[If you grew up watching the 1980s NBA, there’s no forgetting Michael Cooper and his Coop-A-Loop dunks. He went up as high as anybody to retrieve the good, the bad, the ugly lob then harpooned the ball through the hoop. Nobody did it any better.

What follows are two articles from his Cooper’s early years with the Lakers. The stories are a little out of chronological order, and that’s because the first one sets up his bio a little better than the longer second profile. Between the two, though, you’ll get a nice blast of the Michael Cooper past. For me, Cooper is one of the greatest sixth men of all-time. He was just such a difference maker with his suffocating defense, his accurate one-handers, and his amazing alley-oop dunks.

The first story, pulled from the March 1982 issue of Hoop Magazine, comes from the veteran Southern California sports scribe, Mitch Chortkoff. He knew the Lakers inside and out.]

****

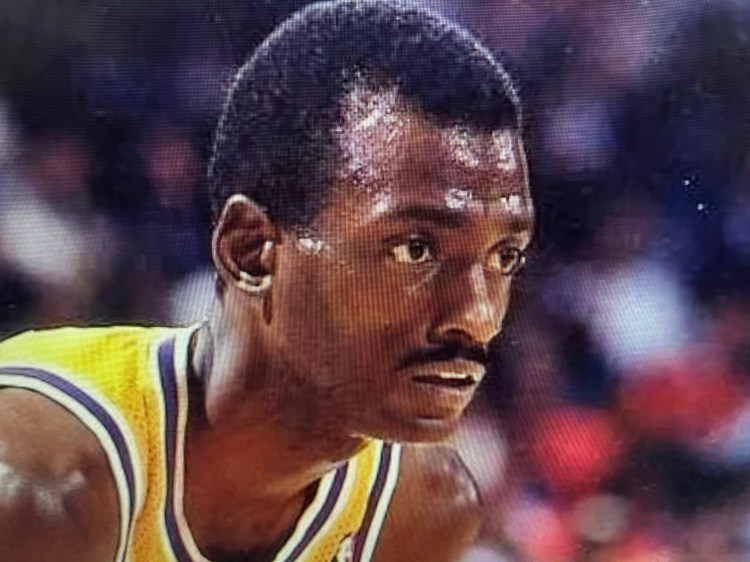

Michael Cooper of the Los Angeles Lakers might be the best dunker in the NBA. Certainly, he’s a candidate with his acrobatic trips through mid-air and jams which seem to defy gravity. That’s pretty good for a guy who once was told by doctors he might never walk again. He serves as an example—never give up!

Cooper’s left leg was torn apart when severed by the jagged edge of a coffee can as a youth in Pasadena, Cal. It was ugly, but he can recall the details.

“My uncle had these puppies, and I went out in the yard to play with them,” he remembers. “I slipped and landed right on the cut-off edge of the coffee can. It cut up everything. Muscle, ligaments, the works. I had 100 stitches, and they did say I’d probably never walk again.

“I was six or seven years, old, and I had to wear a knee brace after that. The other kids would be out playing, and I could only watch.

“One day when I was about 13, I just took off the brace. I just couldn’t stand it anymore. I also started running. I ran everywhere—to the store, on the sidewalks, even out to get the paper in the morning. I guess I’m lucky it happened when I was young, and I could grow out of it.

“My grandmother watched me closely. If I got hurt, she’d make sure it was nothing serious.”

Cooper went to Pasadena High, a perennial Southern California basketball powerhouse under coach George Terzian. There, he worked with a weight machine to strengthen the leg. “The kneecap would slide out,” he recalls, “but now I have absolutely no trouble with it. Really, it’s amazing. It never goes bad. I have no pain. It doesn’t stiffen up in bad weather.”

Former Lakers coach Paul Westhead says that Cooper never has stopped running. Used as a reserve, Cooper comes in and adds a dimension of speed and hustle to the game. “He was a key to our greyhound unit,” says the ex-coach. And Westhead backed up his word by often removing a big man and using the 6-feet-5 Cooper along with a small forward, two guards, and a center to outrun opponents.

The odds of any high school player ever making it all the way to the NBA are remote, but even fewer longshots like Cooper ever have succeeded. First, there was the handicap of the damaged leg. Then, the fact that he was cut from his high school team as a junior. Even as a 14-point per game scorer as a senior, he was not highly recruited by major colleges.

Cooper went to Pasadena City College, then earned a scholarship to the University of New Mexico, where he blossomed into a third-round pick in the NBA draft.

Again, adversity struck. While playing in the Southern California Summer League, Cooper suffered torn knee ligaments. He spent his first pro year on the injured list, then had to move past several other candidates the next year in training camp.

