[Bill Cartwright is best remembered as the highly skilled, though at-times awkward, seven-footer on the championship Chicago Bulls teams of the early 1990s. Cartwright led with his elbows and, at times, rebounded like a wrecking ball inside. His declining athleticism, a product of age, big frame, and an almost career-ending foot injury, still gets debated. His toughness? Almost never.

Wind the clock back to 1980—following “Mr. Bill’s” impressive rookie season with the New York Knicks—and the talk was ALL about Cartwright’s toughness or lack thereof. Keep winding back to Cartwright’s high school and college careers. Same story.

Having grown up in 1970s Sacramento surrounded by the oohs-and-ahhs of Elk Grove High School’s Bill Cartwright, I’ve always smirked at the toughness debate. Of course, Cartwright was tough enough “to make it big.” He just had to stay healthy and learn along the way how to lead with his elbows effectively.

But, above all, Cartwright was born under a lucky star. He grew up the tall son of a hardworking farmhand just outside of Sacramento, then a basketball backwater compared to Oakland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Heck, even Fresno and Stockton for that matter. About that lucky star. Cartwright was discovered as a young teen by Dan Risley, one of only a handful of Sacramento high school coaches with the time, energy, and all-out drive to mentor him and hone his court skills. Most prep coaches back then wouldn’t have bothered enough to bring out Cartwright’s greatness. Harsh, but I saw it firsthand in my part of the city. That’s why Sacramento was a basketball backwater.

The hard-driving Risley also built a top basketball program, where Cartwright could play the game at a high level. Again, a rarity in Sacramento back then. And to his credit, Cartwright was a star pupil who put in the extra time in the gym to learn how to play the pivot. All of these factors made Cartwright a winner. Hard times might come, but Cartwright was way smart enough and driven to figure it out. He was born under a lucky star.

In this article, from the December 1980 issue of the magazine All-Star Sports, writer Mike Weber talks a little about Cartwright’s lucky star and much more about that “his Mr. Nice Guy image.” I’ll follow up afterwards with an article from May-June 1984 issue of the magazine New York Sports, that compares Cartwright with New Jersey’s Darryl Dawkins. It’s the same old about Cartwright, who time would tell was tough enough.]

