[It’s tough to find anybody who doesn’t hail the memory of Gus Johnson, the former NBA All-Pro who rattled rims and shattered backboards in the 1960s through the early 1970s. He also had a famously big personality, which Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram captured so wonderfully in December 1964 with this classic lead:

Gus Johnson comes across like a high note on a clarinet screaming in an empty hall. He has a gold star perfectly carved in the center of one long front tooth, wears $85 shoes, Continental suits and a tiny hat that sits cocked on the back of his large head. He is at once, in appearance and manner, the kingfish at a fish fry and a little boy on his knees—scared and wild-eyed—watching dice roll in an alley back home in Akron.

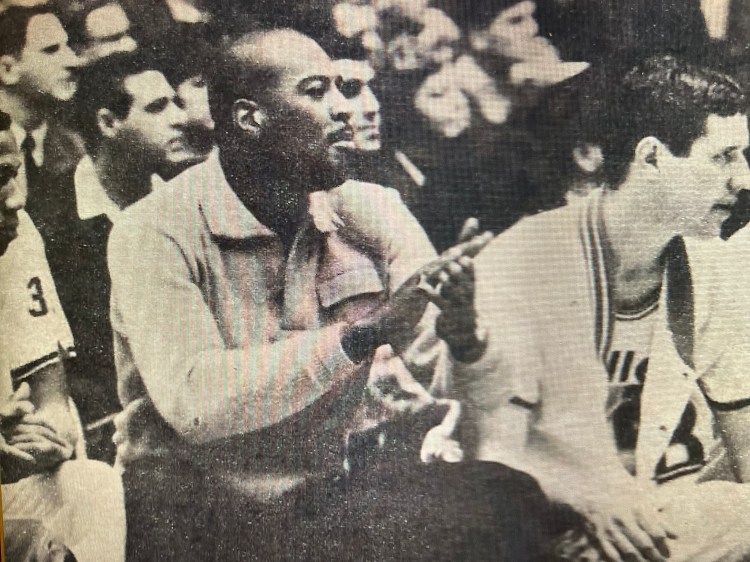

Wanna read more about this “high note on a clarinet screaming in an empty hall”? Have I got an article for you. It comes from my partner Ray Lebov. He recently shared with me this profile of “Honeycomb” from the December 1966 issue of SPORT Magazine. The byline bears the name of the great Myron Cope, better known for later calling Pittsburgh Steelers games.

One more thing. Ray and Mike Shearer assemble the very best NBA reporting of the day in Basketball Intelligence. If you want to stay current on the association, there is no better source of information than BI. Subscriptions are reasonable, and the rewards are inestimable.]

****

When basketball people reminisce on the plays that Gus Johnson has executed, listeners may be forgiven if they surmise that Johnson lived 100 years ago and that, like many legends, he has acquired a cult who assumes a license to embroider outrageously his actual deeds.

“I recall a rebound he made against Gonzaga in Spokane, Washington,” says Joe Cipriano, who coached Johnson at the University of Idaho in the 1962-63 season. “He grabbed the ball above the rim, with his back to the board. Before he came down, he spun around and threw a behind-the-back pass that traveled three-quarters the length of the floor. Caught a forward in stride, and the guy laid it up.”

Did Johnson actually see the forward? Did he aim the ball at him?

“Oh yeh,” says Cipriano, calmly. “He saw him. Of course, I told everyone we worked on that play quite a bit in practice.”

The truth, of course, is that unheard-of plays come to Gus Johnson as instantaneously as the emperor Julian heard marching orders from the gods. Indeed, Gus himself calls them “God-given,” and they sometimes take the form of shots that nobody can recall ever having seen.

