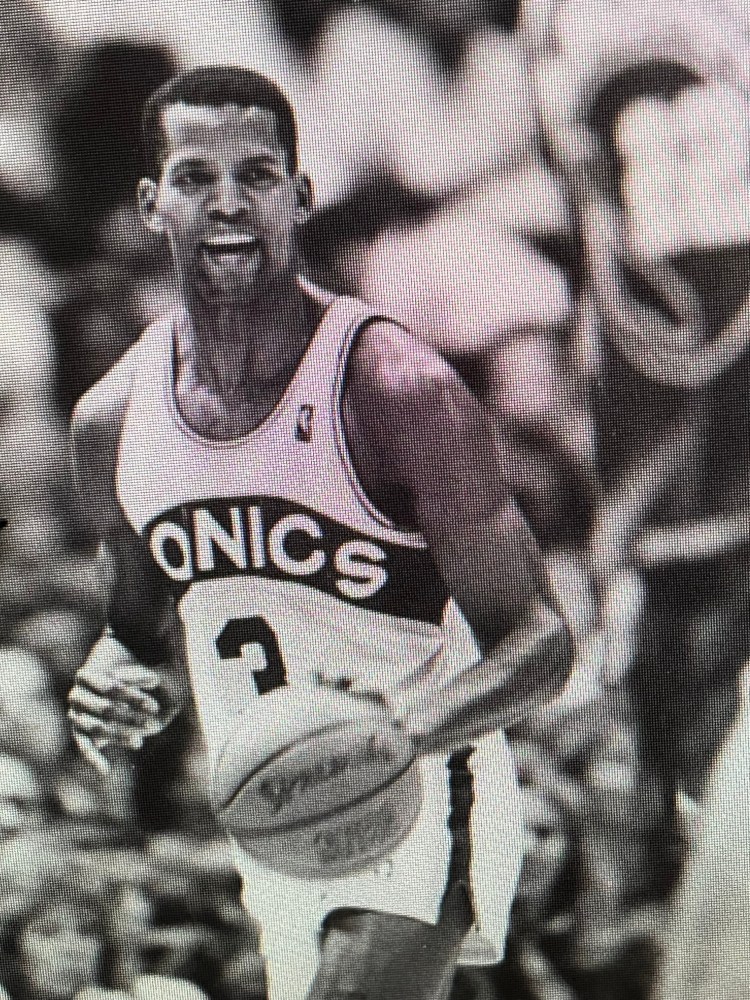

[Dale Ellis had his way ups and way downs during his long NBA career. But when he was way up, there were few in his class stroking it from long range. In this article, published in the 1989 Street & Smith’s Pro Basketball annual, writer Fran Blinebury tells the story of Ellis stroking it from afar for Seattle. As a quick sidenote, I’ll run a longer, more-detailed profile of Ellis a little later.]

****

Pro basketball is a sport known for its seemingly effortless scoring and its ballet-like grace. But there are times when it appears to degenerate into something resembling hand-to-hand combat. Or maybe elbow-to-face fighting.

There are times, particularly as the playoffs roll around, when the skills for dribbling, cutting, and putting the ball into the basket, look like they’ve taken a backseat to the more macho aspects of the game, such as blocking, tackling, and bone-breaking.

You could ask Dale Ellis, who picked up a broken nose for his troubles last spring while his Seattle SuperSonics were battling—literally—to get past the Houston Rockets in the playoffs. The irony, of course, is that a player who embodies the term “finesse” is the one who should have his cartilage shattered. But then another irony is that in the push-and-shove series that might have been more suited to the World Wrestling Federation than the National Basketball Association, the one player who constantly showed his strength was this will-o’-the-wisp Ellis, who is just a shooter. Which is like saying that Hemingway was just a writer. Or Michelangelo was just another ceiling paint. Or, as John Wooden would say, “Caruso could just sing.”

