[Recently, I spoke with an NBA player from the 1970s about guarding Archie Clark and his crossover dribble. The player chuckled and admitted the impossibility of stopping the move. But he added, “Your only hope was to stick your hand in there and hope it hit the ball when Archie crossed over. You know who taught me that? Donnie Ohl.” He then went on to sing the praises of Ohl as a savvy veteran during his latter NBA days with Atlanta. The name, of course, rang a bell. Mainly from Ohl’s all-star years in Baltimore (1964-68). As they say, Ohl could shoot it.

I started digging around for more on Ohl, and I came upon the following two articles. Up first is from the paperback Basketball Stars of 1962. The short article, written by the-then Boston stat king and publicist Bill Mokray, offers a brief bio of Ohl during his Detroit years. Mentioned in the article is Ohl’s dry, deadpan personality that could be off-putting at first and endearing in the end. The deadpan also came equipped with a healthy sense of humor. Case in point. Before the 1966 NBA All-Star Game, the NBA announced that the game’s MVP would receive a Ford convertible, then a highly desirable ride. Ohl quipped to reporters, “This may be the first game in history without an assist.” Here’s more on Ohl.]

****

Don Ohl had a king-size assignment with the Detroit Pistons last winter. All he was asked to do was to be the backcourt successor to now-coach Dick McGuire, for years regarded as the equal of Bob Cousy as a playmaker.

It didn’t take McGuire very long to decide upon his replacement. In an early season affair with the New York Knickerbockers, the one-time University of Illinois favorite came through with flying colors. As the lead swung back and forth in the late stages, Don made a couple of mistakes, as expected of any rookie. The impatient home fans started to ride him mercilessly. However, the little fellow refused to be rattled. He twice stole the ball and made a couple of nifty baskets that allowed the Pistons to squeak out a 115-110 victory. In all, Don had 17 points. It was this trait of coming back strong after making a mistake that impressed McGuire.

“He will do,” mumbled Dick as Dick Is known to mumble after a hectic windup. “What I liked best was the way he wasn’t afraid to shoot in a tight situation,” he later added in a more relaxed mood.

Don caught McGuire’s fancy as soon as the Pistons opened preseason drills. “He showed me he knew how to move the ball, was quite accurate with his shots, and was a bearcat on defense,” says McGuire. Even before the season opened, Dick remarked that barring any unforeseen reversal of form or injuries, he would team up with Gene Shue as the starting guards.

Such confidence in Ohl was borne out by the season’s statistics. Don was the team’s third-highest score with 1,054 points for a 13.3-point average. He also showed up well as a playmaker, with 265 assists.

This newest Piston hails from a little manufacturing community in southern Illinois, about 18 miles north of St. Louis. His dad, Elmer Ohl, was quite a schoolboy athlete at Mascoutah, IL., starring in track, baseball, and basketball. His sister also quite often hits the columns of the local Intelligencer newspaper with her golf and tennis scores.

