[Open a copy of Bernard King’s 2017 autobiography Game Face, and the dust jacket informs you that King is a Hall of Famer, “one of the most dynamic scorers in basketball history,” a very private person, and somebody who overcame myriad personal and physical challenges. All true.

What about his younger brother Albert? No mention in the dust jacket, and Albert factors into just one of the book’s roughly 300 pages. However, had Game Face come out in the 1980s to celebrate Bernard in his high-scoring prime, Albert likely would have factored more prominently into the text. He might have even merited a mention in the dust jacket.

That’s because in 1977, Albert arrived on the basketball scene as the nation’s premier high school prospect. A can’t-miss college star who, if he’d wanted to risk it, could have jumped straight from the preps to the pros. Here’s a sampling of young Albert’s accolades from back then:

Ken Kern, Albert’’s coach at Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton High: “Albert King has to be as graceful a basketball player as you could ever expect to see. Absolutely nothing he does is forced. Actually, I think his style is very similar to Julius Erving’s. He’s a gazelle with a tremendous amount of court sense and just the right amount of unselfishness.”

Pat Williams, Philadelphia 76ers: “I saw him play as a 15-year-old sophomore, and he was amazing for a kid that age. I felt that way not just because of his natural ability but also because of his complete awareness.”

Lefty Driesell, University of Maryland: “The thing that impresses me most about Albert King is that he’s got great feel for the game.”

Albert certainly had his big moments in college playing for Driesell, but he never lived up to his advance star billing as a pro. “Streaky,” “finesse,” “lackadaisical” was some of the adjectival shade cast to checker his eight-season NBA career. It also likely explains why, by 2017, Game Face co-author Jerome Preisler mostly took a pass on the Bernard-Albert storyline. But in 1984, it was a thing, and writer Richard O’Connor explores their similarities and mostly differences on the court in the following article. Warning, the article doesn’t take a deep dive, just contrasts the two. But it’s a good overview just the same. The article ran in the May/June 1984 issue of the short-lived New York Sports Magazine.]

****

Bernard and Albert King are the second and fourth sons among Thomas and Thelma King’s six children. The King boys grew up in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn (where their parents still live), an indigent enclave a few blocks from the Navy yard, which throbbed with violence and had more than its share of broken people living in broken houses on broken dreams.

But the King home was a loving, disciplined one. The boys had to be in early every night, and loud music was verboten. “Our mother was strict, but totally dedicated to us,” remembers Albert.

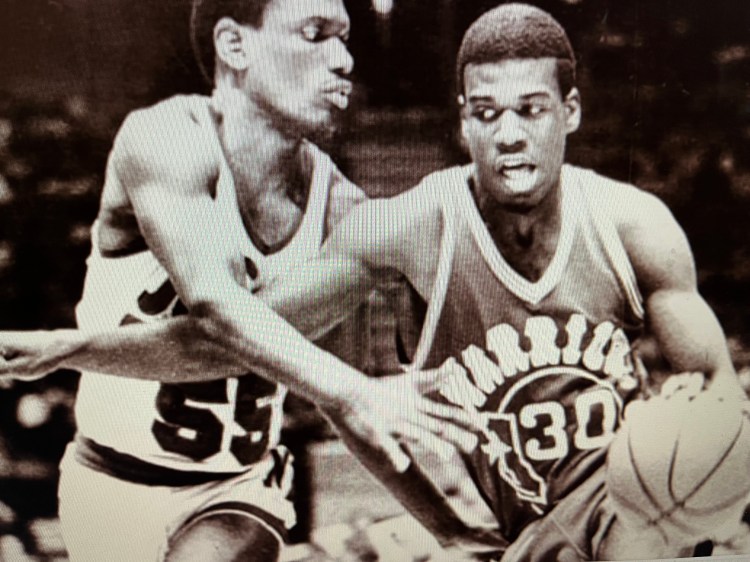

Basketball was the hard drug of the neighborhood, and like most city kids, the brothers took to the game as if by instinct. Three years apart, they starred for Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton High. They both mastered the sport, dominated it, became national figures because of it. They were even both first-round draft choices of the same pro basketball team—the New Jersey Nets. After that, the similarities end.

