[Another article without a need for a heavy windup. The headline says it all. At the keyboard is the fantastic Joe Gergen, who spent decades covering the big games and writing clean copy for UPI and Newsday. Gergen crafted this article for Zander Hollander’s The Complete Handbook of Pro Basketball, 1985. Again, props to Gergen and all hail to Bernard King.]

****

Those were the days, my friend. There wasn’t a tougher or more prized ticket in New York, on or off Broadway. In a town where it is widely assumed that the chic will inherit the earth, celebrities flocked to Madison Square Garden for a glimpse of the Knicks.

Woody Allen was a regular. So, too, was Dustin Hoffman. Robert Redford dropped by whenever he traveled East. The best-and-the-brightest entertainers inhabited the courtside seats, less

famous customers dressed as if attending the Metropolitan Opera, and the energy level in the building, if harnessed, could have charged all the skyscrapers on the isle of Manhattan.

The Jets’ hold on the city was as brief as a Joe Namath affair. And the Mets’ magic lasted through one memorable season. Later, with the help of George Steinbrenner’s manic drive to win, the Yankees would become the toast of the town. But in the early 1970s, only one team could be said to own New York. The Knicks not only played The City Game, but they played it with extraordinary skill and a special elan.

At cocktail parties and gallery openings, people exchanged sightings of The Open Man as if he had a face, a name, and an American Express Card. The favorite chant at the arena became so closely identified with the Knicks that, several years later, as Bill Bradley walked to the podium to deliver a commencement address, college students began shouting, “Dee-fense, dee-fense.” It was a heady time for basketball in New York, and a lesson to anyone who harbored ambitions in the sport.

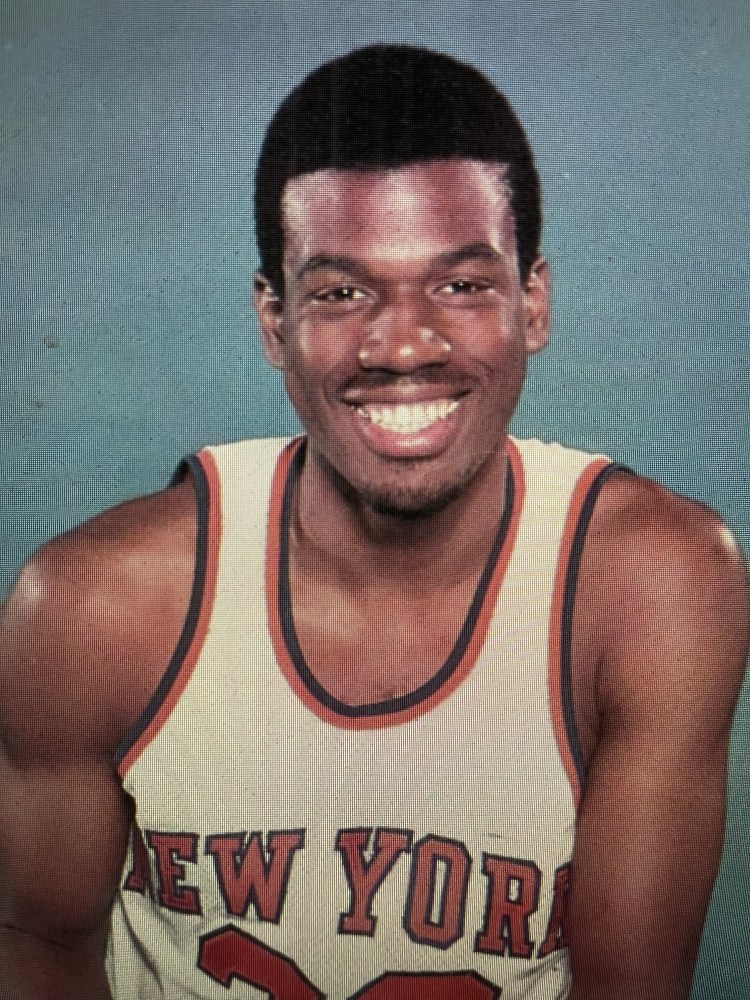

One such man was growing up tall and strong in the tough Fort Greene section of Brooklyn. Although the Garden was only a subway ride away, it was another world. And tickets were not only difficult to obtain but expensive. However, Bernard King had his dreams and his heroes. In high school, he asked to wear uniform No. 22 in honor of Dave DeBusschere, the Knicks’ all-star forward.

