[For years and for no good reason, Cazzie Russell has been staring at me in my office from a nearby glass cabinet. His mug, mostly expressionless while dribbling a basketball, is on the cover of the January 1966 issue of the magazine Dell Sports that tops a stack of magazines stored away in the cabinet.

Last weekend, I had occasion to rummage through the cabinet and picked up Cazzie the Magazine, trying nostalgically to remember the articles inside. Mostly college stuff, except for an interesting piece about the Los Angeles Lakers’ rising young superstar Jerry West. Doubly interesting, the article is written by Leonard Koppett of New York Times fame and the author of the classic NBA history 24 Seconds to Shoot. In the article, Koppett offers an interesting period perspective on West that passes the test of NBA time. Definitely worth passing along. So, here you go. Enjoy!]

****

Listen to a man who should know:

“Jerry West,” he says, “is the most explosive offensive force in basketball today.”

The speaker is Richie Guerin, player-coach of the St. Louis Hawks. As a backcourt man for the New York Knickerbockers and Hawks for many years, Guerin knows firsthand what it means to try to play against West. It is a knowledge that onlookers can only surmise. And, since last January, Richie has also had to look at West through the eyes of a coach whose team is being kept out of first place by West’s efforts. The Hawks finished a strong second in the National Basketball Association’s Western Division—and Jerry West’s Los Angeles Lakers finished first.

It used to be, you’ll remember, “Elgin Baylor’s Los Angeles Lakers.” Then it was the “Baylor-West Los Angeles Lakers.” The latter is the outfit that came within a fraction of an inch of derailing the Boston Celtics in a final-round playoff in 1962. (A shot by Frank Selvy hung on the rim with the score tied—and no seconds to play—and fell off, and the Celtics went on to win that seventh and deciding game in overtime.)

