[What Earl Manigault was to New York’s playground basketball scene, Raymond Lewis was to Los Angeles’ hoops culture. Depending on whom you ask, Lewis was the greatest ever to lace ‘em in L.A. prep circles, the ultimate headcase, a victim of the system, and an all-time tragic figure. In an ideal world, Lewis would have retired roughly 40 years ago from the NBA as one the greatest guards of all-time. But off-court stuff got in the way and derailed his pro career before it got rolling. The mystery, which lives on to the present day, is what exactly derailed Lewis’ career?

What follows is a very good article that catches up with Lewis 16 years after the derailment. The article was filed by Richard O’Connor, who had a cup of coffee playing in the ABA before moving on to journalism. O’Connor was also featured in the blog’s last post (toward the bottom) with his blunt critique of Bill Cartwright and Darryl Dawkins that ran in the magazine New York Sports. Here, O’Connor is writing in the November 1989 issue of the magazine Philly Sport, and as all Lewis watchers know, the derailment of his career took place in Philadelphia.

A couple of quick comments. I just stumbled onto this 1972 quote from Bob Miller, Lewis’ college coach at Cal State LA coach: “Our freshman guard, Raymond Lewis, is the finest player—with the ball—I’ve ever seen.” The key words being, “with the ball.” Lewis was extremely ball-dominant. As O’Connor’s article hints, Lewis could melt down when the ball and the offense didn’t run through him. That also explains a lot. Lewis wasn’t about to share the ball with fellow first-rounder Doug Collins. In Lewis’ mind, he’d beaten out Collins in training camp. He deserved top billing and equal, or higher, pay.

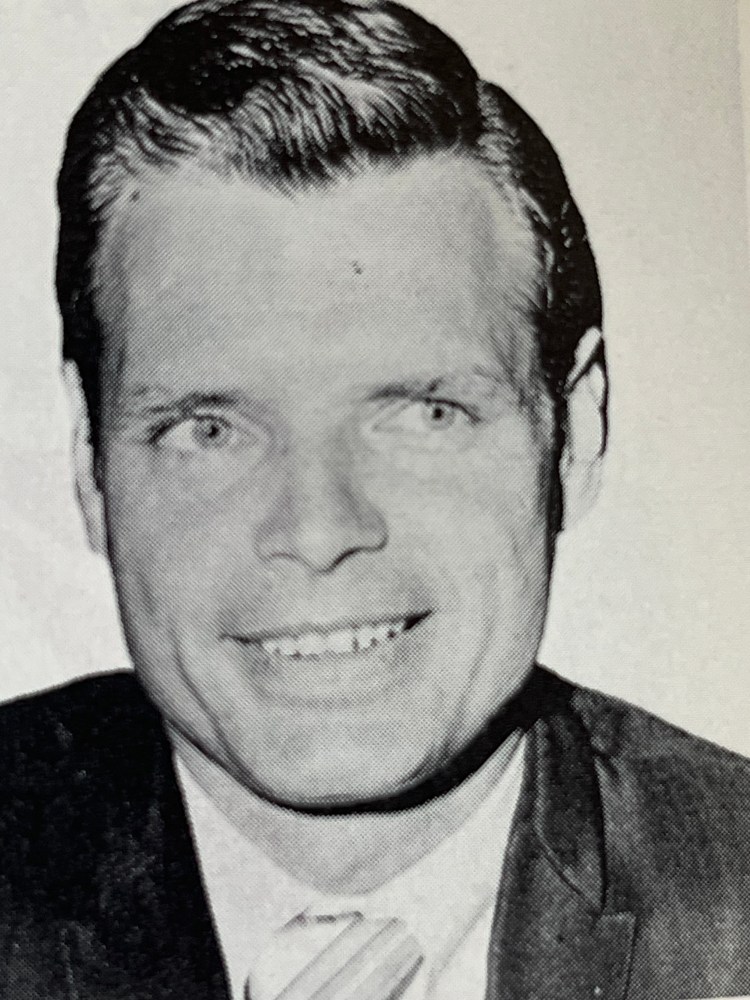

When you see the name Don DeJardin, pay close attention. DeJardin, the 76ers’ GM who signed Lewis, was a proud West Point grad and former basketball star. He got on well with those who shared his saluting, chain-of-command mindset. The buck stopped with him. DeJardin bridled at the 1960s counter-culture and its disruptive, down-with-the-man personalities. That included prominently Black players who were too 1960s hip to salute him or follow his orders. For DeJardin, a stingy, cost-cutting GM in Philly. Ripping up and rewriting Lewis’ rookie contract would have been a non-starter. I know all of this from researching Shake and Bake. Had Lewis not landed in DeJardin’s cold administrative hands, he might have had a hot time in Philadelphia during the 1973-74 season and beyond. Sixers’ coach Gene Shue, a former NBA All-Pro backcourtman, was very guard-friendly. Think Earl Monroe in Baltimore when Shue coached the Bullets.