Jack McKinney was the Lakers head coach then, and he couldn’t help but notice how Cooper shut down anybody he defended. Now Cooper is recognized as a vital cog in the Lakers’ makeup, the holder of a multi-year contract. But it could have been so different, and he’s the first to realize it.

Cooper learned the value of hard work early, and perhaps that’s another reason for his success. Others with potential might not have pushed themselves so hard. The work habits continued into his pro career. Last summer, Cooper played with the Pasadena team in the pro league and did more work with weights.

One day, the skinny Cooper was seen heading for the weight room with rugged Mark Landsberger, a Lakers teammate who is more easily associated with weight training.

But Cooper said he had goals during the summer, first to stay in shape and second to improve his offensive moves.

Obviously, he did a few things right, as his team won the championship. Now he’s back in the more-structured NBA brand, and Cooper has a certain role to fulfill. “We have a good team, and I’m happy to do what’s expected of me,” he says.

One of those things is to make acrobatic dunks from the Lakers set offense. A pick is set for him near the free-throw line, and he soars toward the hoop, taking a pass above the rim, and jamming through.

Any NBA player would be proud. And it’s hard to believe the guy doing it once was in danger of not being able to walk.

[Up next is a May 7, 1980 profile of Cooper that I’ve gently edited in just a few places. The story, from the highly-regarded reporter Ted Green, ran in the Los Angeles Times during the 1980 playoffs under the headline: Upstairs, Downstairs with Michael Cooper. As this story and the one above attest, Michael Cooper was much-beloved in the Southland.]

In the Lakers’ season opener at San Diego, Michael Cooper took off and threw down a savage dunk that nearly left a “Wilson” imprint on Sidney Wicks’ face. To keep from crashing to the floor, Cooper had to hang onto the rim. The Lakers talked about the play for a week. Still do, from time to time.

Six months later, in the last regular-season game at the Forum, the Lakers tried what had become a patented play, an alley-oop pass over the rim to Cooper. Golden State’s Sonny Parker saw it coming and moved into the lane as Cooper started his leap. One of Cooper’s legs landed on Parker’s shoulder, and the Warriors’ forward actually carried Cooper some eight feet to the basket. Cooper caught the pass anyway and still dunked it.

“That was the best one,” Laker interim coach Paul Westhead said. “An eight-foot, piggyback ride, followed by a slam. The players flipped out. They monitor Coop’s plays, you know.”

Between the first and last league games, Michael Cooper spent more time in the air than some stewardesses and made enough spectacular plays to keep TV stations indefinitely stocked with spectacular replays.

Along the way, he leaped into the imaginations of Laker fans, who seem to view him as some kind of otherworldly combination of Julius Erving (king of the NBA hang gliders), David Thompson (the dunkingest guard), and Dennis Johnson (defensive ace). He has also amazed his teammates, who’ve given him nicknames like Scoop, Coop de Ville, and Sky Leaper, the one Cooper likes best.

But Cooper’s greatest leap—the most impressive of all—is from borderline Laker, the last of 11 players to win a job during camp, to invaluable sixth man whose two-way skills and volatile emotions helped change the club’s personality and round it into a potential champion.

Not many NBA players have made the quantum leap Cooper has when you consider the doctors said he’d never walk without a metal brace after a childhood accident left him with 100 stitches in his leg; that when the Lakers drafted him out of New Mexico on the third round in 1978 he had a reputation as a lazy defender and an out-to-lunch shooter; that he tore knee ligaments in that same left leg only seven minutes into his rookie season, and faced a long, hard, uncertain rehabilitation; and that up until the very end of training camp last fall, the Laker coaches weren’t quite sure who they’d cut last: Cooper or another big guard, Ron Carter.

Consider, too, that Earvin (Magic) Johnson, the Lakers’ rookie star who was something of a college basketball junkie, had never heard of Michael Cooper when he joined the club. Hadn’t heard of him, that is, until Cooper dunked on everybody in the summer league at Cal State L.A., then threw one down over Kenny Carr, a 6-feet-8 leaper, during camp.

“I said, ‘My goodness, who is this boy?’” Johnson said.

Here’s who: Cooper is the swingman who has contributed so substantially (and unexpectedly) to the Lakers’ heady season that the club has already redone his contract (originally $30,000) once to include bonuses and a loan, and they’re already talking to Cooper’s lawyer about improving it a second time after the playoffs. At $30,000, Cooper was pro basketball’s biggest bargain. Now he’s on his way to six figures.