Albert achieved such an extraordinary level of success as a youngster, that, as a result, nearly everything since has failed to measure up. In a way, he has become the victim, as well as the beneficiary, of his own publicity. Bernard came into prominence later in his career—during college—and though his fame very nearly destroyed him as a man, it forced him as a basketball player to grab the game by the lapels and shake all the greatness that he could out of it. That simple difference has shaped the course of the professional careers of the King brothers.

****

Until his senior year at Fort Hamilton in 1973, Bernard was only a fair high school player who received “very little pub.” As a matter of fact, Bernard himself doubted his own ability. He grew up believing he had to work harder than the next guy if he wanted to win.

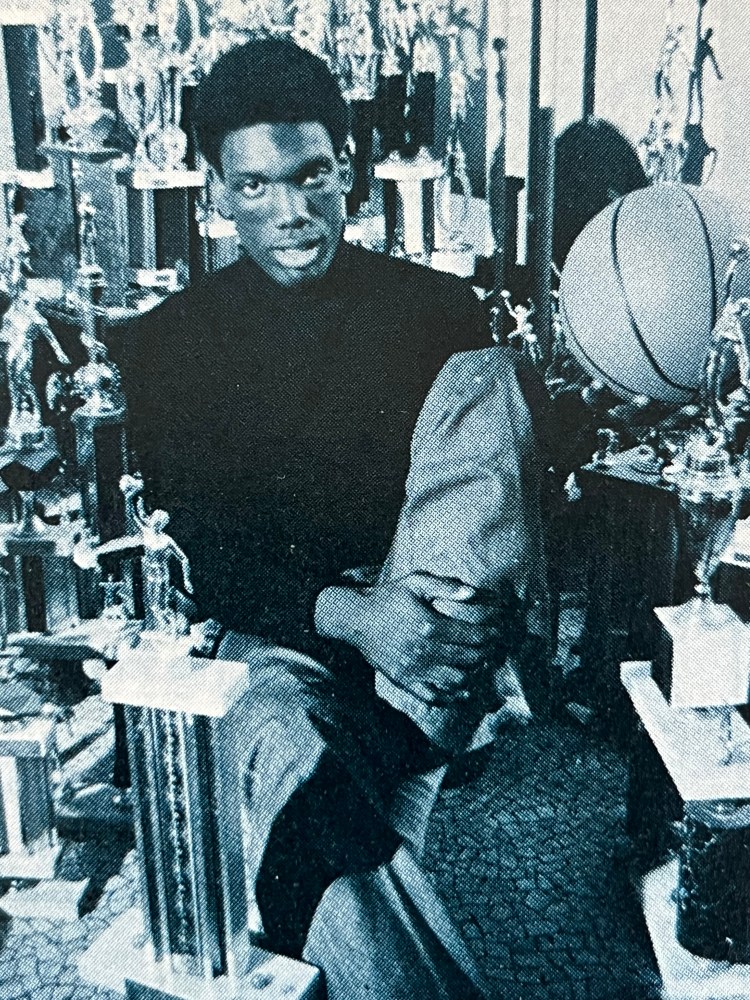

Albert King, on the other hand, was America’s darling by the time he was a freshman. Many still feel he was the most-publicized and possibly the best scholastic player from the metropolitan area since Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was Lew Alcindor at Power Memorial in 1965. In his senior year, Albert was All-Planet, averaging a phenomenal 39 points and 22 rebounds a game.

By then, he had already been featured on national television, and was being recruited by everybody, including the NBA. “Everybody is Courting the King” blared a Sports Illustrated feature story. When he arrived at the University of Maryland, in 1977, people were already playing trumpets and throwing rose petals in his path. Albert took the whole thing in stride. Nothing to get hung about. Strawberry Fields Forever.

In Bernard’s senior year of high school, he had visited the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, getting off the plane to blaring sirens and flashing lights. A convertible limousine took him to a midtown parade, which culminated in the city’s fathers presenting him with a fancy scroll proclaiming it: “Bernard King Day.” The attention and adoration nearly blew Bernard’s cookies. A few weeks later, he signed a letter-of-intent with Tennessee.

“Up until that visit, Bernard had never received much fanfare,” remembers one family friend. “I think after that, he felt an obligation to go to UT and be as great as he was heralded to be. But in doing that, he put a tremendous burden on himself. It’s obvious after all that happened, that he wasn’t mature enough to handle it.”