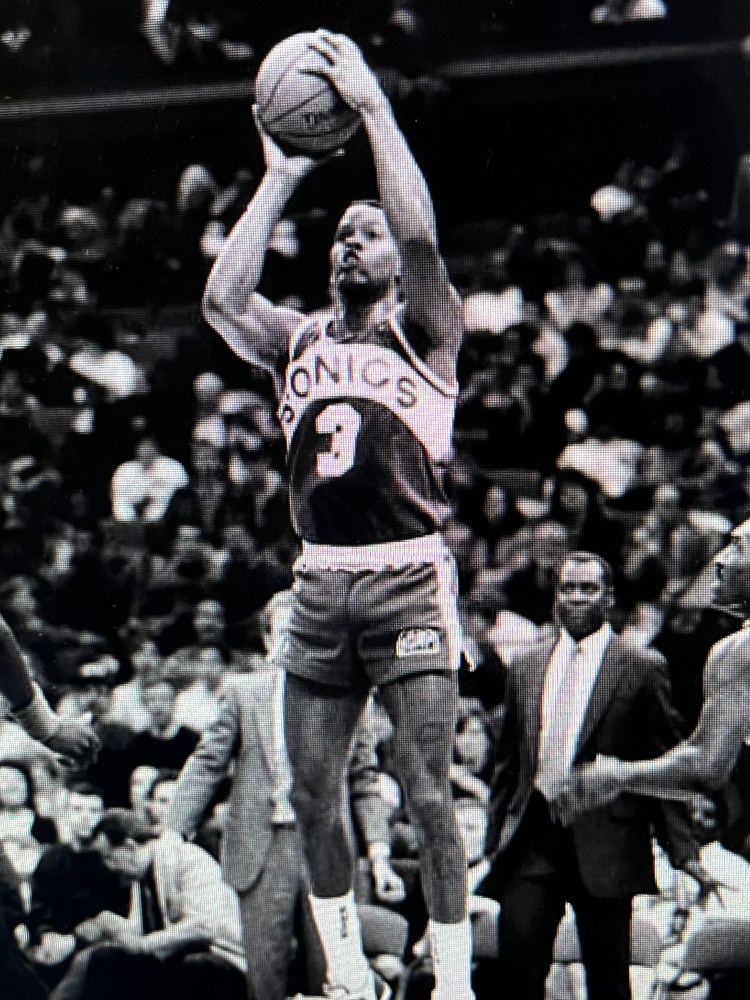

The fact is that Ellis is the closest thing to a shooting machine in the game today. He runs off double- and triple-screens that everybody in the building knows the Sonics are going to set for him to bury jumpers, yet everybody is helpless to stop him. He’ll pull up on a fastbreak to stab in an 18-footer like it was a layup, and he’ll break your heart with a three-pointer with a hand in his face to stop your momentum cold.

“Dale is our most-consistent player, night in and night out,” says Sonics coach Bernie Bickerstaff. “He’s so good that when he does occasionally have an off-night, it throws you. You just don’t expect it.”

That’s because for the previous three seasons, Ellis has ranked among the NBA’s top guns. Last season, he fired in points at the rate of 27.5 a game, which ranked third in the league behind only Michael Jordan and Karl Malone. Yet he still might be one of the most-unheralded stars in the game.

Perhaps that’s because Ellis got a late jump on his stardom. In fact, there was a time when many wondered if Ellis had what it takes to be a big-time player. That’s because he barely got any big minutes while becoming a mainstay on the end of the Dallas Mavericks’ bench. Ellis was a victim of circumstances. As it turned out, the worst of circumstances.

When he finished his career at the University of Tennessee as a 6-feet-7 shooter who had played every position from guard to center in college, he was a player whose stock few could evaluate accurately. The Houston Rockets were considering making him the No.3 pick in the 1983 college draft and have been kicking themselves ever since for not doing it. The Rockets took Rodney McCray instead, and then Ellis wound up as the No. 9 choice on the first round and headed to Dallas.

The problem was that the Mavs were already stocked at the small forward and big guard positions with Mark Aguirre and Rolando Blackman, and Ellis simply began a long and frustrating tour of duty as a practice player and a bench jockey.

“I’d daydream sometimes on the bench at Dallas and think about what I could do if I only got to play,” says Ellis. “Then a whistle would blow or something, and then I realized that I was just watching another game. Never did I think I would be like this.”

This has been his past three seasons with the Sonics, where Ellis has established his reputation as a scorer who can consistently carry the load for his club. This has been his ascendency to the level of an NBA Western Conference all-star. This has been his rise to the top of pro basketball’s shooters as he captured the 1989 Long Distance Shootout during the NBA All-Star Weekend in Houston.

In the first year that Ellis went from Dallas to Seattle, he won the NBA’s Most Improved Player Award. Of course, that was not too difficult to do for a player of his ability when you consider that his playing time went from 16 minutes to more than 36 minutes a game.

Ellis teamed up with Tom Chambers and Xavier McDaniel to give the Sonics a trio of players who averaged more than 20 points a game for both the 1986-87 and 1987-88 seasons. When free agent Chambers moved on to Phoenix for the 1988–89 campaign, the Sonics barely skipped a beat. Ellis simply bored down and moved his game up another notch. What’s more, his ballhandling has improved, and he no longer feels uncomfortable in the Seattle backcourt. It is those who have to guard him who are uncomfortable.

“He’s almost automatic if you give him a half-step to get the shot off,” says Houston’s Mike Woodson, who attempted to dog Ellis all through the playoffs. “You’ve got to stay right up in his face, try to bump him off stride. But even then, he can still hit the shot. Your best chance with Dale is to not let him get the ball in the first place.”

Or maybe to smash him in the nose.

Actually, Ellis’ fracture came compliments of his own teammate, Olden Polynice, during a battle for a rebound. Ellis came out for Game 3 of the series wearing a face mask. But he missed a couple of jumpers, said it was a distraction, and did away with the nose guard for Game 4. That’s when Ellis, broken beak and all, pumped in 26 points and led the Sonics to the series win.

That toughness has been part of Ellis’ development into a legitimate star. When he takes the court now, it is with his square-cut jaw set firmly, his bright and always alert eyes taking aim on the basket.

Bickerstaff says there are two things he likes about Ellis, besides obvious skills. “Dale is a guy who never steps back from anything,” says the coach. “He is willing to step right up and accept any challenge you give him. Secondly, Dale leads by example. He’s one of those veterans who brings his lunch pail to work.”

“All I want to do now is prove to myself that I can be one of the best in this game,” he says.

After a late start, Dale Ellis has already convinced most of the rest of us.