[In his 2016 book The Curse: The Colorful & Chaotic History of the LA Clippers, author Mick Minas chronicled the ups and mostly downs of this seemingly ill-fated NBA franchise over more than three decades. There’s plenty to tell, and Minas does so through more than 500 pages. Yet, the text makes no mention of Michael Brooks.

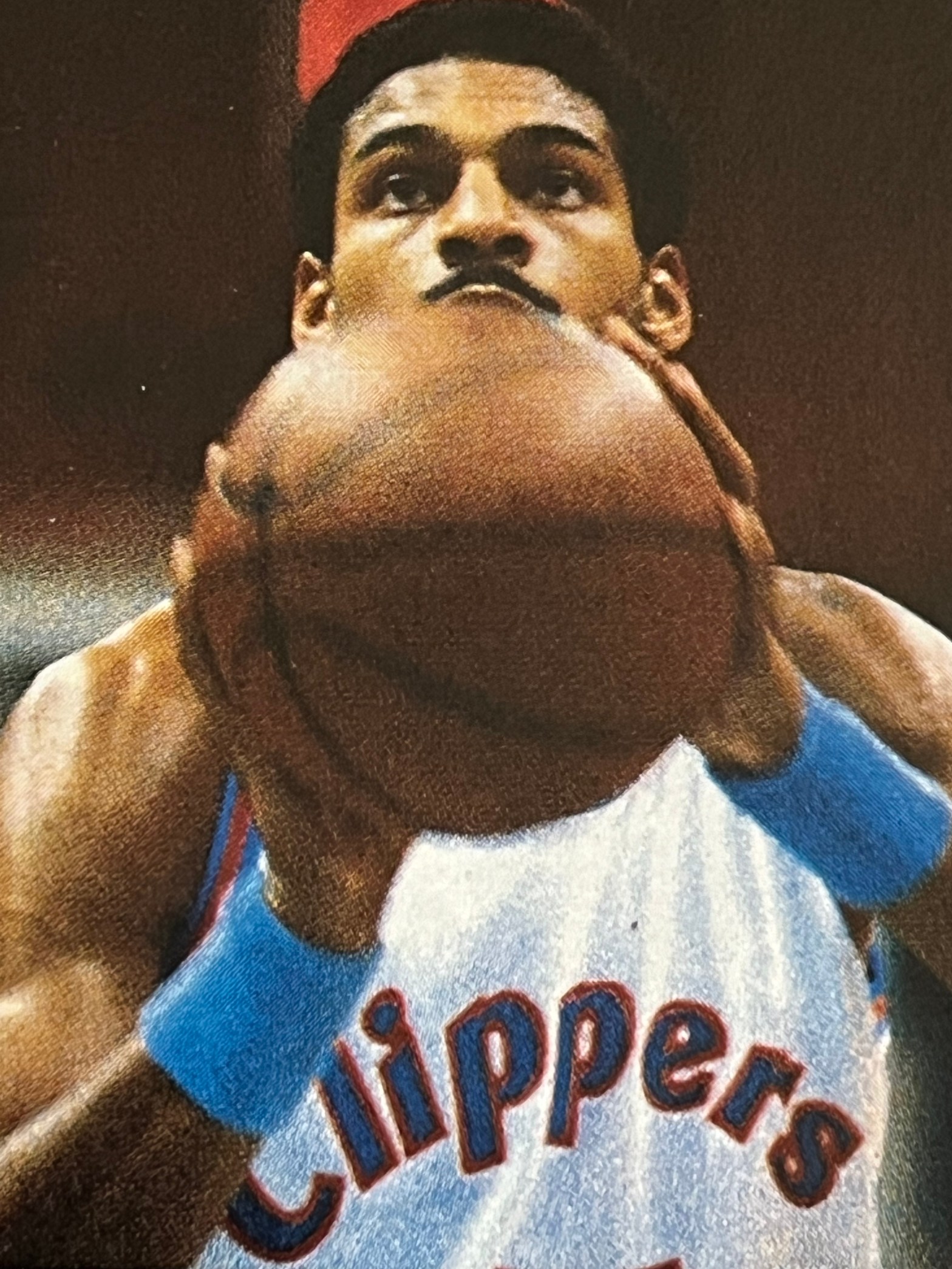

Michael who? In 1980, Brooks, the All-American forward from LaSalle, was the team’s top draft choice (ninth overall) and, from all indications, a major piece in the Clipper rebuild. Brooks, in NBA-speak, was “a warrior,” a versatile, high-energy stud who could battle inside against the best.

