston, and Walker’s stay there cost Jones $1,200 [today, about $12,000].

Jimmy was at Laurinburg for two years before Providence College offered him a scholarship. By the time Walker was out of his freshman year at Providence, he had led his prep school and college teams to 65 straight wins.

In the summers, Jones and Satch Sanders, one of Sam’s Celtic teammates, would play Walker and any other Settlement House player who happened to be around, two-on-two on one of Roxbury’s macadam courts.

“Sanders used to try to get me to let the kids win once in a while,” Jones said. “But I told Satch it’s not a good idea to let anyone beat you. ‘If Walker is going to take me on the court,’ I told Sanders, ‘he’s going to have to earn it.’

“All it really showed is that I think like a pro,” Jones continued. “I couldn’t stand losing to a couple of kids, no matter how good they were.”

But when the time finally came when Walker was in a position to pay money back to Sam, Jones wouldn’t take it. “I wouldn’t take it because it wasn’t a loan,” Sam explained. “It was a gift. The mere fact that Jimmy chose my number [24] to wear on his uniform was good enough for me. But I did tell him once that if he ever found a boy playing basketball with the potential of Jimmy Walker and the kid didn’t have any money, I hoped he’d help him.”

Walker, with a 30.4 scoring average his senior year at Providence, was the first player picked in last year’s NBA college draft. He signed a four-year contract with the Detroit Pistons for a reported $250,00.

Although Jimmy still ranks high among today’s rich blend of young basketball hopefuls, he has not achieved the instant success with Detroit which was predicted for him. Specifically, he has not scored big in the pros, the way he did in college, although he has an arsenal of shots.

“Look, I wouldn’t blame Jimmy too much for what’s happened,” said Pistons coach Donnie Butcher. “Walker was the take-charge guy in college. He controlled the ball most of the time. Providence would clear out one whole side of the court and let him go one-on-one. He got playing time and the exposure he needed to make All-America.

“But it’s a little different situation in Detroit,” Butcher continued. “We already had a leader in Dave Bing when Jimmy got here. Bing, in addition to passing well, led the league in scoring this year. Basically, Walker is the same kind of player, only you can’t have two of them on the floor at the same time. Their styles conflict.

“So, Jimmy has had to change his game. He’s had to play more defense. He’s had to learn to go without the ball. He isn’t scoring big [12 points per game]. But he’s making the contribution by doing other things—things which don’t always show in the box score.”

Walker, powerfully built and standing 6-feet-3, is not too unlike the man who discovered him. Sam Jones. Both are explosive scorers in close. Both have the ability to shift gears while running. And both can hang in the air for what seems like seconds before deciding whether to shoot or pass off.

Jimmy didn’t exactly grow up wanting to play for Boston. That didn’t become an overpowering emotion until after he met Jones. But all the ingredients are there for a Celtics-Pistons trade after this season. Providing Boston is willing to deliver a frontline player in return for Walker.

Right now, with Boston and Detroit engaged in a best-of-seven playoff series, Jones and Walker are seeing a lot of each other on-court. “Sure, I guard Jimmy sometimes when he has the ball, and sometimes he guards me,” Jones said. “But we never talk to each other on the floor.

“We might get together after a game, or Walker might even come out to the house for dinner,” Sam continued. “But Jimmy is just another enemy body what he’s wearing a Detroit uniform.”

