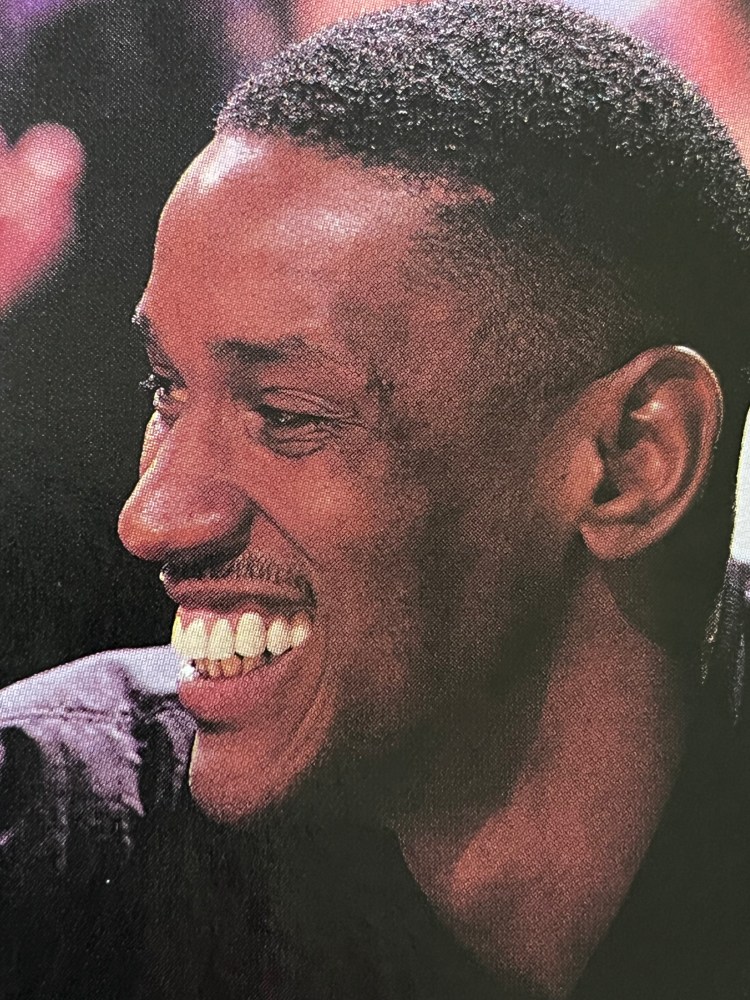

[The other day, I started flipping through the April 1995 issue of the magazine Rip City in pursuit of something or other. Along the way, I noticed an article about Otis Thorpe, the now-former NBA great. I’m a sucker for a good lead, and this one reeled me in fast for this nicely done profile of Thorpe, a rock-solid performer with Kansas City/Sacramento, Houston, briefly Portland, and then a scattershot of other NBA teams until his retirement in 2001. But what really caught my eye was the byline: Fran Blinebury. He’s now one of my favorites, and I pass along this rare Blinebury gem about this polished NBA power forward, one of the best from the 1980s and 1990s.]