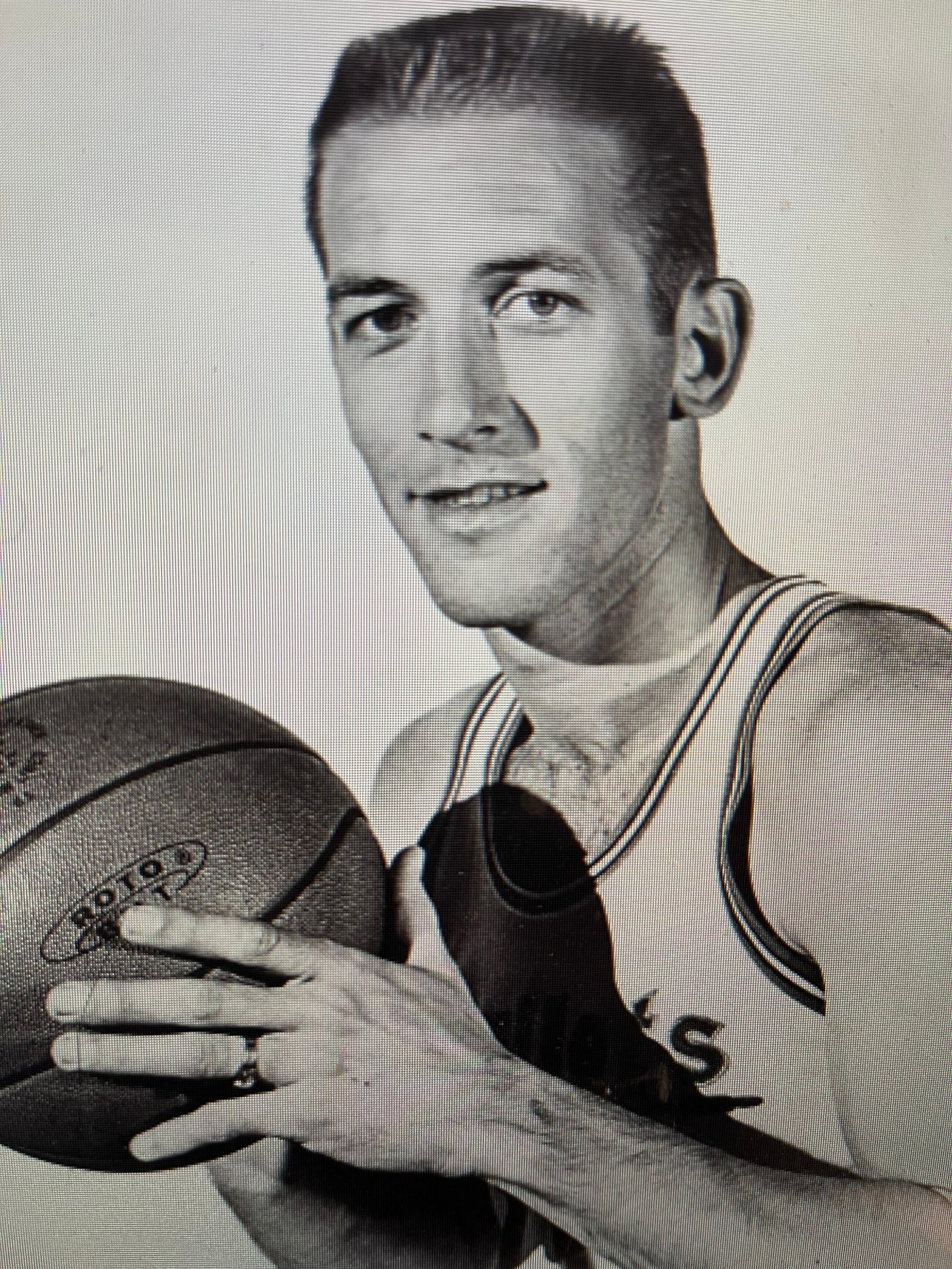

When the American Telephone Company assigned Mr. Ohl to Edwardsville in 1946, young Donnie continued his sports activities in the local school system. Although somewhat quiet and colorless, even to this day, Donnie attracted quite a reputation in golf, baseball—as a second sacker—and in basketball, when he starred in the backcourt. He proved quite a local hero with a jump shot that was fashioned after pro and college stars he had seen on television.

Coach Joe Lucco, assistant principal since 1960, who earlier had an excellent coaching record, in addition to serving part time as a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, always contended that Don might have made the big leagues in baseball if he wasn’t so wild about the roundball game.

Among Don’s greatest achievements was playing for the Illini when they snapped the University of San Francisco’s three-year, 60-game winning streak, the longest in college annals. At Champaign, Don played a steady game. He had successive scoring totals of 147, 343, and 431 points. In his senior year, he came in third in the Big Ten scoring race with 295 points. He twice made the all-conference club.

It Is well known that in 1958, the St. Louis Hawks were hopeful of landing the Edwardsville fellow so that he might develop into a hometown drawing card. But Philadelphia named him on the fifth round. “I was quite skeptical as to whether I was good enough to play pro ball,” Ohl explained last summer to Al Pritzker, the Edwardsville Intelligencer sports editor, during a visit to the hoopster’s stationery store.

