[Here’s an article about Pete Maravich during his early days with the Atlanta Hawks. What makes this article so special is its byline: the New York Post’s sports columnist Milton Gross, one of the all-time greats. “When you run with the pack,” Gross said of sports reporting, “you read like the pack. I run alone.” In this longer-form feature story, published in the March 1972 issue of the magazine Sport Scene, Gross gets to run alone a little longer and look a little deeper into Pistol Pete, entering his second NBA season. More than 40 years later, Gross’ longer look remains a good read. In May 1973, or just over a year after this story ran, Gross passed away from a heart attack at age 61.]

****

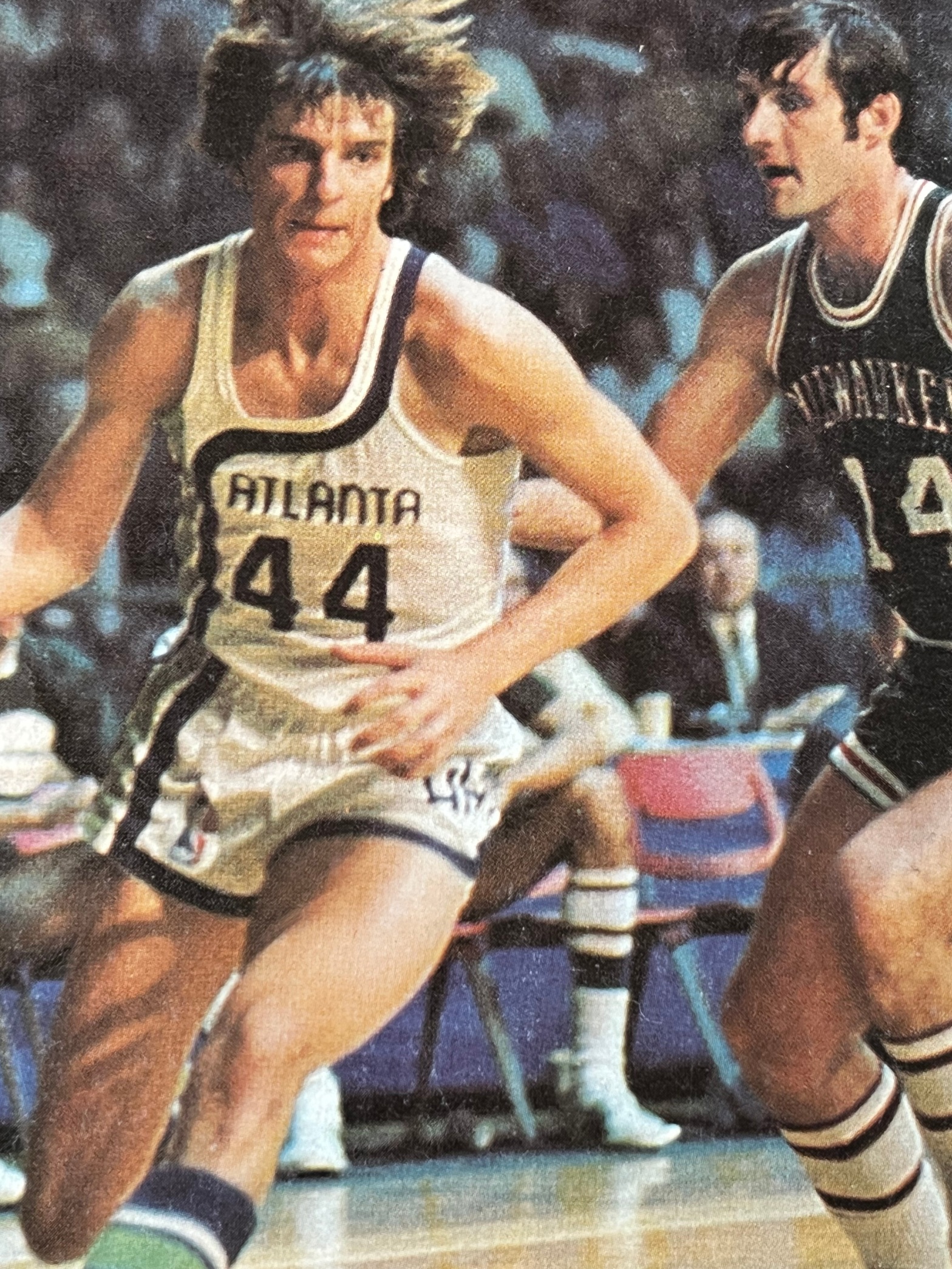

Somehow it seems peculiarly appropriate that Pete Maravich began this National Basketball Association season suffering from mononucleosis. Maravich catches the damnedest things. Hate and love. His personality is as split as his legs, through which he can dribble a basketball as though he were an octopus. You can like him or lump him, but you cannot overlook him.