****

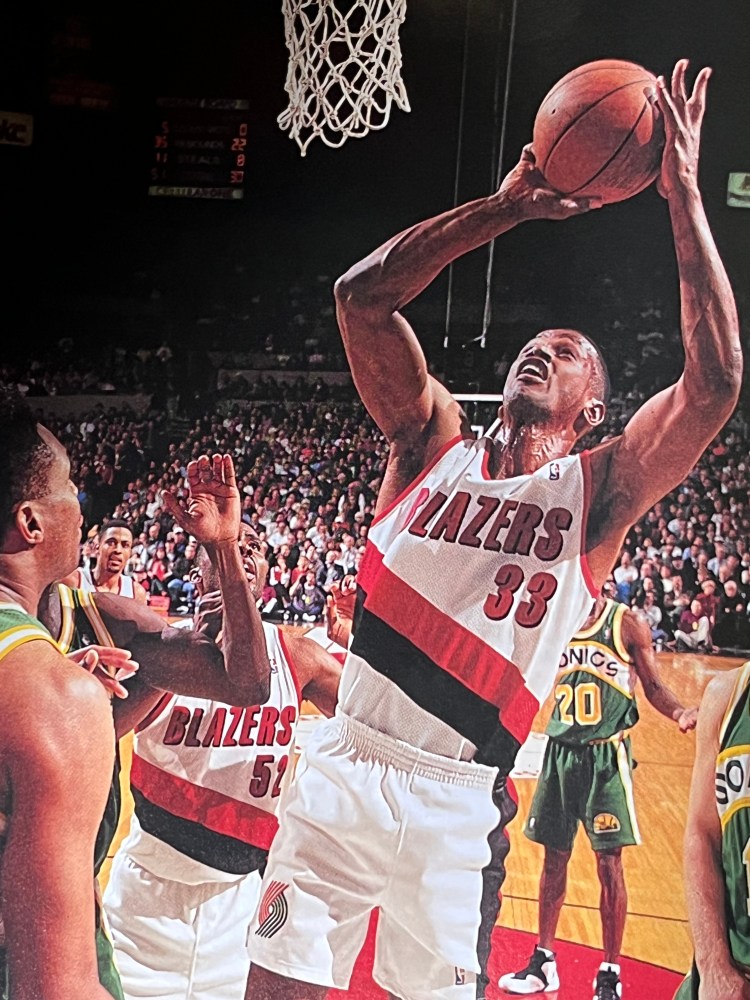

There are players who can fly through the air with much greater ease and those who light up arenas with better-looking jump shots. But few in the NBA today show up, quite literally, like Otis Thorpe. Throughout his 11-year career, the Portland Trail Blazers’ new power forward has been basketball’s version of the sun rising in the east, of the tides washing in, of broken political promises. In other words, he’s a constant in a world that changes with every tick off the clock.

When you attend any pro basketball game, you expect to see a certain number of flamboyant plays and great shots. But when you come to see Thorpe play, you also can count on a man who is dedicated to doing his job, night in and night out, game after game, in city after city. At one point in his career, between January 1986 and November 1992, Thorpe played in 542 consecutive games.

That means Thorpe always is there with his sneakers laced up, his game face in place. Whether it was while trying to carve out some kind of reputation in his early days with the Sacramento Kings or playing a key role in the Houston Rockets’ championship 1993-94 season, Thorpe approached his profession the same way: as a professional.

That will not change now that he’s part of the Blazers front line. He lives with the bumps and the bruises and the aches and the pains and moves forward relentlessly. His is a style that is classical and enduring. Against the backdrop of youngsters who speed onto the scene with the flash and roar of a fuel-injected dragster, Thorpe is the dependable pick-up truck that keeps piling up the miles on the odometer and hardly ever seems to need a tune-up.

“I’d say that if you were another athlete, he’d be the ultimate teammate because his only real concern is the common goal,” says Jim Carlton, Thorpe’s former coach at Lake Worth High School in Florida. “But don’t even bother trying to crawl inside his head, because he’s only going to let you know what he wants you to know.”

So, more than a decade after he was the ninth overall pick in the draft by the then Kansas City Kings, what do we know about Otis Thorpe? We know that he’s a chiseled, 6-feet-10, 246 pounds but are surprised to discover that he never had to lift a single weight to get that way. We know that during Thorpe’s stay in Houston, he was always in the role of second banana behind Hakeem Olajuwon and simply went about his job and made the most of it, even at a cost of individual accolades and lucrative endorsement dollars. We know that offensively his game is limited mainly to the area within 10 to 12 feet of the basket. Yet, rather than be stifled, Thorpe has made the most of that small domain, consistently perching himself among the league leaders in field-goal percentage. No wasted motion.

During Houston’s drive to the title, in four consecutive playoff series, Thorpe engaged in one-on-one matchups against four of the NBA’s best power forwards (Buck Williams, Charles Barkley, Karl Malone, and Charles Oakley), yet never was overwhelmed.

“You don’t think about it being one after another or that you’d like an easy matchup or a night off,” Thorpe says. “It was a challenge for me. Buck is the kind of player that I’ve always respected for his professional demeanor. I spent my career trying to duplicate him. Barkley brings something completely different to the table. He’s a unique talent. Malone is like Barkley because he’s so talented. And Oakley is a worker like Buck.

“You look back when it’s all over, and there is a sense of accomplishment. But it doesn’t come from my being able to outscore anybody or outplay anybody in a game or a series. The accomplishment is in having finally won the championship. That says the only thing that I care that anybody on the outside knows about me—I was willing to make the commitment to win it all.”

****

Otis Thorpe grew up in Boynton Beach, Florida, in a situation that was far from ideal, but was all Thorpe ever knew until he went to college. The third youngest of nine boys and three girls, his father left home soon after Thorpe became a teenager. He was raised by his mother, who died in her 40s, and then by his aunt.

Thorpe, despite an already large stature, never bothered to join the basketball team at school until he was a junior in high school. All of his playing up to that point was only in street games like “21.”

“I didn’t look at basketball in terms of the bigger picture of life,” he says. “I didn’t watch the game on TV.” In fact, the first game Thorpe ever watched from start to finish was the 1979 NCAA championship, where Magic Johnson out dueled Larry Bird.

