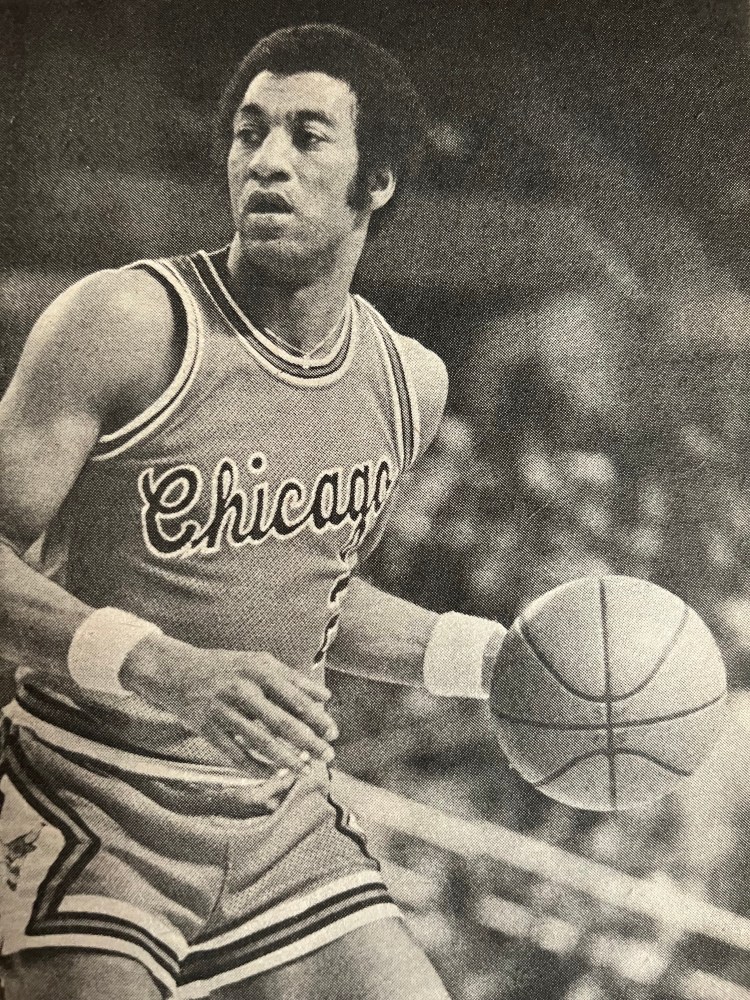

[Norm Van Lier spent 10 action-packed seasons in the NBA (1969-1979), seven of them collecting floor burns for the Chicago Bulls. Because of Van Lier’s confident, hard-charging demeanor, he was booed and cheered lustily at home and away, somewhat akin today to Patrick Beverley on the loose in an NBA arena.

In this article, published in the May 1978 issue of Basketball Digest, Tom Fitzpatrick of the Chicago Sun-Times visits with the 30-year-old Van Lier during what would be his final season as a Chicago Bull. By October 1978, new Bulls’ coach Larry Costello surprisingly waived Van Lier, and the latter was picked up, ironically, by Costello’s former Milwaukee Bucks. Doubly ironic, Van Lier and Milwaukee fans never got along well. But they mended fences for Van Lier’s final NBA season in 1978-79. BTW – I’ve got another late-career Stormin’ Norman story up my sleeve, and it will be up soon on the blog. Until then, Fitzpatrick’s short story is definitely worth a look.]

****

To Norm Van Lier, it seems only yesterday he was playing his first full season for the Chicago Bulls and Dick Motta, that stern taskmaster of a coach, with whom Van Lier still has a love-hate relationship. But it isn’t yesterday. Six full seasons have already slipped by since that day in November 1971 that Van Lier confronted the domineering Motta to demand he be a starting guard.

Van Lier had been traded to the Bulls by Cincinnati only six games previously. Motta had been using him sparingly. Van Lier smoldered. Then he did something that is characteristic of him: He elected to provoke a confrontation with Motta.

Van Lier accosted Motta and began speaking frankly. “Hey, man,” Van Lier said, his chin jutting out the way it does when he goes after an erring referee, “I didn’t come over here to sit on the bench. I came here to be a starter. I played at Cincinnati two years, and there are only two guys in this league who can make assists. I’m one of them, and the other guy is Tiny Archibald.”

