[By the mid-1980s, basketball was on the rise in Greece. The national team reached the European Cup for the first time in 1985, and the top Greek club teams were now bidding for NBA players to bolster their lineups. But in Greece, like the rest of Europe, pro basketball remained undercapitalized and underdeveloped. “You never know whether you’ll get paid or not,” lamented an American playing in Athens. “You’ve always got problems with the team.”

In the February 1993 issue of SPORT Magazine, freelancer Doug Cress recounted “the nightmares” endured by Americans playing pro in Greece and throughout Europe. Cress, based in Spain, gives us an earful, and 30 years later, his article reads as a baseline account of how far the European game has progressed since.

Cress’ story starts with the Greek odyssey of American Danny Vranes, featured in our last blog post. Vranes told his story in the mid-1990s, and it’s still possible to google the details. But to save you the trouble, here are a couple of key points. One, when Vranes arrived in Athens, he learned about a recent Greek law that made his stay impossible financially. Foreigners had to depart Greece with no more dollars than they had upon entry into the country. Vranes entered with about $1,000. This meant Vranes, who was paid in dollars, had to open a Swiss bank account and hope his team would wire his salary there. It mostly didn’t. And so, in the end, Vranes had to smuggle his pay out of Greece, as noted in this story.

As Vranes later explained, the top Greek teams were affiliated with prominent athletic and social clubs that were proud institutions. If their basketball teams started slowly or proved mediocre, the owners stopped paying the players altogether. But players weren’t supposed to embarrass the club with demands to be paid. It could get you in trouble, as Vranes’ story attests.

The article below starts with Vranes receiving 10,000 Greek drachmas to help him get settled. Here are a few more details. The owner told Vranes to step into a back alley and wait for him to bring the cash. When the owner appeared in the alley, he handed Vranes a duffel bag labeled “bananas.” Vranes opened the bag, rooted through the bananas, and his money was stacked on the bottom. You get the picture. European basketball has come a long way. Enjoy the read.]

****

The last paycheck Danny Vranes received from the AEK basketball team of Athens, Greece, had bounced. His electricity had been cut off for non-payment of bills, his kids had been kicked out of school for non-payment of fees, and the brand-new Mercedes-Benz that he’d been promised by the team turned out to be a nine-year-old Nissan compact.

Worse yet, Vranes, a former first-round draft pick of the Seattle SuperSonics who spent seven years in the NBA, had a hunch the AEK president was mixed up with organized crime. “When I arrived, he gave me about 10,000 Greek drachmas [$1,000 U.S.] to cover my moving expenses,” says Vranes. “But he gave me the money in cash, and it came in a plastic bag hidden underneath a lot of fruit. I figured right then, something was up.”

Vranes’ experiences as an American basketball star playing in Europe during the 1988-89 season were not unique. From slippery lawyers to riotous fans to 18-hour bus rides to unfulfilled contracts, Americans continue to endure nightmare scenarios that neither the US State Department nor Interpol can quite comprehend.

“Every American has a horror story over here,” says center Mark McNamara, a seven-year NBA veteran who’s played in Italy and Spain. “If you haven’t had a problem, then you haven’t played in Europe.”

Says ex-Detroit Pistons coach Herb Brown, “I once had a team director in Spain tell me, ‘Yeah, you’ve got an ironclad contract. But you’ll spend 5 to 10 years in Spanish courts if we don’t decide to pay you.’”

Approximately 350 American basketball players were under contract to European clubs at the start of the 1991-92 season, ranging from Darryl Dawkins in Italy and Michael Brooks in France to Mike Mitchell in Israel and Michael Ray Richardson in Croatia. But with no international players association, few labor laws, and many clubs struggling simply to stay afloat, let alone financially prosper, the opportunities for player abuse are everywhere.

Charles Grantham, president of the NBA Players Association, says he gets calls in his New York office every day from Americans in a jam overseas. He believes an international tribunal must be established to arbitrate and protect the rights of American players, especially if the game is to continue growing internationally.

“It’s time to bring the European leagues into the modern world,” Grantham says. “The teams in Italy and Spain and elsewhere must be made aware that these players are not cattle; they’re human beings, and they should be treated as such. I compare the situation to the way the NBA was back in the early 1950s. From what I hear, the biggest problem is still getting paid.”

True money—or the lack thereof—appears to be the root of all basketball evil in Europe. But in Vranes’ case, his personal situation included an element most are missing: violence. After accumulating only $20,000 in small cash payments over the course of the season (and being forced to launder most of that out of the country on the black market through Switzerland), Vranes did what any stranger in a strange land in a very strange situation would do: He quit AEK, put his wife and three children on the next plane back to the United States, and made plans to follow shortly thereafter.

Or so he thought.