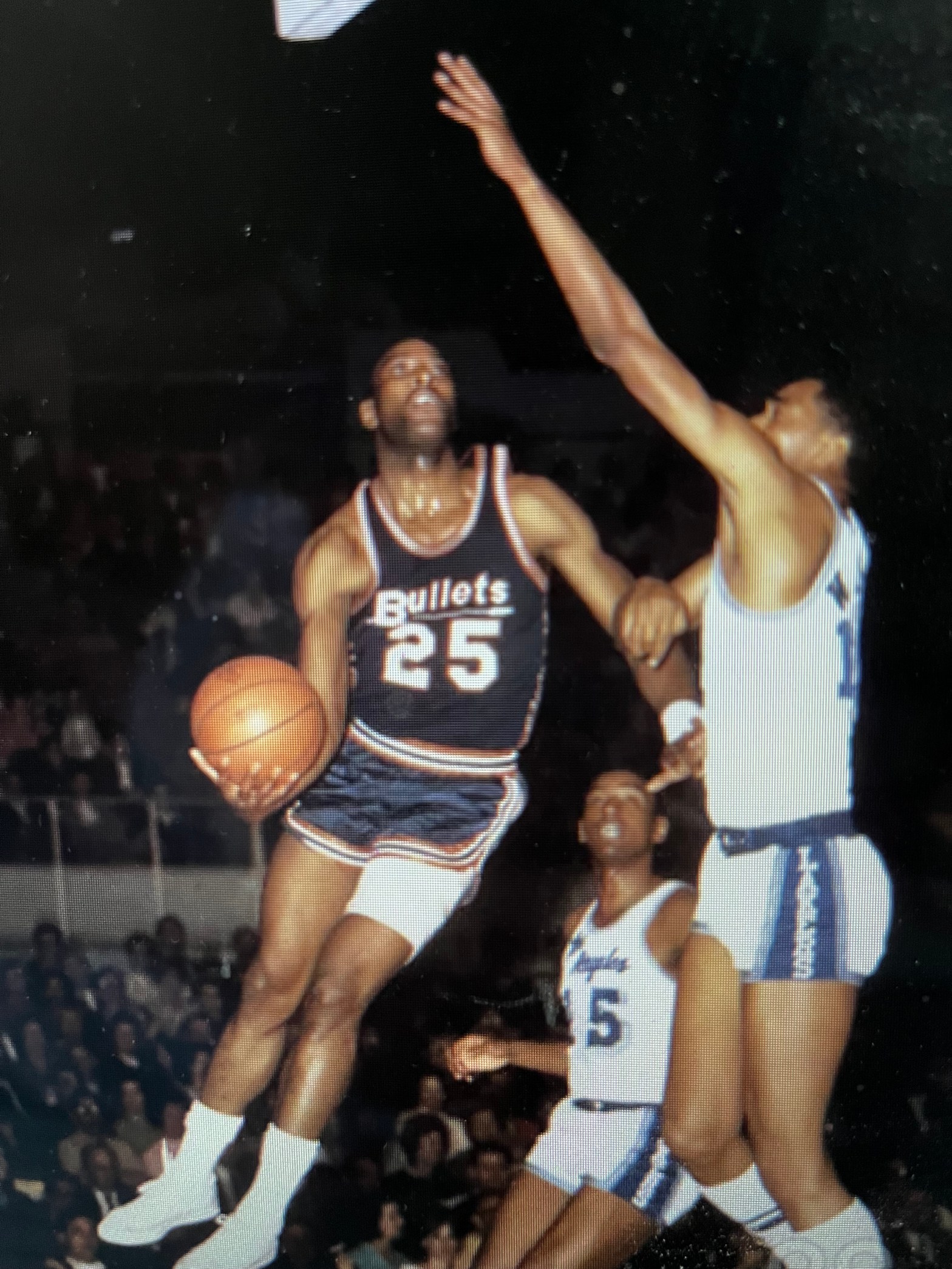

For slightly more than three years now—or to put it another way, during the time Gus has played for the Baltimore Bullets in the National Basketball Association—the art of shooting has been carried to unpredictably gaudy theatrics. In Johnson’s hands, it is wild pop art, and it has become commonplace for pros to remark, “Only Gus Johnson could have made that shot.”