****

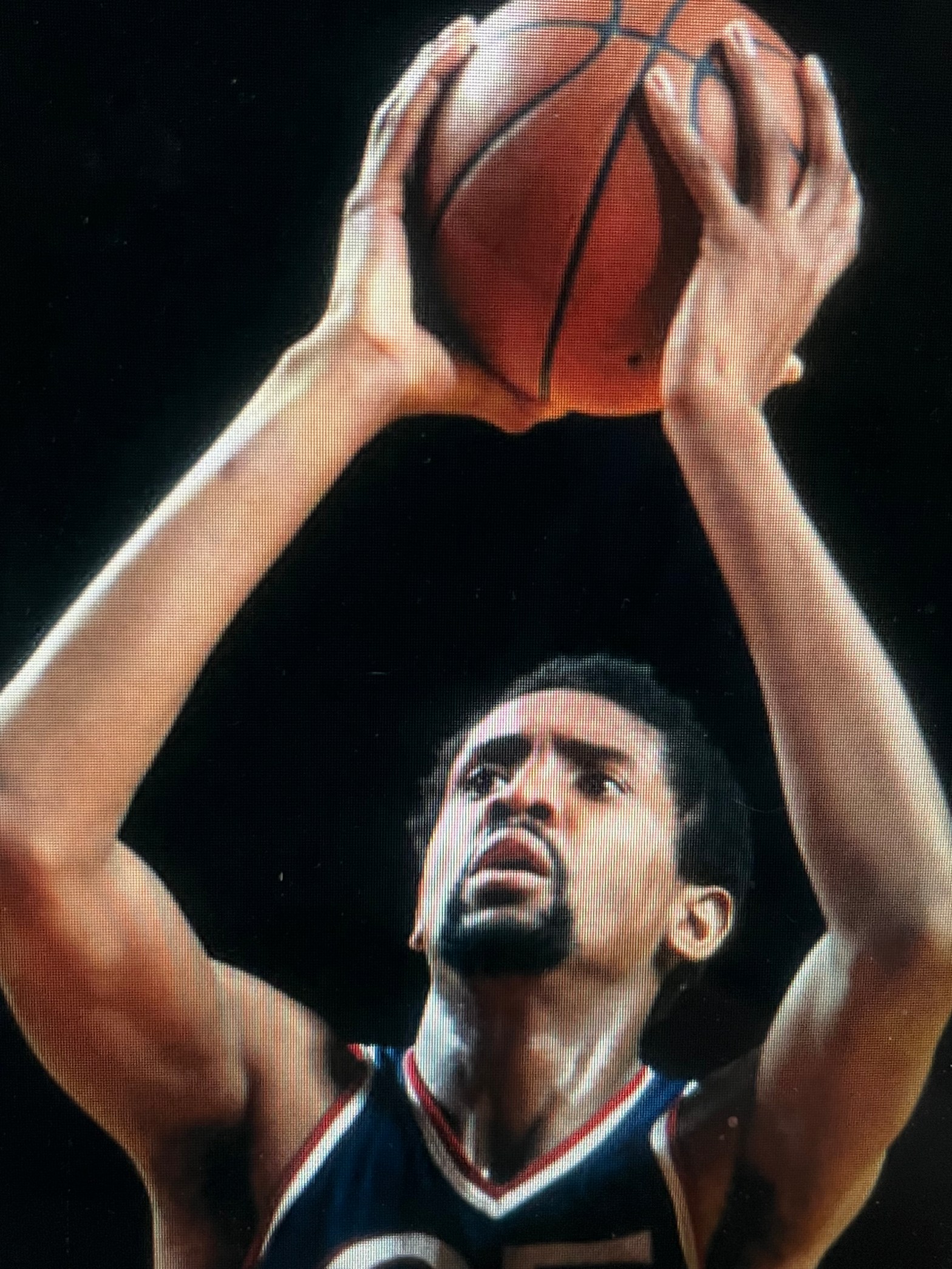

There is the body; oh yes, there is the body. Big. Forbidding. Still young enough to be molded, but mature enough to make you not want to run into it twice if you have to run into it once. There is also the mind. Inquisitive. Attentive. Keen enough to know there is more to basketball than natural talent, open enough to sometimes allow basic instincts to rule.

This is Bill Cartwright, a man large in body and mind, who, if he one day synchs one with the other consistently, may become a frightening force in professional basketball.

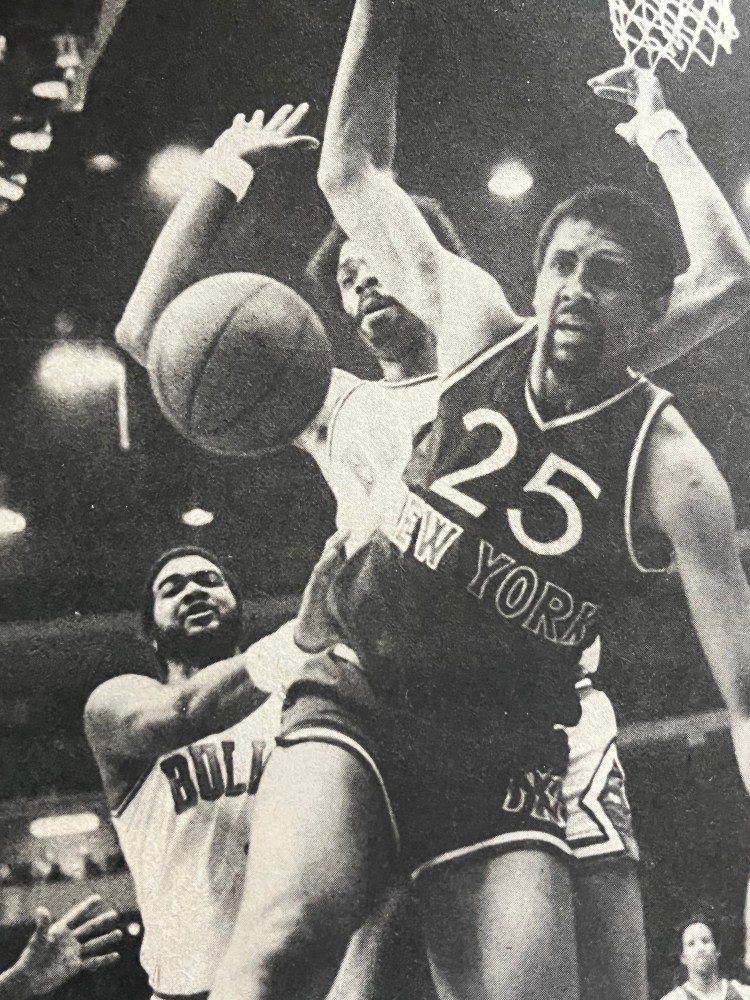

This is Bill Cartwright, all 7-feet-1 and 255 pounds of him. This is Bill Cartwright, who did not wilt beneath an incessantly shining spotlight during his rookie season with the New York Knicks. This is Bill Cartwright, the best Knick center since Willis Reed. This is Bill Cartwright, who Reed indicates may become the best Knick center, period.