“I went to say goodbye to a Greek friend of mine, who is a stockbroker,” Vranes says. “So, we’re sitting in his office talking, and all of a sudden, these three goons come crashing through the door. They were the AEK president’s bodyguards. One 300-pound guy is holding me, and the other two gorillas start beating up my friend. It was terrible, just awful. They really worked him over. Then they said that if I didn’t play in the next game, a big Greek Cup game, I’d never see him again. And they dragged him out of the office screaming.

“I didn’t know what to do. My friend was gone for a day, and then I got a phone call. It was him, pleading with me to play. He was hysterical. He was begging me to play. He said they were going to kill him if I didn’t.”

Vranes played in AEK’s next game. “I had about 20 points,” he says. “I remember hitting a big shot with about one minute to go, and we won. But I can’t tell you who we played or what the final score was. Obviously, I was a little preoccupied throughout the game, I was a zombie.

“Oh, and get this: After the game, the team president comes rushing out of the stands and tries to hug me. Can you believe it?”

Vranes and American teammate Clint Richardson fled Greece on the very next plane out, carrying with them approximately $33,000 in cash, stuffed into every jacket lining and trouser cuff imaginable.

Vranes’ stockbroker friend was found the next day—alive, but worse for the wear. Interpol swept in and seized the team president, yet AEK remains one of the glamour teams of Europe. And Vranes? He’s now playing for Breeze Milan in the Italian League.

“I don’t really have any problems in Italy,” he says. “Sure, they pay late, but at least they pay. [Teammate] Adrian Dantley can’t handle it, though. He’s Mr. Conservative, and stuff like late paychecks just makes him panic.”

Unlike the NBA, where teams are required to post multimillion dollar operating bonds before the season, most teams in Europe are run on a nickel-and-dime basis at best. Many grew out of small neighborhood sporting clubs—YMCAs, really, and depend heavily on corporate sponsors for their cash flow. Factor in the inevitable front-office graft, mismanagement, and political infighting, and it’s easy to see how American players, especially those on losing teams, get the shaft.

It once took ex-Portland Trail Blazers guard Jeff Lamp three years to get paid by his team, Rimini of Italy. When McNamara played for Unicaja Ronda of Spain, he naturally used the bank that sponsored the club; that is, until he realized the team was taking money directly out of his account for unspecified “fines.” ‘After that, all the money went right under my mattress,” McNamara says.

Then there’s the L.A. Clippers’ Stanley Roberts, who was fined $150,000 and had his contract rescinded by Real Madrid of Spain for missing two practices late in the 1990-91 season. One week later, Roberts was back in the United States for good. “It [was] an experience,” Roberts says. “Would I do it again? No way.”

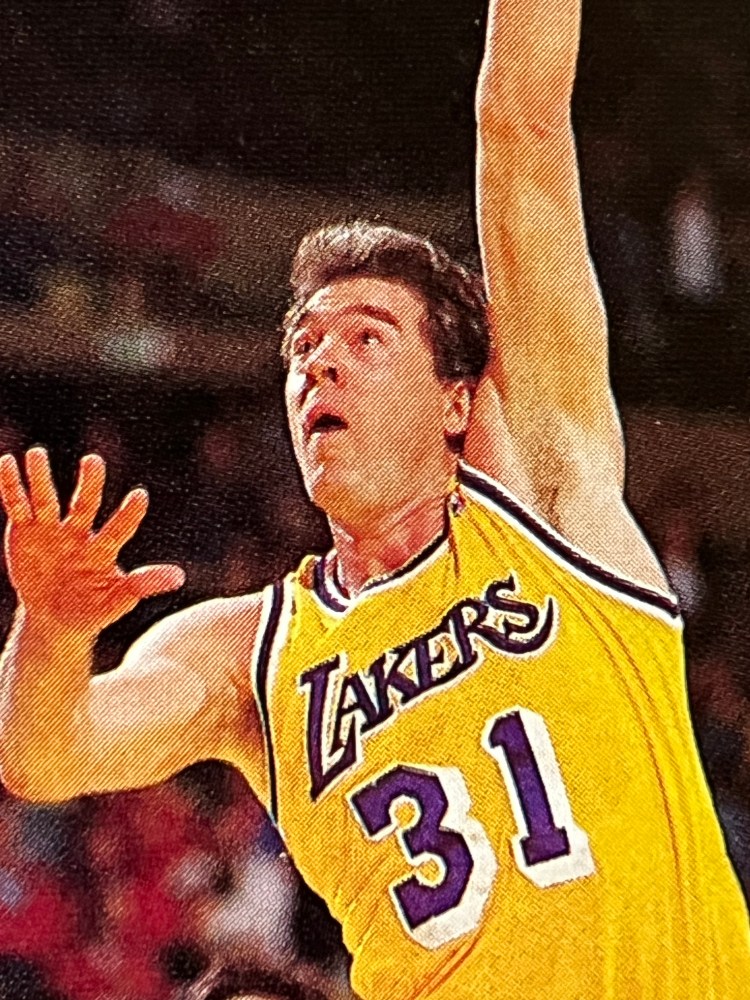

The expectations placed on American players can be crippling. After running through a host of Americans in pursuit of the Italian championship—including the much-publicized acquisitions of Danny Ferry and Brian Shaw in 1989—II Messagero of Rome thought it finally had the answer in ex-Laker Michael Cooper in 1990. But even though Cooper had the best season of his life, he was blamed for the team’s semifinal exit from the playoffs and was sent packing.