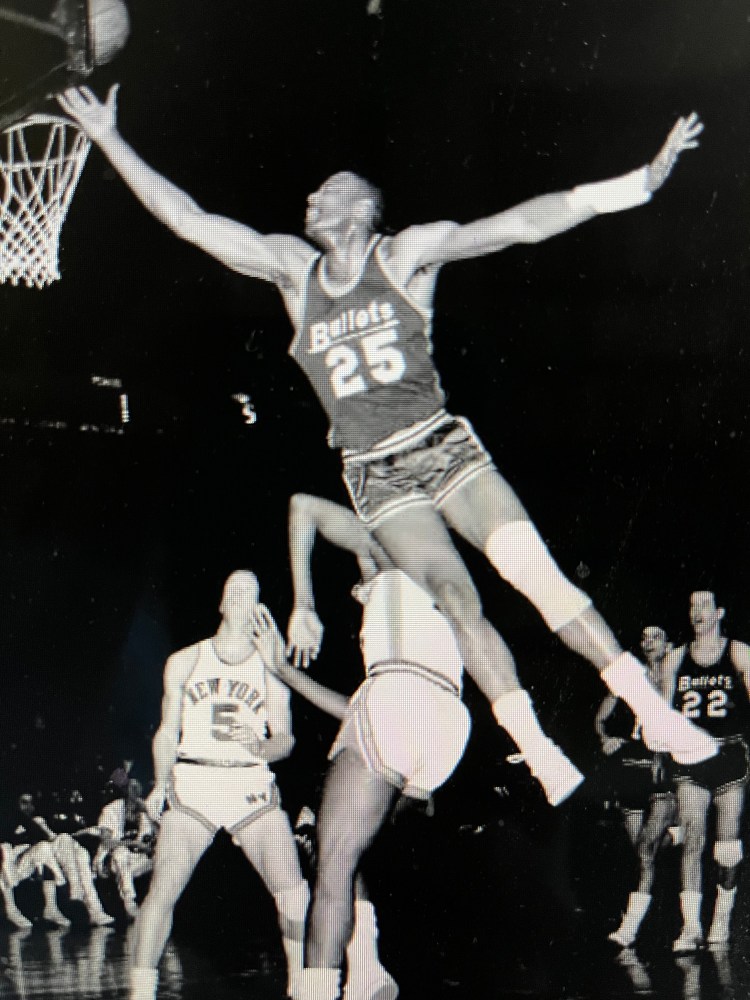

Gus himself would be the last to disagree. He recalls that in a summer game at Baltimore two years ago, he pounded down-floor with the ball and at the free-throw line catapulted in a great arc to the basket. With both hands he stuffed the ball. It was an unusual shot, he says, because all the way from the free-throw line he carried an opponent on his back.

“I’m a crowd pleaser,” says Gus, appraising his work at forward for the Bullets. “Some of the things I do sometimes amaze me. I don’t see how I do them.”