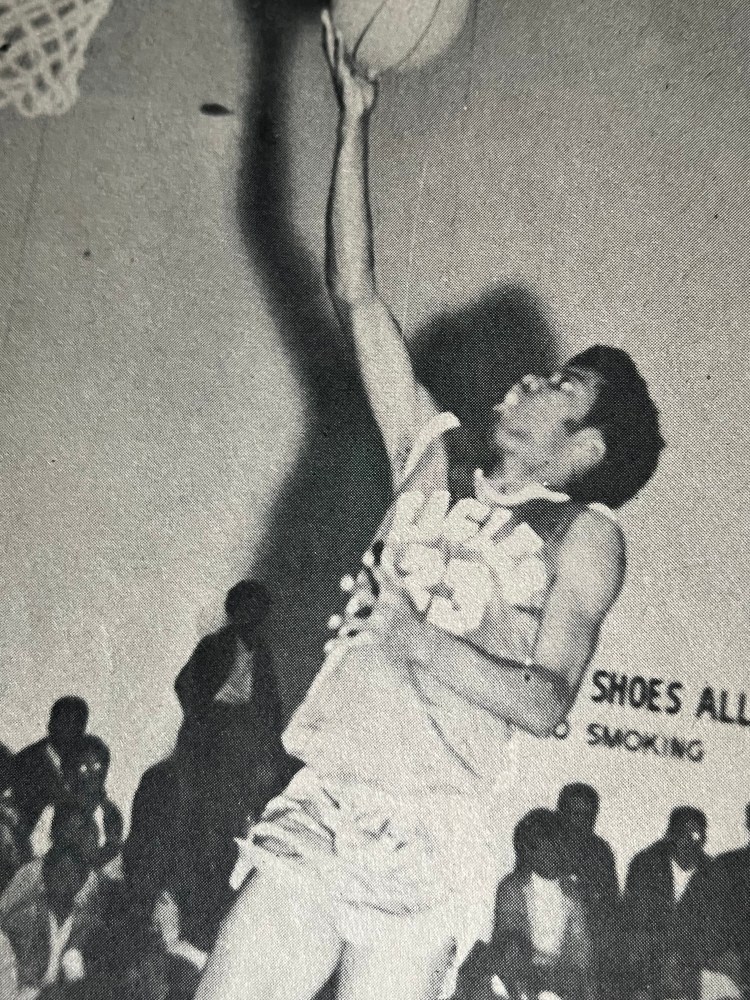

Was Lewis really that good? Yes. He could go jumper-for-jumper with the pros straight out of high school. For example, fresh out of high school in the summer of 1971, Lewis went head-to-head against ABA star and defensive force Mack Calvin. As this newspaper clip relates, Lewis didn’t blink. “They were playing ABA rules. Calvin was hand-checking me the entire game,” said Lewis of his first summer league confrontation with ABA star Mack Calvin. The Verbum Dei star was held to 34 points.”

Oh, and while I’m thinking of it, be sure to check out the recent Raymond Lewis documentary!]

****

Wasted talent in sports—especially in basketball—is an old and sad story. How good could Marvin Barnes have been had he not self-destructed? And Michael Ray Richardson could have rewritten the NBA record book—don’t you think?—if it hadn’t been for the nose candy.

Yet of all the NBA tragedies, the saddest, and certainly the strangest, is that of Raymond Lewis.

A 6-feet-1 guard out of Los Angeles, Lewis was a cult figure at Verbum Dei High School and a legend at California State-L.A., where his first season he beat out North Carolina State’s David Thompson to lead the country in scoring with a 38.9 average. As a sophomore, he averaged 32.9 points and was so dazzling, so unstoppable, that the wise men of the game sat around and predicted he would become the best college player in the country by his junior year.