In his first game for UT, Bernard scored 42 points, and the fans went nuts. Soon, Bernard King was damn near sainted in Knoxville. But it was only on the court where he found self-expression and contentment. Off it, he was shy and awkward. Instead of luxuriating in his fame, he withdrew to write poetry. And drink.

Bernard knew he was a celebrity. The problem was that he didn’t know how to act like one. The spotlight terrified him. He has said of that time: “I thought I was having fun. But I was trying to do something that wasn’t really part of my personality. I wasn’t able to make myself feel comfortable in that environment, so I overindulged. It was like going to the dentist and getting a shot of novocaine. It numbed my mind. I no longer had the ability to reason.”

His sense of right and wrong dulled, Bernard was arrested four times in his three years at Tennessee (he bypassed his senior year for the NBA). Once, he was nabbed for attempted burglary, another time for prowling around a woman’s apartment. Both incidents occurred late at night when he was alone. King was acting out of fear and loneliness during a time when he needed attention, sensitivity, even trained guidance. But everyone around him was just too busy telling him how great he was and how happy he should be.

College treated younger brother Albert a bit differently. In his first game for Maryland, he scored only 13 points, and the Terrapin faithful were shocked. “Is King a Flop? A Hype-Job?” they asked. The pressure was intense, and Albert had a miserable freshman year, averaging only 13.6 points a game.

But he seemed to respond to the questions with the nonchalance of one accustomed to the spotlight. Besides, campus life was great, and the chicks were sexy. Indeed, Albert carried himself with a sense of such inner cool—he was playing only as hard as it took to win—that one could hardly wait until he broke those chains of reserve.

