[This article isn’t quite as bold as the headline screams. But in early 1970, with a few years left on his ABA contract, Rick Barry clearly wanted out of the league. His reasons are clearly stated here, though some of his facts are garbled. For example, George Mikan wasn’t a figurehead league commissioner. Mikan also was very much a businessman. He’s also off on the ABA’s swing-and-a-miss for Lew Alcindor. It was more complicated that that. Same with his Al Davis reference.

My nitpicking aside, Barry’s missive, published in the April 1970 issue of SPORT Magazine, is worth the read more than a half century later. His earlier jump to the ABA’s Oakland Oaks was a bold move that, whether intended or not, was progressive, pro-labor, and historic. And yet, as Barry describes here, he ended up a few years later very much worse for the wear and with little to show for all the promises that the Oaks made. He wants to go home—to the NBA’s Golden State Warriors.]

****

I’ve had many happy experiences since leaving the San Francisco Warriors of the National Basketball Association and signing with the Oakland Oaks of the American Basketball Association. But this season, 1969-70, has been the most discouraging and frustrating one of my life.

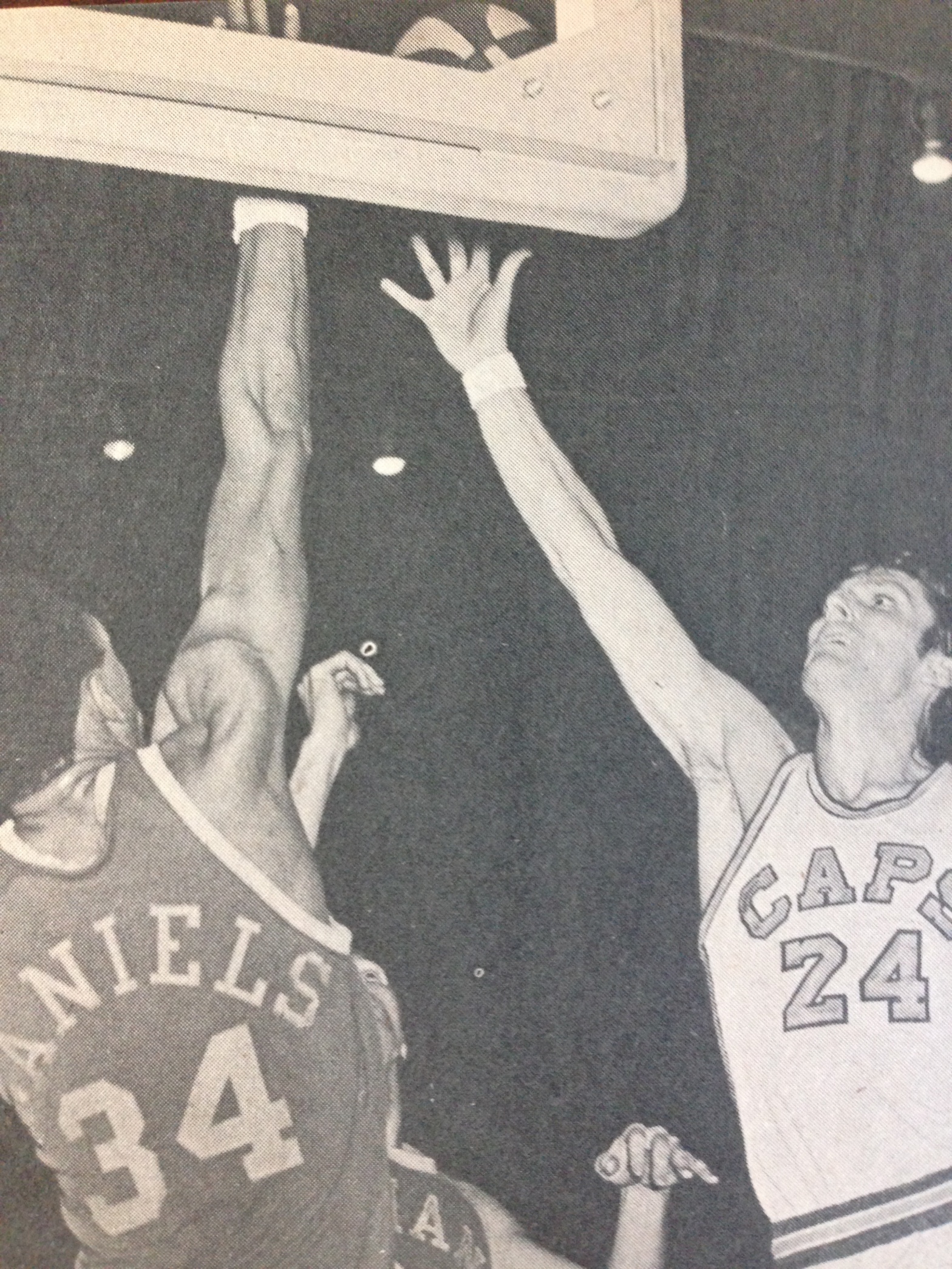

To begin with, I wish I weren’t playing in Washington. I have nothing against the people or the city of Mr. Earl Foreman, the Caps’ owner. It’s just that my home is in Orinda, in the San Francisco Bay Area, several business opportunities are there, and that’s where I want to play.