But at the end of the sophomore year, Lewis decided to leave college, declaring himself eligible for the 1973 NBA draft under the hardship rule. The 76ers, after naming Doug Collins as the team’s (and the league’s) number-one pick, selected Lewis as the last player of the first round. Lewis was just 20 years old, making him, at that time, the youngest player ever to be drafted into the NBA.

Still, expectations ran high. Said New York Knicks scout Dick McGuire: “Raymond Lewis has more raw basketball talent than any college player in the country—and that includes Bill Walton. He might be the best draft choice Philly has made since Billy Cunningham.”

Lewis reported to the Sixers camp and bogarted everyone—including Collins. The Daily News bannered a headline: COLLINS TALKS A GOOD GAME, BUT RAYMOND LEWIS PLAYS IT. Another reported: LEWIS IS KIND OF YOUNG TO BE AN NBA LEGEND, BUT HE’S OFF TO A FAST START.

As it turned out, Raymond Lewis never became a legend in the NBA. Nor, for that matter, did he ever play in the NBA. Lewis ultimately walked away from pro basketball, disappearing one day into the mist, never to be heard from again. Over the years, ugly rumors about him periodically surfaced. He was a junkie, a pimp. There were even reports that he was dead.

****

I had always been curious about Raymond Lewis, and a year ago I decided to track him down. For the longest time, nobody seemed to know his whereabouts until, finally, a friend of a friend of a friend came up with a phone number. I called it. A man with a deep, gruff voice answered.

“Raymond Lewis, please,” I said.

“Yeah.”

I introduced myself and explained that I wanted to write a story about him. He was silent for a long time. Then he said, “I don’t know, man. There’s been a lot of strange things happened and said ‘bout me, so I don’t know if I want to be speaking to no writer.”

I pleaded my case.

“Okay,” he said, finally. “I’ll give you five minutes.”

“Where do you live?” I asked.

“Watts.”

Watts does not appear to have recovered from the bloody riots of 1965. Buildings on that neighborhoods Central Avenue are boarded up; stores are burnt-out; garbage clogs the gutters and mangy dogs roam the streets. Men and women of all ages, wearing shabby clothes and ski caps, slump in doorways.

On this warm evening, I am driving around Watts, trying to find Raymond Lewis’ house. I turn a corner and spot a group of teenagers. One is dribbling a basketball. I roll down the window.

“Excuse me,” I say. “Can you tell me where I’d find 110th Street?”

Eyeballs slide. Surly looks are exchanged. Nobody speaks.

“Ah . . . well . . . actually,” I manage, “I’m looking for Raymond Lewis.”

The one dribbling the ball brightens. “What do you want him for?” he asks.

I explain.

The kid says, “That man’s the best brother. He’s better than most of the dudes playing in the NBA.”

The chorus behind the kid grunts, “Yeah, baby, you tell him.”