“It was quite a decision to take, as I look back. Let’s look at it. I was the 37th selection in the draft. I was fifth on Philadelphia’s list (the Warriors earlier chose Guy Rodgers, Lloyd Sharrar, Frank Howard, and Temple Tucker), and I was somewhat small by NBA standards. I figured a more certain future faced me if I went with a big company, particularly since I majored at Illinois in commerce.”

In signing with the Peoria Caterpillars, the 6-feet-3 crewcut continued his improvement. He was named to the 1960 AAU All-American team as the Cats won the annual tournament in Denver. His showing so impressed Fred Zollner, the Pistons’ millionaire owner, that he purchased Don’s contract from Philadelphia owner Eddie Gottlieb.

Few games pleased the rookie more than the one at St. Louis last February when fans held a “night” for him. Several hundred Edwardsville citizens were among the 7,115 present as the Pistons put on a great rally to knot the score at 124-all, only to have Cliff Hagen pop in four in a row to account for a 135–134 victory. There was some satisfaction for Don, however, as he hit on six of his patented jump shots, and all but one of his eight charity tosses, to contribute 19 points.

Ohl singles out Lenny Wilkens as the most-troublesome opponent in his rookie season. He explains this by saying that “he has very good hands and is quick; he always got a piece of the ball whenever I dribbled.”

[Let’s fast-forward to the April 1966 issue of SPORT Magazine. Ohl has been moved to Baltimore now, and writer Doug Brown has this to say about the Bullets’ all-star.]

It frightens Don Ohl when he thinks of it now. In 1960, even before his pro career began, he decided to quit basketball. If he had done that, heaven forbid, he would have missed so many things.

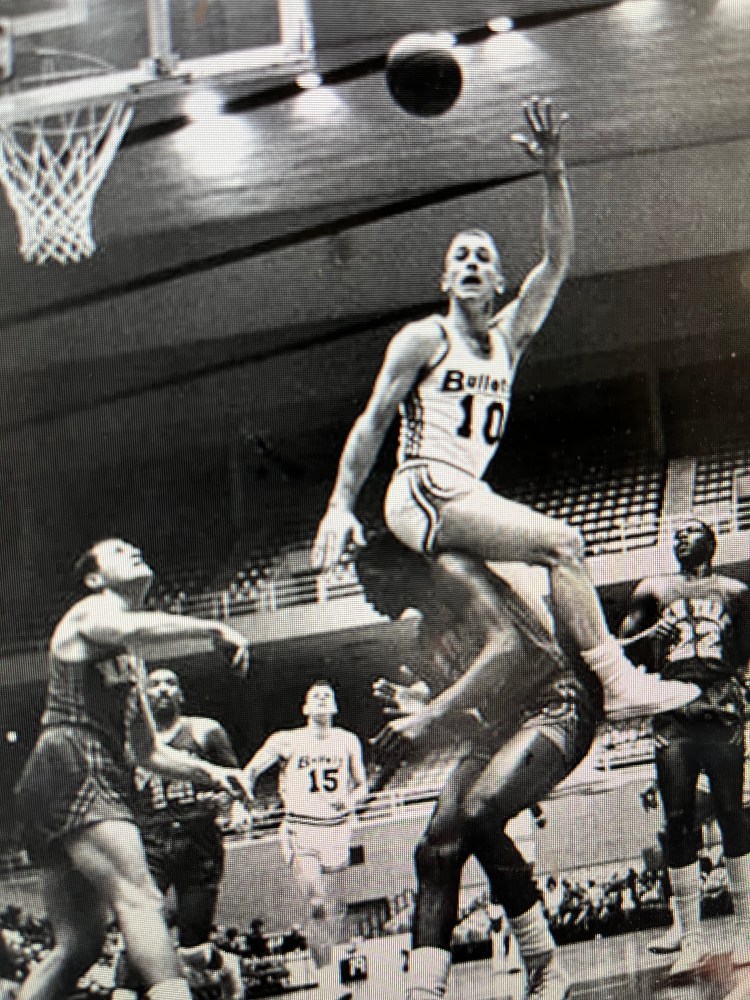

For one, he would have missed that confidence-shattering experience of playing under Charley Wolf. For another, he would have missed that confidence-building experience of playing under John (Red) Kerr. And he would have missed that $23,000 the Baltimore Bullets are paying him to throw up the sweetest jump shot in the National Basketball Association this side of Dick Barnett.