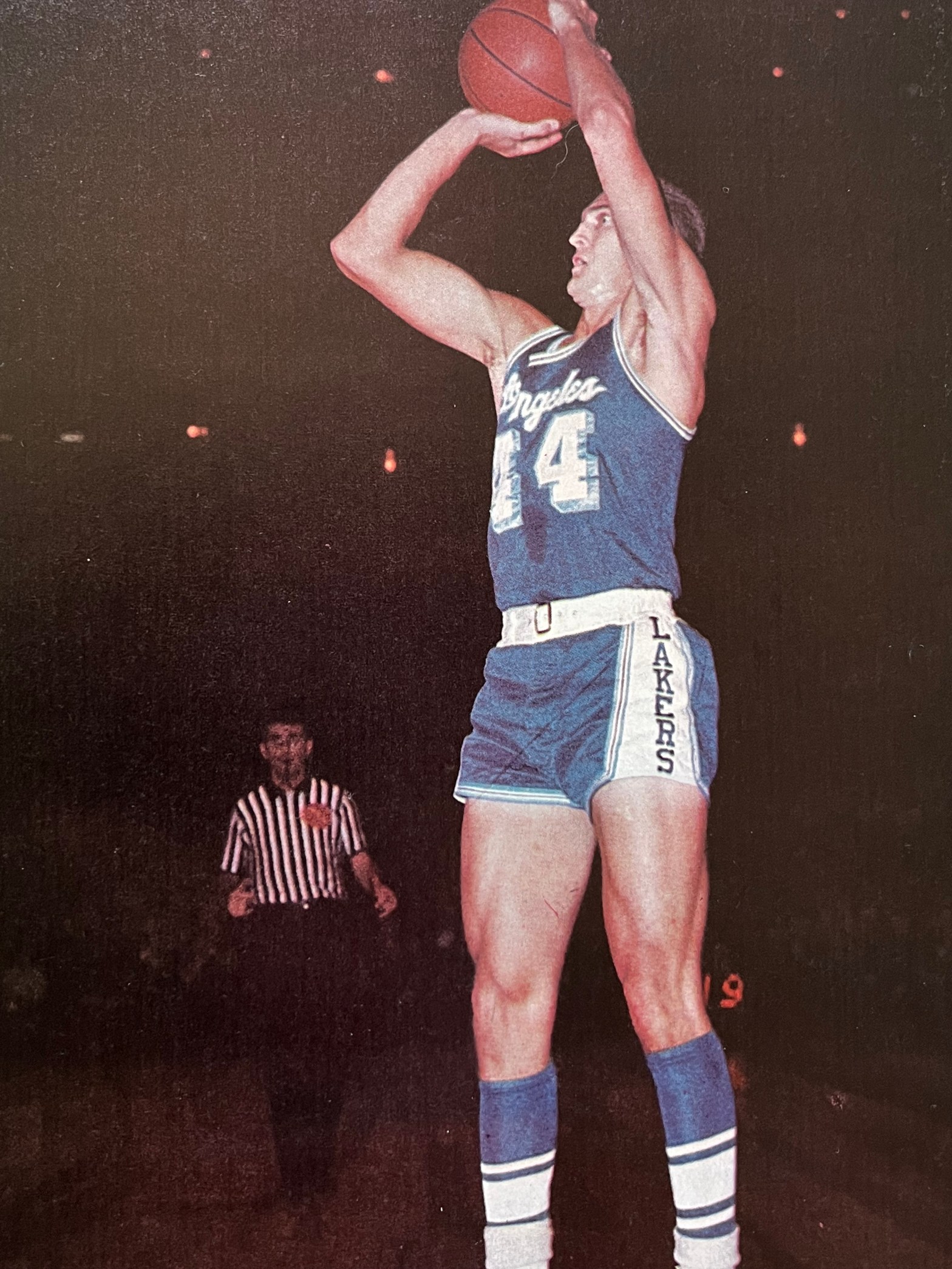

The 1965 playoffs, however, lifted West to a new level of stardom. Baylor couldn’t play (except for five minutes of one game) because of a serious knee injury. Suddenly the public, through the heightened publicity that accompanies a playoff, began to grasp what those close to the league had been coming to realize more gradually: that Jerry West, in his fifth professional season at the age of 26, was still getting better and better . . . and better . . . and better.

And now, in the NBA’s 20th season and Jerry’s sixth, he has reached a new status: star among stars and possibly heir to Bob Cousy’s vacated title of the ordinary man’s favorite.

When Cousy retired after the 1963 season, a certain type of hero-image was lost to the NBA. It is no disparagement of Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, Bob Pettit, Dolph Schayes, or other dominant stars to point out that the ordinary person finds it hard to identify with men so tall. In a game like basketball, where height is so obviously an advantage, players, who are more than six-and-a-half feet tall may be respected, admired, envied, honored, and appreciated, but they don’t generate the emotional involvement that makes the fan feel “that’s ME out there.”

Cousy did that. At 6-1, he was actually much taller than the average man, but among the giants of a basketball court, he seemed like a small man, and his triumph was the normal-sized human’s triumph.

West is a lot taller than Cousy. He’s 6-3. But again, by comparison and by assignment (to the backcourt), he’s “a small man.” He’s only an inch shorter than Baylor—but Elgin, because he plays frontcourt and because of his tremendous strength and rebounding ability, is classified as “a big man” in the fan’s mind. By the same trick of perspective, he seems bigger than he is, just as West seems smaller than he is.

There’s one other player whose name has been linked with West’s since his college days, who is also “only” 6-5 and who does play backcourt: Oscar Robertson of Cincinnati. Many people consider Oscar to be the most-talented basketball player of all—but for that very reason, Oscar misses arousing a full-scale sense of identity in “average” onlookers. Oscar is so effortless so often under the basket, so obviously able to hold his own among the giants, so all-fired perfect that one is awed rather than involved.

All right, then. West is hot stuff. Why? How?

Here again, he is in tune with the average man. Jerry does three things all basketball players strive to do at all times: shoot, move, and concentrate. The only difference is one of degree. He does them at an unbelievable peak of efficiency.

His most-important single asset is shooting ability. It has two aspects, accuracy and range. Because he can hit the mark so often, his “good shots”—shots from a position where his chance of scoring is very high—are more numerous than the most players. And because he can find his own good shots at distances up to 30 feet from the basket, he can always manage to get free for a shot.

His marksmanship is truly remarkable. Statistics concerning this need some interpretation. Most centers and other big man approach a .500 field goal-attempt percentage these days, because most of their attempts are from point-blank range. Some small men who seldom shoot outside, but attempt to score only on layups off a drive, also can make half their shots. Ordinarily, however, a backcourtman operating at normal ranges, depending on jump shots, sets, and occasional drives, is doing fine if he makes one-third of his shots.