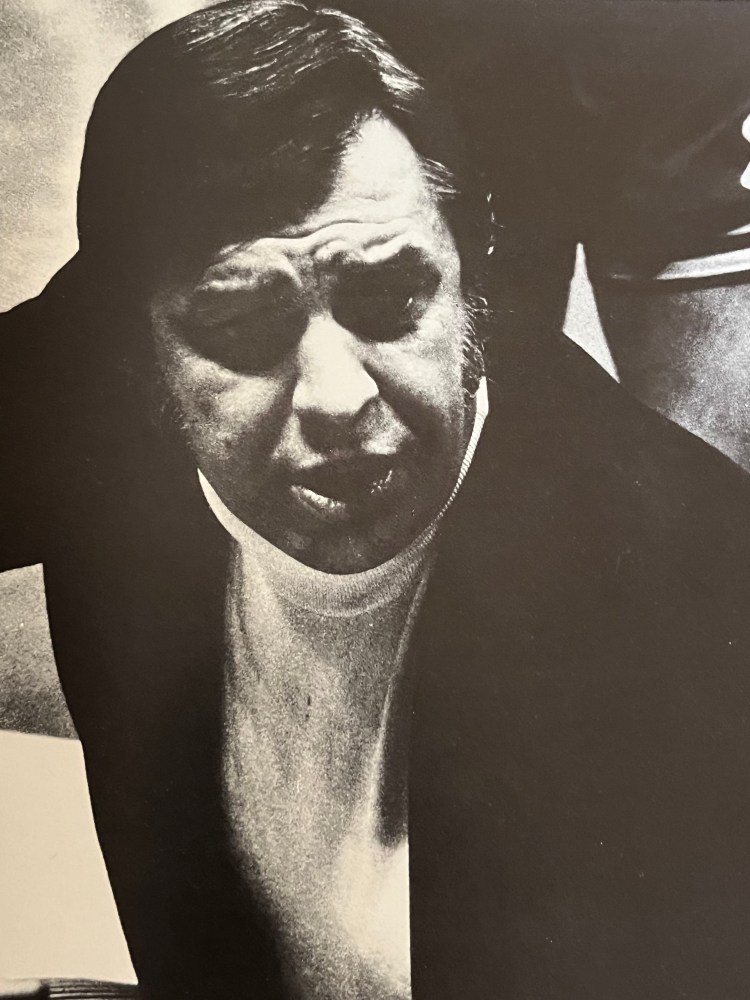

[Walker arrived for his sophomore season with a tire around his waist. With Detroit’s backcourt well stocked for the season, Walker had to work his way back into shape, back into the good graces of the 30-year-old Coach Butcher, and back into the rotation. With his slow start to the season, the whispers started: Walker was no Oscar Robertson. He was a colossal bust!

But so were the Pistons to start the 1968-69 season, lacking a viable center to police the paint. Coach Butcher, trying to save his job, agreed to trade Walker to New York for veteran center Walt Bellamy, the answer to his prayers. But before the trade was finalized, Butcher was abruptly fired. Or, as they called it in Detroit, “got the ziggy.” His replacement, the motor-mouthed Paul Seymour, nixed the trade. Seymour insisted, though out of no love for the youngster Walker, that New York had to take Detroit’s Dave DeBusschere. Why? DeBusschere was tight with the team owner Fred Zollner, who was famously prone to the ziggy. Seymour worried that all DeBusschere had to do was snap his fingers, and Zollner would can him. The rest, of course, is NBA history. DeBusschere became “the glue guy” and the catalyst for those great early-1970s Knicks teams.

Seymour may have kept Walker, but he didn’t want to play him. Or improve their strained communication. “Why should I have to wet nurse a guy who’s signed a contract for a quarter of a million dollars,” he snapped. This Q & A with Walker pretty much tells the story of this strained communication, another tale of a difficult coach stymieing a talented player’s career. As Walker claimed, he wasn’t a bust. He couldn’t impress sitting on the bench. The Q & A comes from the March 23, 1969 issue of the Detroit Free Press. Asking the questions is the veteran Jack Saylor.]

Q—You were a great college player and showed a lot of promise as a rookie, but nearly everyone seems to think you weren’t the same player this season. First of all, do you agree with that?

A—No, I don’t—not at all.

Q—Then what is your evaluation of this season—what has been the problem?

A—I wasn’t used to sitting on the bench. I was a substitute, but toward the end of last year, I thought I came into my own. I played behind Dave Bing, Eddie Miles, and Tom Van Arsdale for quite a while. It was told to me that it was because they were veterans, and I understood this. But this year, I think it was a different story.

Q—How about this year?

A—All I saw or heard was how inconsistent I was playing. But the only way I can play consistently is to have consistent time, and for the last two years, it hasn’t been. I’ve played what I thought were very good games—games we have won. I scored a lot of points, passed well, and done everything well. And we have won the ballgame. Then, in the following game, I haven’t played at all—and they talk about inconsistency. Then I hear that my attitude is bad.

Q—What about your attitude?

A—I’m a ballplayer with a lot of pride. I know what I can do, and I don’t think I’m the only one who knows what I can do or can’t do. Then they say, “We know what you can do, but you haven’t been doing it.” Well, I don’t think I can do it from a sitting position.