When Ohl graduated from the University of Illinois, he had no intention of playing pro basketball, even though the old Philadelphia Warriors had drafted him. “I wasn’t sure I was good enough to play in the NBA,” he says. “Besides, I wanted to go into business.” So, he set up an office-supplies firm in his hometown of Edwardsville, Illinois, and played industrial basketball for the Peoria Caterpillars, leading them to the national amateur championship in 1960.

That summer, he had decided not even to return to the Caterpillars. He was finished with basketball. Then he began getting phone calls from Nick Kerbawy, general manager of the Detroit Pistons, who had bought the rights to Ohl from the Warriors.

“Finally,” Ohl says with a wry smile, “I signed a contract just to keep him off my back. Then, in the fall, I tried out with the Pistons, and my attitude changed. I found I was good enough to play in the NBA, and I realized I could still keep my office-supplies business going. It has worked out wonderfully. I enjoy playing basketball. I’ve been able to build my business.”

A guy of 29 could hardly want more. Especially a guy at 29 who, as the 1965-66 season passed the halfway point, was leading the Bullets in scoring with an average of over 22 points per game. But check that age again. Twenty-nine.

“I should have been at my peak a year or two ago,” Ohl says. He is reluctant to drag out skeletons—in this case, Charley Wolf’s—but he knows he must if he is to explain his belated basketball prosperity. Wolf was the Pistons’ coach in 1963-64, the season before. Ohl, Bailey Howell, and Bob Ferry were traded to the Bullets. The Pistons were not overly fond of Charley.

“He restricted our play—mentally, and psychologically,” Ferry says. “It wasn’t exactly a personality clash. Charley had a lot of fine qualities. But he had the knack of handling things the wrong way. He treated us like we weren’t grown men with families.”

It was common knowledge that Wolf was strict. In training camp, 30 miles north of Detroit, the players weren’t allowed to have cars. They couldn’t leave the lodge without Wolf’s permission and, if they wanted haircuts, they had to go into nearby Marysville as a crew in a delivery truck-type van with one man appointed as leader to keep the others from straying. Once, after the Pistons won a game in Toledo, 60 miles south of Detroit, Wolf made the players return on the team bus, leaving the wives to follow in private cars.

While the Wolf-type discipline might bring out the best in some teams, it did not seem to bring out the best in the Pistons. They finished last that season after having made the playoffs the year before with the same personnel. For Don Ohl, the thing came to a head when Wolf benched him for two games for “lackadaisical play.” Naturally, it got in the newspapers.

“Finally, I began to lose my confidence. My scoring fell off, my shooting percentage fell off—everything was below par. It’s set me back a year or two, and I had just come off my best season.”

He had just come off the 1962-63 season. In it, he had average 19.3 points per game and had field-goal and free-throw shooting percentages of .439 and .724, respectively. Then, under Wolf in 1963-64, his figures slipped to 17.3, .408, and .680.

“I was getting close to having my career ruined by what he said in the papers,” Ohl says. “The other owners see that, and it hurts your stock in the league. I knew I’d have to be careful when I came to Baltimore, because everyone would be looking for a reason or excuse to believe what he said was true.

“I knew I always tried my best. I don’t feel any vengeance toward the man. He’s a gentleman. But when people ask how come I’m scoring more, I have to say I feel this is one of the reasons.”

