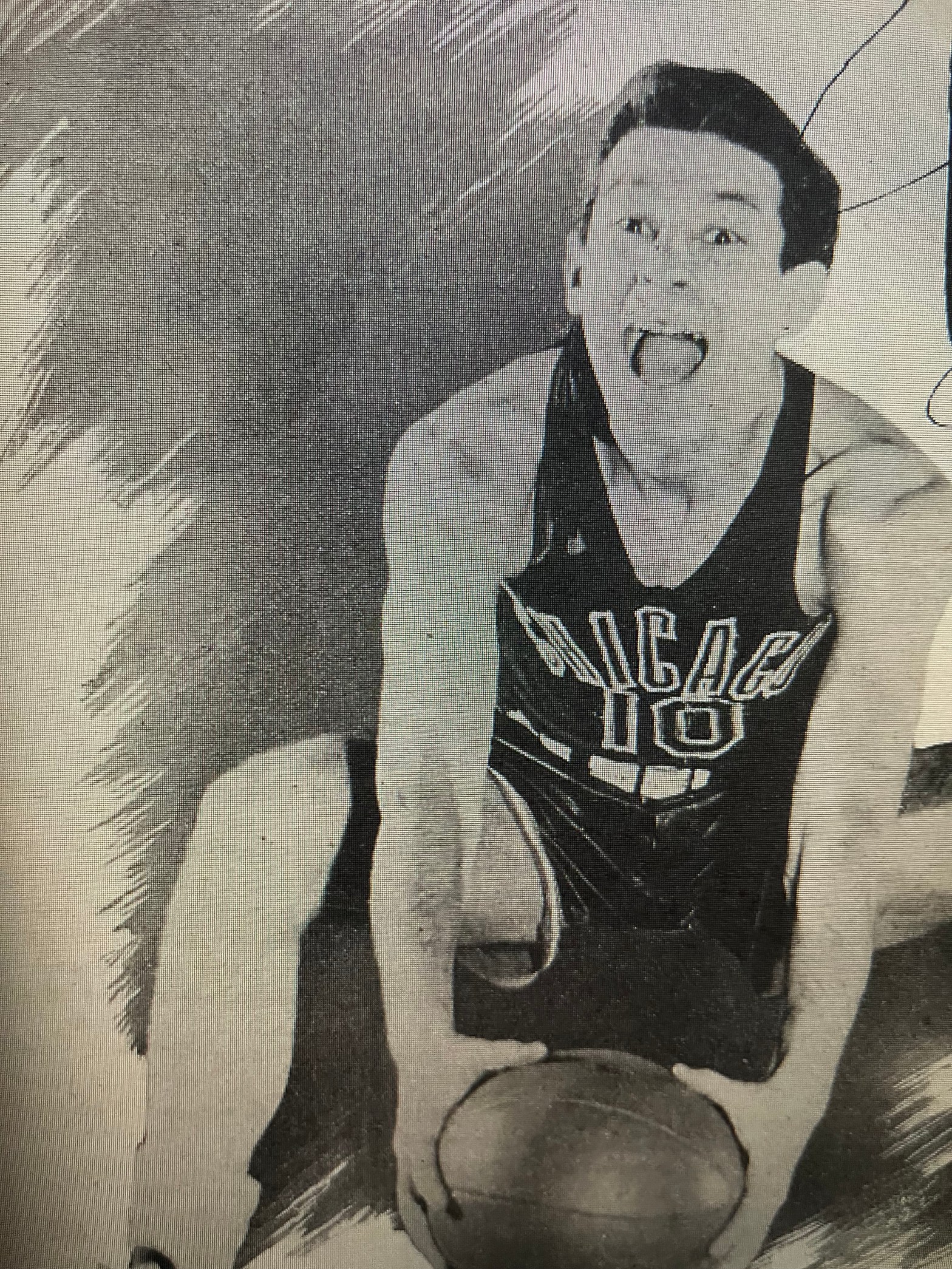

[Whether answering to “The Whirling Dervish” or “The Touch” for his array of shots, Max Zaslofsky was one of modern pro basketball’s early oh-wows who, arguably, reigned as the game’s best player, circa 1949. This newspaper clip from back then captures well the wow and the arguably:

“Joe Lapchick, the gaunt, hollow-cheeked coach of the New York Knickerbockers, looked up from a plate of Mother Leone’s shrimp that were buried beneath a succulent pink Creole sauce and said to his next-door neighbor, Alvin (Doggie) Julian of Bostontown: “These Rochester people are not going to like my saying this . . . but pound for pound, inch for inch, Max Zaslofsky is the best basketball player in the business.

