[Before starting From Way Downtown, I knew of Sam Goldaper from his days at the New York Times and later stumbling over his byline in several basketball magazines. But I never appreciated just how prolific of a basketball writer he was during the 1960s and into the next decade. While the structure and style of his stories can be a choppy in places, they always make some interesting points. That’s the case in this article from the magazine Complete Sports’ Special Pro Basketball Issue, March 1969. The topic, spelled out in the headline, should be a very familiar one.]

****

On Saturday, November 7, 1959, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson accepted a speaking engagement for a non-political dinner in Brooklyn. In the week’s top collegiate football contest, Syracuse University was a six-point favorite over Penn State. Sam Snead’s key putt helped the United States take the Ryder Cup lead over Britain, and the National Basketball Association was still struggling for acceptance.

In Boston, it rained hard that day, but it was to have no effect on the attendance at the Boston Garden for a game between the Celtics and the Philadelphia Warriors. The game had been a sellout for months.

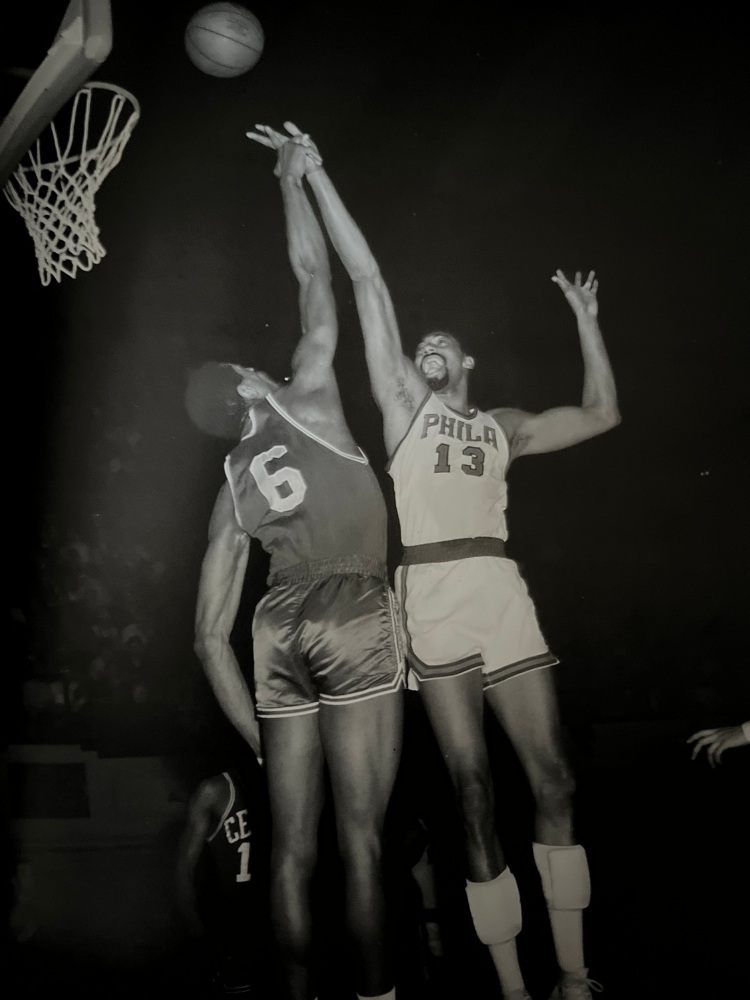

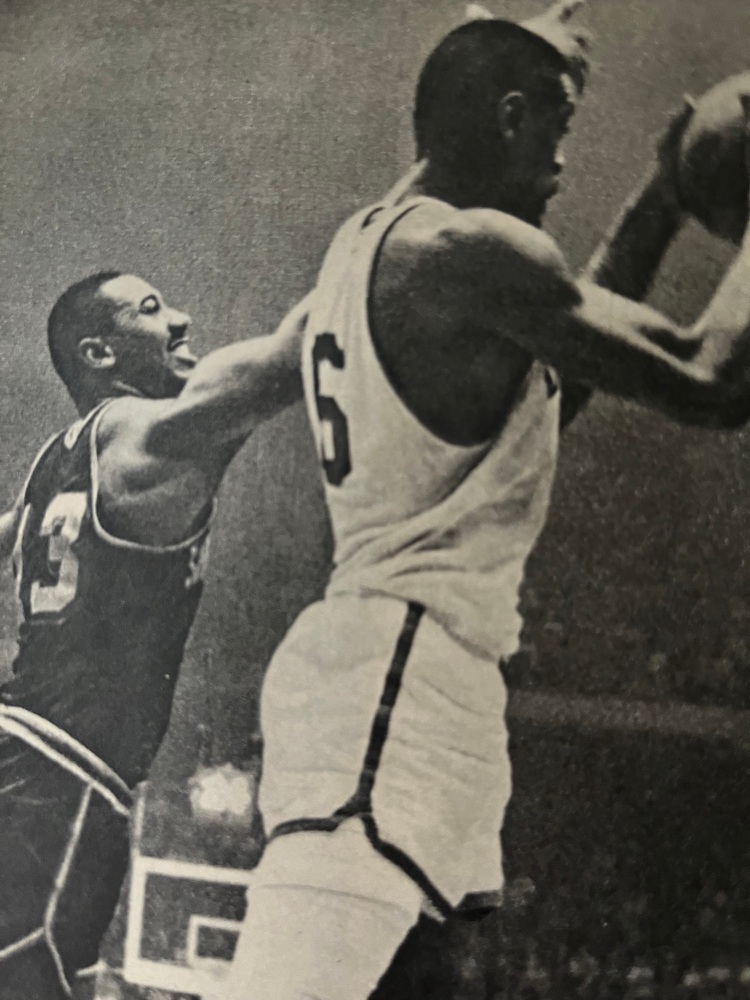

It was the first meeting between Bill Russell of the Celtics, who had come into the NBA two years before to start Boston on a dynasty unparalleled in sports history, and a 21-year-old rookie named Wilt Chamberlain. Wilt had already owned more luxury items than most athletes could afford in a lifetime. From an estimated salary of $75,000 he had earned touring with the Harlem Globetrotters, Chamberlain had purchased a 13-room house, a white Cadillac convertible, and a three-year-old colt named Spooky Cadet.

By the time the teams had arrived at the Boston Garden, all but a few seats were filled. When the players came out to take their warmups, spectators surrounded the far end of the court to watch Chamberlain, all 85 inches of him, take his awesome, patented dunk shots, and watch Russell’s less spectacular push shots and hooks. Russell would carry the tag of Mr. Defense, while Chamberlain would be the most devastating force ever connected with the game of basketball.

Aware that this was one of the great moments in sports, the two centers stopped shooting and met briefly at center court. Chamberlain joked easily, destroying the image of a nervous rookie about to do battle with an established star. Russell remained serious during the entire meeting.