And then one day, King was invited to the Garden and introduced to the crowd as a member of the all-city high school basketball team selected by a New York newspaper. Part of his reward was a ticket in the blue seats, the mezzanine up near the ceiling. The Knicks overhauled the Bullets that night, and King marveled at the sights and sounds of the famous arena on basketball night.

King went off to the University of Tennessee the following year, and the sound was stilled. As the older players who had achieved two National Basketball Association championships in four years retired, management embarked on a disastrous open checkbook approach to rebuilding. The Knicks signed every available player with marquee value, including Spencer Haywood, Bob McAdoo, and George McGinnis (whose NBA rights, it developed, belonged to Philadelphia), without any consideration for how they would fit into a team concept. They even chased Wilt Chamberlain from coast to coast.

New York found another game. The Garden sat half-empty on basketball nights. The celebrities stayed away. That’s the way it remained for the better part of a decade. Until the spring of 1982. Until that kid from Fort Greene who had worshiped at the shrine some 10 years earlier, attracted a city’s curiosity.

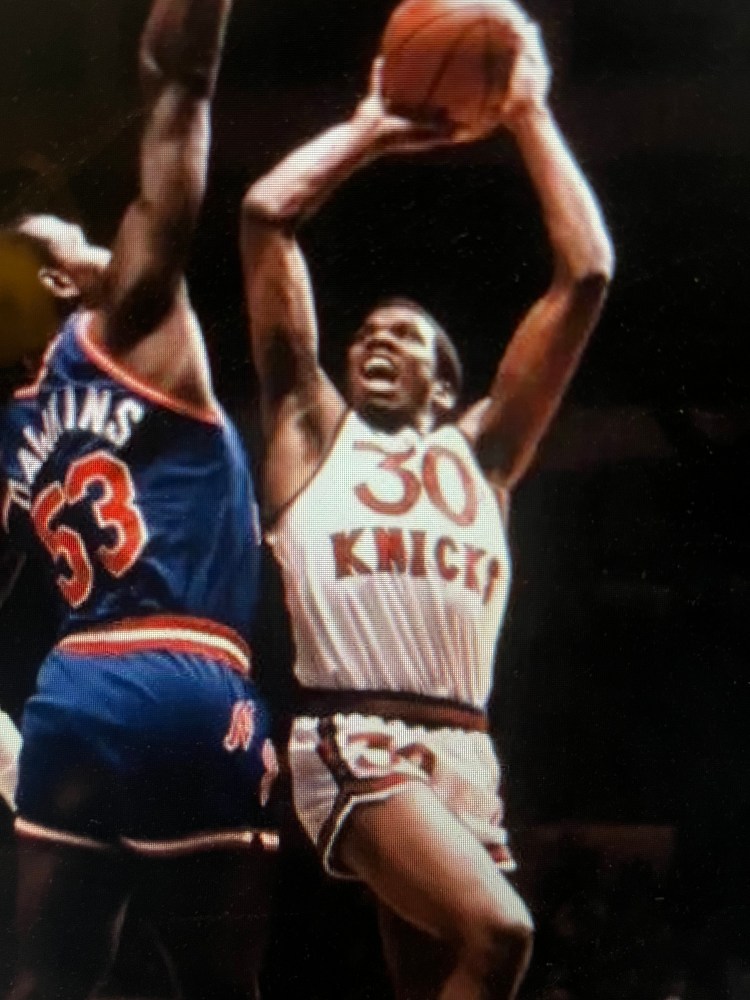

On consecutive midwinter nights in San Antonio and Dallas, the 6-feet-7 King scored 50 points. The stars came for a closer look. Allen, Elliot Gould, Peter Falk, Pearl Bailey. The Garden became semi-fashionable again. In the first round of the playoffs, against the Detroit Pistons, the man stood up and demanded attention. He scored 36, 46, 46, 41, and 44 points, an unprecedented string of accomplishments in the postseason period, as the Knicks struggled to a five-game series victory. That set the stage for the night of May 4, 1984.

It marked the first home game of the second round of the playoffs. The Knicks hadn’t won a second-round playoff game in 10 years, and they already had lost the first two games of the series in Boston. But the opponents were the hated Celtics, and the Knicks had King. The crowd at the Garden was at full throat 15 minutes before tipoff.

“I feel the history,” King acknowledged. “I feel excited being part of it. It’s a joy. It’s exciting to be driving to the games. There’s something special about this for me. To me, when you think about the NBA, you think about the Garden.”