“After only one year, gen-u-ine NBA stuff,” an NBA commentator summed up Brooks. “Was only a matter of days into his rookie season last year when [coach] Paul Silas realized this was a starting forward. His emergence meant the end of the line for perennial Mr. Potential, Sidney Wicks. A very tough offensive player and imposing rebounder; vets learned quickly that the Clipper forward they’d prefer to defense wasn’t Brooks, but the comic Jellybean Bryant [yes, Kobe’s dad].”

Brooks wasn’t immune to The Curse, however. The first article below, published in the January 1982 issue of Basketball Digest, shows how the franchise’s losing ways wore on him as a rookie. So, did playing a new position. Brooks’ NBA challenge was to rise above the negativity, and Philadelphia writer Mark Whicker lays out how the Clippers’ prize rookie hoped to put mind over matter. Here’s the story.]

****

“Starting at forward for the San Diego Clippers tonight, averaged 14.7 points and 5.4 rebounds in his rookie year, living in condo-land splendor in La Jolla . . . from LaSalle College, Michael Brooks.”

Nice numbers. Nice address. From all estimates, a nice future.

“But in this league,” Michael Brooks says, with a smile full of insight, “things aren’t always like they seem. There are some positive things I knew about, and some negatives I didn’t know about.” And the negative for Michael Brooks in his rookie season was learning a new position on a 36-40 team.

And the wheels of his joyride through the NBA are spinning.

Brooks has lost none of the talent that made him an All-American, a force in the Pan-American Games, and a No. 1 draft choice. But that talent has been moved 15 feet from the basket, instead of kept beside it, where his strong rebounding hands and his touch in traffic used to live.

He was out on the wing much of last season when he shot .479 from the field and made the All-Rookie team. He flew downcourt repeatedly to shake loose from defenders, but the ball didn’t fly with him very often. So, he waited, quiet but restive, as guards Phil Smith, Brian Taylor, and Freeman Williams tried to carry the offense from afar.

It is not the game he dreamed of. It is not even the game that he brought to life at the start of last season, when he was averaging 20.5 points on December 1 and giving Darrell Griffith of Utah a persuasive argument for the Rookie of the Year Award.

“What happened to Michael happens to all rookies,” said Paul Silas, a rookie coach. “He was tough the first time around the league, and then people learned how to play him better. He was jumping over people early and scoring, but then they began sagging—and some of these guys can jump as well as he can.

“I’d like to see him put it on the floor a little more, challenge people, and also become a more complete player. His future is at small forward. But, overall, I’m very pleased with him. In time, he’ll be terrific.”

Brooks was the No. 4 scorer and No. 2 rebounder on the Clippers, whose habits make Silas admit, “coaching is a lot tougher than I thought it would be.” Brooks led the club in free-throw attempts and averaged nearly three offensive boards a game, too. But his field-goal percentage dropped from .505 in December to .479. His personal winning percentage—the stat Brooks has always cherished—has dropped more steeply.

After a walloping in Milwaukee, and one too many giggles in the locker room, the mild-mannered rookie spoke up. “I came out and said we didn’t have the right attitude,” Brooks said. “We weren’t business-like. I don’t mind hearing people laugh maybe 10 or 15 minutes after a loss, but they weren’t even waiting that long. The team had lost some close ones in a row, and we were drifting. I couldn’t really take it anymore.”

In the stands are . . . practically nobody. San Diego’s coffers are in the same cast that houses Bill Walton’s foot. “They’ll get more aggressively interested when the football season is over,” Brooks said. But there are, shall we say, a few distractions in the area.

The rookie spent his whole life in Philadelphia, a city where a power move and a reverse layup were parts of the culture. In his new town, they are footnotes. In his new league, they come harder. “The NBA is fun overall,” Brooks said. “It’s a learning experience. But you become a lot more aware of pressure.

“I’d never experienced what it’s like to see people traded, to see people waived, to see guys worried about what’s coming around the corner. It’s funny, the way they can see it coming. I see players on other teams who should be playing that aren’t playing because maybe the coach doesn’t like them or some other reason. It’s tough to go through life like that.”

Pressure was the reason that, on draft day, Brooks proclaimed, “I know I’ll learn a lot more basketball under Paul Silas than I would in Philadelphia under Billy Cunningham,” a remark Brooks still stands by, but clarifies.