Q—How did all the changes on the team affect you?

A—We went through a great number of changes in coaches and players, and I thought it was all going to be for the better. But I think it turned out to be worse. With the attitudes, it just seemed like the majority of the season we were playing against each other. I’m not going to say exactly just what I think it is. I don’t think it would be beneficial to me. But the fact is when the new ballplayers came in—and even the old players—they would be in the game and make a few mistakes, you knew you were coming out . . . there was tension. Anybody could see it. It wasn’t something that was hidden. There was tension. It was nothing racial—that was 99 percent overplayed. We got along very well together. We still do, but I don’t think the guys really enjoyed the season—and I don’t mean just the losses.

Q—Did you personally have the feeling that if you made a mistake or two, you would be pulled right out of the game?

A—Definitely—not that I just had that feeling. I KNEW it would happen. It happened last year, and it happened this year. It’s a heckuva thing with a ballplayer like myself, with as much pride as I have. Maybe I haven’t been in the league seven, eight, nine years, but I’ve probably got just as much pride as a guy that’s been in the league that long.

Q—Does it shake your confidence?

A—No, nothing shakes my confidence. But at the same time that you’re playing, it affects you.

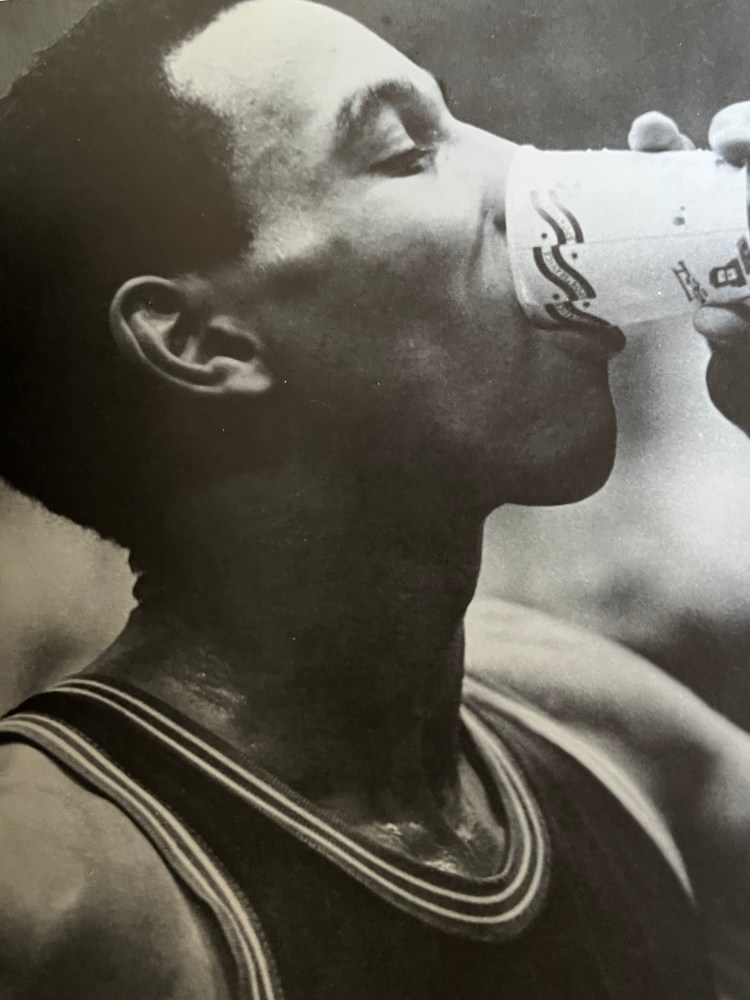

Q—Both coachers this year were upset about your weight—are you inclined to have a weight problem if you don’t watch it?

A—My weight fluctuates. My body retains a lot of liquids. Now at one time, it was my fault—I admit this. But at a time when my weight did decline, my scoring went up, we were playing well, and winning a few games. But then I sat down.

Q—And you have no explanation for this?

A—No one ever gave me an explanation. The only thing I know is what I see in the paper the next day or hear on the radio. That I’m gonna be traded for such-and-such . . . and it’s a heckuva thing for a ballplayer to go from day-to-day hearing that he’s gonna be traded and then have someone tell me that my attitude is bad when I know this is impossible. That’s the last thing that’s going to go with me as far as basketball is concerned because it’s my profession.