The next day, the New York Times carried, in part, this report of the meeting:

“Bill Russell, and Wilt Chamberlain played each other to a standstill last night. Boston had the best of the rest, and the Celtics scored their sixth-straight NBA victory, 115-106, over the Philadelphia Warriors. It was Philadelphia’s first loss in league play, they had won three games. Chamberlain and Russell played the entire 48 minutes and appeared to be tiring badly in the late stages.

“Chamberlain outscored Russell, 30-22, but it was his lowest point production of the season. Russell, at 6-feet-10 and the acknowledged defensive standout of the league, outrebounded Chamberlain, 35–30. In all, their performances were about even, with Wilt showing better on offense and Russell better on defense.”

That was the story of their first confrontation, and, in the decade that has followed, every time the two friendly enemies meet, they write another chapter in the ageless struggle of defense versus offense.

Chamberlain averaged 37.6 points in his rookie season. But against Bill Russell and company, it was 39 points. Russell, however, clamped down during the NBA playoffs and held Wilt to 30.5 points. Wilt once scored 62 points against Russell (January 14, 1962, a court record for the Boston Garden). On another occasion, Bill held Wilt to two points and no field goals during a 20-minute span.

During the 1961-62 season, Wilt also scored 100 points against the New York Knickerbockers and wound up with a record all-time 50.4 scoring average. During the playoffs, Russell chopped him down to 36.6 against Boston, and the following year checked him with 29.1 for the season and 29.2 during the playoffs.

So it has been down through the years, except that last season was just a bit different. The Celtics completed one of the great upsets when they dethroned, devalued, and dispirited the Philadelphia 76ers. The 76ers were supposed to be a coming dynasty, with youth and power. The Celtics were an old empire that had seen its glory days and was now supposed to be on the decline.

After the final game in the Eastern Division playoff, Larry Merchant wrote in the New York Post:

“And Chamberlain with dramatic correctness, stood out in the finale for not standing out. He scored only 14 points—and took just one shot in the second half. Never mind his 34 rebounds. Never mind the crippling injuries that turned the 76ers in basket cases instead of shooters. Never mind the super defense played by an aroused Bill Russell. Wilt Chamberlain took one shot in the second half, which says it all.”