West, last year, shot .497 from the floor. Only Wilt Chamberlain, Walt Bellamy, and Jerry Lucas did better—and only a shade better at that. Put another way, Jerry was good for a point every time he shot.

The same soft touch and guided-missile accuracy make him an outstanding foul shooter with an .821 percentage, and this becomes important in two ways: one, because he’s so sure, it doesn’t pay to foul him, and he also gets a disproportionate share of [traditional] three-pointers; and, two, because he’s so good under stress, his free throws take on added value in the closing moments of a game, when fouling increases and games are won or lost on the foul line.

West’s shooting ability is so great, in fact, that he has made “gunning” respectable in his case. It took him his whole rookie year to realize that he was supposed to take all shooting opportunities as a pro. He was, at first, reluctant to shoot too much. No one suggests, even in jest, that he shoots too much today—even though only half a dozen players in the league shoot as much. (There is an interesting comparison with Baylor, his teammate. Last year, Baylor took 247 more shots than West and scored 283 fewer points—and Baylor still wound up with the fourth-best scoring average in the league, 27.1 points per game. West, with 31 per game, was second only to Chamberlain’s 34.7).

But accuracy, no matter how great, can’t come into play during intense competition against top-level opposition unless the shooter can get free. Here we come to West’s second great asset, quickness. This isn’t the same as running speed; it’s quickness of hand and quickness of first step in beginning a movement. West is so good at these things, and at timing his jump, that no one can cover him effectively man-to-man; and while a big man, who can’t be covered individually, is subject to gang-defense tactics, a backcourt man can’t be.

A defender can’t play too close to West, because Jerry can drive past him if he does. A defender can’t give him the usual freedom beyond 25 feet, because West can hit from out there.

Fast and accurate at all times, West comes to a peak in clutch situations. His last-minute heroics are legend, built as much on his ability to steal passes or deflect dribbles as on the baskets or free throws that follow. Fred Schaus, who coached Jerry at West Virginia and has coached him ever since at Los Angeles, says he has never seen a greater clutch player, and countless basketball people agree with him.

This quality is a direct result of Jerry’s tremendous competitive urge, combined with his endless concentration and effort. He is not the shooter that he is by accident: He keeps practicing all the time, perfecting a slightly different shot from a different angle, between seasons as well as during seasons.

As a passer and playmaker, West is outstanding, but not Cousy or Robertson. Defensively, he is as good as anyone can be (in his size range) when necessary. Over an 80-game season, of course, he does not play top-flight defense at all times. His responsibility is to concentrate on offense, because that’s what his team needs from him; and under pro conditions, no man can play with equal intensity at both ends of the floor 40 minutes a night, four nights a week. But, in particular game situations, when he does concentrate on defense, he’s one of the toughest guards around.

In last year’s playoffs, with Baylor out, West carried the Lakers past a tough-and-improving Baltimore team and gave the champion Celtics fits in the final round. He averaged 40.6 points a game, a record for the playoffs. When you realize that former playoffs were dominated by people like George Mikan, Schayes, Cousy, Chamberlain, and Baylor, the full significance of such a record is clear.

Even more amazing is the fact that West once scored 63 points in a single game. Basketball fans take sensational scoring performances for granted nowadays, but in almost all cases, the super games (like 100 points by Chamberlain or 72 by Baylor) are instances of a big man overpowering the opposition near the basket. But West, at 6-3, did it as a backcourtman. The more one contemplates the feat, the more impressive it becomes.

One of those who contemplates such things with heartfelt appreciation is Guerin. Richie’s own nine-year scoring total entitles him to 10th place on the all-time list for regular-season play, and in his position as a coach, he has to be cautious about public statements praising opposing players. But Richie was never one to mince words, and in his comments on West, he merely reflects the general NBA opinion, which cannot be twisted into disrespect for anyone.

“Until last year,” says Guerin, “I really thought there just wasn’t any question about who was greater, West or Robertson, and I’ll certainly never take anything away from Oscar. But West has really closed the gap.”

And there, perhaps, is the most-important point of all. Robertson, Russell, Chamberlain, Baylor—great as they are, they have been fundamentally at their peak from sophomore season on. No one has shown, each year, the distinct improvement that West continues to show. There’s no telling where he’ll stop—and that, come to think of it, is a characteristic of explosive forces, isn’t it?