Mr. Julian bolted to his feet, begging to disagree. “He’s your man,” shouted the retired college cage professor who now tutors the postgraduate Boston Celtics. “That [Bob] Davies is my man. He can do everything, and do it especially well under pressure.” Doggie had something there. And naturally, he was referring to the Kangaroo Kid’s glittering 20-point second-half performance against the Knicks only a few hours previously.” (Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 18, 1949)

Whether you preferred Davies, the Kangaroo Kid (also the Golden Tornado) . . . or the angular Bones McKinney, the giant George Mikan, the aging Pop Gates, Jumpin’ Joe Fulks, or Jim Pollard (the other Kangaroo Kid), there was no omitting The Touch from any conversation of the game’s greats.

Time has struggled to remember and not badly garble Zaslofsky’s difficult last name. But there are still some good print articles to be found to feel The Touch . . . or, if you prefer, The Whirling Dervish. Like this one from the April 1950 issue of the magazine Sports Stars. Telling it like it was is Chicago-based reporter Tom Seidell.]

****

Max Zaslofsky is the Sid Luckman of basketball. By a curious quirk, Max, like Sid, was forced to leave his native Brooklyn heaths to establish himself in Chicago as an outstanding athlete. A Luckman competing in his prime for New York would have meant a fortune to local promoters. The same situation applies in the case of the remarkable Zaslofsky, a 24-year-old whirling dervish on the basketball court.

Zaslofsky, a crack Chicago forward, is so lethal at the game that one night a few seasons ago, a rival whispered to him before tip-off. “Please go easy tonight, will ya? I got a wife and family to support.” Unfortunately for the pleader, Zaslofsky was on that night. The foe was benched in short order.

Zaslofsky, the Brooklyn kid that nobody ever really heard of until he skyrocketed in Chicago, moved so high in the basketball firmament that he achieved all-league honors in 1946, 1947, 1948. In the 1947-48 season, he established the then-record total of 1,007 points for the campaign. Every time that Joe Lapchick, his old coach at St. John’s College in Brooklyn and currently with the New York Knickerbockers, looked at Zaslofsky or read of his performances, he developed a new ulcer.

“And to think that anybody might have had him,” Joe remarks unhappily.

When the Basketball Association of America (BAA) was formed in 1946, everybody scrambled for players. Nobody knew who was who or what was what, and the big-name boys were selected right off. Zaslofsky’s name, starting with the last letter in the alphabet, was way down in the list as far as the experts were concerned. He had played for Thomas Jefferson High School in the Brownsville area of Brooklyn, and he had had one year at St. John’s (freshmen were allowed to play varsity ball just after the war), but nothing too startling resulted.

Zaslofsky’s case is slightly different from Luckman’s at this stage, because many authorities were already claiming that by the time Sid was in his final year at Columbia, he was of All-American caliber. Had Zaslosky stayed on in school, he might have been recognized as the Luckman of basketball within a few years. But a love affair, which resulted in his marriage, set his whole future career in a different pattern.

“I knew Elaine ever since we were kids—I was 13, and she was 12 when we first met—and when I was 20, I decided to get married,” says Zaslofsky.

The 6-feet-2, 175-pound Brooklyn digger had a tough choice to make. After all, he was not a big boy as far as major leaguers go in basketball. Could he make it? Two factors influenced him in making his choice—the $6,500 salary that the job offered in that season and then the encouragement afforded him by Sammy Schoenfeld, the old coach at Jefferson.

“You can do it,” declared Schoenfeld, “but you’ll have to develop more shots if you want to stick. You’ve got a wonderful two-handed set shot, but you’ll need more in the BAA.”