Q—Did anybody ever sit down with you and talk things over?

A—No, no one asked me how I felt. We never had a heart-to-heart talk. When Paul Seymour first came to the team, the only thing I heard was what I read in the paper—he thought I was a “nice kid.” I don’t know what that meant. Okay, if he thinks I’m a “nice kid,” I think he’s a “nice kid,” too. I realize he came into the league in a difficult position because we were losing, and the schedule was at its worst. But when the schedule got to be a little bit better, I don’t think things improved. I’m not going to say whether it was his fault or not.

Q—How do you feel you got along with the coaches—Donnis Butch and Seymour?

A—I thought I got along better with Butcher than I did with Paul. Butch was the hard-nosed type . . . Paul probably is too. It seems like both are from the old school. Maybe Paul thought he understood me and the rest of the ballplayers, but I KNOW he doesn’t understand me. How can a person understand you just by seeing you play? He’s never talked to me—he doesn’t know what I feel. If I sit down for 15 games in a row, he doesn’t know how I feel.

Q—Then you think it’s a problem in communication?

A—I know that’s what it is.

Q—Did the situation deteriorate after you were fined a couple of times?

A—Take for instance when I missed the plane. We had a discussion even before this happened about what might happen, what’s going to be kept between the team. I missed the plane—this again was my fault. I admit that, okay? I got another flight and made the game. When we got back to Detroit, it’s [the missed flight] in print THAT BIG. We were losing, so we have to blame something on somebody. It seems to me that things are always being pointed in my direction because so much was supposed to be expected of me, probably because my salary and so forth.

Q—Did the constant trade talk upset you?

A—Trades are a part of the league—and the DeBusschere trade lets you know anybody can be traded. I know I could be traded, too, but I heard it constantly. I kept hearing it from everybody but the coach. All I heard about was my bad attitude. I think to myself that I’m too good to sit on anybody’s bench. I really can’t respect the man for the things that he said and reacted toward me. I can’t respect him as a man because all he thinks of me as a kid coming out of college with a big contract.

Q—Does that mean you don’t think you could play for him if he’s still the coach next year?

A—I think I can play with anybody. The fact of me not playing for him would depend on whether he played me personality-wise. Or that he was playing me because I had the ability.

Q—What’s your reaction to the feeling some hold that you and Dave Bing can’t operate well together in the backcourt because your styles are too similar?

A—I think that’s wrong. If two ballplayers are aiming for the same thing, if both players want to win the game, then unselfishness comes in. It’s when unselfishness goes out the window that you lose. Dave and I have played games together—I mean 36 or 40 minutes—and we’ve won. Then, all of a sudden, we’d be separated.

Q—Have you ever had any regrets about picking the NBA?

A—To me, the league is beautiful. I love the league. I have no regrets being in the NBA compared to the ABA. The NBA was explained to me before I got here by Bill Russell and Sam Jones. They told me a lot of things probably would happen. But nothing like this, like what has happened to me personally.

Q—Can having four “first-string” guards be a healthy situation? Or, do you think it’s working the other way instead?

A—I don’t think there’s any team in the league that has better guards than we have. I don’t think there’s any situation we couldn’t handle as far as our four guards are concerned. But as far as the way we are handled, that’s not up to me. It’s a drawback in a way, because somebody’s got to get less playing time.

Q—You mentioned your big contract. Do you think it made you less “hungry” as a player than you might have been otherwise?

A—No, I don’t—and I’ll tell you why. My playing time, just like my weight, fluctuates. I never know how much I’ll play. On the day of the game, I might go over to the Fisher YMCA for 90 minutes, maybe two hours, and work out hard . . . running, wind sprints, and so forth, just because I don’t know how much playing time I’ll get that night. The way it’s been, there’s no way I could play a good game if I hadn’t been working out a lot.

Q—Do you think you’ve improved at all from your rookie year?

A—No, not at all. In fact, I’m about the same now as when I left college, maybe even a little worse because of the playing time. I can’t just play three minutes here or three minutes there. My game is an all-around game. I can’t come in and just pass or just shoot. I just react to whatever the situation is.