Motta’s verbal reaction has not been recorded. But the record books show that Van Lier became one of the Bulls’ starting guards shortly afterwards, and he has held the post ever since.

During all those years, Van Lier has been the one player that Chicago Stadium fans have identified with because, on the court, he seems no taller than anybody else you meet on the street. Indeed, Van Lier brings out the Walter Mitty in every fan in the stands, white or black. He steals the ball. He makes the clutch shots. He gets angry and shouts at the refs. He picks up chairs. He dives on the floor. He never backs down from a physical challenge.

Van Lier was relaxing on a living room couch in his 13th floor condominium on Chicago’s Gold Coast the other day, looking out over a frozen shore of Lake Michigan, just below. Behind him, a large black-and-white photograph hangs on the wall. It has been blown up on heavy cardboard. It shows the starting Bulls five in the Chicago Stadium’s glaring spotlight just before a game is to begin.

Van Lier glanced at the photograph. Only he and the other for men in the picture can really know what feelings go through your mind at a time like that. “I always tell myself before I go on the court that I’ve got to do my best tonight, while I still can. If I do that, then I’ll be satisfied.

“I don’t worry about the boos. I’m in the twilight of my career. I always said you get the cheers when you go up the ladder, and you’re gonna get the boos when you come down.”

Van Lier talks about being in the twilight years, but he really doesn’t believe that. He still talks about playing another four years under his present contract agreement with the Bulls. It is that crucial four years that will make it financially possible for him to stop playing and work seriously toward being an NBA coach, something he seriously wants to become.

“I could coach right now,” Van Lier, says suddenly, “given the power. I know basketball. I could handle it right now.”

Van Lier maintains fierce loyalties. One of those fixations is with what he calls, “the Old Bulls.” He talks about Jerry Sloan, Chet Walker, Bob Love, Tom Boerwinkle, Clifford Ray, and Bobby Weiss.

“Sloan and Motta,” he says now, and it is almost as though Van Lier is sitting there looking out the window and talking to himself. “These were real people who worked. I learned what it meant to work playing with these guys. They didn’t have the ability this team has, but they worked so hard. They sacrificed so much for each other.”

Van Lier shifted forward on the couch. He clasped his hands in front of him. “I admired Jerry from the start. My style of play was always like his. We’d both dive for the loose balls. We’d both do anything to get the ball and get two points.”

When Van Lier joined the Bulls for the second time (he had been shipped to Cincinnati as a rookie and remained there for two seasons), Sloan was the acknowledged leader of the team. “Jerry made me part of what was happening right away. He was a real human being. It was strange. He was a white person, but he was for everybody.”

Every setback that Van Lier is handed in life becomes magnified because it usually takes place in a spotlight. He has no privacy. Everything that is done to him or by him becomes public property.

When Van Lier got divorced, it was in all the papers. When he had an altercation with referee Darrell Garretson two years ago, it became a cause celebre for months. His divorce was much discussed, and so was his invasion of a Pennsylvania police station several years ago.

But Sloan has always been there to help. “I love Jerry Sloan and his wife,” Van Lier said now. “I remember when I played against him when I was with Cincinnati. We got into fights, but we always ended it with a handshake.

“Jerry’s wife always gives me advice when I’m down. They’re such good people. I can’t tell you what it means to me to have Jerry Sloan on the sidelines to shake hands with before I go onto the floor. I like to feel that when I go out on that floor, I’m taking a little bit of Jerry with me. That I’m bringing a little bit of the Old Bulls onto the floor. I mean that.”

One recent night, before Van Lier took the floor to play against the Indiana Pacers, Sloan took him aside to give some advice. “He told me to be cool and to take the punishment. He told me not to worry about the boos.

“I said to him, ‘Jerry, you don’t know what it’s like to get booed by your favorite people. You can never know because you are their real favorite, regardless of what Van Lier ever does.’”

Van Lier was referring to the now much-talked about hatchet job that was performed on him by Pacer guards, John Williamson and Ricky Sobers. “I’m a little older now,” Van Lier said. “I know where they’re coming from. I took a beating, but we got the win. I have nothing against Ricky and The Man (Williamson), but it’s just that I’m beat to hell.”