King was decked out for the occasion in uniform No. 30. The Knicks had long since retired DeBusschere’s No. 22. Ironically, it was DeBusschere who, in one of his first actions as the new director of basketball operations for the Knicks, initiated the trade which brought King home from Golden State on the eve of the 1982-83 season. “I told Mr. DeBusschere I wanted to take his No. 22 down from the rafters and wear it,” King recalled. “He just smiled.”

And DeBusschere smiled again from a seat above courtside last May as King led the Knicks to a 100-92 victory over the Celtics. They were a team worthy of respect. Two days later, in a nationally televised Sunday afternoon game, the Knicks won again, 118-113, as King scored 43 against physical defenders Kevin McHale and Cedric Maxwell, who had publicly vowed he had enjoyed his last 40-point game of the season. “I expected to rip off his shirt,” McHale said in wonder, “and find a big S.”

The great forward would score more than 40 points (44) one more time in the series, and the Knicks would take the Celtics to a seventh game before Larry Bird asserted himself. The full measure of that accomplishment wouldn’t be felt for another month, until the Celtics completed their climb to a record 15th NBA title by overcoming the Los Angeles Lakers in the playoff finals. King, with a dislocated middle finger on each hand, had almost derailed the Celtics singlehandedly.

In the summer of 1982, Italian basketball officials sought NBA players and coaches for a national clinic in a resort town south of Milan. King spent a week at the camp, then took a tour of the country with his wife, Collette. He was enchanted.

A year ago, he went back. On that occasion, said Bill Pollak, his attorney and adviser, “I set him up with a car and said, ‘Don’t tell me where you’re going. Get lost.’” King did as requested, developing a great appetite for Italian cooking in the bargain.

For his third engagement this past summer, he was accompanied, not only by his wife, but his brother Albert and his wife. Albert happens to play forward for the New Jersey Nets and their relationship, hindered by an age difference which placed them in separate basketball orbits, has blossomed since Bernard’s homecoming. The two men live in adjoining towns in northern New Jersey and have struck a rivalry on the tennis court. King has not pursued fame nor rushed to capitalize on the finest season of his career. He limited his public appearances, which included a shooting session with Mayor Ed Koch to publicize the Big Apple Mobil Games for New York youngsters. He prefers to do what he can on an individual basis, and the Knicks acknowledge that his charitable work is a secret even to them. No spotlights, thank you.

Others speak of his fondness for poetry, the most contemplative of pleasures, but not King. On the road, he lives a room-service existence, preserving every bit of energy for the game he plays at maximum intensity. The scowl he wears on court is more than a mask. It is an attitude.

“Bernard is a like a light switch,” observed Ernie Grunfeld, who has known King since high school and played alongside him at Tennessee as well as with the Knicks. “Throw the switch; one second it’s off, and the next it’s at 100 percent efficiency.”

Basketball is serious business to Bernard King. It has not only been his career, but his salvation. “It’s the way I am,” he said during the playoffs last spring. “Isiah [Thomas] and Magic [Johnson], they smile all the time. That’s the way they play best. I set into the scowl. If I was smiling, I would miss half my shots.”

The look and the manner are virtually impenetrable. King doesn’t invite conversation from other players in the course of a game, and he volunteers little himself. Bumps and elbows and even occasional manhandling elicit no special reaction. But names can and do hurt him.

Against the Pistons, late in the second game of the playoffs at the Silverdome, the Knicks were huddling around Coach Hubie Brown when a heckler succeeded in getting under King’s uniform. “Isn’t it time you had a drink?” the man yelled. King started for the heckler, but was restrained. Afterwards, despite a 46-point performance in the defeat, King declined not only to discuss the incident but even details of the game.

He regained his composure the following day, but the obnoxious fan had picked at scar tissue. For now, King’s past is a closed issue. The man has declined offers from book publishers and motion picture producers. He has turned down first-person magazine articles and television interviews which would broach the subject. He has bottled it up inside.

King was an alcoholic. The only reason he’s still playing basketball is that he admitted to the problem in 1980. A series of arrests—starting in college, proceeding to his rookie pro season with the Nets and culminating in charges of sexual abuse brought by a woman in Salt Lake City while he was with the Utah Jazz—finally led him to a rehabilitation center and membership in Alcoholics Anonymous. “I was saving my own life,” King said in the early months of treatment. “There’s nothing more rewarding than that.

“I’d had a premonition for almost two years that I was going to die young. I was living very dangerously in the sense that I’d drive with a quart of alcohol in my system. I’d get in the car to drive home, and I wouldn’t remember the ride.” On one such occasion, in his second NBA season with the Nets, he was found slumped over the wheel while his car sat in the middle of a Brooklyn intersection at five in the morning.