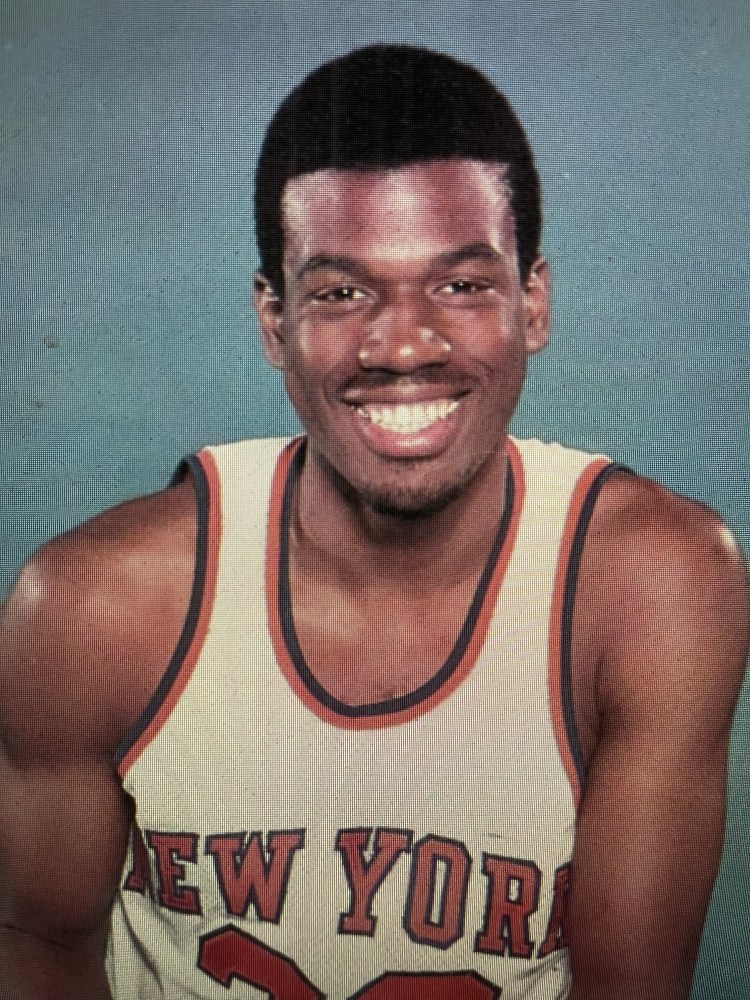

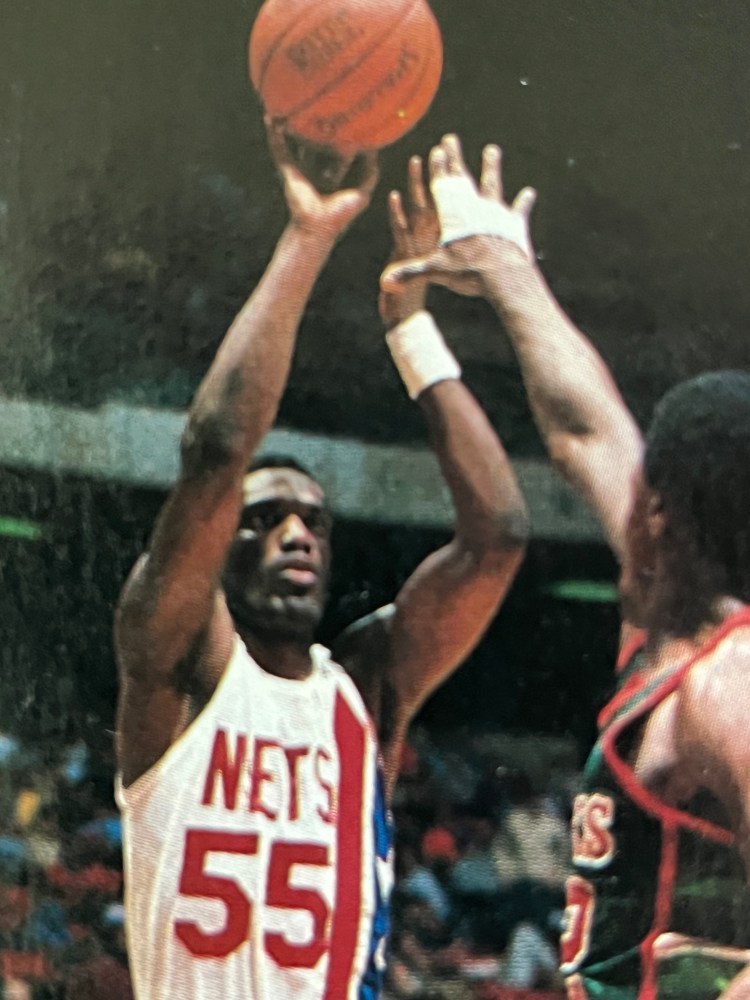

While Albert was surviving that awful freshman year, Bernard was playing brilliantly as the Nets’ first-round draft choice. He just barely lost out to Milwaukee’s Marques Johnson for Rooke of the Year honors, and he was disappointed that he didn’t win. “What do I have to do to get people to notice me,” he said angrily one night.

“Bernard was so intense when he played, it was frightening,” recalls Kevin Loughery, who coached King that rookie year. “The problem was, he was equally intense off the court—only he didn’t seem to have an outlet for it.”

King was a self-imposed loner who rarely hung out with his teammates. Life should have been great, but instead, it was one big air ball. Then, one morning in December 1978, Brooklyn police found King asleep in the front seat of his car with the motor running. “Figures,” thought those remembering his trouble times at Tennessee. Despite averaging 21.6 points for Jersey his second year, the Nets shipped him to Utah just before the 1979-80 season began.

It didn’t take long before trouble struck Bernard again. On New Year’s Day 1980, a Utah woman called police and claimed that King had forced her to disrobe and perform three acts of oral sex. Upon arrival at the scene, officers found King passed out on a bed, totally bombed.

Suddenly, Bernard King was faced with more than just expulsion from the NBA. He faced from five to 10 years in jail for sodomy, forcible, sexual abuse, and possession of cocaine. He had seemingly come to the end of the line, but Bernard received only a suspended sentence and a $2,000 fine after pleading nolo contendere to a lesser charge of attempted sexual abuse. Shortly thereafter, Bernard was admitted to an alcohol treatment program.

Meanwhile, Albert was becoming intoxicated by the success of a stellar junior season, in which he set a single-season Atlantic Coast Conference record with 674 points, led the Terps to a 24-7 record, and was named ACC Player of the Year and a consensus All-American. Before his 1980-81 senior year, Sports Illustrated’s annual College basketball issue displayed Albert with Mark Aguirre and Ralph Sampson in a rendering of Archibald M. Willard’s painting, The Spirit of ’76. In the picture, Albert’s eyes seem to sparkle with contentment, a feeling obviously enhanced when, at the end of that season, he was drafted by—ironically enough, the New Jersey Nets.