“Three years, four years from now,” said the former Knick great, “Bill Cartwright’s impact—his importance on the outcome of a game—will be much greater. He’ll know the game on a different level. He’ll think the game on a different level. He’ll see the game on a different level.”

During his one NBA season, he did those things on different levels than most players. He analyzed himself, his actions, and those around him. He already knew “how.” He wanted to know “why.” “Basketball is a thinking man’s sport,” insists Cartwright. “You have to think to really understand it. A lot of guys play without really understanding what they’re doing out there.”

Bill Cartwright feels he knows. Seems he has had the right people teaching him to know. Now, of course, there is the Knicks’ resident genius Red Holzman, imparting the knowledge of a life spent amidst tall people, short pants, and hard courts. But Cartwright began learning his trade long ago, back before he dreamed that he would one day be the cornerstone of the franchise which many regard as the NBA’s most important.

****

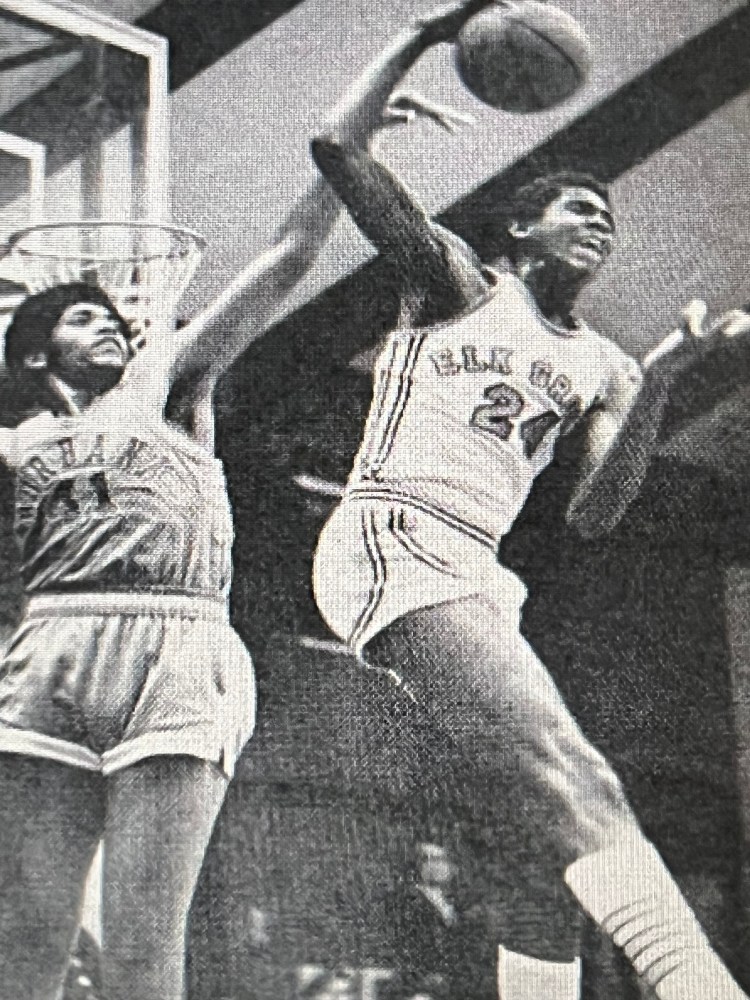

It is 1972 and a lead-bottomed high school freshman named Bill Cartwright is starting to cause a stir on the West Coast. Mr. Bill is only 6-feet-6 and his weight seems to be distributed wrong. But there is that marvelous ability to shoot a basketball.