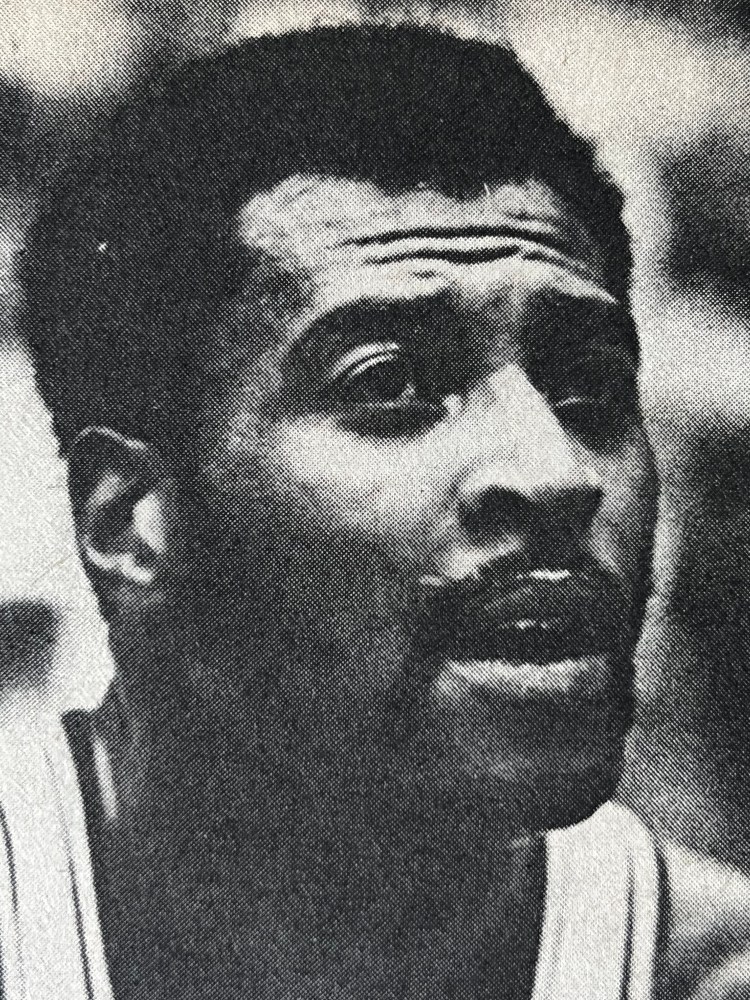

A dark, muscular man with regular features, Gus is listed at 6-6 in the NBA Guide, whose editors may have measured him after he had started his jump shot. He says he really stands 6-4 ¾, which for an NBA forward is undersized.

Ballplayers call him Honeycomb. “My college coach gave me that name,” Gus explains. “He said I was sweet.”

At one time or other, Gus also has been known as The Windmill Dunker, Bloody Gus, Gus the Great, the Man on the Flying Trapeze, and Hercules—all cognomens intended to convey the idea that Gus’ strength is as the strength of 10 and his acrobatics of a sort that would have made P.T. Barnum’s eyes pop. Between the free-throw line and the rim, his body well up in the air, Gus wriggles and thrashes, executing more maneuvers than an astronaut on a space leash. Joe Cipriano most succinctly analyzed Gus’ ability to postpone the law of gravity. Explained Cipriano: “Gus says, ‘Legs, jump!’ And they say, ‘How high, boss!’”

Along the avenues of Baltimore, Gus is as smooth as silk because that is what he is dressed in—from his continental suit right down to his shirt, socks, and underwear. He would rather blow a layup than be found wearing cotton. Moreover, lest anyone mistake him for an average citizen, he carries an advertisement of his eminence in his mouth—smack in the front where an upper tooth is engraved with a gold star in a gold border.

Gus has been wearing his false tooth since his rookie season, when Walt Bellamy, then his teammate on the Bullets, clouted him in a scrimmage. “The Bell and I had had some differences, and then I came in for a layup and his elbow caught me and busted my tooth in half,” Gus says.

He rattles on at a furious clip, in a deep, mellifluous voice. “I had to get a new tooth, so I decided I wanted a design on it. This just came over me. A star for a star. It fits my character.”

Well, said Gus’ dentist, a frustrated Michelangelo, why not?

“It’s become sort of a legend,” Gus says. “Everywhere I go, people want to see my star—grownups as well as children. Bob Ferry says, ‘You can trust your car to the man with the star.’ But I’ve been thinking about taking it out. Maybe put a plain tooth in. I’m tired after games, but there are always kids around, wanting to see the star. ‘Lemme see your star’—like I’m advertising toothpaste.”

Now in his fourth season, Gus has made the NBA’s second All-Star team the past two years, and there are those who say he would have emerged as the league’s most valuable forward last year had he not been crippled by a serious injury to his left wrist. Gus regards this line of reasoning as unimpeachably sound. “Here I was, I played in only 42 games, and I still made the All-Pro team,” he says. “It was fantastic. Making all-pro with only half a season—that was fabulous. So evidently, I left the impression I was an upcoming superstar.”

More specifically, Gus left the impression that he not only could shoot accurately from incredible angles, but also that he was willing to feed and work hard on defense. In his second season, he played himself down from 252 pounds to 218. Kevin Loughery, the Bullets’ playmaker, points out that Gus specialized in the type of pass that is even more important than the last pass to the man who scores. “The big one is getting the rebound and getting off that first pass,” says Loughery.

As hard as Gus played, there were detractors who insisted he was inconsistent—that he did not turn in the big performance frequently enough. “It’s kind of an unfair rap,” says Loughery. “A guy who is flashy and exciting always gets this rap, because people are disappointed if he doesn’t make the fantastic stuff shot every game.”