“It doesn’t matter what kind of season you had as long as you win in the end,” Cooper says. “I mean, we had an exceptional team—the best since they won the championship in 1983. But the minute we lost in the playoffs, everybody started saying it was a bad season. Everybody started pointing fingers.”

As a rule, players who sign with teams in major European cities, such as Rome, Munich, and Barcelona, generally have fewer problems adjusting to foreign ball. Those cities are more sophisticated. There is a McDonald’s or a Pizza Hut on practically every corner, USA Today is available at every newsstand, and the language barriers are more easily broken down. More importantly, there is a U.S. consulate nearby if the going gets too tough.

But those unfortunate to have to play with teams out in the hinterland can find life trying. Or deadly. When McNamara came down with typhoid fever while playing with Unicaja Ronda in 1986-87, he found the medical care available in the southern Spanish port of Malaga to be, well, medieval.

“I was totally out of it,” McNamara says. “I had to be hospitalized, but I remember, I had all these IVs and machines hooked up to me, and the doctor who comes over to look at me is smoking. He’s smoking! Then he’s saying stuff like, ‘You can’t be that sick, you’re just tired.’ This guy’s puffing away, and I’m dying of typhoid fever.

“Finally, the ashes of his cigarette start falling on my chest as he’s examining me and they’re burning me, and he’s not wiping them off. At this point, I’m delirious. I’m out of my mind. Then my roommate, John Devereux, comes back from checking out the rest of the hospital and says there are rats and cockroaches in the kitchen. He said that back home they would have closed it down.”

Not even the game of basketball itself is much solace for Americans abroad. First off, few arenas in Europe are on a par with small college gymnasiums, let alone NBA-style stadiums. Often, the basketball floor is linoleum or tartan laid down directly over concrete—can you say “tendonitis?”—and the timekeeper, the scorekeeper, and even the referees are wildly unreliable. Even the opposition is not to be trusted.

Earlier in that fateful season with AEK, Vranes says, a European Cup game against a Soviet team was bought and paid for long before the opening tip. “The AEK owners just came into the locker room before the game and said, ‘It’s OK, everything is taken care of,’” Vranes says. “They paid $10,000 to the Soviet team, and this was with guys like Arvidas Sabonis and Rimas Kurtinaitis, and they threw the game. They’d done it before, you could tell; they were throwing balls out of bounds and missing easy shots. We won by 20 points.”

Nor are the fans much help, even if you’re winning. Most courts in Europe are surrounded by tall plexiglass or chain-link barriers to keep the fans in their place, and the players enter and exit the court via long retractable tunnels that shield them from thrown objects. The police, with riot gear and firehoses standing nearby, are not there for show.

When former NBA all-star George Gervin failed to work miracles with TDK Manresa of Spain in 1989-90, the fans pelted him with heated coins and radio batteries. Others have been bombarded with whiskey bottles—hard liquor is sold at all stadiums—firecrackers or lit traffic flares, and even a homecourt victory celebration can get out of hand.

Some places, however, are just depressing. George Singleton, a former Furman star who was drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers in 1984, has split the last eight years between Spain and Italy. Nothing, he says, has compared to the Spanish League’s decision to hold 1985 All-Star game in . . . Portugal.

“Don’t ask me why,” Singleton says. “There wasn’t a team from the Spanish league in Portugal then, and there never has been. And it was a little tiny pueblo, too. But they just told all of us players to gather in Madrid, and then we rode a bus like eight hours to this little town—I can’t even remember the name—to play the game. It was in the middle of nowhere, and this little gym only had stands on one side.

“They had the slam-dunk contest, the three-point shooting contest, and the game all in the same day, but everybody was too tired to play well. It turns out the little town was where they held it because it bid the most money. That’s the way it was then.”

But it’s not just American players who have it rough in Europe—American coaches suffer, too. SuperSonics’ coach George Karl has twice been forced out at Real Madrid—the second time last season for the crimes of an 18-7 record and failing to learn Spanish—while Herb Brown has seen it all in a 19-year career that includes stops in Puerto Rico, Israel, and Spain.

“I’ll never forget being fired by Joventut [Spain] in 1990 with us in first place and the team in the semifinals of the Korac Cup,” Brown says, referring to one of several major European tournaments. “It turns out my assistant coach, who was also my translator, was translating everything the wrong way. He wanted my job, so he was twisting everything I said to the press around the wrong way, making me look bad, like I didn’t care if we won or lost.

“Finally, my wife, who speaks fluent Spanish, noticed one morning when she was reading the paper. But by then the damage had been done.”