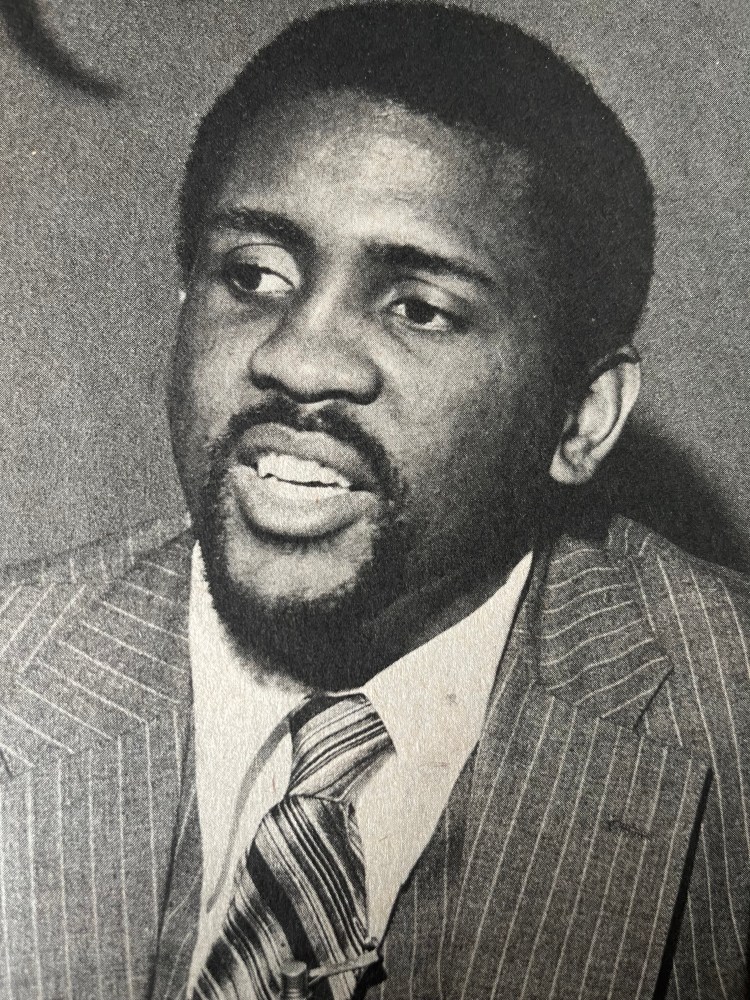

Dan Risley remembers. He was the coach at Elk Grove High School, just south of Sacramento, and he kept hearing about Cartwright. What he heard made him burn to see this local flash play a game. What he saw made him wonder why he bothered. “He had the flu,” Risley recalls. “After the jump ball, he went to the bench for the rest of the game. It was a nightmare.”

Fortunately for Risley—and perhaps for Cartwright as well—Risley didn’t give up. He went back to see Cartwright, and each time he liked more of what he saw. Since he was going to see plenty of Cartwright, beginning the following fall at Elk Grove High, Risley set about polishing what was then a large—a very large—uncut gem.

“I contacted Bill’s parents in the spring, and I told them if Bill would come down to the high school after classes and work with me, he’d have an incredible future,” said Risley.

There was one potential problem with the future. It was the present. Cartwright’s father James was a farm laborer, and he was supporting Mr. Bill, a wife, and six daughters. The work that James had in mind for Bill had nothing to do with basketball.

But there was something about the way Risley talked to the Cartwrights, something in the way he was so sure that this youngster would one day be a basketball force. Thus did the tutoring of Bill Cartwright begin in earnest.

“It was very definitely a sacrifice on their part,” said Risley. “I told his parents if they let Bill play during the summer, I guarantee he’d have a college scholarship. In essence, they gave their son to me to be transformed into a basketball player.”

The transformation was not without its painful moments. Risley pitted Cartwright against a 6-feet-8 sophomore Terry Saufferer. Now, you may not remember Terry Saufferer. But Bill Cartwright does. What he remembers most of all are the elbows of Terry Saufferer. Two hours a day, day after day, Cartwright vs. Saufferer, Saufferer vs. Cartwright.

“For the first two months,” Risley revealed. “Terry would practically beat him to death. Bill would leave the gym with black and blue marks and bloody noses.”

But each day he left the gym, he left it a bit more talented, a little more sure of himself, a tad better prepared to deal with what lay ahead. He would grow three inches during that summer, and by the time he was a junior, he was seven-feet tall. “It was then,” said Risley, “that the carnival began. But we didn’t put Billy out as a sideshow.”

What Risley did was protect him. Every college that was anything and any college that wanted to be everything wanted Bill Cartwright. While Cartwright scored points and collected awards, Risley met the procession of recruiters. Eventually, during Cartwright’s senior season, he and Risley narrowed the choice to three California colleges—UCLA, USC, and USF.