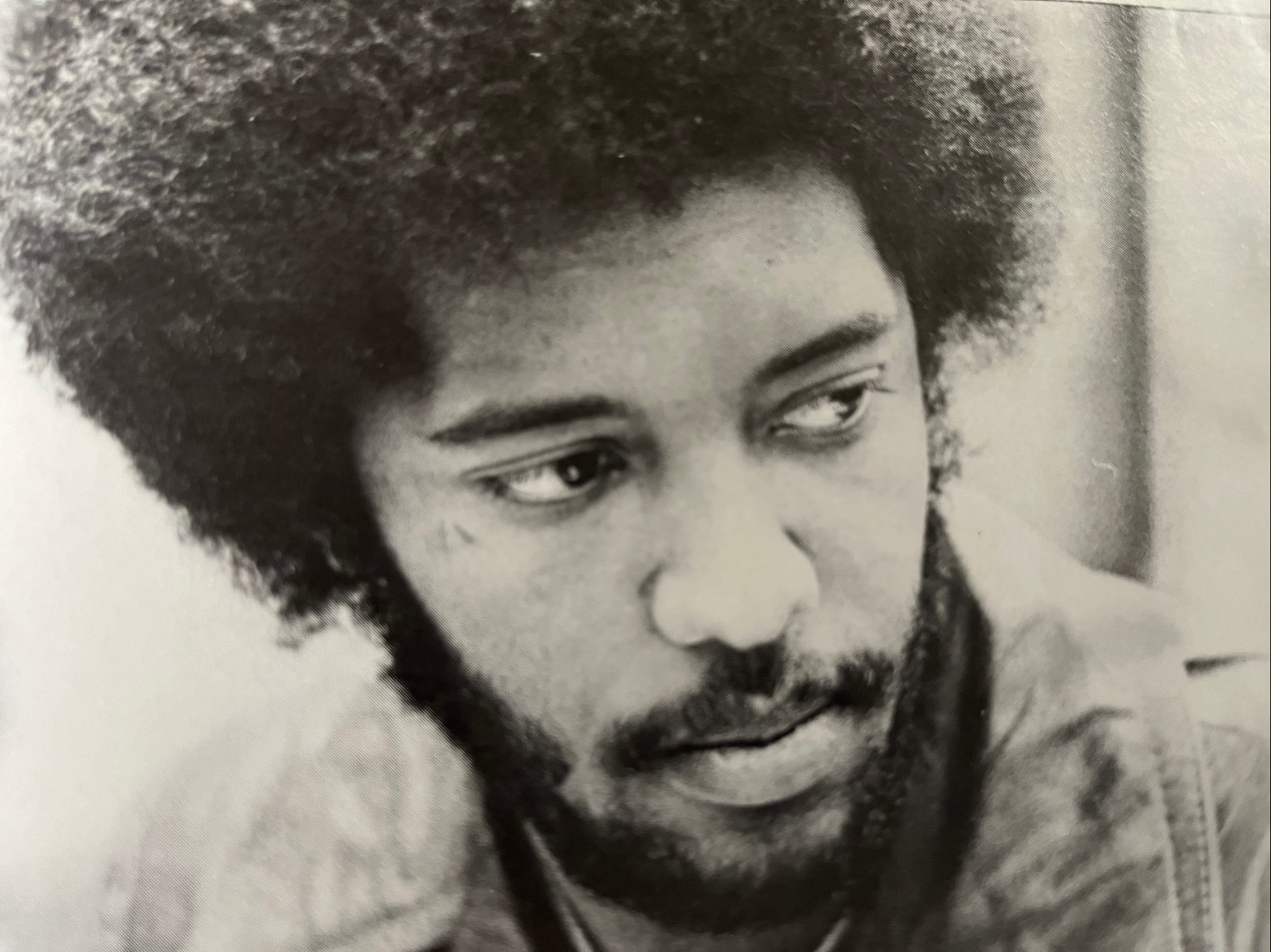

The kid gives me directions. I find the Lewis house. It is a tiny bungalow with a small dirt yard. Similar houses across the street are boarded up. Men are drinking beer outside the house when I arrive. They quickly scatter—except for one. He is a stocky man, around 6-feet-1, with a bloated face and drooping eyelids. He looks to be in his 50s. In fact, he is not yet 40.

He approaches me and says, “Did you find the place all right?”

I tell him about the kid and the kid’s comments. Raymond Lewis smiles triumphantly. “He’s right, you know. I’m a legend around here.” His smile quickly fades. He stares at me with piercing eyes. “As you can see,” he says, “I’m still alive.” He laughs crazily. “C’mon inside.”

We start to walk into his house, but Lewis stops and points to the building in the distance. “That’s where I went to high school,” he says. “Verbum Dei.”

The old-timers say that they never saw a basketball player at Verbum Dei the likes of the young Raymond Lewis. As a freshman, he was so good he simply awed people. He wowed them with speed and quickness. With deft passing and fancy dribbling. But, most of all, he mesmerized them with his most-lethal weapon—his jump shot. That was his gift, his art form. “He was gifted offensively,” says his former coach George McQuarn, “it was frightening.”

Indeed, his high school accomplishments, speak for themselves. Three times his team won the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) divisional title, and twice Lewis was named the division’s best player. “The bottom line on Lewis is that he’s absolutely the best player ever to come out of California,” McQuarn says.

Raymond Lewis’ exploits were chronicled more closely than perhaps any athlete in L.A.’s history. As a result, hundreds of college recruiters came to Watts and begged him to attend their school. When simple pleading didn’t work, they tried seducing him with cars, clothes, money, and women. Everyone thought he would go to Long Beach State, then coached by Jerry Tarkanian. But instead, Lewis chose California State.

Tark was crushed. “I never felt worse about losing a player,” he said.

Why did Lewis choose tiny California State? No one knows for certain, but in his freshman year, he drove a new Corvette; by his sophomore year, he had a new Caddy, a new Pantera, and a custom van.

Today, when asked how he could afford such luxury cars in college, he says, “Hey, I ain’t getting into that, man. You’re smart. You figure it out.”

