[Happy almost New Year. This will be the 104th article published on this blog in 2023 and likely the final post of the year. This last one, written by the entertaining Bob Rubin, is pulled from the magazine Argosy’s Pro Basketball Yearbook, 1975-76. Rick Barry on the cover. The article’s headline speaks for itself, and Rubin does the rest. Until 2024, a warm season’s greeting From Way Downtown.]

****

Ludicrous as it may sound to normal-sized people, 6-feet-9, 225-pound Cleveland Cavaliers’ center Steve Patterson is small for an NBA pivotman. So, when he plays against one of the league’s real whoppers, Patterson must do something to make up for his size disadvantage. What he does is hold. And push. And hit. And scratch. And elbow. And knee. And . . . you get the idea.

One night in Detroit, he was matched (or, more accurately, mismatched) against the Pistons’ massive 6-feeet-11, 260-pound Bob Lanier, whose great bulk and delicate, shooting touch forced Patterson to use every weapon in his defensive arsenal.

Thud. The sound that was heard was Steve Patterson hitting the deck.

“Suddenly, I don’t know how he did it . . . I was leaning on him, hammering him, practically hanging on him, and he just wrapped his arms around me and threw me to the ground like I was a rag doll,” Patterson said. “It was like I wasn’t even there. I did a complete four-point landing, landed on both elbows, bruised them both, and they really swelled up.

“Bob didn’t even appear to be angry, because as soon as he did it, he looked at me, offered his hand, and helped me up. But he gave me a graphic illustration that, all right, you can play rough and you can play strong, but there is a line past which you cannot go.”

If there is such a line, it’s drawn just this side of the hospital emergency room. Pro basketball long ago dropped the pretense of being a non-contact sport, and with the players getting bigger, stronger, and faster every year, the contact rose correspondingly more violent—and destructive. A look at last season’s casualty list offers dramatic proof of the game’s hazards. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Dave Cowens, Ernie DiGregorio, Jim McMillian, Gar Heard, Lou Hudson, Cazzie Russell, Austin Carr, Jim Chones, Bob Love, Norm Van Lier, Bill Bradley, and Bill Walton were among the big names in the NBA who missed a substantial portion of their team’s games in the first half of the year.

These were similar to the carnage in the ABA, where commissioner Tedd Munchak fired off a memo to all teams warning that unnecessary roughness would be punishable “by fine, suspension, or both to the limits, at my discretion, not to exceed $250,000.”

Whole teams are often decimated in the backboard jungle. Last February, the Buffalo Braves were reduced to three healthy guards, because DiGregorio was slow in recovering from surgery on his right knee and Lee Winfield was out with multiple ligament strains of his left ankle. “Even if they let both teams play rough, it doesn’t do us any good because we can’t outmuscled anybody,” claimed Braves’ coach Jack Ramsay, whose team depends on speed more than intimidation.

The following month, the Atlanta Hawks found themselves down to a bare minimum when Lou Hudson, Tom Henderson, John Wetzel, John Drew, and John Brown were all nursing injuries at the same time. “We played an overtime game in Cleveland with just six guys,” moaned Hawks’ coach Cotton Fitzsimmons. “There’s no way we can practice. All we do on an off-day is whirlpool.”

For Henderson, the Hawks’ outstanding rookie guard from Hawaii, the contrast between the amount of contact allowed in pro ball and college is simply astounding. “In college, a defender can’t tough his man,” Henderson said. “But in the pros, he can damn-near beat him to death.”

Why has mayhem become such an integral part of a game that’s appeal has traditionally been its grace and speed? Ironically, to a considerable degree, it’s because the pros are such outstanding offensive threats that they would simply be unstoppable if the defender wasn’t allowed liberal use of his hands, elbows, knees, and whatever other part of the body he can employ without the refs seeing it.