His teammates on the Atlanta Hawks looked him over, up and down, and all the way around during The Pistol’s first season in the NBA. It began on a note of hate. It ended with growing respect.

“Pete’s going to be better than Jerry West,” said team captain Bill Bridges. “He drives better, he’s quicker, and he handles the ball better. This year is going to be a lot better for all of us. There’s no reason why we can’t start Pete’s second season with the same harmony with which we ended his first.”

Now, a definition of a kind. Mononucleosis is a mildly infectious disease involving an abnormal increase in white blood cells. Most commonly, it occurs in young adults, and it has been called the kissing disease.

So much for definitions. Now for facts. Pete Maravich certainly didn’t catch mono from his Hawk teammates, despite the close proximity in which these large, fast, glandular men must play with each other on the basketball court. The Hawks and Maravich hardly felt like kissing each other last season. They never quite reached the stage where they spat into each other’s faces, but there was more than a growl or snarl or two.

Joe Caldwell ran away and hid with the Carolina Cougars, jumping from the NBA to the ABA. If Maravich was going to get $2 million, Caldwell, a veteran and an all-star, wanted his. He had proved what he could do; Maravich had not.

Bridges stirred up a witch’s brew not because he liked Pete less, but because he too wanted more money. Walt Hazzard sulked for a good part of the season, and when it was over, he had shuffled over to Buffalo. Yet, at the very end, Hazzard said: “[Pete] can beat any man in the league. When he learns to control it, he’ll be a monster.”

And Maravich said: “I could have done without this year in my life. I’ve experienced a lot of things, circumstances nobody knows about, the most hectic grind I’ve ever gone through. Nobody’ll ever know what it was like. If I wrote a book about it, it would sell more than The Sensuous Woman.”

The hell with selling books. Maravich is a sensuous basketball player. Emotions exude from him the way his long hair flies in all directions as he dribbles toward the basket, takes off for a shot and hangs suspended in the air in defiance of all laws of gravitation. Better than selling books, he finally succeeded in selling himself to his teammates, most of whom waited for more than half a season before he proved himself to them.

“A rookie’s got to come to the veterans,” says Hawks’ coach Richie Guerin. “He’s got to prove his worth and earn the respect of the older players. You can’t expect him to be received with open arms. I don’t just apply this to Maravich. It goes for every rookie. So, he’ll know the feeling when he gets it.”

In the case of Maravich, it wasn’t just any rookie. It was Pistol Pete. It was a white among blacks, which, isn’t a big thing in a sport, dominated by Black men. What was bigger, more important, and certainly more difficult to overcome was that Maravich was hailed as the Second Coming before he arrived.

He was going to be the savior. He would pull the Hawks to heights they had never achieved, despite the fact that they were one of the most solid professional teams ever assembled while Pistol Pete was still playing cowboys and Indians at LSU. However, when Pete did arrive in Atlanta, most of what he shot were blanks.

“Last year at this time,” says Guerin, who was almost as much a victim as Maravich, “Pete was resented, but not because he was Pete. More because of the image management presented in the kind of money that was given to him.

“Really, who the hell is worth the amount of money that he is said to be getting? If there was trouble, it was the money, not Maravich. Pete proved himself to be a helluva ballplayer. He had an outstanding rookie year under the most trying conditions. People blamed things on Pete, and that was a great fallacy.

“He made mistakes like all other rookies do, but by the end of the year, he had his game basically under control. He was not rushing and taking shots where he hoped he wouldn’t take the shot and his defense improved considerably. Hell, last year, we were very weak defensively, and in no way can Maravich be blamed alone for that.”

“Look,” said Bridges, a mature NBA veteran, “there were mistakes made all around. Nobody’s completely in the clear. We’re men. We’re pros. We’re playing this game to win, and we’re playing it for a living. Nobody is inclined to blame himself. That’s not natural, and the situation in which we found ourselves for so much of the season wasn’t natural. But as time went on, we came to appreciate Maravich for what he was and for what we knew he could become.