“I just thought it would be easier in San Diego to get the playing time and learn at my own pace,” he said. “In Philly, I knew the 76ers would be winning, would feel the pressure to keep winning, and there wouldn’t be much time for teaching and learning. Plus, Paul was coming right off the Seattle roster as a player, and I knew he’d have a fresher outlook. That part of it has worked out for me.”

[But Brooks couldn’t outrun or outwill The Curse. The losing. By the end of the 1982-83 season, the same source quoted above, the one who touted Brooks as “gen-u-ine NBA stuff” sang a far different tune. “Biggest problem is that [Brooks] has always been more of a follower than a leader,” meaning the rookie who spoke up about the giggling in the locker room was now openly giggling—and groaning—about the franchise and the losing.

The source continued: “[Brooks] entered the pros with the reputation of being one of the nicest, most-coachable players ever. Has been greatly affected by life in San Diego’s animal house. Could probably stand a change of scenery and might blossom with a contender and some discipline.”

Brooks reportedly had followed his teammate and friend Jellybean Bryant in second guessing all of the brilliant moves in Clipper-land. Among those brilliant moves was drafting over Brooks, still only 25, and sending him to the bench to back up the talented younger tandem of Terry Cummings and Tom Chambers.

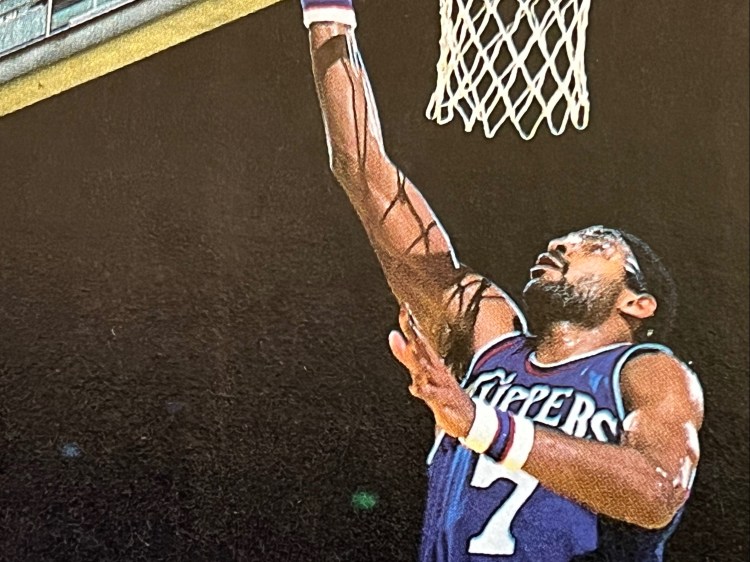

And yet, Brooks persevered through the chaos. In October 1983, his first NBA contract completed, Brooks signed a one-year deal for about $400,000, reportedly to “serve as incentive to bring his overall game up to a level it never reached under departed coach Paul Silas.” Brooks was now pegged as a tireless rebounder, a gritty defender, but a shaky outside shooter. That’s where he needed to improve. With Chambers now gone, Brooks seemed to have his chance to team with Cummings in the starting lineup.

Remember The Curse? Or maybe it was just tough luck. Midway through the season, Brooks blew out an ACL. Our next story, written by Bill Heller and published in the April 1988 issue of HOOP Magazine, fills in the blanks. The Clippers would waive Brooks, as he struggled to rehab and get his NBA career back on track. More than 35 years later, Brooks’ torn ACL illustrates just how far sports medicine has advanced in our day. The story shows how this now-common injury could derail NBA careers in the 1980s. In fact, Brooks never re-established himself in the NBA. He did later resurrect his career in France, where he relocated and got into coaching. In 2016, Brooks passed away at age 58 from complications of aplastic anemia.]

The pass was tipped, and Michael Brooks’ life would never be the same. The knee brace that he unstrapped after finishing a workout with the Albany Patroons, his third CBA team in little more than one season, covers the scar from his final game with the San Diego Clippers four years ago.

“We were playing in Cleveland,” Brooks said. “I stole the ball, gave it to Billy McKinney, and took off. He threw it ahead. Someone was behind me and tipped it. I tried twisting to get it. My knee just buckled. Nobody hit me. It was a freak accident.”

Brooks spoke easily, his voice showing little emotion from that night in Cleveland, February 4, 1984, when he was playing in his 293rd consecutive NBA game for the Clippers. “I hadn’t missed a game in three-and-a-half years,” he said. “I thought I was indestructible.”

Dr. William Curran, then the team orthopedic surgeon, remembers the moment which betrayed Brooks’ mortality: “I was listening on the radio. I remember going, ‘Oh-oh.’ They had to carry him off the floor.”