“I never thought about someday playing against them. I didn’t think that far ahead in terms of basketball. All I cared about was that when I had 19 points, I just wanted to get to 21.”

His road to the NBA began when a classmate at Lake Worth High finally convinced Thorpe to try out for the team. Coach Carlton initially put Thorpe on the junior varsity squad, but only to help the already. 6-feet-9 young man adjust to the structure of organized basketball. “You only had to look at him to know that he was going to be able to do pretty much whatever he wanted,” says Carlton.

Thorpe then played [center] for Providence College, and when he left in 1984, he was the Big East Conference career leader in rebounds and ranked second behind only St. John’s Chris Mullin in scoring. But more than those numbers and the fact that pro scouts now were watching, this shy kid who had trouble looking interviewers in the eye when he arrived on campus had blossomed into a confident man with a degree in social studies.

At the Aloha Classic, a pre-draft NBA college all-star event, Thorpe played so well that many observers felt he was slighted when he wasn’t named MVP. “It went to somebody else because of reputation and image,” Thorpe says. “That taught me about things, but that experience also gave me the confidence that, with my game, I could play with anybody out there.”

By the time he’d played four seasons with the Kings, who had since moved to Sacramento, Thorpe was a 20 points-a-night scorer who appeared on the verge of becoming a perennial NBA all-star. Instead, a 1988 trade sent Thorpe to the Rockets and designated him to become a member of a supporting cast—albeit with an important role—behind Olajuwon.

In Houston, Thorpe was named to the 1992 All-Star team. Still, even the brush with individual notoriety turned sour. Thorpe play just four minutes—by far the fewest of any all-star—never getting off the bench in the second half of what became Magic Johnson’s retirement celebration and an easy 153-113 Western Conference win. The bitter feelings toward West coach Don Nelson remain.

“I was highly upset,” Thorpe admits. “You had a guy [Nelson] who played me just a few minutes in the first half and made a point of telling me at halftime that he was sorry and was going to make it up to me. I sat right next to him through the whole second half. He never looked at me. He never said anything to me.”

Thorpe says he now classifies the All-Star game as “another learning experience.” He admits that he’s always interested in the decisions made by the coaches. “I love the strategy. I like to get involved. But I’ll admit, sometimes I get too involved. I’ll say too much at the wrong time. It bothers people. But I do my job.”

Thorpe is a big man who can run the floor like a greyhound and finish off the fastbreak with the kind of thunderbolt slam dunks that leave the backboard shaking. He has exceptional low-post moves, and he can be practically unstoppable on the old tried-and-true pick-and-roll play. Thorpe once got on such a roll with the classic two-on-two play that former Houston coach Don Chaney stood in the middle of a huddle during a timeout and announced: “We’re just going to keep running that play to Otis until they figure out a way to stop it.” They never did.

You watch him on the court, and it can be like watching a machine. He doesn’t do everything. He never tries to do everything. But what Thorpe does, he does well. Filling the lanes on the break. Shooting the baby hook close to the basket. Rebounding and playing defense. No wasted motion.

At 32, he is more vulnerable to the nicks and bruises of the NBA grind. But what bothers him more are some of the changes he’s seen take place in the game.

“I’m not ancient,” Thorpe says, “but I feel removed. I feel older than a lot of today’s players when I see young guys running off at the mouth for no reason, using all kinds of different language. They’ll stare you down, they’ll talk at you, stuff like that. I don’t like it. All that stuff separates what we’re about from the way the game was meant to be played.

“Talking has always been a part of the game. ‘You can’t guard me.’ Little wisecracks. That’s all fun. [Larry] Bird was great at it. But dunking and then standing over somebody and pointing at him? I don’t get it.

“The era when we came into the league, you felt like you had to prove yourself on the court. Now, they come out talking. They think it’s entertainment, that it’s about manhood. But really, that’s ridiculous.”

Winning the 1993-94 NBA championship was the crowning moment of an MVP season for Olajuwon. For other Rockets, it raised them far above their prior individual reputations. For Thorpe, it validated his work ethic, his sense of team.

“It marks my career, maybe defines it,” Thorpe says. “People will always be able to look at what I did, look beyond the numbers and say, ‘Whatever else, he contributed, played a role in a championship.’ That’s all I’ve ever wanted.”

Thorpe stayed up most of the title-clinching night celebrating with a couple of college friends, who had traveled to Houston and New York to watch all of the NBA Finals. After an hour or two of sleep, he was up and out on the golf course, where he played nine holes.

“I don’t know why I did it,” he says. “I don’t ever play just nine holes. I guess I just wanted to be there, outside, away from the crowds. I needed some time by myself. To relax. To reflect. Maybe to think about what it took to get there, and what it would take to do it again.”

For Otis Thorpe, that’s par for the course.