The shifting of the Oaks franchise to Washington this year came as a complete surprise to me. Had I known the Oaks ever were going to leave Oakland, I never would have left the Warriors in the first place. No way! The first time I heard about Washington was when someone called me and told me the people from Washington wanted to talk to me about playing there. I said, “What? Washington? What people from Washington?”

There had been talk earlier that the team might be sold soon, but that the new owners would keep it in Oakland. When there was a rumor that the Oaks were going to move to Los Angeles, Pat Boone, the singer and a principal stockholder, told me it wasn’t true. He told me the Oaks would never leave Oakland.

I never heard from him when the Oaks moved to Washington.

Boone and Ken Davidson, another principal stockholder, evidently were taken out of debt by the deal with Mr. Foreman and were able to save face. Meanwhile, I still have stock in Oakland Basketball, Inc. Great. I have stock in a corporation with no assets. Coach Alex Hannum and I each purchased 15 percent of the club.

Alex and I always thought the Oaks had a good future. We didn’t draw very big crowds at first, but toward the end of last season, when we were on our way to the ABA championship, we were finally getting a hardcore following.

I remember Alex saying, “We’ll have the best team in the world someday. I don’t know if it will take three years or 10 years, but we’ll get there.” He would have done it, too, because he’s the best coach in professional basketball. He’s a master strategist. He always keeps the balance of power in his favor on the court, because he is so good at matching up the players.

As for the stock, that’s all down the drain. I didn’t get anything out of it. Mr. Foreman didn’t buy the corporate shell; he bought the corporate assets. No matter how you work it out, I have nothing. When I found out, you might say I was just a little dismayed. Alex didn’t get anything either.

I went to Oakland with my family and the future in mind. Now I want to be back with the Warriors for the very same reasons. Because we want to keep our home in the Bay Area, my wife Pam stayed there this season. It’s been tough on her. And my older boy is three now, an age when he needs his father around.

By moving out of Oakland now, the ABA has lost a good area for the future. But that was just one of many problems the ABA has brought on itself. It’s biggest foul-up, definitely, was failing to get Lew Alcindor. He would have helped make the ABA truly competitive with the NBA.

Missing Alcindor finally woke up the ABA owners. They stopped messing around and buckled down. Things begin to happen. Some ABA owners talked with Al Davis, who devised the quarterback-raiding plan of the American Football League against the National Football League, and they learned something about his techniques and dealing with a rival league.

They sought advice on what they could do to fight back and effect an eventual merger on terms favorable not just to the NBA but the ABA as well. After that, the ABA owners changed from doves to hawks. They were no longer hesitant about rocking the boat of a possible merger with the NBA, and they went after big names. Denver signed Spencer Haywood out of the University of Detroit. Washington and Carolina signed NBA stars Dave Bing and Billy Cunningham for the future.

Also, George Mikan was replaced as commissioner. Mikan was a figurehead, which served the ABA’s purpose for a while. His name added something to the league when it started out, but the owners realized they needed a man with more business experience and contacts. So, he was succeeded by Jack Dolph, a former TV executive at CBS. He got quick results by arranging the television of the ABA’s All-Star Game on CBS this past January.

The ABA also signed four of the best NBA referees—Norm Drucker, Joe Gushue, Earl Strom, and John Vanak. I knew them from the NBA, and I told them I never thought I’d see the day when I would be happy to see them.

All of these moves are important ones, but you wonder if they still didn’t come too late. What the ABA needs most are the good players coming out of college. There have been three big ones to come along, since the ABA was formed—Alcindor, Elvin Hayes, and Wes Unseld—and the ABA lost all three.

They better not miss too many times or the pier is going to collapse while they’re waiting for the boat. If they want to compete, they must get the three biggest names this year—Pete Maravich, Rick Mount, and Bob Lanier, especially Maravich—or they’re going to be in big, big trouble.

But I just don’t see how the ABA—or the NBA, for that matter—is going to come up with all that money for all of them. That’s why I would be surprised if there wasn’t an agreement to have a common draft this spring. Economically, I can’t see the two leagues going on without one, and in the long run, it will benefit both leagues, just as it did in football.

The money that the rookies are getting creates bad situations. I know one player who made $25,000 to $30,000 last season and is getting $60,000 to $65,000 this season to keep his salary in line, because some rookie is making $50,000. Teams are strapped with $500,000 payrolls, and they can’t survive that way.

This may come as a surprise, but I probably could have made a higher salary if I had stayed in the NBA in the first place. I’m certain Franklin Mieuli of the Warriors would have paid me more than what I made in Oakland. I could have said, “Well, Franklin, they offered me this. What are you going to give me?” Then he could have gone back to the Oakland people and said, “He offered me this. What are you going to do about it?” But I didn’t want to hurt anybody, and I didn’t want to feel that I used them. Oakland made an offer, and I took it. I just didn’t count on the lack of finances in the. Oaks’ franchise.