Q—You’ll be 25 in a couple of weeks and should have a great career ahead. What about your future with the Pistons? Do you want to be traded?

A—I would like to play here. I’ve met some beautiful people since I’ve been in Detroit, and Detroit is a nice place to play. But I don’t think I would like to play anyplace if I had to sit on the bench and watch. If you want to talk about past experience, then, no, I wouldn’t like to play here. I don’t think I’ve really had a chance to play like I think I can play.

[In his third season, 1969-70, Walker got lucky. Paul Seymour got the ziggy, and the Pistons hired Butch van Breda Kolff. VBK, known for running an open, freelance offense, saw no reason why Walker and Bing couldn’t coexist—and thrive—in the same backcourt. He was right. Walker’s minutes jumped to 35 per game , and his scoring average nearly doubled to 20.8 per outing. In January 1970, Walker even appeared in his first NBA All-Star Game.

Up next is a brief, condensed Q & A that catches Walker during the next season, 1970-71. Gone are the whispers that Walker was a bust; back are the popular buzz over his nifty ballhandling and uncanny scoring ability. The Q & A ran in the December 13, 1970 issue of the Detroit Free Press. Walker’s inquisitor is Curt Sylvester, who covered the Pistons in the 1970s]

Q—Your scoring average is lower than last year. In spite of that, are you satisfied with your own game.

A—So far, I’m disappointed in a way, because I don’t think I’m really asserting myself at times when I should. I’m slowly coming out of it now. In the past, I think I was a little too casual about my game. My team game is coming along better than it was. As far as that’s concerned, I’m satisfied. But there are a lot of things . . . it’s early in the season, and I hope these things will be ironed out soon. I just don’t want to take too long.

Q—The Pistons are unusual in having two high-scoring guards in Dave Bing and yourself. Is it difficult to work with another high-scoring guard?

A—No, I don’t think so. When we got here, this was a myth that was created—Dave and I couldn’t play together. This was created only because no one had ever tried it. People tend to forget when you have two guards capable of scoring, and if one of them or both of them want to win, naturally they’re going to pass the basketball. They have to. I couldn’t consistently come down and keep the basketball from Dave and say to somebody else that I want to win. It has to be a team. I know when Dave wants the ball, and he knows when I want the ball. I believe we work well together.

Q—What happens when you’re both having a good night?

A—Then each of us has to give himself up for the other. It just depends on who happens to have the ball at a particular moment, whatever the situation or the game brings about.

Q—In your first year in Detroit, you got a reputation of being a hard player to handle. Did you change or was that a bad rap?

A—No, I didn’t change. When I got here, it wasn’t that I was tough to handle. I don’t know why anyone wanted to “handle” me. You handle packages and things like that. It was no problem at all. But I think I resented the fact of not playing, because I have been playing all my life. I was sitting down, and when you feel you have a contribution to make, that really takes something out of you . . . to sit there constantly and know you have nothing to offer. Or, this is what people think—that you have nothing to offer—and you’re not given a chance to offer anything.

Q—Your average jumped about 10 points, and you seemed to find yourself when Bill van Breda Kolff came along. Why?

A—Although I scored last year, I wasn’t satisfied because we still lost. But I scored last year . . . I played much more last year. I have to say he had a lot to do with it, because he was the first one that played Dave Bing and me together. After a while, I saw it was a good thing because Dave was scoring and I was scoring. So, someone must have been wrong in the past. Dave was getting his points, and I was getting my points.

[Walker got his points with the Pistons through the 1971-72 season. But with van Breda Kolff now gone, the Pistons kept trying to unload Walker. It was the same old story. New Pistons coach Earl Lloyd considered Walker a poor fit in the backcourt with Bing. In fact, when Walker appeared in the 1972 NBA All-Star Game, Detroit GM Ed Coil made the rounds soliciting trade offers and tried hard to push Walker on Baltimore for Phil Chenier. No dice. In August 1972, Coil finally rolled snake eyes. He traded Walker to Houston straight up for veteran guard Stu Lantz. When asked about the trade, Walker replied, “I’m not surprised at the trade. It’s only disappointing to me in one respect . . . it seems as though I’m being traded as a scapegoat, a troublemaker. I don’t like that title. It developed back three or four coaches back . . . when I missed a plane or something. These opinions have been passed on me, purely from what people hear.”]