By 1980, Bernard was just beginning his comeback. After playing only 19 games during his nightmare year in Utah, his agent Bill Pollack called Golden State Warrior scout Pete Newell and asked if Bernard could attend Newell’s summer training camp. Reluctantly, Newell agreed, but soon found King was not a wreck that he would need to salvage.

“I knew Bernard had talent, but I didn’t realize how complete that talent was,” Newell says. “There wasn’t—and still isn’t—anything in the game he couldn’t do. But the thing that impressed me most about him was his willingness to work himself hard. He’s a very determined and hungry basketball player, which is the mark of the superstar.”

Eventually, Newell called Warrior coach Al Attles and raved about King. After talking with Bernard, Attles decided to gamble by trading Wayne Cooper and a 1981 number two pick to a Utah team only too happy to get rid of its problem child.

In San Francisco, King’s personal cable car climbed more than halfway to the stars: He was named the league’s Comeback Player of the Year, compiling a 21.9 point average and a career-high .588 shooting percentage in 81 games. “Bernard was everything you could want from a player,” Attles remembers. “He was a leader, his attitude was great, and he was one of the most-competitive players I ever coached.”

Perhaps Julius Erving summed up King’s attitude best that year when he said, “It seems like he was playing for his life, and he just possibly was.”

Three years later, Bernard is a New York Knick team captain, having signed as a free agent after the 1982 season. Albert, of course, is still playing for New Jersey, bouncing back and forth from coach Stan Albeck’s bench. The fact that they are both playing professional basketball in the metropolitan area is still the only thing they have in common.

“Bernard’s game is based mostly on strength, while Albert’s is founded on finesse,” says Lakers assistant coach Dave Wohl. “Another thing: Bernard is a hungry player. When his team is up 20, he wants them up by 30. He has that killer instinct. It seems that Albert doesn’t. When his team’s ahead, he appears content just to keep it that way.”

Some other expert assessments:

Seattle SuperSonic coach Lenny Wilkens: “The key is concentration. Bernard’s is total, a 100 percent. Albert, well, he tends to wander.”

Indiana Pacer coach Jack McKinney: “When the game on the line, the Knicks now know they can go to Bernard, and he’ll take it to the hoop and score or get fouled. The same isn’t true of Albert.”

The bottom line? Bernard is a spit-in-your-hands, roll-up-your-sleeves, blue-collar worker. Albert’s more a white-collar guy—the kind of a player who can get by purely on talent. In Bernard’s case, his intensity is best illustrated when he catches the ball on the break. His eyes grow wide; his jaws are steeled in concentration. He becomes a runaway freight and a guided missile. Nothing is going to stand in his way. So, he explodes toward the basket and slams the ball down the throat of anyone who’s ever denied him his due.

After the recent All-Star Game, in which Bernard scored 18 points and played magnificently, he told reporters, “It’s nice to know I can handle myself with the best. It’s good for my confidence.”

That comment out of the mouth of a legit superstar, who a couple of days later would become the first NBA player in 20 years to score 50 points on successive nights. Obviously, Bernard still doesn’t believe he’s as good as people say he is. Or maybe—although this would really be hard to believe—he doesn’t think he’s as good as he could be.

The best thing about Bernard King is that his dazzling talent—his game takeovers, jukes and jams, especially his astonishing leaping, driving midair stuff—is underscored by a rare ability to inspire his teammates to levels they couldn’t achieve on their own.

Albert King has yet to exhibit that kind of special ability. While Bernard hungers to prove—and validate to himself—his greatness, perhaps Albert, who has been told he’s great for so long, doesn’t feel he has to prove it anymore. Least of all to himself.

By all accounts, Albert is still the polite, gracious kid he always was. The pros haven’t changed him one iota. The same isn’t true for Bernard. He’s changed dramatically. He’s now happily married, has a daughter, and has more confidence socially. “A much more contented individual,” says Ernie Grunfeld, a teammate of King’s back at Tennessee and now with the Knicks. “Plus, he’s developed into a fine leader.” Hence, his recent election as team captain.

Which brings us to something Albert did back in 1971. Though it was meaningful at the time, its message is more appropriate today. In his freshman year, a Maryland PR man asked him to fill out a questionnaire. One question was: “Who has been your primary inspiration in sports?”

Albert wrote: “My brother, Bernard.”