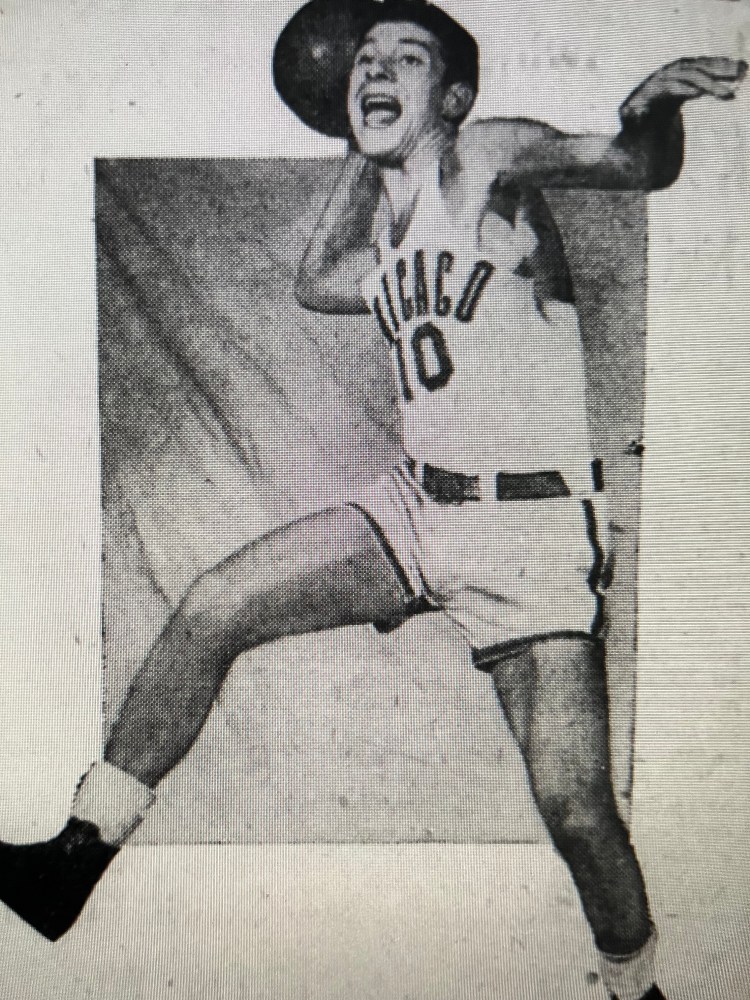

So, the summer before Zaslofsky took the plunge, he not only played in the Catskill borscht circuit, where so many varsity men and professionals compete for hotel teams, but he went back to the yard at Public School 184 at Stone and Riverdale avenues in Brooklyn. Zaslofsky practiced two and three hours a day on varying types of shots, the one-hander and the jump shot as well as the set shot. By the time that he joined up with the Chicago Stags, under head coach Harold Olsen, he was in prime condition and as versatile a shot as ever graced a Midwestern floor.

The habit that Zaslofksy engendered when he first prepared for his professional debut is one that has not left him and which accounts for the fact that he is able to stay with the murderous pace that the present 68-game schedule entails. Max practices for two or three hours a day on his shooting, regardless of weather or extraneous obstacles. It is his grim devotion to practice, which has enabled him to blossom from an ugly duckling of basketball to one of its foremost practitioners.

All of Max Zaslofsky’s life he has been in the background and, even today, he does not receive the recognition he deserves. Max went to a high school, Thomas Jefferson, which has been the incubator of great basketball players for a generation. Allie Shuckman and Max Posnack of the old St. John’s Wonder Five; Java Gotkin, Rip Kaplinsky, Dutch Garfinkle, Sam Winograd, and Sid Tanenbaum, the All-American from New York University (later the Knickerbockers and Baltimore), are some of the players bred at Thomas Jefferson. Zaslofsky, unheralded, may yet turn out to be the finest player of them all.

He was a total stranger to coach Harold Olsen of the Stags when he first reported to that sage tutor. Olsen was scrutinizing a bevy of his men in a practice session one afternoon when his eye was caught by a quiet, lean kid throwing set shots from just outside the keyhole. Olsen did a double and a triple take as Zaslofsky hit 25 consecutive baskets. “That boy will do a lot of playing for me,” Olsen remarked.