The Russell-Chamberlain rivalry spilled over the basketball court to the fans, players, and coaches. It even had an effect on the salary negotiations of Russell, the immovable defender, and Wilt, the irresistible scorer.

During their entire career, since the first meeting, the controversy has raged and questions asked, “Wilt or Russell—who has the edge?” Actually, answering that question posed still others, most of them takeoffs on age-old clichés, such as “the best offense is a good defense” and “you can’t win without scoring.”

Two seasons ago when Philadelphia won the NBA championship, it snapped at the number of titles the Celtics put together like a string of pearls. Alex Hannum, the Philly coach, called his team the greatest in the history of pro basketball.

With that remark came a rebottle from the Celtic dynasty, and it, of course involved Russell versus Chamberlain. “I wouldn’t expect Hannum to say anything else,” said Russell, the Celtic coach. “I’d say the same thing if I were their coach, but we had teams which would have beaten them. Our 1960–61 team, for instance, that was a pretty good team.”

In the discussion that followed, Red Auerbach, who turned over the Celtic coaching reins to Russell for the general manager’s job, got into the act. “Hannum,” said Auerbach, “did a terrific job with that team.”

“Wilt,” interjected Russell, “did everything.”

“If he did it three or four years ago when Russell was younger,” fired back Auerbach, ”it would have been more emphatic, but Chamberlain didn’t do it alone. They all did it. Hal Greer did a fantastic job. They had fantastic power with Luke Jackson, and they got a single game. I never saw him play that well in consecutive games, even in other playoffs. He realized he could be a great man and part of the team.”

That was quite a compliment for Wilt, especially coming from Auerbach, who has not been one of Chamberlain’s great fans through the years. In fact, in Red’s book Winning the Hard Way, written by Paul Sann, the executive editor of the New York Post, Auerbach is quoted as saying, “Chamberlain never joined the team. It was the other way around for Russell.”

But if Auerbach finally decided to throw Chamberlain a compliment, it hasn’t been the same for Russell and Chamberlain. They have remained respected enemies on the basketball floor and friends off it.

Russell once explained Wilt better than anyone else. “Chamberlain’s attitude has not been as bad as people have thought,” said Bill. “When he first came into the league, he had a different concept of the game than I had. Now his is the same as mine. He’s been playing the way I played for the last 10 years. He did it better than I used to do it, but it’s the same game—passing off, coming out to set up screens, picking up guys outside, and sacrificing for team play.”

Chamberlain and Russell have had varying careers on and off the court. People have been continuously asking that Wilt prove it, although he has been the most devastating individual force in the NBA. Actually, Wilt is a man driven to accomplishments and a believer that nothing is beyond his grasp. He has met every challenge pro basketball has had to offer and succeeded.

When he was called just a scorer, he turned and became a feeder. When the second guessers said he couldn’t block shots like Russell, he proved that he could. He was the first center in NBA history to lead the league in assists with 702 last season. Before the season started, he had played in 706 games without fouling out, and in nine years had piled up to 25,434 points.

“He can do anything in basketball,” once said Hannum, who coached him in San Francisco and later in Philadelphia. “He’s the greatest player who has ever played. ”Yet, when he doesn’t measure up in some games to those standards, the paying customers feel cheated.

On the other hand, Russell has become an accepted national institution on the court and a controversial figure off it. He once was reported as saying, “I owe the public nothing, and I’ll pay them nothing. I refuse to smile and be nice to kiddies.”

Last season, Clif Keane wrote in the Boston Globe, “Back a few years ago, everyone in the league said that the day Bill Russell started to fade, forget the Celtics. They claimed they never worried about the Couys or Heinsohns or Sharmans. Take Russell off the court, and it’s goodbye.”

Keane wrote that in his column on January 9, 1968, when he also interjected, “The great man is shadow boxing on the court. He used to jump like a pogo stick. Nowadays, it would be difficult getting a four-page paper under the sneakers when Bill leaps.”

Toward the end of the column, he also wrote, “But Auerbach, like everyone else who has seen the Celtics over the years, knows that nobody can help the team enough to win this whole business in March and April like Russell.”

He was so right. Last April, the 34-year-old Russell led the Celtics to their 10th NBA championship since joining them following the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. In 1965, Russell publicly stipulated that he received one dollar more on his three-year contract than the $125,000 that Chamberlain was reported to be earning. It’s been that way all along—controversy.

Russell or Chamberlain? How do you like your steak—rare, medium, or well done?