[NBA coaches often talk about how critical it is for young players to find the right team with the right fit for their talents. It’s so true today, and it’s been so true since the days of Joe Fulks, Bill Russell . . . and, well, Danny Vranes.

Vranes, heading into the 1981 NBA Draft, was considered a top small forward prospect based on his stellar four-year career at the University of Utah. The scouting report on Vranes was straightforward: “exceptional shooter [though with limited range] . . . “exceptional quickness, good leaping ability, but needs work on defense and ballhandling.”

What follows is five brief newspaper articles tracking Vranes, his fit, and the arc of an NBA career that would never live up to its top-prospect billing. Vranes’ story isn’t unique by any means. But his story is interesting just the same. Time would tell that he wasn’t an exceptional shooter at all, and defense, not offense, would be his NBA calling card.

Usually, I don’t run wire stories. They’re not that hard to find. But this Associated Press story, which was filed on June 10, 1981, sums up nicely Vranes’ entry into the league as the fifth pick in the 1981 draft.]

****

Seattle SuperSonics’ coach Lenny Wilkens went to sleep Monday night with visions of small forward Al Wood of North Carolina dancing in his head. He woke up Tuesday morning and found out he’d have to settle for 6-feet-7 small forward Danny Vranes of Utah instead.

“When I went to bed,” Wilkens said, “I thought Al Wood would be there for us. When I got out of bed, I knew that wasn’t going to be the case.”

In a trade of first-round draft choices late Monday night, a trade Wilkins didn’t know about before he retired for the evening, the Atlanta Hawks swapped places with the Chicago Bulls. That put the Sonics, drafting fifth overall, behind the Hawks in the picking instead of in front of them.

According to the Sonics’ strategy before the trade, Wood would be available to them, because the Bulls had something else in mind. “There had been some talk about a trade between Atlanta and Chicago,” Wilkens said, “but I thought it was dead. But after I heard, the trade had been made, I knew Al Wood wouldn’t be available for us. I didn’t need to call Atlanta, either. I knew for sure they would pick him.”

Before Tuesday’s draft, the names of Wood, Vranes, and 6-9 forward Orlando Woolridge of Notre Dame were tossed about by the Sonics as possible first-round draft picks. Woolridge is considered more of a power forward.

So, after Wood was chosen, that left Wilkens to decide between Vranes and Woolridge. “I felt,” explained Wilkens, “our need was more for a true small forward.”

Following Seattle’s selection of Vranes, Woolridge was taken by Chicago. ”I think this was an important draft for us,” said Wilkens. “We definitely got a good player in Danny Vranes.”

Vranes was a second-team All-America selection and a three-time first team Western Athletic Conference pick—as a sophomore, junior, and senior. The 210-pounder, a native of Salt Lake City, averaged 15.3 points in his four-year Utah career, including 17.5 as a senior [playing with Tom Chambers].

[Vranes was penciled in to replace Seattle’s aging John Johnson at small forward. But the Sonics were in transition, and Vranes’ game got lost in all the shuffling of players, gameplans, and the pressure on Lenny Wilkens to win immediately. The former All-American wasn’t featured on offense, poking a hole in his confidence. Matter of fact, Vranes found himself mostly anchored to the bench and fending off whispers that the Sonics should have never drafted him so high. Here’s a telling snapshot of Vranes’ uneven rookie campaign from Chuck Stark with the Kitsap (WA) Sun. His story ran on March 3, 1982]

Danny Vranes came out of the fog Wednesday night to play his best professional basketball game. The 6-7 rookie, the fifth player picked in the entire college draft, scored 13 of his pro-high 15 points in the fourth quarter of Seattle’s 136-107 romp over the Cleveland Cavaliers.

The performance couldn’t have come at a better time. Vranes, it rhymes with brains, was turning into something of a headcase as he watched his playing time fluctuate from game to game. Until Wally Walker’s injury, Vranes, fellow rookie Ray Tolbert, and third-year pro Greg Kelser were sharing the equivalent of about one quarter’s worth of playing time.

Vranes did not play against Boston or Los Angeles, but started at Utah in place of Walker and played 20 minutes. Then, on Sunday, Kelser started, and Vranes played three minutes.

“The biggest adjustment for me has been this thing of being in a fog over what my role is,” Vranes said following Sunday’s loss to Phoenix. “The other night in Utah (last Friday), I had no idea he (Lenny Wilkens) wanted me to start until just before the game, and then today, I had no idea I’d sit out so much. As far as the playing time goes, I just don’t know what’s happening. It’s frustrating. Ask Lenny what’s going on.”