USF?

If the initials didn’t register as quickly as the first two sets, be not embarrassed. The University of San Francisco just isn’t as well-known as its other Golden State brethren. It was that fact which led Cartwright to enroll there. That and coach Bob Gaillard, and the fact that Risley was hired as an assistant coach.

Cartwright felt that, at USF, he could maintain his own identity rather than become another Bruin or Trojan. So, USF it was, where he led the Dons to an 85-22 record and three Western Athletic Conference titles.

Risley helped guide Cartwright through the college experience . . . the experience of being a marked man from Day 1, the experience of being expected to produce a national championship, the experience of being the most-dominating college player of his years.

Perhaps these experiences prepared him for the experience is to come. It mattered little which pro team would select him in the draft, he would be scorched by the spotlight. When the Chicago Bulls did the Knicks a favor, selecting David Greenwood and leaving Cartwright to New York, the heat of the spotlight intensified.

The Big Apple had turned sour on saviors such as Spencer Haywood, Bob McAdoo, and Marvin Webster. But Cartwright, make no mistake about it, was supposed to save. He was to restore order to the middle of the Knicks’ attack, give them something solid on which to build. There were some who doubted he could do it.

The critics would tell you that Cartwright was too heavy, that he had been very sheltered for so long, that he would be ill-equipped to handle pressure, that, despite his awesome size, he wasn’t very tough. You still hear some critics say those things. But they don’t say them as often or as loudly. Cartwright’s first year performance is why. In another season, in a season without a Larry Bird or a Magic Johnson, Bill Cartwright would be starting this season as last season’s Rookie of the Year.

He averaged 21.7 points per game, leading the Knicks while ranking 13th in the NBA. He made 54.7 percent of his field-goal attempts, and averaged 8.8 rebounds, topping his team in both of those categories. He did not amass these totals flamboyantly; indeed, his on-court demeanor is the same as it is off—controlled, subdued, effective, and efficient.

He will shatter no backboards. He will perform no windmill dunks. What he will do, however, is produce. “It doesn’t matter if you dunk it, lay it in, or if you kick it off your foot,” says Cartwright. “It’s only two points, anyway.”

Cartwright’s cool earns him supporters as well as detractors. The detractors, of course, say that you must be mean to play the NBA’s meanest position, where angry elbows are to be answered with incensed forearms. Cartwright is not mean; never was, probably won’t ever be.

That’s fine with Knick general manager Eddie Donovan. “The thing I like best about him,” he said, “is that if he gets whacked, he doesn’t say a word. He doesn’t take any crap, he just comes back the next time and gets in his shot.”

Oh, that shot. That sweet fallaway, turnaround shot from the corner. Try to stop it. Try. Too late, it’s already basket-bound. Often, only the Knicks themselves could stop Cartwright by failing to get the ball into him. So many times, Mr. Bill would lumber through the lane, looking for the ball, wanting the ball, not getting the ball. The next time downcourt, Cartwright would do it all over again.

“Remember the way Willis would stand in the middle and wave his hands for the ball?” asked Donovan. “Bill is Willis all over again that way. They have the same quiet charisma about them, on and off the court. The big difference between them is that Bill is four inches taller than Willis.”

Adds Holzman: “When we drafted him, I felt he would be good. But I did not envision him being so good so soon.”

He became very good very soon, just as soon as he decided that he really could play with people named Unseld and Malone, Abdul-Jabbar and Dawkins. His self-confidence soared after an early season meeting with Darryl Dawkins and the 76ers. Double-D had the ball down low and turned to shoot over Cartwright. Suddenly, Cartwright jumped over Dawkins and rejected the shot. “I stepped back, looked at him, and knew I could play in this league,” said Cartwright. “All modesty aside, I feel like I can compete with these guys. I can play with anyone.”

That fact was not lost on those against whom he played. Veterans do not like being outplayed by rookies, and they will do whatever they can—within the rules or without—to gain an advantage. Cartwright had the additional problem of being labeled, “a very nice guy.” After all, how fearsome can a man be who married his junior high school sweetheart, who drinks eight bottles of Coca-Cola a day, who just loves music from the 1950s, and who devours hours of soap operas?