It would be ridiculous for me to complain about making only $75,000 with the Caps, but if I had played with San Francisco this season, I would have made $167,500. That was the contract I signed with the Warriors after the Oaks moved to Washington. I felt that my contract with the Oaks did not require me to leave the Bay Area. But the Caps filed an injunction preventing me from playing with any other team until the courts decide which contract is binding.

Last August, when all this was beginning to take place, was a very emotional time for me. First, the Oaks’ move shocked me. Then I was back with the Warriors, playing for the first time since I injured my left knee in March of last season. I had had the medial cartilage removed in an operation, and many people were wondering if I could play as well as before. So was I.

The practice with the Warriors proved I could. I started going to the basket, stopping, cutting, moving well in the crowd. I was shooting the jump shot effortlessly. The people who were watching me said I wasn’t favoring my left leg.

Then they slapped the injunction on me, stopping me from working out with the Warriors. I was in good shape by then, but I got out of shape because of the layoff the next two or three weeks. Less than a week after I reported to the Caps, I hurt my knee again. During a scrimmage, I drove and came down wrong on my left leg. Now the lateral cartilage was messed up. I tried to play anyway, but the knee gave out a couple of weeks later in the game in Charlotte. I’m not sure the layoff after the injunction caused it, but it definitely didn’t help.

So there I was in Washington, where I didn’t want to be in the first place, and having a second operation on my knee. This one leaving me with no cartilage at all.

After the operation, I made all kinds of appearances for the Caps, did the color on TV, and I tried in every way possible to help. I also used the time trying to get mentally adjusted to the idea of playing with no cartilage in my knee. I think I have. While I don’t know of any other pro basketball player who has played without cartilage, I’d rather look at it another way: I don’t know of anyone who hasn’t played because of it.

When I made my second comeback in January, the knee would swell after games, but it would go down again. The biggest problem was getting my body in shape after the layoff. I would get tired easily. There wasn’t any pain in the knee, just little noises. I don’t know what it is except I know it’s not my cartilage making noise. In a way, I’d like pain, if it meant I could go out and still play the next game. It’s been frustrating for me to sit around so much because of injuries when I had never been hurt in my life. Before I was hurt the first time, I felt I was playing better than I ever had. That includes the 1966-67 season, when I won the NBA scoring title.

After sitting out the next season because of an option clause in my Warrior contract, I led the ABA in scoring average despite being hurt part of the season. But I’ve been doing more than scoring in the ABA. I feel like I have more responsibilities, and I play a different kind of ballgame. With the Warriors, my main asset was scoring. I could cheat a little on defense, and others would make up for it. Now, I try to play more defense. I pass and try to set up plays. I also try to do more rebounding. I didn’t have to worry about that with the Warriors with Nate Thurmond around. Ira Harge does a great job for us, but he’s not the shot-blocker or intimidator that Nate was.

But while the game itself has been satisfying in the ABA, playing in front of small crowds hasn’t been. Indiana is an exception. Those people are basketball crazy. They sell out. And they draw 6,000 or 7,000 in Denver. But it’s not much fun playing in Washington before 1,200, and it totally destroys any homecourt advantage. Washington is a good basketball area and the arena is not that bad, but the people just won’t come to that neighborhood. It’s a very difficult situation.

I may be with the Caps for another two years. I have one more year on my contract plus an option year. But I’ll be back with the Warriors by the 1972-73 season at the latest. If there’s one thing I regret about this whole mess, it’s all the trouble I’ve caused so many people—especially Franklin Mieuli. I couldn’t blame him if he disliked me. I’ve given him every reason to, but I think he understands.

I really believe Franklin has a sincere interest in his players. And I think the players feel the same way about him. To say I’m sorry for all the trouble I’ve caused him isn’t going to repair all the damage that was done. And that’s one reason why it would be nice to play for him again.

One day, I hope all this will be settled in court. Maybe the merger will help. Maybe then Franklin can do something to get me back where I belong. Meanwhile, all I can do is hope—one, that my knee holds up and, two, that I can go back home.

Wah, wah, wah. What a freakin crybaby.

Not very smart about that Oaks contract either.

The Oaks move…wah, wah, wah….”i wanna go home…not fair.”

All this from one of the 15 best players and court smart players ever in basketball.

He also made a wise ass comment about the state of Virginia when Washington moved after one year. ”I don’t want my kids growing up saying y’all.”

So Virginia sells him to New York Nets.

His article was spot on about the business of the ABA, but jeez such a public crybaby.

And the overblown danger to his career from his 2 knee surgeries…no ligament damage was involved…a meniscus and a lateral cartilage, neither is fatal to a basketball player. But Rick has to make it look to the layperson of that era like he was climbing Everest.

The innovative ABA’s main problem was the owners were not rich enough to withstand the growing pains the AFL owners did. Period.

LikeLike