Then there is the sheer size of the players. The nature of the game dictates that most of the action takes place in a relatively confined area under the baskets. But 10 huge, muscular men in that little patch of real estate, let them run, jump, and throw their bodies around, and you are bound to have lots of memorable collisions. And these giants wear no padding like their football brethren. The contact is bone to bone. Ouch!

The players and coaches complain about the officials, claiming they allow too much rough stuff or that they are inconsistent in how much they allow. No one would argue that the level of officiating in pro basketball could and should be upgraded, and the NBA has taken a step in that direction by assigning a third official to all exhibition games this year. He worked along the sideline adjacent to the scorer’s table from one free throw line to the other and has limited responsibilities—the 24-second clock, halfcourt violation calls, for example. That freed the other two refs to pay more attention to such things as elbows, knees, hips, etc.

But no officiating changes are going to eliminate rough play from professional basketball. It has become part of the game, every aspect of it.

Like driving to the basket. “Every time I start my move toward the basket to attempt to score a field goal for the Phoenix Suns, a scene flashes into my memory from the Saturday afternoons my twin brother Tom and I used to spend in our neighborhood movie house,” said Dick Van Arsdale, whose hell-for-leather forays toward the hoop are a key to his game.

“We loved Westerns when we were kids, and one of our all-time favorite flicks had a scene in it where the hero had to prove his bravery to a tribe of hostile Indians, so they’d spare a little group of settlers down in the valley. They offered to let him run the gauntlet, and they would spare the folks if the cowboys survived. They made him sprint down the lane between two lines of their meanest, toughest braves while they swung at him with their war clubs, knives, lances, fists—you name it. The hero made it, I remember, but boy was he a bloody mess!

“Trying to make a layup in the closing moment of an NBA game can be as dangerous and painful as trying to run an Indian gauntlet. But a player doesn’t dare flinch or cringe or fear to make an attempt—unless he’s ready to look for another line of work. Making layups, no matter how tight the opening, it’s just something every pro must do. Defensive players whack at you and the ball as you move past them, and often, if you get past the first line of defense, there will be a giant like Bob McAdoo or Nate Thurmond under the basket sort of grinning at you and ready to swat you down like a pesky mosquito.”

Suppose Van Arsdale misses the layup at the end of his drive. That’s when the real fun begins. “Next time a pro basketball player makes a remark about ‘the butcher shop,’ don’t look for a bargain sale on pot roast,” said Washington Bullets’ star center-forward Elvin Hayes. “That’s the nickname we have for the area under the baskets, where the rebounding action takes place. The name is a good one, because every time a shot is taken, there are going to be hips and elbows and chests and heads flying around, slamming and bumping.

“During wartime, they say you can’t find any atheists in foxholes. You don’t find many trying for rebounds, either. It’s a rough proposition, one of the roughest you’ll find anywhere in sports, considering how big and strong guys are in the NBA. Rebounding happens to be one of the ways I make my living, so it’s just something I force myself to tolerate, no matter how many bruises I wind up with.”