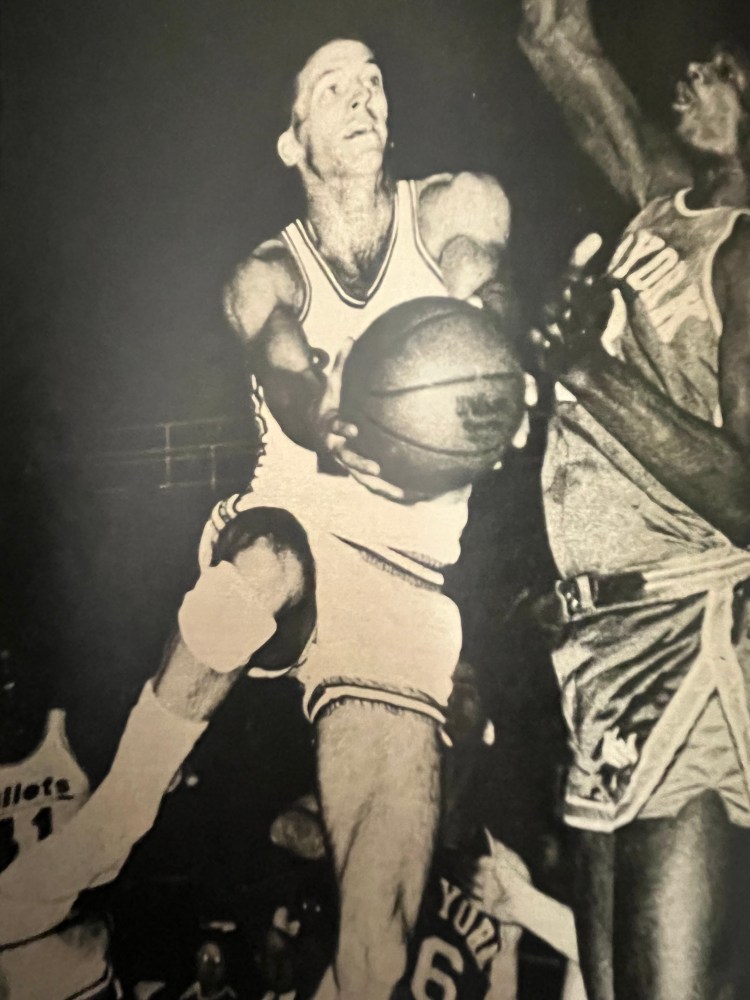

Another is the type of basketball the Bullets now play. After Walt Bellamy was traded to the New York Knicks last November, Baltimore coach, Paul Seymour installed Kerr at center. Kerr is 33 and has the old-fashioned notion that you’re supposed to pass off the ball from the pivot. “Red helps us get better shots,” Ohl says. “With Bellamy, we had to be individuals and make our own shots.”

Now, Don’s confidence has returned. Understandably cautious early in the 1964-65 season, his first in Baltimore, he finished with a rush and was named the Bullets’ most valuable player. This season, he has done nothing to make the voters believe they made a poor choice.

Although 6-feet-3, he’s among the shorter men in the NBA. Ohl is mighty thankful he’s as tall as he is. When he was a freshman at Edwardsville High, he was only 5-feet-4. He was the 11th man on the varsity and didn’t even have a uniform that matched the others.

It was then that Don Ohl’s jump shot was born. However, were it not for the fact that basketball was so big in southern Illinois, he might never have had the opportunity to polish the shot. Basketball supported Edwardsville High’s entire athletic program. The gym held about 2,500, but there were always twice that many clamoring to get in. “They used to let us out of our last period, usually a study hall, to practice,” he says.

By his junior year, Ohl had sprouted to 6-feet-1. He reached 6-feet-3 before he entered Illinois. Ohl went from Illinois to Peoria, and there he met Judy Webber, now his wife. Until they were married in 1960, Judy had never seen Don play. They were talking about this, and the life they now lead, one day recently in their apartment in Baltimore.

Judy, a pretty thing, had her hair in curlers, which meant there was a game that night. “I’ve never missed a home game except when I was having a baby,” she said. “I missed a month when I had D.J. in 1963 and two weeks in 1961 with Pam.”

When Don is on the road, Judy worries even more than most wives whose husbands have to travel. “But you’ll always be safe,” Don said, “as long as you’ve got your tear-gas gun and the butcher’s knife.”

Their visitor smiled, certain that Don was kidding. “Really,” Judy said, “I’ve got a tear-gas gun I keep on my bedside table. I got it for $3. I haven’t had to use it yet, but it’s supposed to spray 15 feet and immobilize a person. I don’t need the butcher’s knife anymore.”

The tear-gas gun is so comforting that Judy doesn’t even think about the Big Bad Wolf. And Don doesn’t think about Charley Wolf. Not anymore.