While Lewis won’t discuss the school’s recruiting practices, he will willingly talk about his basketball career at California State and is happy to recall the times he scored 30 points. Fifty points. Seventy points. And don’t forget the game against Long Beach when he got 53 big ones and led his team to a double-overtime victory. Word had it that Tark was so upset, he nearly swallowed his “biting towel.”

“I played against Raymond Lewis in his first game as a sophomore,” remembers Ray Vyzas, a former All-American at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut. “I couldn’t believe how quick he was. And his shot? Oh, man, could he stick it. From all over the court.” Vyzas shakes his head in amazement. “Let me tell you. Raymond Lewis would have won with Mo, Larry, Curly, and Shemp as his teammates.”

****

We enter the Lewis house now. It is small. Faded and torn yellow curtains cover the doors and windows. The room smells of cat urine. The only furnishings are a couch, chair, a tape deck, speakers, and a pile of albums.

When we both sit down, Lewis says, “Okay, what is it that you want to know?”

For starters, I say, I’d like to know what he’s been doing the last few years. He hems and haws. Mentions a variety of menial jobs. Clerk, messenger, handyman for his grandfather, who owns the house he lives in and others in the vicinity.

“Who employs you now?” I ask.

“Nobody,” he says. “Right now, I’m looking.”

Suddenly, his face contorts into a scowl. He says, in an angry voice, “Look, man, I know why you’re here. You want to know if Raymond Lewis is strung out like people say. Well, he ain’t. I’m alive and well.”

His voice drops, becomes confused. “All I am is a living example of someone who’s been screwed by the NBA. I mean, I was blackballed by them suckers. They knew I could play. They just didn’t want to pay me what I was worth.”

His hands knot into fists. Tendons bulge in his neck. His eyes are wild. “Look, man,” he shouts, “when I look back at what happened to my pro career, all I can say is, it was a nightmare.”

****

Sixteen years later, the nightmare is still difficult to figure out. But here are the facts. Lewis says the Sixers promised him a $1 million-a-year contract to go hardship. Don DeJardin, then general manager of the Sixers, claims, “That’s simply not true.” Whatever the case, Lewis, who foolishly acted as his own agent, signed what he thought was a three-year guaranteed contract for $450,000. Truth was, the contract was for $190,000—a $25,000 signing bonus, $50,000 the first year, $55,000 the second, and $60,000 the third. The remaining money was deferred.

“Raymond signed what was at the time a contract commensurate with other players drafted before and after him that year,” says DeJardin, now a California businessman. “In fact, he received a fairly substantial bonus for the time.”

Be that as it may, a Philadelphia reporter told Sports Illustrated that the contract was appropriate for “a third-round pick with terminal case of acne.” Angered, Lewis nevertheless reported to camp and so totally embarrassed Doug Collins that SI reported that 76ers’ coach Gene Shue “refused to allow Collins to guard Lewis, and that is when Lewis decided he needed some new and richer fine print in his contract.”

When Lewis didn’t get it, he walked out of camp one day and flew home. He now says Shue called him and promised to renegotiate his contract if he would come back. Yet, when Lewis got back to Philly, he claims Shue reneged on the deal. DeJardin, however, emphatically refutes that claim: “No way did we ever promise to renegotiate Raymond’s contract. Look, he did play very well in preseason. But why would we have made any promises when he hadn’t even played in a regular-season game?”

Whatever, Lewis once again walked out on the team, this time at halftime of an exhibition game. Shue sent assistant Jack McMahon to bring him back. “The thing with Lewis was,” Jack McMahon told me just before his death last spring, “he really felt that since he was outplaying Doug, he should have gotten more money.

“But I told him to be patient. For one thing, he had incentive clauses in his contract, whereby he could have made more money. But Raymond wouldn’t listen. He was obsessed. But his contract was already signed.”

McMahon paused a second. “Let me say this about Raymond Lewis. The kid could really play. I mean, he could have been a star in the NBA. But he was always playing head games with others and himself.”

Lewis sat out that first year. The following season, he came back to Philly, but walked out again. Same reasons. He signed with the Utah Stars of the old American Basketball Association, but because he was still under contract to the Sixers, he was pulled off the Stars’ bench right in the middle of a game.

In 1975, new Sixers’ GM Pat Williams decided to give “the Phantom,” as he was now called, another chance. “When I was GM with the Bulls in 1973, I went to see Lewis play against Northern Illinois,” remembers Williams, now with the Orlando Magic. “When I left the gym that night, my body was tingling. I mean, here was a kid who had something special. Real star potential. So, when I took the job with the Sixers, of course I wanted him.”