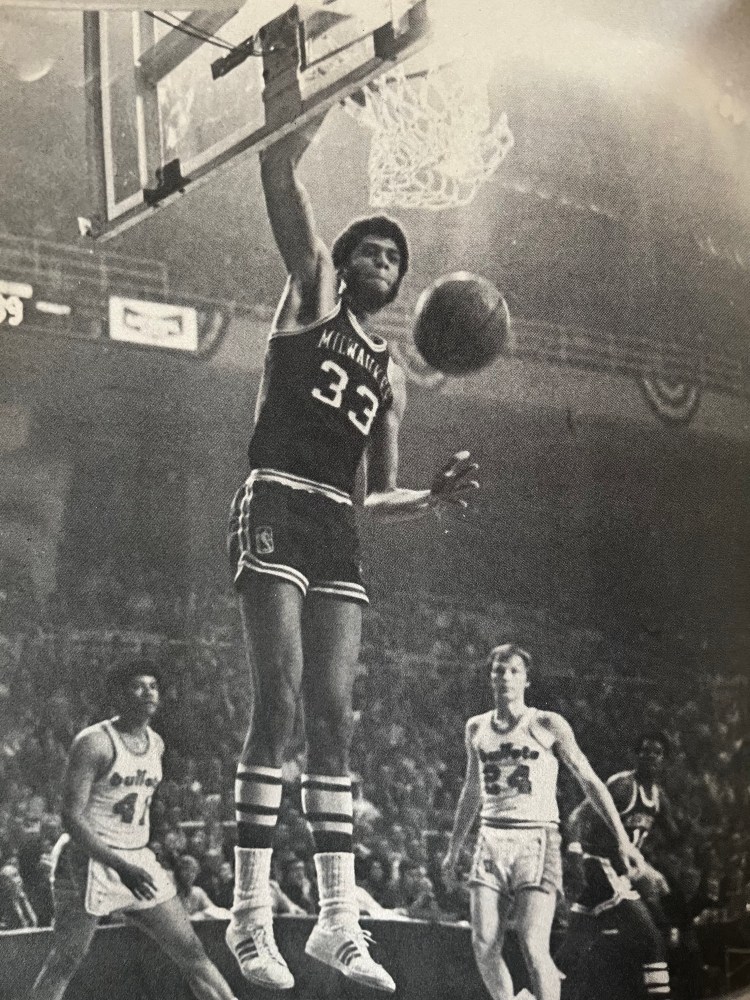

Along with most other categories, Abdul-Jabbar probably leads the league in bruises. It’s a tribute to how difficult he is to defend. When Special K gets the ball, he looks unstoppable. He makes scoring appear easy. It isn’t. Nothing comes easy in that no-man’s land under the basket.

“Believe me, there’s nothing easy about hitting a shot when a big 260-pounder like Bob Lanier is pushing against you,” said the big, bad Buck turned Laker. “When you bump into a man like Bob or Nate Thurmond in a scramble after a rebound or when you’re trying to shoot, neither of you wearing pads, you feel it. You keep feeling it for a couple of days afterward, too.

“Other teams know I’m pretty hard to keep from scoring once I start my shot. It stands to reason they would try to keep my point totals down by forcing me—in very physical ways—away from where I want to be on the court. The tug-of-war situation that takes place between centers—the defender with his forearm and elbow, and sometimes even his shoulder in the offensive center’s back, both of them pushing as hard as they can—are wars for position.”

As in any war, there are casualties. Ask Steve Patterson.

Most guards are smart enough to stay out of elephant country, but that doesn’t mean they don’t also take a beating. “Close guarding is something any shooter learns to expect,” said former Laker star Jerry West. “You don’t mind it unless the referees let things get out of hand. I’ve had men grab my hips so hard and try to keep me from going where I want to that afterward you can almost see their fingerprints on my skin.

“Other guys wait until you’re up in the air and vulnerable, then poke you or knock you off balance. It’s very frustrating when this happens, it’s one reason I was personally so grateful that the Lakers emphasized the fastbreak the last couple seasons of my career. I was called ‘Mr. Clutch,’ you might say, but more often I felt like ‘Mr. Clutched!’”

The pros accept rough play is part of the game. It’s when an opponent steps over that often hard-to-define line into “dirty” play that tempers flare and fists fly.

The Chicago Bulls, and in particular the fiery guard Jerry Sloan, have often been charged with dirty play. In one rough home game in April 1974 against their arch-rivals, the Milwaukee Bucks, the crowd and a national TV audience must have thought they tuned in one of those fight cards instead of a pro basketball game.

First Sloan and Oscar Robertson squared off, and in the ensuing fracas, Sloan delivered a kick to Ron Williams’ kisser that would’ve done Bruce Lee proud. So much for the preliminaries. The heavyweights were ready to swing into action. Later in the game, incensed by Abdul-Jabbar’s liberal use of his elbows, Bulls’ center Dennis Awtrey chased his lanky opponent down the court, grabbing his jersey with his left hand, spun him around and delivered a stunning Ali-like right to the face that left Abdul-Jabbar in a daze. It was a rare turnabout for Abdul-Jabbar, who has taken swings at overzealous defenders several times in the past.