So, Cartwright felt more than his share of jabs and elbows, of punches and shoves, getting stares and dares that would crush the faint of heart. Cartwright didn’t like it, but he took it. “You get tired of them beating you to death,” he said. “You get old real fast.”

“Old” has a negative connotation. What Cartwright got was mature. The Knicks are counting heavily upon a mature, though still only 23-year-old, Cartwright to lead them not only near, but into, the playoffs this season.

Though Cartwright’s rookie year was an unqualified success to most observers, Cartwright would disagree. Yes, he established himself as a future star; yes, he may become a true force in the league; yes, given his statistics and the respect which they generated, Cartwright has reason to be satisfied.

But there was one statistic which took the edge off everything. When it came to bottom-line time, Mr. Bill and the Knicks were found wanting. Wins 39; losses, 43; playoff berths, none. “What difference does it make how many points I score?” Cartwright mused. “If you lose, it’s pointless. What I want to prove is that I can play with the Knicks and win some games. I wouldn’t even want to play if [scoring] is all that counted.”

That kind of selfless thinking is heresy to some NBA players, admired by many observers, and a bit confusing to one Sheri Cartwright. Bill’s wife, a former cheerleader and a participant in individual, rather than team, sports, thinks things have gone just smashingly. And why not? There is a luxury high-rise apartment in New Jersey during the season and the recently purchased home in California for when the ball stops bouncing. And speaking of bouncing, there was the couple’s child, Justin, born last March 23.

Sheri seems to be the anchor for Mr. Bill . . She is her man’s best fan and can be found at virtually every Knick home game. “I cheer,” she said, “but I don’t blow whistles like the baseball players’ wives do.”

She may have even more to cheer about this season. Now that management knows what Cartwright can do, it has begun molding its team around him. There are more plays for Cartwright, specific instructions to get the ball to him, a teamwide confidence that if he gets the ball that he will score.

There are a few things which observers feel Cartwright could do in return for the Knicks’ faith. First off could be some pounds. He did reduce from a college weight of about 265 to 250. But many felt his poundage increased as last season wore on. Critics feel that the excess baggage, which seems to be packed into his caboose, keeps him earthbound when he might otherwise soar for rebounds. Cartwright just shrugs his shoulders, swigs another cola, and gives his best here-we-go-again look.

“What I weigh doesn’t matter,” he said “It wouldn’t matter if I weighed 500 pounds or 5,000 pounds.” He added that he must have been in pretty good shape last year because he averaged about 39 minutes per night while playing in all 82 games.

Knick management, unlike its neighbor across the Hudson River in New Jersey, makes little to-do about Cartwright’s weight problem. When guard, John Williamson played for the New Jersey Nets last year, he ate himself into coach Kevin Loughery’s doghouse, was unofficially suspended for 20 games, and was eventually traded. In the meantime, the team was derided, Williamson was ridiculed, and the Nets finished behind the Knicks in the Atlantic Division standings.

And then there is the matter of Mr. Bill’s temperament. Many feel he must get mean. Like Willis Reed. Now that man was mean.

“I don’t like the word ‘mean,’” said Reed, who may not like the word, but personified it as the Knicks’ 6-feet-9 center. “I like the word, ‘competitor.’ That’s what you look for in a player. A guy, when he loses a big ballgame, it really hurts. Not a guy who goes in the shower, gets dressed, and doesn’t feel anything about it.”

Reed maintains that Cartwright is not “too nice.” The problem comes when people compare his style to Reed’s. It is not a valid comparison, says Reed, because “I had to be more physical than Jabbar or Chamberlain because I didn’t have the height. If Wilt Chamberlain used his body like I used my body, there wouldn’t have been anybody to play against. I think Cartwright plays tough.”

In truth, he could play a little tougher, he could rebound a little more, he could weigh a little less. But among players in the NBA might not do a little more here or there? How many could not stand improvement? But how many do stand 7-feet-1?

“A kid like Cartwright, you couldn’t pass up,” said Donovan, the Knicks’ GM. “They don’t come along very often. A great shooter, great hands, good attitude, team player. And, as great a coach as Red is, he can’t teach a kid to be 7-feet-1.”

[Fast forward three seasons, and the toughness debate continues. Here’s writer Richard O’Connor in a story headlined, “Dawkins or Cartwright.” As mentioned above, O’Connor piece ran in the May-June 1984 issue of the magazine New York Sports. I’m adding this article only to illustrate just how toxic life could be in New York and New Jersey if the poison pens didn’t consider you tough enough. Remember: Cartwright learned the game getting his nose bloodied in the Elk Grove gym. Tough he was. But Cartwright made his name and money scoring points as a skilled, go-to big man featuring polished, turnaround post moves. Time, a serious foot Injury, and the arrival of Patrick Ewing in New York would make Cartwright grow into a more complete post player . . . in Chicago.]