Suddenly, in a league where Bobby Jones (Philadelphia), Fred Brown (Seattle), Junior Bridgeman (Milwaukee), and M.L. Carr (Boston) are continuing the sixth-man tradition started in Boston by Frank Ramsay in the 1950s and continued in the 1960s and 1970s by John Havlicek, the Lakers have one that compares with the best.

When Cooper, in effect finishing his rookie season (although, technically, it’s his second), gets a little more experience and maybe develops a jump shot off the dribble this summer, he may even compare favorably with those other gifted sixth men. And that’s saying something, since Brown and Bridgeman are prolific scorers, Carr is an important cog in the rejuvenated Celtics, and the 76ers’ Jones is not only the baddest white dude in the league (as Darryl Dawkins calls him), but a highly productive player at both ends of the floor.

Westhead, for one, thinks Cooper already compares favorably. “You think of a Junior Bridgeman scoring 20 points a game off the bench,” Westhead said. “Well, Michael Cooper gets 20 a game, too . . . the 10 he scores, and the 10 he takes away with his defense. In fact, using that formula, he might be a higher scorer than all the (other) sixth men.

“Coop shuts people down and also comes up with spectacular offensive plays, the igniting kind that give our team a tremendous psychological lift. This double specialty is rare in a bench guy. [indeed, it’s rare in anybody]. You usually don’t find that wrapped in the same body.”

Paradoxically, for such an electrifying player, Cooper has been little publicized, at least to this point, largely because there’s only so much publicity to spread among Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, Jamaal Wilkes, and Norm Nixon, Cooper’s more famous teammates. In a sense, Cooper is still an NBA trade secret, though he’ll be harder to hide after CBS [finishes covering the playoffs]. He says it’s enough, for the time being, that the Lakers recognize his value.

“It’s hard to place a value on any player,” Westhead said, “but I don’t think we could have won 60 games and gotten that crucial first-round (playoff) bye without Michael Cooper. He single-handedly won 12 games for us with his defense.

“Plus, the way Magic brought a new enthusiasm for basketball to the Lakers, Michael brought a new enthusiasm for defense. And it became contagious.”

Curiously, Cooper, who grew up with his grandmother in Altadena, was mainly a shooter and scorer at Pasadena High and Pasadena City College, where he used to go tooth and nail against another little known (at the time) local player, Dennis Johnson of Harbor College.

Cooper—who said he used to launch 20- and 25-footers, one after the other—was still a shooter until Norm Ellenberger got hold of him at the University of New Mexico. Ellenberger is gone after a scandal at the school, but Cooper said he taught him an appreciation for defense. By the time Cooper was a senior, his game had done a 180. He couldn’t wait to get back on defense. Offense was like a coffee-shop meal; he couldn’t wait to get it over with.

“Defense,” Cooper said in an interview, “became my big thrill.” And when he saw that defense, primarily, made his friend Dennis Johnson the Most Valuable Player in the NBA Finals a year ago, Cooper decided, at least subconsciously, that defense would be his specialty with the Lakers.

So, when Magic hurt a knee in the third game of the season, Cooper subsequently started in his place and put the clamps on Dennis Johnson and Pete Maravich, in succession. Once Cooper’s initial nervousness wore off and his natural talent took over, the Lakers decided that veteran guard Ron Boone was expendable, and they shipped him to Utah with unusual dispatch. By the playoffs, Seattle’s Dennis Johnson was saying that Cooper reminded him of himself.

Defense isn’t Cooper’s only thrill.

“Slamming is second,” he said. “When I was little and couldn’t slam on a 10-foot basket, I’d build my own little baskets, so I could make up all kinds of dunks. Now, up there over the rim, knowin’ you’re in the NBA, the thing you dreamed about, well, you feel kind of elite.”

Cooper said his favorite dunkers, for height and style, are Erving, David Thompson, George Gervin, and Darrell Griffith (“and he ain’t even in the league yet”). Cooper should be one of his own favorites, too, for he probably jumps as high as anyone his size. He can get his entire palm over the top of the square on the backboard above the rim.

“Coop is a 12 ½-footer,” Laker assistant coach Pat Riley said.

“Put down 12,” Cooper said.

The dunks, including some astounding one-handers wherein he has reached behind his head and far to the side to catch an offline alley-oop pass and still thrown it down, have made Cooper the Forum’s newest cult figure. The crowds chant, “Coop, Coop,” drawing out the oo’s so they sound like oooooo’s

As dazzling as the dunks are, it is Cooper’s defense that has helped make the Lakers a different team. With his speed, long arms, and fast feet, he plays super scorers—like Erving, Thompson, Gervin, Walter Davis, and Paul Westphal—bellybutton to bellybutton. Or, guarding players where there’s more chance to gamble, he darts around playing the passing lanes, double-teaming, flicking, balls away, or diving for them when they’re loose.