Van Lier stood up and walked toward the window and gazed at the lake for a moment. “I’m not a dirty ballplayer,” Van Lier said finally. “I’ll be the first to pick you up off the floor. But I’ll retaliate when somebody knocks the hell out of me.”

Van Lier’s macho reputation frequently causes the people whom he encounters in restaurants and bars to challenge him. “One night I was on television with [sportscaster] Johnny Morris, and I was trying to help out the guy who owns Faces, a local bar, by telling Johnny that I was going to go there that night.

“So I am in Faces, and a wise guy comes up behind me and starts a fight with me. He wants to be a big man. The guy who owns the joint blames me. So, I won’t go to Faces anymore. I’ll stay out of those places from now on.”

Van Lier moved to his two-bedroom apartment at Richey Court partly for tax reasons and partly to get away from the Newberry Plaza high-rise and Rush Street ambience, where it was impossible for him to even go to a grocery store without being hassled.

Van Lier himself is now a stylish dresser who drives a Jaguar in the summer and a Volvo in the winter. He has come a long way from Midland, Pennsylvania, a town with a population of 10,000 in the western part of the state.

He was a three-sport star at Midland High, playing quarterback and safety on the football team, guard on the state championship basketball team, and shortstop on the baseball team. “In Midland, you either worked in the steel mills or you went out of town to do things,” Van Lier said. “If you were Black, the only way you could do it was through sports.

“Basketball wasn’t my first love. Baseball was. I was offered a $25,000 bonus right out of high school to go with the St. Louis Cardinals. But they wanted me to go to Little Rock, and Richie Allen, a good friend of mine, had had a bad experience there because he was the first Black player. I decided to go to college.”

Van Lier grinned again. “You know, I went to see that movie, One on One. It reminded me of what happened to me when I reported to the University of Cincinnati as a freshman. They told me I had a scholarship, but before we were even enrolled, the coach lined up all the guard candidates and had us go against each other, one on one.

“I knew what he was doing. If I couldn’t make it, I’d never even get into school. I turned right around and went back home and enrolled at Saint Francis College.”

After graduating as a history major, he could have gone in any of several directions. Van Lier could have tried pro baseball. There was even an offer of a tryout from the Cincinnati Bengals as a defensive back. Van Lier stuck with basketball, however, and ended up playing his first two years under the legendary Bob Cousy.

“My first roommate was Adrian Smith,” Van Lier recalled now. “I was a rookie, right. So, I’m sitting in the hotel room after our second road game. It was the Boston Celtics. I’m watching television . . . [Adrian] walks into the room. He doesn’t say anything. He turns off the television. He turns out the lights and gets into bed. I’m sitting there in the dark. I said to myself, ‘What the hell is going on?’

“I go to bed. I’m fast asleep. Suddenly, it’s six o’clock in the morning. Adrian Smith is up again. He’s bouncing around, getting ready to go to church.

“I got a new roommate. It was Oscar Robertson. I couldn’t believe it,” Van Lier shakes his head. “Every night, Oscar sits around the room and makes out his plans for the following game. He sits there smoking a big cigar and sipping on a glass of wine. ‘I think I’ll score 38 points tomorrow,’ he says.

“The next night, Oscar scores 38 or 36 or maybe 40 points. Then he sits in the room and says, ‘Tomorrow night you can have the ball. I’ll just score 18 or 20.’”

Van Lier grins. “You couldn’t believe it. The next night, Oscar would score 18 or 20 and, sure enough, I’d have the ball.

“He’d come back the next night and say, ‘I’m the best, Norman, I’m the best. They talk about Jerry West and everybody else, but don’t ever forget: I’m the best. It’s what you have to believe all your life, Norman. You always have to believe you are the best.’”

Suddenly, you realize where so much of Norman Van Lier comes from. It has its roots in the fierce competitors, like Cousy and Oscar and Sloan and even Motta. It has helped to mold Norman Van Lier into what he is and will keep him that way always.

“You have to know how to take the lumps,” Van Lier said now. “You have to be ready to be a hero one day and then hear the boos the next. But I always want them to remember that I wore number two for a reason. I want them to remember always that I tried harder.”