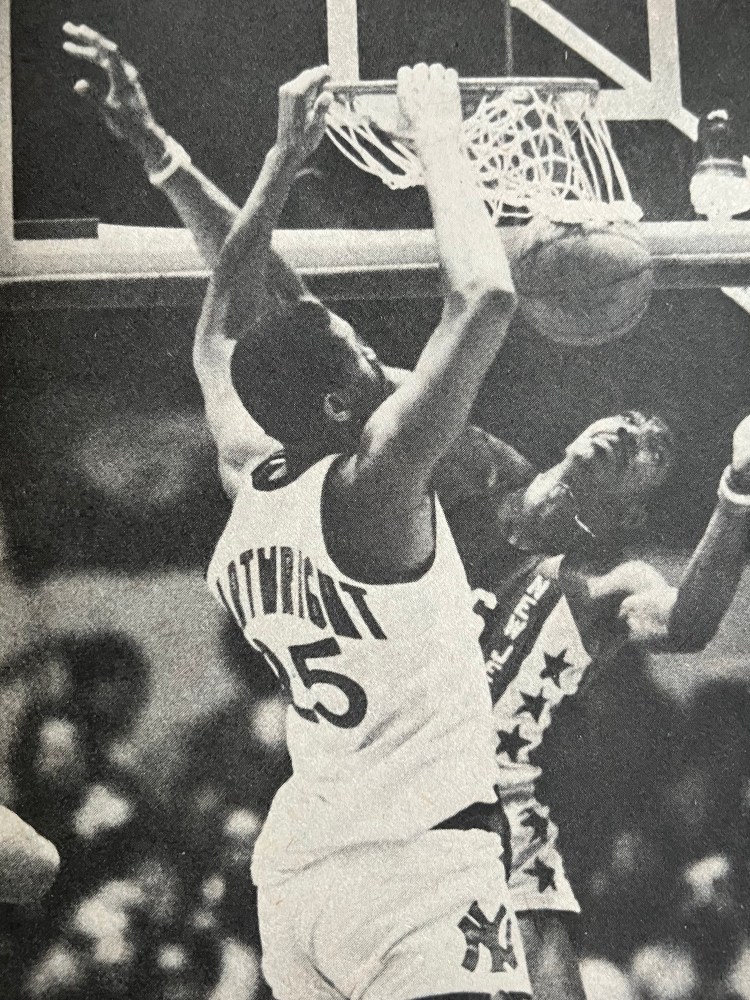

When the editor of this magazine suggested I evaluate the talents of Knick center Bill Cartwright and Net center Darryl Dawkins for this column, my gut reaction was, “Are you kidding? The question isn’t who’s better. It’s who’s worse!”

And I was not being facetious. Lord knows I have spent many a painful evening in both the Garden and Byrne Arena watching Cartwright and Dawkins drift up and down the court, content to get their points, but rarely dominating the action, and never—NEVER—taking a game by the throat and choking it to death. What makes it so frustrating is that both players, each in his own way, possess wonderful physical skills. But those skills are kept dormant by the absence of mental toughness. To put it simply: Neither wants to pay the price it takes to be a great NBA center.

It’s common knowledge that Cartwright and Dawkins go to the glass as much as teetotalers go to alcohol. But dig this statistic: Last year, both players finished in the bottom three among healthy NBA centers in rebounding, averaging 7.1 and 5.2 respectively. That means they were outrebounded by lightweight NBA centers like Dave Corzine, Cliff Robinson, Dan Schayes, and Wayne Cooper, not to mention small forwards like Gene Banks, Jay Vincent, and Jeff Wilkens, and guards T.R. Dunn and Magic Johnson. Just disgraceful.

I’ve long held the deeply rooted conviction that great NBA teams reflect the mood and personality of their big men. If a team’s center is an intimidating force—an Abdul-Jabbar, a Walton, a Russell, a Chamberlain, a Malone—he will not only dominate the flow of action, but he will also bring together a group of disparate talents.