The upshot is that when Westhead sends in Cooper in the first quarter, the tempo almost always picks up. And, as the rest of the league has learned, up-tempo is the Lakers’ game. When they run, opponents are better off hiding.

This is especially true when Cooper is on the floor with Johnson, Nixon, Wilkes, and Abdul-Jabbar, giving the Lakers their fastest team, the so-called “small” unit. It really isn’t small, not with Cooper (6-6) at guard; another alleged guard, the 6-8 Johnson, moving up to power forward; and the 7-2 Abdul-Jabbar in the middle. When these five get together, referees earn their money just keeping up.

If you scan the statistics sheets, you might not look twice at Cooper. Playing all 82 games during the season, he averaged 24 minutes, 8.8 points, 2.8 rebounds, 2.7 assists, and one steal, while shooting 52 percent. His time in 11 playoff games has gone up to 28.2 minutes, and his numbers are similar: 8.5 points, 3.5 rebounds, 3.6 assists, 1.7 steals, and 42 percent shooting.

But basketball statistics often don’t measure a player’s impact. Cooper’s is immeasurable. In a league where some players won’t dive after anything but $100 bills, it’s rare to find a guy who’ll carry the ball to the hoop as strongly, as recklessly, as Cooper does; who’ll sacrifice his body, especially when it’s a skinny 178 pounds; who’ll play with an almost flagrant disregard for his safety; who’ll really work on defense.

“I want to win,” Cooper said, “and I don’t care what it takes. If I have to turn flips or do 360s, I’m gonna try it. I just hope I don’t break my neck.”

Because he’s only 23, questions remain before he is officially proclaimed the Coupe de Ville sixth men . . . or at least the Coupe de Ville to Bobby Jones’ Seville.

- Will he work to improve? “That’s the only danger,” Westhead said. “That Michael will see himself as a proven player. On pure talent alone, he’s probably one of the top 10 in the league.” Specifically: Even though he’s a vastly underrated outside shooter, using an old-fashioned, one-hand set shot (another paradox) rather than the conventional jumper, will he work to incorporate the drive and jumper off the dribble? With those two skills, he wouldn’t be “the next Dennis Johnson,” as some call him. He’d be the other one.

- Will he stay happy playing 25-30 minutes, when he might play 35-40 minutes someplace else and eventually make twice as much money? “I’ve never been a moneyholic,” Cooper said. “Having a little money now is a little more than I ever had before. I‘d play for free . . . room and board. Just give me a uniform. As far as my time goes, if we’re winning, I’m gonna be at content. Twenty, 25 minutes doesn’t take a lot out of you.”

Westhead: “For 25 minutes, Michael can go full-tilt. I think it helps him—and us. Besides, if you’re treated like a starter, that’s what really matters.”

It’s no secret Cooper was unhappy playing part-time months ago. But those feelings, he says now, are more a byproduct of insecurity about his status with the Lakers and the condition of the surgically repaired knee than anything else.

Now Cooper is on a high, and who says Magic Johnson has the Lakers’ only infectious smile? Cooper also has a lively, upbeat personality and some habits that set him apart. He eats like a horse—seven pieces of sourdough bread with supper, he says. He complains, half kiddingly, about not getting publicity, then is sometimes as hard to track down—for interviews—as Robert Redford.

He wears the strings of his basketball shorts outside the waistband—an old superstition. He relaxes before games by jiving with a ballboys in a small room adjoining the locker room. And then, before the Lakers take off down the corridor, he stretches and contorts that rubberized body the way no one else does.

“He’s like a panther,” Westhead said, “the way his muscles are taut and stretched, as if it’s attack time. The analogy may not be appropriate, but if you can envision what a hired gun goes through before making his hit . . .”

Like a lot of his peers, Cooper seems to cruise, though in reality this is the most-exciting time of his life. The national press is finally discovering him, and he’s discovering more about himself as he stays awake nights, thinking about guarding Dr. J, and thinking, too, about a championship ring. Cooper has played on winning teams all his life, but never a champion. Champion? Some people still think Cooper is just lucky to be a Laker.

“I’ve never been to the finals of anything and always wanted to know what it felt like,” he said. “There’s nothing like it. I’m a very emotional person and, if we win the whole thing, I don’t know how I’m gonna handle it. Imagine, the biggie. I might sit on the floor and cry.

It’ll be one of the few times the Lakers could keep him on the ground.