He started drinking, he said, as a social outlet in college, which was no place like home. The habit grew once he turned professional. “I was very unhappy my first year in the league,” he said. “I’d have great games, score 30, 35 points and go home to an empty apartment. There was no one around to share the joy with.”

The loneliness grew even more unbearable when the New Jersey Nets, his first pro team, decided he was beyond help and shipped him to Utah, a Mormon abode with a tight social framework, and few Blacks. Although he started his rehabilitation process while with the Jazz, they, too, despaired of him and sent him to Golden State. It was in the Bay Area where King reclaimed his life and his talents, marrying a special-education teacher, establishing a home, and growing into an all-star. He played two seasons for the Warriors and, upon departing for New York, took out newspaper ads in Oakland and San Francisco to express his feelings: “To Bay Area fans. With gratitude and appreciation for your support. Thanks for the memories—Bernard King.”

****

Despite the two championship teams in the early 1970s, the Knicks have never had a player of King’s ability. They were a total unit in their best seasons, five spokes in a wheel. The current Knicks, because of their own inadequacies and his remarkable presence, revolve around King. “He is,” said Red Holzman, the coach of the great Knick teams and now an advisor to the club, ”the greatest scoring machine I’ve ever seen.”

In the Knicks’ 180 playoff games prior to the meeting with the Pistons, only three players had scored 40 or more points—Cazzie Russell in 1968, Willis Reed in 1969, and King in 1983. In the next five games, with survival riding on the outcome, King topped 40 four times. “Not even Oscar Robertson, with all his greatness, ever dominated a team like Bernard,” said Eddie Donovan, the Knicks’ general manager in the glory years. “Once he gets out in the open floor, there’s no stopping him.”

“I’ve never seen any one player dominate a team like King has the Pistons this season,” said Dave Bing, once a backcourt star in Detroit and now a team broadcaster. “He’s just one great talent, and there is really no way to stop him. His release is so quick that before you can even double-team him, his shot is in the air.”

Although he often gives away a couple of inches to defenders, King likes to position himself down, low, take a pass, and hit a whirling baseline jump shot. Half the time, it appears, he doesn’t see the basket before he shoots. That’s because half the time King relies on his feel for the basket. “I got the ball in the positions where I like to set it,” he said after his 50-point performance against San Antonio, “and I felt all the seams. What I mean by that is that you don’t always have to look to see where the defense is, you just feel it and go.”

King is at his creative best on the fastbreak, but Coach Hubie Brown prefers a half-court game with set plays. The forward simply does his best within the system. “There are not enough adjectives to talk about Bernard King,” Brown said. Suffice it to say that Brown appointed King captain for his dedication.

“People ask me where Bernard would play on those old teams,” Holzman said, “and my only answer is, for a guy like that, you could always find a place. What impresses me is how he shoots with such quickness and accuracy. Other teams overplay him, they try to deny him the ball, they double-team him and triple-team him. But he keeps scoring.”

And he keeps improving. King has made a point each summer of going back to camp. After his vacation in Europe, he spent 10 days working on his game with Pete Newell at Loyola Marymount College in Los Angeles. He has always played with determination and intensity. But he continues to challenge his potential, even after being selected the NBA’s Player of the Year by The Sporting News in a vote of league players.

His work habits, according to Brown, are the best he has ever seen. And that’s fitting. When King returned to New York from personal and professional exile, he went to DeBusschere and told him he always wanted to be No. 22. “I emulate him,” King said. “The way he worked, that’s one of the things I like to think we have in common.”

But DeBusschere, for all his effort, didn’t have King’s gift with the basketball. King and Bird, according to DeBusschere, “play on a different level. They have incredible talent.”

To think King’s great talent almost was wasted. Certainly, the man thought about that himself as he wrestled with alcohol four years ago. “I know and realize now that I’m fortunate,” he said at the time. “Fortunate that I wasn’t arrested more in an automobile. Fortunate that I didn’t kill anyone, and that nobody killed me. I honestly believe that I should not be here, that I should have been gone long ago.

“But I think that God has left me here long enough to realize that I had a problem and that I had to deal with that problem. In terms of my career, I think this is my last opportunity, my last chance. But if I ever start indulging again, I won’t have any chance. And so, I can live if I want to live. I can play if I want to play. I’ve been given the chance to do that.”

He has succeeded with that final chance, succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations. King has forged a good life for himself back home and, in the process, given New York basketball the transfusion it desperately needed.