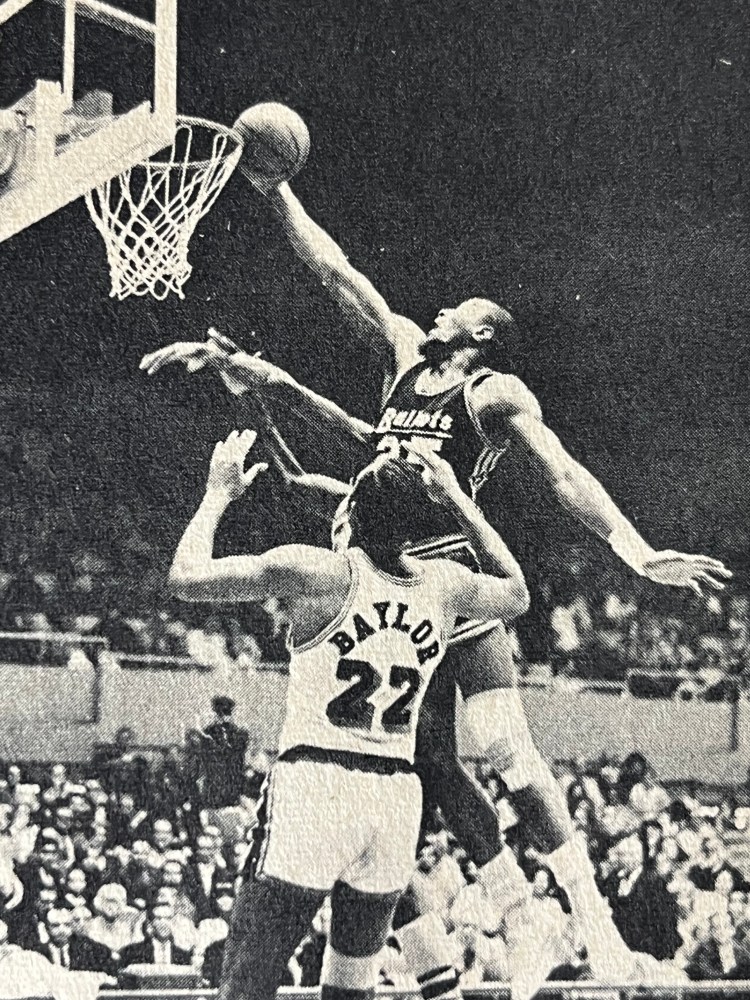

At any rate, the Bullets found that one way of ensuring that Gus would perform to the hilt was to remind him of Jerry Lucas. The Cincinnati forward stands one team above Gus on the All-Pro squad. “I don’t resent the guy,” Gus insists. What he resents is having played in Lucas’ shadow since his high school days.

Lucas of Middletown dazzled the entire state of Ohio. While Gus enthralled a sparse population at the University of Idaho, Lucas made All-America at powerful Ohio State. The year of Gus’ debut in the NBA, Lucas was named Rookie of the Year. “They didn’t know anything about Gus Johnson,” Gus says. His implication is that honors are automatically bestowed upon Lucas on the strength of his buildup.

In any case, Gus can be counted upon to go all-out against Cincinnati, and one night, just to make sure he did, the Bullets posted Lucas’ picture on his locker. A caption had Lucas saying: “This is my night to get you.” Gus roared from the locker room and scored almost 40 points.

Not surprisingly, some who hear Gus chatter on about himself come away with the impression that he is insufferably egotistical, and Gus does not shrink from the charge. Logically, he reasons that to be a superior athlete, one must possess much ego—self-confidence, if you will. More than just a superior athlete, Gus also is a showman, a rule that requires still more ego and a good deal of verbosity.

But while he is unstinting in his admiration for his own feats, he is by no means so self-centered as to be obnoxious. Courteous and good-humored, he is the soul of agreeability constantly chanting, “Right, right,” as listens to others holding the floor. “He’s a great big, likable guy,” says Bullets trainer Bill Ford.

Inasmuch as Gus’ astounding leaps from the free-throw line to the basket are just about the closest thing on the market to a Superman takeoff, it is not surprising that kids love him. Last summer, Gus traveled to Kent, Connecticut, to work as a basketball instructor and group leader at a children’s camp. The boys and girls at Camp Leonard-Leonore were from wealthy Long Island families who had enrolled them in camp for eight weeks at a cost of $800 per child. Not all of the kids were immediately impressed by a pro basketball star. After Gus had been there two weeks, he told a visitor:

“Some of these kids said to me: ‘What do I need basketball for? My old man will take me into business. When my old man dies, he’ll leave me a million bucks.’ Well, I told them: ‘Even if you got a million, it’s a beautiful thing to be fit.’ I put my heart into this job. Today, there’s not one kid in this camp who won’t do whatever I ask him. It’s a great feeling.”