Awtrey got the hero treatment from the crowd as he jogged to the dressing room after being kicked out of the game. “It’s one of those things you decide to do on the spur of the moment,” he said, “and probably if I had stopped and thought about it, I wouldn’t have done it. But I’ll tell you this much. He hasn’t elbowed me since then.”

As for Sloan, he is the personification of wounded innocence when his basketball ethics are questioned. The same goes for Bulls’ coach Dick Motta when it’s suggested that he teaches karate instead of basketball.

“Sure, we scramble,” said Sloan. “Sure, we jump up for loose balls. But if other teams wanted to hustle, they could do that, too. There’s no law that says we are the only team that can do it. It’s not bush basketball. Hell, if I run my tail off, that doesn’t make me a crazy man. I know I shouldn’t get so upset. But I’m just tired of people calling us bush, or dirty players.”

Said Motta: “I’ll never know why a guy like Sloan, who gives so much to the game, is ridiculed by his peers. It’s a problem for him and for all of us. They call him a dirty player, and he’s not a dirty player. He’s a defensive genius and the most unselfish player in the league.

“I’ve been watching him for six years, and I’ve never seen him punch an opponent the way they punch him. I’ve never seen him undercut or try to hurt anybody. Sure, he’ll grab and hold and use tricks. Everybody in the league tries to get away with things if they think the officials aren’t watching. That doesn’t justify the ‘Put on the Boxing Gloves, Here Come the Bulls’ headlines we read all over the country.”

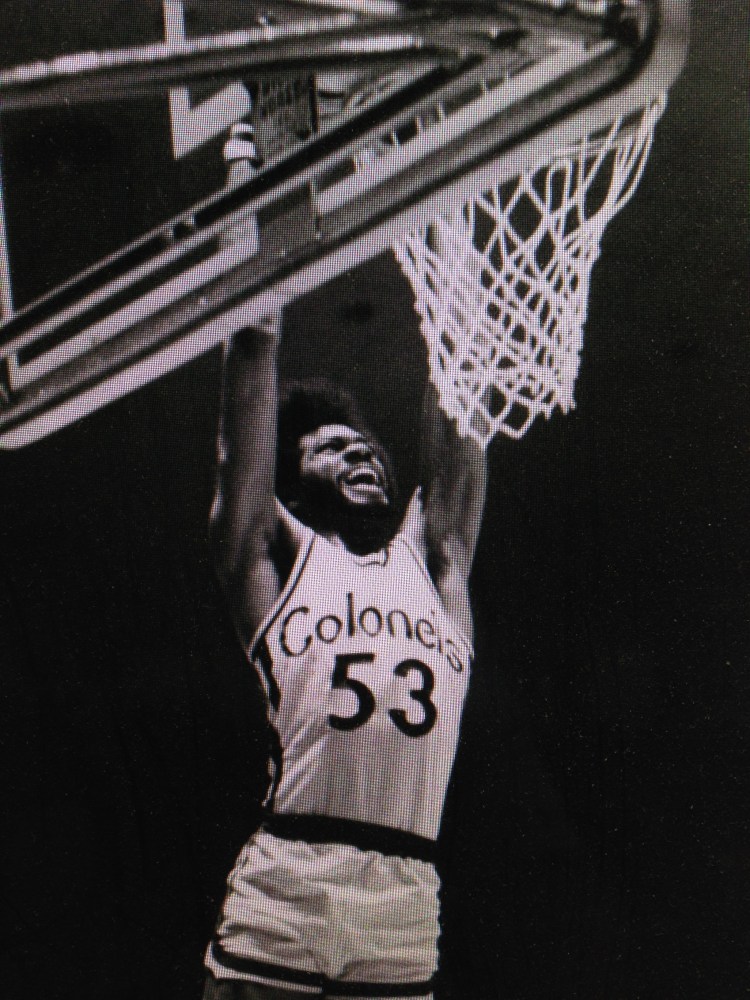

The ABA takes no backseat to its old arrival when it comes to contact—legitimate as well as the kind that produces swingouts. Because they are so hard to defend against, the game’s giants are prime targets for rough stuff. As we’ve seen, Abdul-Jabbar gets more than his share, and so does the ABA version of Abdul-Jabbar, Kentucky’s Artis Gilmore. Like Abdul-Jabbar, Gilmore has had to draw a line beyond which an opponent treads at his own peril.