Wilkens tackled the question following the win over Cleveland. He didn’t exactly sympathize with his promising rookie forward.

“When you’re a professional athlete whether it’s one minute, two minutes, 10 minutes, or 15, you’re supposed to be ready for every game,” said the Sonic coach. “If I play you seven minutes, and you’re as big as [Vranes] is—6-7, 210 [pounds]—and own a 40-inch vertical jump, and you get me one rebound every time I play you for seven minutes, what makes you think I’m going to come back at you?

“I mean, there’s no excuse for that. I don’t care what kind of fog you’re in. He has a lot of talent, and I’m going to give him an opportunity if he wants it,” continued Wilkens.

“You see, he’s got to show to me that he wants it. The other day in practice was the best practice he’s had in a long time, and I thought he worked real hard in the game tonight. He acted like he wanted it.

“I’m glad to see him play as aggressively as he did. I think he’s very capable. We’ve always been high on him, and I don’t think he’s played as well as we felt he could play.”

Vranes said he was comfortable on the court for the first time in a long while, and his play reflected it. His outside shot has been a question, but he banged down a pair of 16-footers against the Cavs. “I felt good about myself out there,” said Vranes. “I was relaxed and confident.”

[Vranes stayed ready and moved into the Sonics’ starting lineup for most of his sophomore season. But his numbers remained subpar, especially for a former high draft pick. Vranes averaged 6.9 points and 5.2 rebounds in just 26 minutes per game. “Has a basic flaw—he can’t shoot at all,” wrote one critic, though, to be fair, Vranes did shoot 52 percent from the field in year two. His range, however, was clearly limited.

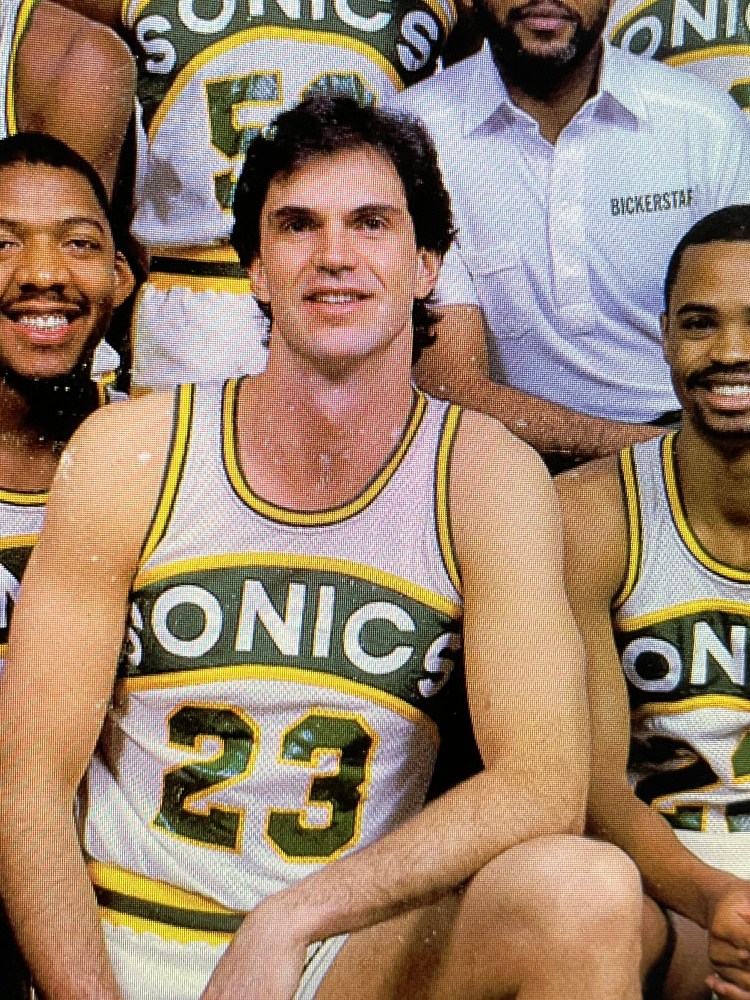

Though now starting, Vranes’ fit in the lineup was never ideal. On a Sonics’ team with several established scorers in Jack Sikma Gus Williams, Fred Brown, David Thompson, and others, Vranes accepted a totally new role as the scrapper, the guy who fought for loose balls, threw an occasional elbow, and locked down on defense. “ As one of Vranes’ critics opined: “Hustle will only carry him so far in this league.” But as John Blanchette, a columnist for Spokane Spokesman-Review noted before Vranes’ third season, the Sonics still stood by their man, even if he wasn’t featured in any way. Blanchette’s column ran on September 28, 1983]

Something tells you the Seattle SuperSonics really want Danny Vranes to make it. Young players, with better numbers have been phased out by the Sonics before. In fact, being a high draft pick with Seattle is generally a good signal to check out the real estate listings [elsewhere].