Subsequently, the forward, now 29, was carried into personally uncharted territory, a three-year test of physical and emotional strength, which nearly overwhelmed him. In knee injuries to athletes, rehabilitation is a confounding term, because it implies recovery and restoration, which is never certain. There are no guaranteed contracts for a man’s body, especially not for the intricate mechanism inside a knee.

Initially, Brooks thought he had hyperextended his right knee. Curran, however, found a torn anterior cruciate ligament. “It’s deep inside the knee in the center of the joint,” Curran explained. “It controls rotation of the shin bone on the thigh bone.” Curran also found torn cartilage outside the knee.

Curran labeled the torn ligament “a very serious injury. In basketball, the track record for recovering from tears of anterior cruciate ligament is not good because basketball is a transition game. You go from offense to defense in a second. You’re doing a lot of pivoting, turning, jumping in seconds. The rapid transition puts a tremendous amount of torque forces across the knee, a lot of stress and strain. There are a lot of tombstones of people out there, who didn’t come back from anterior cruciate ligament tears.”

Curran named Billy Cunningham and Doug Collins as examples. He said, “The jury’s still out” on Bernard King. Saying the same about Brooks was unnecessary.

The operation took three hours, a little longer than an NBA game. Brooks didn’t play professional basketball again for 34 months. He didn’t even want to leave his house the first few months following the injury. “The first six months after surgery were the hardest six months of my life,” Brooks said. “I got so depressed about being hurt, about not playing basketball. I didn’t want to be seen in public. Getting over the depression is by far the hardest part for me.”

He got over it, despite caving in to the depression and quitting therapy three months into his rehabilitation. He went back to therapy and made it part of the way back into basketball, even reaching the NBA last season for a pair of 10-day contracts with the Indiana Pacers. “It was a situation where I said, ‘My God, I did it.’ A lot of people thought I couldn’t. I worked so hard,” he said. “It was an emotional high for me.”

The feeling dissipated when the Pacers let him go. Brooks retreated to the CBA, where he has staged another campaign to return to the NBA. Understand this about Michael Brooks: Challenges motivate him.

They have since he started playing basketball in Philadelphia. That city has produced a string of schoolboy legends, but Brooks was not one of them. “I was the 12th man on the freshman team,” Brooks said. “I told everybody I’d be starting on varsity next year. They all laughed.”

Brooks started the next three seasons for West Catholic High School for Boys. His career did not elicit a flood of college offers. Only one team outside the city, Providence, came courting. The competition for Brooks’ skills was LaSalle, Villanova, and St. Joseph’s. “I wasn’t that highly recruited,” Brooks said. “I wasn’t that good, plain and simple. The older I got, the better I got. I just developed later.”

During Brooks’ sophomore season at LaSalle, Notre Dame coach Digger Phelps said, “I’m surprised the 76ers haven’t scooped him up already.” The same winter, Villanova coach Rollie Massimino called Brooks “the best player in the East. There aren’t many better players in the country.”

Brooks already had established himself the previous season, setting the tone for a remarkably consistent college career by averaging 20 points and 10.7 rebounds. In each of his four seasons at LaSalle, Brooks averaged at least 20 points and 10 rebounds.

Versatile enough to play big guard as well as forward, Brooks used his lean, angular, 215-pound body to slash away inside, where he displayed surprising power. His knowledge, and feel for the game or surpassed only by his intensity. “He was a strong, aggressive, exceptionally quick-running forward,” said Loyola Marymount coach Paul Westhead, who coached Brooks his first three years at LaSalle. “He’d rebound the ball, pass off to a guard, take off like a locomotive, catch the ball in midflight, and slam dunk at the other end. Locomotive is the perfect word for him.”

Brooks averaged 24.9 points and 12.8 rebounds his sophomore season, then 23.3 points and 13.3 rebounds the following year. Yet the Explorers finished a tepid 15-13 in Westhead’s last year at LaSalle.

Lefty Ervin took over in Brooks’ senior season, and Brooks led the Explorers to a 22-9 record, including an eight-point loss against Purdue and Joe Barry Carroll in the first round of the NCAA Mideast regional. Brooks’ senior numbers were 24.1 points per game (with a high of 51 against Brigham Young, the most points by any college player in the country that season) and 11.5 rebounds per game. The awards, including All-American and Player of the Year in the East, followed naturally.