The Sixers signed Lewis and sent him to the Los Angeles Pro League. Lewis played well, but once, when he came down on a fastbreak and didn’t get the ball, he continued running out the gym.

He reappeared a few months later at Philadelphia International Airport, where he debarked the plane with Miss USA on one arm and a Bible in the hand of the other. At a press conference the next day, Lewis announced, “I’m ready to forget the past and just play basketball. I’d say it’s about time to start my career.”

But he didn’t play well in camp. He blamed it on injuries. Others blamed it on the fact that rookie Lloyd Free upstaged him. Regardless, Lewis, as players like to say, “copped an attitude.” He sulked, got lazy, and then one morning, as Pat Williams was walking into practice, Lewis was walking out. “I can’t take it anymore,” he said. “I’m going home.”

“The truth is,” says Williams, “Raymond was mentally tough enough to play in the league. He lacked inner strength.”

Over the next few seasons, Lewis would have tryouts with the New York Knicks and the San Diego Clippers. But neither worked out. By then, his moves were slower, his jumper erratic, and his once-burning desire for greatness was reduced to a mere pilot light.

****

Back in his living room, Lewis shifts in his chair and says, “I still don’t know who the Sixers thought they were kidding. I would never have left school unless I thought I was going to get the millions, not a lousy few grand. It was bad enough they lied to me, but once I started cleaning Collins’ clock, they should have reworked my deal. But, of course, Collins was the golden boy, while I was this uppity Black kid.”

Lewis goes on to say that his problems with the Sixers had racial overtones, and that he was discriminated against. Yet, even as he says this, his voice lacks conviction. “I’m just a victim of racism,” he says softly.

As Lewis is speaking, a tall, pretty young girl bursts into the room. It’s his daughter, Kamila, who is 13. She excitedly begins to ask her father a question.

“Wait a second,” Lewis scolds, “can’t you see I’m talking to someone? Now, excuse yourself to my guest.”

Kamila looks down at her shoetops. “Excuse me,” she says sheepishly.

Raymond Lewis smiles. “That’s good,” he tells her. “Now, what is it that’s so important that it can’t wait.”

He puts his arm around his daughter’s waist; she tells him about wanting to go to see her grandmother. Watching Lewis and his daughter, I am reminded of something he told me earlier when he said, “My family means everything to me.”

Indeed, he is—and always has been—extremely close to his grandparents. Even though his own mother and father are divorced, they both live nearby, and he sees them regularly. As for himself, he’s been married to the same woman, Sandra, for 16 years. Aside from Kamilla, they also have a son, Rashad, who is nine.

Lewis and his daughter finish their conversation. He kisses her cheek. She leaves. For a moment, Lewis’ eyes mist over. He sags in his seat. And just as I think he’s going to get melancholy, he shoots upright in his chair. “What are you paying me for the story?”

Stunned, I said magazines don’t pay subjects for interviews. “Well, in that case,” he says, angrily, “you gotta go. No offense, man, ‘cause I like you. But I just don’t see why I should tell you my life story for nothing. I mean, it’s unfair. Here your magazine’s gonna use me to sell magazines, and I don’t get a penny of it.” His eyes widen, his voice rises. “Bullshit!”

He falls silent. Takes a minute to compose himself. Then in a soft voice, he tells me how an actor he knows wants to do a movie about his life. He adds that if that doesn’t work out, maybe he’ll see about getting a tryout—with the Lakers.

“Absolutely,” he says. “Just ask anybody in the neighborhood. I can still do it.”

He stands. I stand. We walk out of the bungalow into the fading daylight.

“Don’t mean to throw you out,” Lewis says. “But I ain’t gonna be used by anyone so they can make money off me.”

As I look at Raymond Lewis, I can’t help but feel sad for him. He could have been one of the best, if not thebest, basketball player ever to come out of L.A. Yet, unlike some ex-athletes, he has not descended into drugs and despair. Even though Lewis lacks direction in his life, he still has a family who loves him. For that he should consider himself a lucky man. He shakes my hand goodbye. And then he turns, the legend that never was, heading toward his bungalow in pursuit of the rest of his life.

Doug Collins declined to do an interview for the documentary and has NEVER spoken about Raymond.That is some sucka ISH.Somoone needs to ask him about Raymond!

LikeLike