Gus shared his comic books (“my intellectual stuff”) with the kids in his group—Gus’ Grenadiers—and when anyone got out of line, he held up his two huge fists and asked, “Want to test my Eighty-Eights?” The kids giggled. Basketball quickly replaced baseball as the camp’s most-popular sport. A tiny fellow named Mitch, 11, explained the shift in popularity, speaking in very proper terms. “I never thought pro basketball players had much emotion,” Mitch reflected, “but Gus has a sparkling personality.” So much for those who call him an insufferable egotist.

When his summer at Camp Leonard-Leonore came to a close, Gus repaired to his home in Akron, where he dug in prepared to wage a holdout against the Bullets’ front office. The previous season he had been paid about $18,500, but now he wanted a good deal more.

“I know I’m a drawing card,” he said. “When people come to see the Bullets, they come to see Gus Johnson. Time the club realized it. When people want a Baltimore player to speak, they ask for me. I speak very fluently and plain and clear. I’m understandable.”

A $30,000 contract would be about right, Gus judged plain and clear. He was going on 28 already, and his plan was to become a superstar right away and then, having had a taste of superstar pay, retire at 30 and then go into real estate. And just imagine, not 10 years ago, he, Gus Johnson, had been lying around pool rooms looking to hustle drunks.

In central Akron, a tough neighborhood, Gus moved with a flourish. Until he suffered a broken knee, he played linebacker for Akron Central High with a style that caused teammates to call him Bloody Gus. Basketball, however, was his meat, and he aspired to become a Harlem Globetrotter. Drilling himself in the art of flash, he would paint a white spot on his wall, whip a blind pass at it, and whirl to see if he had hit the mark. His passes in high school were sensational. “I had—whaddaya call it?—peripheral vision, and when I let those passes go, I could feel where the man was,” Gus says.

In his senior year, the high school team included not only Gus but a 6-9 player and another who was 6-8. The latter was Nate Thurmond, who today, of course, is the 6-11 center of the San Francisco Warriors. Still, because Gus’ legs listened well when he told them to jump, he played center.

Gus got his diploma, thanks to his basketball coach, Joe Siegferth, who made him obey his teachers on pain of being thrown off the squad. (“He’s like my second father,” says Gus.) Dozens of college offers poured in, but education did not interest Gus. “All I wanted to do was hang out with the fellows and shoot pool,” he says. “I was one of the best pool players in Akron. I borrowed a couple dollars from my mother and stayed at the poolroom till it closed.

“One night, I borrowed five from her, and won $300 and came home and threw it on the bed. My mother said, ‘Where’d you get that?’ When I told her, she didn’t like it. She’s a real religious woman.” Gus himself was not without virtue. Besides hustling men who reeled into the poolroom from the saloon next door, he taught Sunday school.

During the two years that followed his graduation from high school, Gus gave college ball a fleeting try but dropped out of Akron University after one semester and, for a brief time, held a job in the county treasurer’s office in Cleveland. But he confesses, “I didn’t like work, and work didn’t like me.”

Still, a white West Virginian named George Swyers, one of the few men around who cleaned up on Gus in the poolrooms, undertook to persuade him to play college ball. Specifically, Swyers wanted him to play for an old friend Joe Cipriano at Idaho, and together with Cipriano, had worked out a plan that would place Gus in Boise Junior College for a one-year academic shape-up and then forward him to the state university at Moscow, Idaho.

“I thought Swyers was crazy,” says Gus. “I was livin’ good. I had my own car, I lived with my parents, I didn’t want anything. So why should I go to school? But I said, ‘George, I’m considering your offer.’” Gus does not spell out the offer, simply adding, “We finally came to agreements.” The decisive factor, says Gus, was that he at last realized he would never amount to anything if he stayed in the poolrooms.

****

As Gus saw it, the rural west held both an advantage and disadvantage for him. Far removed from Akron friends, who frequently beckoned him to a night on the town, he would be able to concentrate on studies. On the other hand, Idaho was white; Gus was apprehensive. Boise’s coach, George Blankly, foresaw that Gus might be lonely and phoned to ask him: “Do you have a girl?”