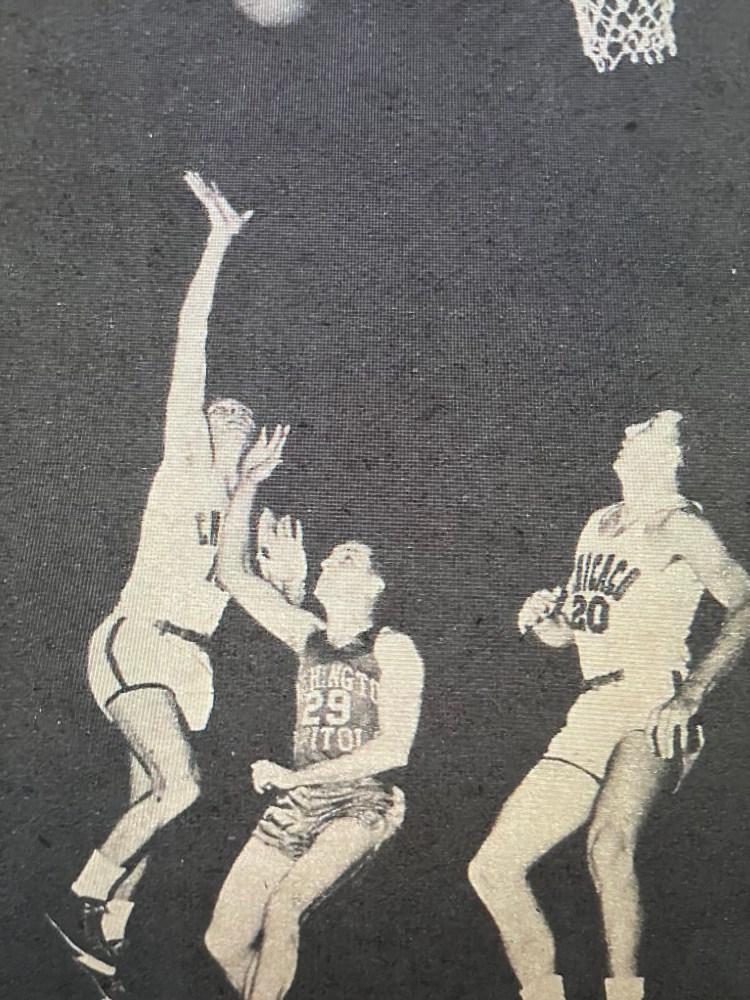

And Zaslofsky did. In his first season, he proved to be the fifth highest scorer in the league, averaging 14 points a game. Jim Seminoff, formerly of the University of Southern California and later traded to Boston, used to run interference for Zaslofsky, something like [football’s] Forrest Evashevski did for Tommy Harmon. Then Jim would yell. “Pop Max.” And the Brooklyn sharpshooter would pop.

In the 1947-48 campaign, with the Whiz Kids in swift action next to him, Zaslofsky averaged 22 points a game to lead the league. In anybody’s book, this accomplishment is phenomenal. Joe Fulks of the Philadelphia Warriors is 6-feet-5 and has tremendous spring; the inimitable George Mikan of Minneapolis is 6-feet-10. Within his physical span of 6-feet-2, Zaslofsky is perhaps the foremost player in basketball.

“Some critics have accused Zaslofsky of basket-hanging,” said Mikan this summer, “and others have commented upon his habit of picking up loose balls. He picks those loose balls because he has a sixth sense for following the ball.”

Then Zaslofsky has a cat-like grace to go around a man, and it is a grace which is not predicated upon speed. His eye is as unerring as any in basketball, and he is shiftiness itself on the prowl. Furthermore, he has an art for legitimately bumping a rival so that he is picked off on a pivot. Zaslofsky has the daring to maneuver into a pivot himself if he thinks that he has even an inch of height over the other fellow.

With all these qualifications and potentialities, Zaslofsky has never truly come into his own. Although he was in all-scholastic skill while at Jefferson, the elongated Harry Boykoff and Hy Gotkin received the plaudits at the beginning of his scholastic career. Then the redoubtable Sid Tanenbaum, considered one of the finest ballplayers in years, relegated him to the shadows.

By a coincidence, it was while he was at the Wingdale Country Club, managed by Sid Luckman himself, that Zaslofsky is said to have been talked into trying out for the Chicago Stags. A guest at the hotel, interested in the Stags, is alleged to have persuaded Zaslofsky to try out for the team. Zaslofsky, newly married, has been toying with the idea of switching to Long Island University or of seeking a berth in the new pro league. He took his chances in the pro game without the benefit of any fanfare.

Another version of Zaslofsky’s removal to Chicago is that Ned Irish and Joe Lapchick, coach of the Knickerbockers, bundled off a number of rookies to the Stags, including the kid from Brownsville and Tanenbaum.

Life’s little oddities are such that the All-American Tanenbaum, who was publicized from one end of the coast to the other, is now a respectably married, businessman out of basketball, while Zaslofsky, the kid who wasn’t considered good enough to require persuasion to stick on at college, is on his way to becoming a basketball immortal.

“I hope to play basketball till these go,” he says, pointing to his legs, “and I hope that that won’t be until I’m about 30. Meanwhile, I’m looking about for a business when I’m through. Maybe a boys’ camp or a sporting goods store.”

It’s the feeling in this corner that basketball’s ugly duckling will be flying about Chicago’s environs for a long time. As in the case of Sid Luckman, they’d be crazy to let Brooklyn’s Max Zaslofsky go.

[The Stags, in financial trouble, folded at the end of the 1950 season. Zaslofsky landed with Lapchick’s Knickerbockers, where he spent three seasons before rolling on to Fort Wayne, Baltimore, and Milwaukee. Zaslofsky retired after the 1955-56 season and would help to found the American Basketball Association a decade later. Although Zaslofsky made the cut for the NBA’s 25th Anniversary Team in 1971, he’s hasn’t been enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.]