Only three of Seattle’s No. 1 draft picks—Fred Brown, Tom Burleson, and Jack Sikma—have ever lasted three full seasons with the team, and Burleson was traded immediately thereafter. So, here is Daniel LaDrew Vranes . . . on the threshold of season No. 3 in the National Basketball Association.

And he’s quite aware that nothing he’s done in his first two seasons—his career scoring average is 5.9—has moved the Sports Illustrated people to have a 2 x 3 color poster [of Vranes] in the works for the Christmas rush. “I’m not where I thought I’d be two years ago,” he confessed Tuesday during a visit to Spokane.

“But I feel like I’ve improved every year. Everybody has higher goals and aspirations about what they can do. Maybe I underestimated a little bit the talent of the players in the league. Maybe at first, I was a little in awe. It’s been trial and error, but I’m comfortable with how my game has come along.”

And so, too, are the Sonics.

Comfortable enough to have traded Wally Walker a year ago, to have cut the cord with John Johnson, and to have shipped Greg Kelser to San Diego last month. That list pretty much covers Seattle’s starters at small forward for the last six years.

“They must feel I’m the right man for the position,” Vranes acknowledged. “I know I do.”

There is no little irony, then, in noting that one of the principles in that August trade with San Diego, was Al Wood, who joined the Sonics along with Tom Chambers. When Seattle made Vranes its No. 1 draft pick in 1981, Coach Lenny Wilkens actually wanted Wood—and figured to get him until Atlanta and Chicago exchanged first-round numbers.

Wood is now with his third NBA team, and Danny Vranes is comfortable. Indeed, rather than fretting over Wood’s arrival, Vranes is excited about the prospect of being reunited with Chambers, teammates for four seasons at the University of Utah.

[Vranes upped his scoring average to 8.4 in his third season, though the boobirds continued to snipe, “Move him three feet from the hoop, and his offense is nonexistent.” But, as this March 29, 1984 story from the Salt Lake City Tribune’s excellent Lex Hemphill points out, the critic should have been watching the other end of the floor. Vranes was now recognized around the league as a defensive specialist, and a pretty good one at that.]

Danny Vranes hardly gets a chance to catch his breath these days. For instance, Wednesday night in Seattle, his assignment for the Seattle SuperSonics was to guard Kansas City’s Eddie Johnson, the league’s 16th best scorer. Then he gets on a plane for his only trip this season to Salt Lake City, and when he looks up at the Salt Palace Thursday night, he’ll be guarding the Jazz’s Adrian Dantley, the league’s No. 1 scorer.

Then, it’s on to San Antonio to guard the league’s No. 9 scorer, Mike Mitchell, and after that it’s Denver and the No. 6 scorer, Alex English, and, well, as Vranes sighed earlier this week, “It one right after another . . . just go down the list.”

You go down the list of small forwards in the NBA, and you’re looking at the position that is most loaded with scoring punch in this league. Except, that is, in Seattle, where Danny Vranes resides.

Vranes, who was No. 5 on the University of Utah’s all-time points list, is a mere No. 5 on the SuperSonics’ 1983-84 points list. He averages only 8.6 points a game, as the Sonics rely less on their small forward for scoring than does any other team in the league. And it is that fact that makes Vranes’ job as a defensive specialist one of the most thankless in the NBA.

You see, Vranes doesn’t have the luxury of matching the other guy in points, like, say Dantley and Mark Aguirre throwing 30 points at each other. Danny’s not going to score 30. In fact, he’s probably not going to score 20—he’s done it only once this season. His job is simply to try and stop the other guy.

And he never gets to duck. Some teams will occasionally try to put their power forward on the other team’s high-scoring small forward, but the 6-feet-8 Vranes gets all the tough assignments. Or, as he says, “You definitely don’t have a night off.”

Put it this way. Of the other 22 forwards in the league against whom Vranes defends at the start of every Sonics game, 11 of them—fully half—are in the league’s top 20 in scoring. Breaking it down some more, 11thof the 22 lead their team in scoring, and eight others are second on their team in scoring. Vranes’ mission in his 27 or so minutes per game is to stop them.