“Yeh. Been going with her five years,” Gus answered.

“Do you love her?”

“I imagine I do.”

“Have you ever thought of getting married?”

“Hell, no.”

Nevertheless, Blankly had given Gus something to think about. Gus asked the girl, Janet Connelly, if she thought marriage was a good idea. An excellent idea, she replied. So, Gus went to Boise with the bride.

Entering a white society, Gus fully expected that his Eighty-Eights (as he chooses to call his fists) would be kept busy. “I went out there with a chip on my shoulder,” he says, “but the people were so warm and welcoming, we couldn’t get over it.”

Living in a campus apartment, he was unaware that a Black neighborhood existed in another part of town. It was two months before he saw another Black man. “I saw him on the sidewalk while I was driving down the street,” Gus remembers. “I stopped my car in the middle of the street and jumped out and pumped his hand. He thought I was crazy. I said, ‘Hey, baby, it’s beautiful to see some soul, I been here two months and haven’t seen any blood.”

Meanwhile, George Blankly became curious to see what sort of merchandise he had imported from Akron. He called Gus to the gymnasium and said, “Can you shoot? Can you hook?”

“Sure,” said Gus.

“Well, show me.”

“Which hand?”

Here was a cocky guy, thought Blankly. “Okay, the left hand,” he said.

Gus swished a 25-footer. Blankly clapped himself on the forehead. Then, Gus swished a right-handed hook, and Blankly rushed to a phone to tell Joe Cipriano that Idaho had a find.

At Boise and the next year at Idaho, Gus was crowned “Gus the Great” by sportswriters and was adored by a region wild about basketball. “One paper had a picture of me shooting into space with guys hanging onto my waist,” says Gus, pleased by the memory. “In one game, I had 43 points at halftime, so they took me out and didn’t put me back in till the last five minutes, and then I fed my teammates an unbelievable array of assists. The fans couldn’t believe it. The newspaper said, ‘We got the Globetrotters right here.’”

After one year at Idaho, Gus departed, unable to resist a $15,000 salary offered him by Baltimore. Having whipped in and out of Akron University four years earlier, he was eligible for pro ball, and now as an NBA rookie, he proved to be both a delight and a source of anxiety to the Bullets.

Gus himself says he was cocky then. Before he reported to the Bullets, he told the boys back in Akron that he was a cinch to cut a swath through the NBA. But as soon as he found himself on the same court with men he had known only through headlines, he became jittery and played badly.

To Bob Leonard, then the Bullets’ coach, Gus wondered aloud if he really belonged in the NBA. Replied Leonard: “If I didn’t believe you could do the job, you wouldn’t be out there starting.” Reassured, Gus went on to average 17.3 points and 12.2 rebounds in his first season.

Soaring over the heads of NBA giants, he stamped himself an electrifying addition to the league. In a game at San Francisco, Gus flew to the basket with Guy Rodgers clinging to his shoulders and stuffed the ball. The weight of both men cracked the hoop. “Are you as strong as you look?” someone asked Gus.

“Stronger,” he answered.

****

Yet it was said in Baltimore (and is still said today) that Gus Johnson was marked for trouble. Fifteen thousand dollars seemed a bottomless fortune for him, and he spent every penny of his salary. “I blew a lot of money on ridiculous things,” Gus admits. “I had manicures and facials. Mohair suits. Going out with the team, I’d take the tab—sometimes $300 or $400. ‘Everything’s on me boys.’ One night in Akron, Nate Thurmond and I together spent something like $1,100 buying all the guys we knew.”

The more Gus reflected on his athletic prowess, the more guilty he felt. I’d see guys on the corner with their eyes blowed out or their legs crippled, and I’d give ‘em 10 bucks. I’m proud of my body. When I looked at these people, I get sick. I go to hospitals to visit patients, and every time I go, it takes a little more out of me.”

A year after he had first begun collecting a paycheck from the Bullets, Gus was startled to realize that he had not banked a nickel. Moreover, his difficulties mounted in his second season when he began to absorb fines for being tardy to practices. One Sunday afternoon, explaining that a parade had delayed him enroute to the arena, he arrived barely five minutes before game time, prompting Paul Hoffman, then the general manager, to fine him $500.