If there had been any doubts of Brooks’ ability, they were dispelled after Brooks’ junior year, when his 17-point average helped the United States win the gold medal in the Pan-American Games for coach Bobby Knight. After the Games, Knight wrote of Brooks: “If I were allowed to start my own team tomorrow and pick anybody that I chose, the first person I would pick is Michael Brooks.” Brooks said of Knight, “He brought the player inside of me out.”

Brooks also was a member of the 1980 U.S. Olympic team, which stayed home because of the American boycott. The Olympians played NBA teams instead, giving Brooks valuable experience for his next challenge, the NBA.

The San Diego Clippers made Brooks their first round 1980 draft selection and the ninth player taken overall. With the Clippers, Brooks had to adjust to losing. “I was on the team that lost 19 straight,” Brooks said. “It’s hard. After a while, you just become numb to the losing. You just go out there and play. Win or lose, you can’t change your attitude. You just have to give 100 percent. We played as hard as we could. Just because you’re on a losing team doesn’t mean you’re a loser.”

Brooks had a good rookie year, averaging 14.7 points and 5.4 rebounds. The following season, Brooks led the team in assists (236), games (82), minutes (2,750), and field goal attempts (1,066) while improving both his scoring (15.6) and rebounding average (7.6). His shooting percentages, .504 from the field and .757 at the line, were the highest of his NBA career.

Brooks’ averages, 12 points and 6.4 rebounds per game, dropped his third season. He never got to complete his fourth.

Dr. Curran saw Brooks the morning after the injury. “I gave him several options, operative and nonoperative,” Curran said. “We decided to operate the following day. We took the torn part of his cartilage outside of the knee and repaired and reinforced the cruciate ligament tear with a tendon graft.”

Who would repair Brooks’ psyche? “I told him the prognosis was guarded,” Curran said. “I tried to be as positive as I could be. I wanted to be honest with him.”

Honesty to himself, in admitting the severity of the injury, would be one of many obstacles for Brooks. “I thought I could work one month, and that’d be it,” Brooks said.

That wasn’t it.

Brooks begin rehabilitation every other day for three months. Then he stopped. “It was difficult for Michael because he got so depressed,” Curran said. “He just quit therapy. He absolutely quit therapy. He didn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel, and if he did, it was a freight train coming down on him. He was discouraged and depressed. He said he needed some time to think about things.”

Brooks knew he was hurting. “I went through the same thing everyone goes through—depression,” he said. “There were peaks and valleys. One day, it was better; the next day it wasn’t. At first, there was no light at the end of the tunnel. I wasn’t mature enough to accept the responsibility. It was my responsibility to get back playing. I wasn’t doing my job. The doctor did his.”

Then, suddenly, Brooks went back to therapy. “Two to three months later, the therapist next-door called me and said Michael had arrived,” Curran said. “I said, ‘Great.’ From then on, he just took off. His state of mind was better. He was able to accept the down days.”

But he wanted the up nights—the nights of basketball—again. So, he kept working. The Clippers invited him to training camp in the fall of 1986 only to waive him when his knee showed weakness during various strength tests. Bill Musselman, now coach of the Albany Patroons and former coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers, was coaching Tampa of the CBA last year. “My son, Eric, saw him playing in San Diego in a recreation center, and he said he was ready to play,” Musselman said.

Musselman signed him and watched with delight on December 4, 1986, when Brooks had 26 points and 17 rebounds in Tampa’s 137-114 opening night win against Savannah, Brooks’ first game in nearly three years. “He rehabbed for two years,” Musselman said. “You have to respect that. He played hard right away. He went full speed. He dove for loose balls. He knows the game, and he’s very team-oriented. He’s just a fine person. He’s a winner.”

Brooks averaged 22.7 points, with a high of 40, and 10.8 rebounds in 12 games with the Thrillers before Indiana signed him to the 10-day contracts on January 1, 1987. “The first team we played against was the Clippers,” Brooks said. “Mentally, I felt like a rookie.”

Brooks played in 10 games with the Pacers, averaging 3.3 points and 2.8 rebounds. He returned to the CBA for eight games with Charleston last season. Albany acquired his rights in a trade in August, less than two months after hiring Musselman to replace Phil Jackson, now an assistant coach with the Chicago Bulls.

The brace—(“It looks heavy, but it isn’t, eight ounces,” Brooks said)—is a daily reminder of what he’s been through, where he has been, and where he fully intends to return: to the NBA. “I’m still young,” he said. “I’m not going to give up until I look myself in the mirror and say I can’t play anymore. I love the game so much.”