After the Knicks won the 1969-70 NBA championship, I asked Bill Bradley what made the team’s chemistry so special. “Willis Reed,” he said without hesitation. “Ever since he became our center, he gave us a presence inside that was equal to his dominant physical stature. He was, if you will, an enforcer.”

To call either Cartwright or Dawkins an enforcer would be like calling Mr. Rogers a nasty sonavabitch. In Dawkins’ case, he seems content with becoming the Emmett Kelly of the NBA—a vast, laughable sideshow. Cartwright, on the other hand, is perhaps the only NBA player who would reject the advice of a charismatician. Even Nate Bowman did more to stimulate Knick fans than InvisiBill does.

“To be honest, I wouldn’t trade for either one,” says one NBA coach, who prefers to remain anonymous. “Dawkins is a court jester, a goddamn media hype job without much substance, while Cartwright is the biggest pussycat since the Cowardly Lion. Neither one has ever really spit in his hands, rolled up his sleeves, and worked overtime.”

Very true. But both exhibit deficiencies far beyond mere laziness. Let’s start with Dawkins.

Dave Wohl, assistant coach with the Los Angeles Lakers, is a close friend who has long debated with me about Dawkins. According to Dave, my problem is that I look at Dawkins and expect too much. “You see the awesome body, and you want spectacular things to come from it,” Dave argues. “Did you ever think he may not be capable of more?”

I would agree with that assessment, except for one thing: I have seen Dawkins play truly inspired basketball; I have seen him on nights when he was punishing the boards, making strong power moves inside, and running the lanes as if he were being chased by a street gang. On those evenings, what he did was difficult and beautiful—it was poetic, really—and for the moment my faith in the potential of Darryl Dawkins was restored.

The problem is that for every great Dawkins performance, there are four in which he stinks the joint out. Granted, he always gets his points—there’s never been a question about Darryl’s scoring ability—but he seems to want no part of rebounding. His lack of concentration, his lackadaisical defense, his stupid fouling, and his overall inconsistency nearly drove former coaches Billy Cunningham and Larry Brown to the nuthouse.

To be fair, Dawkins has played much better under current Net coach Stan Albeck. Says Albeck: “Darryl has made good strides this year. His points and rebounding averages are better, and because we have him in the low post, he’s less likely to throw up a fadeaway 20-footer.”

Cartwright, on the other hand, has barely improved his game since his impressive rookie year when he averaged 22 points and 8.5 rebounds a game. A large part of Bill’s problem is self-delusion—he thinks he’s playing terrific ball. The fact is, aside from being the most-passive person since Gandhi, Cartwright is an absolute cipher on defense. “He’s no problem whatsoever to score against,” says Washington Bullet center Jeff Ruland. “All you have to do is take it at him strong.”

The bottom line on Cartwright is this: He simply refuses to kick ass night after night. Take back-to-back, mid-December games against Los Angeles and Boston. Bill resurrected from the dead versus L.A. He drove hard to the basket. He furiously elbowed for rebounds. He even intimidated Kareem on defense. “Tonight, Bill made even Jabbar alter his shots,” said coach Hubie Brown—slightly shocked.

Ah, but in the next night’s Celtics game in Boston, Cartwright played like a man in desperate need of smelling salts. Celtics center Robert Parish became another NBA “Sluggo” trying to decapitate “Mr. Bill.” Just once, I wanted to see Cartwright get angry enough to deliver an elbow to Parish’s sternum resulting in a scream that could’ve been heard back to New York. Not a chance.

“Cartwright loves to ‘finesse’ people,” says one NBA center. “He wants no part of the rough stuff. He’s happy to take his turnaround jumper, score his 18 points, and grab whatever rebounds come his way. He’s just not mean or hungry enough. The Knick players know it. Do you know why he’s not the captain? No balls.”

One last thing. Basketball is, for the most part, a simple game. Becoming a good team requires a fragile blend of talent, personality, coaching, and consistency. Especially consistency at the center spot. Without it, a team can never hope to play better than .500 basketball. Hence, the dilemma of the Knicks and the Nets.

When Moses Malone was named last season’s MVP, he said he’d rather not think of himself as the NBA’s most-talented player, but as one of its hardest working. “To me,” Malone said, “hard work is simply a matter of pride. Some guys may be great ballplayers, but there are times when they say, ‘I got it made. I don’t have to work tonight.’ I’m not like that. Even if I’m hurt, every night I try to give 110 percent.”

Now, if Cartwright and Dawkins had that kind of attitude, then perhaps I wouldn’t have to contradict my editor.