Gus’ heart was bitter but, luckily, his legs kept saying, “How high, boss?” In St. Louis, he soared to the hoop and, with both hands, jammed the ball so hard that his forearms tore the rim from the glass backboard. The backboard shattered, and a large chunk of glass was torn from it. The rim, falling to the floor, glanced off the foot of a Bullet player, Si Green, who had to sit out the rest of the game.

“They delayed the game 25 minutes,” Gus says. “The announcer said, ‘This has got to be the strongest man in the NBA. He breaks one basket a year.’ You could hear the people saying, ‘Look how strong he is.’ I was walking around with my chest out. The guys were calling me Hercules.”

Improving on his rookie performance, Gus, averaged 16.6 points and 13 rebounds per game in his second season—and got back all but $50 of the $500 fine from the front office. The next summer, however, his future fell into doubt as rapidly as he had soared to prominence. Playing in the annual Maurice Stokes Benefit Game at Kutsher’s Country Club in the Catskills, Gus suffered a bruised left wrist in a mid-air collision. He thought little of the injury until, in the second game of the 1965-66 season, he collided with Cincinnati’s Jerry Lucas. A large, menacing red knot formed in his wrist.

“You can imagine me showin’ out real red,” says Gus, stressing the gravity of the injury. His wrist was only dislocated, not fractured, but the nerve running across the navicular bone had been deadened, depriving him of the flexibility he needed for his left-handed shots.

He was on the operating table for three hours, as the surgeon tried to realign tendons around the navicular. It was a risky operation with the chance that Gus would lose mobility in the wrist. But it worked. He started playing again in January and finished up with 677 points for the season.

Now, there is no telling whether Gus will rise to the superstar status he envisions for himself. The very fact that he is the greatest mid-air performer in basketball prompts the suspicion that his game is too reckless for his own good. Says Kevin Loughery: “Moving your body around in the air, you gotta come down in awkward positions. To play the game the way Gus does, I think you gotta get hurt.”

Bill Ford, the trainer, says flatly that Gus will have trouble with his wrist as long as he plays, though Ford speculates with determined optimism that his performances will not suffer. Perhaps the greatest danger to Gus’ career lies in his own knowledge that re-injury is a prospect for him. “It’s always on my mind,” he admits, “I can’t afford to be as reckless and abandoned as before.” Alas, isn’t recklessness the very essence of Gus Johnson’s success.

****

Pro basketball has taken Gus out of Central Akron. Today he lives with his wife Janet and baby Stephanie on the comfortable west side of town in a house that has four bedrooms, a den, and a rec room. His holdout, which lasted only until the third day of training camp, won him what the club describes as “a very nice raise.”

But whatever his salary amounts to, he is not likely to squander all of it as he once did. “I’m a carefree guy,” Gus says. “All I wanted to do was play and make the big buck. But I’ve changed. I’ve proven I’m a man. I’m still around, and I made All-Pro on 42 games. They just don’t pick anybody you know.”

Triggered by the magic words, all pro, his voice grows stronger and his words come faster, and suddenly there seems no chance that in the interest of safety, he will abandon the style that made him Gus the Great. ”You don’t see Bill Russell or Wilt Chamberlain gliding through the air and shoving it in there like I do,” Gus says firmly.

[As some quick bonus copy, remember the mention of Johnson’s resentment of archrival Jerry Lucas? Here is Johnson’s thoughts on playing Lucas—and vice versa. It comes from a November 8, 1967 article by Baltimore Sun’s Seymour Smith, whose simple lead was “Overheard between dribbles.”]

Gus Johnson: “You have to play Jerry Lucas nose to nose. The guy’s a great shooter. Great rebounder. But he is not a good driver. Strictly an inside man. You got to belt him now and then. He doesn’t like to get hit. I play a wide open, running game. They tried to rough me up my first year. They found out.”

Jerry Lucas: “Gus Johnson doesn’t give ground, and he likes to brace up against me. You have to mix up your moves or he’d smother your jump shot. Gus uses his hands a lot. To a referee, it might look as if he’s just resting his hands on an opponent. But the guys so strong, his hands are almost effective as an iron bar when it comes to keeping you from driving.”