There are the established small forwards like Dantley, Aguirre, English, Mitchell, Johnson, Jamaal Wilkes, Purvis Short, Calvin Natt—and, hey, we haven’t even gotten out of the West yet. Some teams play two power-type forwards, and in those cases, Vranes ends up guarding the better scorer—Terry Cummings, Larry Nance, Cliff Robinson, Clark Kellogg, etc. No nights off.

Thankless? You bet. For instance, when the Jazz routed the Sonics last Sunday in Tacoma, Dantley romped for 40 points, many of them coming at guard and many of them coming when Vranes was cooling on the bench with foul trouble. But all the box score says is that Utah’s small forward got 40 points, Seattle’s got two. That’s the kind of recognition Vranes can count on. “I feel the Sonics expect me to concentrate on the defensive end more than anything,” explained Vranes.

And just how well does Vranes do in stopping the big scorers? Well, one witness for Vranes’ defense is Jim Marsh, who coached Danny at Utah and who has watched all his Sonic games the last three years as the color man on the Sonics’ cable channel.

“He’s the best defensive forward in the Western Conference,” says Marsh. “And I didn’t say small forward. I said the best defensive forward in the Western Conference. I firmly believe that.”

What makes him so effective? “There are two areas that he’s very good at,” said Marsh. “One, he’s very good away from the basketball. He is aware of the basketball at all times. He covers his man when he doesn’t have the ball, and not many players do that. Secondly, he’s tough to score on, one-on-one. He’s a good ball defender. “

“He’s a role player, and I think he does it well,” credited Jazz coach Frank Layden. “He’s a good defender. He plays hard. He puts his body against people. He’s a rough player. I like him. He plays hard, and that’s something you always have to credit.”

[Vranes continued in Seattle for two more seasons, mostly coming off the bench again as a defensive stopper. Hustle had indeed taken Vranes so far in the NBA, and at age 27, his NBA future looked established as a reliable, team-first reserve for 10 -15 minutes a night. Vranes still fielded questions about him being a first-round bust. “Sure, everybody wants to be in the limelight, and everybody wants to get the recognition,” he deflected. “I would like the attention if it were there, but I’m definitely not displeased or unhappy. I’m just grateful that I’m still in the league.”

Then, before the 1986-87 campaign, the Sonics traded Vranes to Philadelphia. He spent the next two seasons backing up the young Charles Barkley. Vranes did his job, got along with his new teammates (he was their union rep), and stayed ready. They nicknamed him, “The Sprinkler,” probably for pouring cold water on hot scorers. Philadelphia News’ great Phil Jasner filed this brief piece about Vranes on January 21, 1988. Jasner summed up nicely the state of Vranes’ pro career, nearly seven full seasons after the 1981 NBA Draft.]

Danny Vranes played 30 minutes last night. He hadn’t played 30 minutes in the 76ers’ last six games, hadn’t played at all in two of them.

Vranes is good about those things. He accepts his role, offers what he can, whenever he is asked. Coach Matt Guokas had to ask in a hurry last night, because [Philadelphia’s] Cliff Robinson left with a lower back strain after the first 1:47. Vranes had four points and two rebounds, blocked five shots, battled for position.

“A lot of guys can’t handle the situation when they have to come off the bench, when they don’t play regularly,” Vranes said. “But I’ve been around. I’m used to it. I’m here to do what they ask. I accept it as part of my job.”

He shows up prepared every night, which is tougher than it sounds. “It’d be easy to be lackadaisical, to just show up figuring you are not going to play much,” Vranes said. “I try to stay in shape, maintain my conditioning, be ready. If you don’t bring your stuff with you every night, it doesn’t work for you when you need it.”

[Vranes became a free agent at the end of the 1987-88 season. He fully expected to sign with the highest NBA bidder. But, that summer, his agent called him out of the blue to relay an offer for nearly double his NBA salary from a Greek team called AEK. Vranes hesitated. Pro basketball had become more popular in Europe, and the best teams were now offering hefty salaries to entice Americans into the fold. But the European leagues, like American pro basketball during the 1950s, remained very rough around the edges.

The NBA was Vranes’ safest bet, but playing overseas sounded, well, intriguing. And so, Vranes flew to Athens with his wife just for kicks to what was on the table. Team officials promptly rolled their VIP treatment and drove Vranes and his wife to a luxurious home overlooking the Mediterranean, a Mercedes-Benz parked in the driveway. The house, the car, and a lot of money awaited, or so they were promised, if Vranes just signed with AEK.

And so, he did. We’ll pick up the rest of Vranes’ Greek odyssey as part of our next post.]