“I admit,” said Bridges, “that at first, I didn’t understand Pete’s creativity. I didn’t understand it at all. Here we’d be doing all those nice safe things, and here came this rookie with all this new stuff. It took us quite a while to work things out, but eventually, we did work them out, and we’re going to be much better off for it, all of us.”

However, when the training season began for the Hawks last September, everything wasn’t dandy, peachy, sweetheart, baby, I love you. There was talk that Pete was being pampered. Or he was malingering, or being a prima donna, or sulking, or still in shock from the trauma of his rookie season. He didn’t play in the exhibition games, and depending upon who told the story, he was either being punished or patted on the head and allowed to take it easy. There was a lot of wondering going on.

Some wondered how does a sore throat take so long to heal. Others guessed that there was nothing wrong with Maravich that a little discipline from Guerin couldn’t cure. They pointed to an incident that occurred during the summer in Florida as proof that Pete needed a stern, guiding hand.

Long before the Hawks got to their training camp in Jacksonville this season, Pete was picked up by the cops and charged with drunk driving. He was fined $150 by a Sarasota judge and put on one-year probation. He had previously been arrested in Tennessee soon after he had completed his final college year when he created a disturbance on a Knoxville street.

“I checked into the whole thing thoroughly, and it was completely blown up out of proportion,” said Guerin of the second arrest. Of course, what Maravich does in the offseason is his business and his business alone. However, being arrested is not exactly a reflection of the maturity that the Hawks are looking for in Pete.

Training camp, at first, promised to be different. No longer a curiosity who had to prove himself, things went along well for Pete in the first week. The Hawks drilled on defense, and Maravich no longer acted as though it was something to which she gave scant attention. For him, it was no longer showtime. It was show-them time for The Pistol.

But then on the eighth day, he developed a fever from an infected throat. His temperature ran 102-103 degrees. He wasn’t able to eat. At first, it was thought he was merely suffering from tonsillitis, but the soreness in his throat hung on, and his fever persisted. On September 21, Pete was hospitalized. The doctors diagnosed his ailment as mononucleosis.

Naturally enough, he did not play any exhibition games, and customers who are either turned on or turned off by the flashy, splashy Pistol formed their own conclusions despite what the Hawks and the doctor said. That is another price Maravich must pay for the money he received.

The chances are it is never going to be any different. Maravich is going to be a target one way or another so long as he laces on a pair of sneakers and appears in his underwear in public doing things with the basketball that have never been done before. He is both the beneficiary and victim of his own talent. He is damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t, because love and hate are so closely allied. Sometimes it is hard to tell when one emotion crosses the line to the other.

He called his first season, “a year of hell.” Others called it a helluva year. Both were absolutely correct. Even his critics can’t write off what Maravich did under last year’s extreme conditions of stress and emotion. He was eighth in NBA scoring with 1,880 points for a 23.2 average, which made him second to Lou Hudson on the Hawks. He helped to get Atlanta into the playoffs, where they were eliminated by the Knicks.

The Hawks started the season with a 6-25 record. Maravich looked more like a soccer player dribbling the ball off his feet and getting himself hung up in a corner than a $2 million savior. However, the Hawks finished fast, giving promise to the fans of good things to come. “I came through it as well as I thought I could,” said Pete.

“Last year certainly wasn’t a disappointing year for him,” said Guerin as he looked back over the turmoil. “He certainly was as good as he could have been under very adverse circumstances. I don’t know how I would have reacted as a 22-year-old kid, if I had to go through a situation like that.”

“The way I see it,” said Bridges after the Hawks had lost in the playoffs to the Knicks, “we lost the battle and the war, but we’re going to be better for it because we came together as a team. We went from one extreme to another, and it had to be the most personally rewarding experience of my life.

“We started in disunity, and we ended in harmony, which may be far more significant than whether we won or lost this particular series. We’re going to be together a much longer time than these five games, and when you can get it all together from where we began, that’s what should be used as a measure of judgment.”

“We expect big things—real big things—from Pete,” said Guerin, “but you must remember that being ill and missing all of the exhibition season and part of the early season again will be a handicap to him.

“Maybe it’s the kid’s fate. Maybe it’s the way the ball bounces. But it looks like he’s had to do everything the hard way. This game is tough enough against the kind of opposition Pete’s had to face and the circumstances in which he had to operate. I don’t know who else could have done it.”