Gilmore flattened Virginia Squires’ rookie William Franklin in a fight after Franklin jumped on him in a game near the end of the 1972-73 season. Midway through that season, Awesome Artis threw Denver’s Byron Beck to the floor, climbed on top of him, raised a ham-sized fist . . . and reconsidered. Three weeks later, the late Wendell Ladner of the Nets provoked Gilmore into another scrap. “We used to call him a teddy bear,” said Indiana strongman George McGinnis, a Philadelphia 76er this season, “but not anymore. He’s starting to get mean. You’ve got to watch out for him.”

“I’m not a fighter,” said the normally docile Gilmore. “I don’t really like to fight. But I don’t like to get pushed and shoved.

“You can look at me,” he said, showing off an assortment of scratches, bruises, and scars. “After every game, I look like this. I take a beating.”

In the game against the feisty, young Spirits of St. Louis last April, Gilmore took a hard right to the chops delivered by Spirits’ rookie Maurice Lucas, an ABA instant replay of the Abdul-Jabbar-Awtrey bout. “That Lucas is mean in the middle,” said Virginia veteran Willie Wise admiringly after his first game against St. Louis.

It’s a dog-bites-man story when a rookie belts a veteran. Usually, it’s the other way around. Moses Malone, Utah’s wunderkind and the first player ever to go directly to the pros from high school, must have thought he was in the NFL instead of the ABA on occasion during his rookie season last year. “They’re knocking the hell out of that kid,” said veteran Utah forward Gerald Govan. “”Everybody’s trying to rough him up. But he’s standing up well.”

Malone was given survival lessons by his teammates. “A lot of teams have been belting him around,” said Roger Brown before one midseason tag-team match last year. “Against Memphis the other night, they were shoving him out of bounds. I asked him tonight, ‘Are you anticipating the hit? You can brace your body, but keep your hands loose.’”

Against the Pacers, it’s wise to keep everything loose. That goes for veterans as well as rookies. Says Indiana coach Bob Leonard: “There’s only one way to play this game—and that’s mean. If you’re going to be a handshaker before the game and be a nice guy, you’re going to get your head bashed in.”

Skinny St. Louis rookie forward Fly Williams got a taste of some of the ABA’s premier bashers and quickly decided discretion was the better part of valor. He chose to switch to guard. “Those big forwards are beating me up,” said the ever-smiling Fly. “I’m like one of those Black quarterbacks who comes to the pros and gets turned into a split end.”

Why doesn’t the ABA commissioner step in and do something to curb the tough guys? Well, for one thing, not long ago the commissioner himself was one of those bad dudes who would have swatted the Fly without a second thought had they been matched on the court. Dave DeBusschere had a reputation for being one of the game’s all-time tough defenders, and his former opponents had the lumps to prove it. He was not known as Dave. “De-Butcher” in Boston for nothing.

Houston forward Rudy Tomjanovich gazed in a mirror at New York’s Kennedy Airport after his final encounter with DeBusschere at the end of the 1973-74 season. Portland’s Rick Roberson had decorated Tomjanovich’s face with a twisted nose and two black eyes earlier in the season. “Now, just when I’m getting my looks back, I have to run into DeBusschere,” moaned the racked-up Rocket. “The nose is straightening out, and the black eyes are going away, then along comes DeBusschere. Now I’m dying from a hip pointer and a pulled abdominal muscle.”